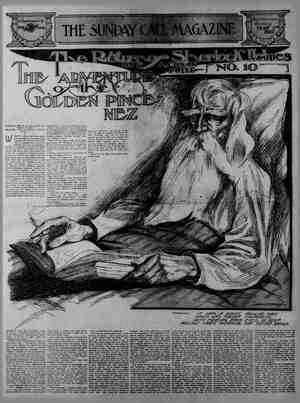

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, May 7, 1905, Page 9

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

T was a ginger cake and cider social at the h e of Limuel Jucklin. e Rainey had sung which, as it was whis- pered about, had come. out of a grand and the minister had told a story h might have come out of the ark, when Josh Dolittle remarked: “Uncle Lim, on several occasions we have heard u mention a feller named Shakes- I take it he lived a zood deal —was a circuit jedee, ke for you to tell e y n’ about him. bein’ as st have been one of the early set~ please do,” cried Dolittle's sister. ish girl who had begun to “re- * hy since the death of the ster's wife ld Limuel smiled. “Yes,” he said. “Shakespeare was an early settler. He was one of the earliest ones to settle hat the grandest thought€ of e strongest passions of the een set forth In words. are was a poet.” “You don't® say s replied Do- le, with his mouth remaining half en, as if it were not in good keeping se it S0 soon upon his own aston- sir, a poet,” said I . ‘And his next to the Bi , with his head turned slowly nodded and old n remarked: “W I didn’t Tell me about it a good deal of land. I reck- ed Jim Daggart, who held es on the domains of several Lim replied. ‘He owned re was—and all of the - s paid rent to him, ed in his territory.” wouldn't say that,” said the and Miss Dolittle remarked. I wouldn’t say that.” E profanely,” replied was a figure of speech. t a figure of speech may have truth in it, The universe is no greater than the human heart. And of the human ¥ Shakespeare was the confiden- As soon as a thought was in the world, he knéw ideas. He hundreds of people , but which had souls. He also to be e'future and said ’em. It y difference to him that he was livin' away back in the past. Why, for him, there wan't any past future. 'With Rim all was the 1 now.” 1, just think of that,” sald 2Ziss Dolittle, looking at the preacher. “Bet they sent him to the Legisla- ture every time he wanted to go,” de- clared Daggart. “Well, as to that I believe he did get to be a Justice of the Peace or some- thin’ of the sort” said Lim. “But money was as powerful then as it is now—the average man was just as S s short of-sight, ‘and wisdom’ cried out in the street and no man took heed.’ In this respect the world hasn't changed. Why, there were men that nobody has heard of since that time— men with a few thousands, with titles and ribbons tied about their shanks— men that wouldn’t have spoken to the poet if they had met him in the post- office, and a man that won't speak to you in the postoffice has got you down putty far underneath his contempt. The folks that saw Shakespeare every day didn't think he was great. The fact is that the oftener they saw him the less great he was. He built a play- house for the children of men and he wrote down things for the children to say, and the puffed-up chaps that come to the playhouse ‘lowed, “Well, ves, that will du putty well—for the sort.” They didn’'t know that the sort was for all time. Proud men were a-thunderin’ in the churches where there were gold candlesticks and books bound in silver and set with diamonds. But these proud and educated men didn’t know that the Lord’s inspiration had found its way to that playhouse where common folks stood up to lis- t The men that sat down were the And when they had heard they forgot, but the words spoken by the children of men that were playin’ re- mained in the minds and the hearts of the poor. Ah, and no man, that didn’t breathe his words upon the lowly heart has ever been great, They may have called him great, but he wasn’t. The greatest man is the one who has had the most-sympathy with man. The highest pinnacle that this world ever reached was when it lis- tened to the sermon on the’ mount. The roar of cannon may have meant human liberty. But the sermon on the mount meant human brotherhood, and brotherhood is the flower and the perfume of liberty.” “I reckon he'’s a talkin’ some now,” said Dolittle. “He's treed the thing sure enough,” declared Daggart. “Very worthily expressed,” said the RANCI THE SAN F “Now, don’t blaspheme,” Mrs. Benson. SCO_SUNDAY said old And turning to Jucklin she added: “I ain't forgot, Limuel, that I heard you cuss your steers one day.” “Yes, ma’am,” Lim replied; “and the man that could drive them steers with- out cussin’ ain’t got spirit enough in him to cast the shadow of immortality into the eternity of & jaybird. I'm a-talkin’ to you, ma’am. Them critters they ran away with me, ran through a thicket of’ wild plum bushes and tore me into shreds; and if I hadn’t cussed ‘em the Lord:would never. have for- given me.” ““Limuel,” sald his wife, miliate me any further, please. gbout your man that minister; and Miss Dolittle smiled-and - _in her smile might have been read the words, “Put your mind down on that ifvou can.” “But,” _observed the preacher, “Shakespeare wrote in most exalted style, He could not have been ad- dressing himself to the poor.” “‘His exultation of language was the raiment of the poor.” Lim. replied. “The wealthy didn't need the rich garb of his words. They had -silks woven in the hand loom. The velvets and the satins woven in the loom of a God-given imagination were too shad- owy for them. But out from among those shadows the poor in purse but the rich in fancy gathered his ward- robe and clothed himself. And every man that has been able to do this has been purpled like-an emperor.” “He keeps on a-travelin’,” said Do- little. ‘‘He's mendin’ his licks every min- it,” Daggart remarked. “Lim, we'll have you up a-preachin’ before long.” A TROUSSEAU By Heith Gordon (Copyright, 1904, by Keith Gordon.) ISS VAN ORDEN halted and regarded the display in the windows of Berg & Co. with kindling eyes. There really was no excuse for her to linger at that particular window, for Berg & Co., as everybody knows, are haberdashers, and Miss Van Orden was fatherless, brotherless and unmarried. “Talk about women's clothes,” ran her thoughts as she reluctantly pre- pared to move onward. “Why, there isn’t a window in town that compares with this for charm. Dresses—ugh! Ruffles, tucks, pleats, French knots and fussiness. But this—it's a poem! Just imagine some big creature in that pink bathrobe or’— With a silent laugh she caught her lip between her teeth and moved down the street toward the dry goods shops. But the windows appeared cheap, overloaded and tawdry. Berg’s store, with its display of masculine attire whose severity sometimes verged just near enough to softness and beauty to be fascinating, kept rising before her eyes, and almost automatically she re- traced her steps In that direction. By the time she again reached Berg & Co.’s she had an idea that made her giggle, though her eyes were bright and her cheeks went pink. Some girls, she refiected, hoarded china and sil- ver, others ilnen, and still others old mahogany against the day when “time and chance” ghould bring the man whom they all confidently expected. She would depart from such main- traveled ways and do something equally practical though more un- usual She entered the store rather timidly, but the sight of a portly dowager at one of the counters reassured her, and she was soon examining bathrobes with an ease and assurance that might have been acquired by years of shop- ping for masculine relatives. “What size?” asked the clerk when, after much hesitation betwen a pink and a blue one, she had finally decided on the former. At the question she stared at him in blank amazement. “That is, how tall is he?” he went on, judging from her look that she failed to under- stand. Then she recovered herself. “Six feet,” she answered, with a nonchalant, you-should-have-taken- that-for-granted air. And then, re- membering her preference in the mat- ter, she added, “‘and broad, very broad- shouldered, you know,” 4n a manner 80 deliberate and composed that with- out further question the clerk made out the check for “Mrs.” E. Van Or- den and solicitously begged her to look at their spring shirtings and the new- est cravats. “I don’t think he needs anything in that line just now,” she remarked with well assumed doubtfulness, as she lan- guidly viewed the stock. “Do they—would my husband have to be measured for these shirts?” she demanded. The clerk nodded. “But we'll send a,man up any time,” he explained with a polite desire to be accommodating. The lady shook her head. “You see that wouldn't do. He isn’t here—yet! But couldn’t I give you his collar measure and couldn’t you just make them proportionately?” The clerk thought they might, though they couldn’t guarantee the fit under those circumstances, and when his cus- tomer announced alrily that that MY B2l T77ZES 472 BB S 7752 RBocr wouldn’t make any difference he looked a trifle mystified. Eloise, meanwhile, emerged into the street aglow with the eagerness of a rather bored young -woman who has found a new and intesesting occupa- tion. Her grandmother Castle’s carved chest would be the very place to keep the things, and fortunately it stood in her room and had a good, strong lock. Her meditations were cut short by the salutation of & man who was pass- . ing, and whose glance carried some- thing that arrested her attention, It was something indescribable, elusiye— a quick, keen lighting up of his face at the sight of her, as instantly van- ishing in the calm, passive glance of a well-bred acquaintance. But she had seen {t—that strange, tefll-tale and her heart beat more quickly be- cause of it. . She had met him but twic -once at 2 dinner at Mrs. Lorimer} /and af- terward at the Bancker cotillion—but he was the cousin of her dearest friend: and she had heard more or less about “Philip” for years. ‘When at last the little flutter of the meeting had subsided, she remarked to herself demurely a certain coinci- dence—namely, that Philip Hamilton was six feet tall, very broad, shoulder- ed and that black hair and gray:eyes 80 well with pale pink, 5 Before her departure from town:for the summer, Eloise’s carved chest con- tained many treasures of ‘masculine wearing apparel. Among other things six shirts—it had taken her a fore- noon to select:them, and it had al- most been her undoing—had joined the pink bathrobe. 3 g It was really the “sws mono- gram on the sleeve that had convinced look, . her that she could not be happy until vagueness of ther orders. :Not even : - She rose as Phil} she added’them to his tmmtm,;u~ when she dreamily selected a pair of up the steps and “don’t hu- Talk could make IR LY ST o c!bihir outen shadows, but don't hu- she called it. She had decided every ‘detail—that on the pale gray one the monogram should be in dark red, on the tan in dark brown, etc,—when the clerk, who had learned to know her and whom she gulitily permitted ‘to address her as “Mrs. Van Orden,” paused, pencil suspended above his order book, as if waiting fc some further instructions, She regarded him in surprise. “That’s all,” she said at last. “But Mr. Van Orden’s initials—for the monogram, - yu know,” - he prompted smilingly. Eloise gasped. Never once had it occurred ‘to her that in order to have. that fascinating monogram on the left sleeve some initlals would be Te- quired. * The floor showed no disposition to open and swallow her up and the clerk was watching her as if he might tap his forehead significantly to hia fellow : clerks, once her back was turned, and shake his head sadly. What should she say? The possible man— ! “Oh, T. P. M.,” she flung out with hysterical relief as a thought occurred to her. 3 “T. P. M." the clerk repeated, ey- ing her reproachtully. " e “Right—er—they're not for Mr. Van Orden,” she observed firmly, giving <him laok for look. Z R Neckties and scarfpins were added to her collection without difficulty, but when it came to the purchass of dash and style, the question of size again croppediup. By thi ever, the clerk”had lea¥ned to think of her as the “eccentric” Mrs. Van Orden and was prepared for the lured her with its. miliate me.” ““All right, Susan, I beg your pardon.” “I think, myself,” said the minister, * stalls, waitin’ to be rf@ across the coun- “that you show to much more of ad- vantage when you talk on the—I might say, the subject of your favorite poet. It is then that you forget many of your, I might say—mannerisms.” “Yes, a man can talk best on the sub- Ject that interests him the most. But it would seem that everything has been said on Shakespeare that could be said, and yvet he ig still the most fruitful text that the mind of man can take up. I mean any text that applies to what we know and not what we speculate over. .He knew more about the body and guessed shrewder at the soul than any other men. His mind is an ocean with 50 many tides that it never grows stale.” 3 “But he's dead I take it,” said Do- little. . “Well, yes, he complimented death by dyin’. But he left his great ward- robe to all succeedin’ generations. Not R RRRRRNN RN, gray socks with dark red clocks, to match the gray shirt, and demanded them of a size to match a No. 16 col- lar, did he make any demur. The time for leaving town had ar- rived and the contents of the carved chest were carefully arranged for the last time and then locked up with the sweet-scented bags of lavender. Eloise sighed .at the thought of leaving the things, for they had come to have a sort of personality of their own. They were beautiful in them- ‘selves, and besides the one who was to wear them, should they ever be worn, would hy;’- for her the king of the world? She sometimes tried to picture him, but his face eluded her. Yet the face of her dream often bore a startling resemblance to Phillp Hamilton, and that gentleman himself was beco a more ard more prominent fact in her life. . ‘e More than once she had surprised a strange, tense question in his eyes— a speculative look that had made her happy, yet afrald. She half wished that she was not going to his cousin’s for the summer, since that would place them in the same little colony . for the next three months. But In the weeks that followed, ‘when riding, golf and moonlight even- . ings .on .the b ! _brough them constantly together, her feelings underwent a change' and she was ap- palled at the desolation she felt when he ran up-to town for a few days, as he did now and:then. It was on one of- these _ that she found herself alone on ‘porch one evening, when a brisk step sounded on the gravel. p Hamilton sprang came toward her =S B D, LA . T \ . only that, he gave ts humanity the key to his exhaustless corn-crib. He left unlocked. the “stable where: the swiftest steeds are standin’ In the try, over the mountain, up Into the clouds; and comin’ up over the hill right out yonder is the moon, his moon, that he spoke about so often. He made it tenderer for you and me. And the man that makes the moon brighter and tenderer makes the road to heaven easier.” . ' “Must have had a big funeral,” spoke up Abner Howerson, the neighborhood undertaker. - “Yes,” Lim replied. “The procession started nearly three hundred years ago and the tail end of it isn't'In sight yet. And the descendants 'of men that wouldn't have spoken to ‘him:in the postoffice would now give their wealth for & handful of the straw he slept on. But yoy can’t blame man. He was born blind and sometimes his eyes are never opened.” (Copyrighted, 1905, by Opie Read.) NSSOSSSONSNSNOEINE) in the soft moonlight, the tumultuous Joy that she supposed hidden in her heart shining in her eyes and dancing on her lips. & He looked down at her for one mo- ment with eyes before whose mastery her own wavered and fell.” Then, with a low, contented ‘laugh, he drew her to him, whispering, “There’are some things, my darling, that one does not need to ask.” S It was one rainy evening soon after the return from thelr wedding trip that Bloise told her husband the story. of the trousseau it had amused her to provide—a tale that he listened to with gusts of laughter. . “Oh, my; oh, my!" he groaned as she held up the articles one after an- other. “You certainly have good taste, though, little girl,” he added approvingly, “and I hope they'll fit!™ Then his face sobered, and he stared at' the monogram on a shirt-sleeve fixedly for a second, and then looked up at her with puzzled eyes, while she watched him furtively, wishing that she could get that ridiculous, effemi- nate bathrobe out of sight without his catching & glimpse of 1t.§" * “T. P. M.,” he sald slowly. The words sounded Ilke water dropping SPm’ walting for you to explain,™ he said coldly.™ v Eloise made ® little rush at him and hid her face on his shoulder. "Don't you see,” P A great light broks over Phillp's face, and as a‘penalty for the momen- tary clouding of his faith, he. wore the silk-lined bathrobe like a martyr.