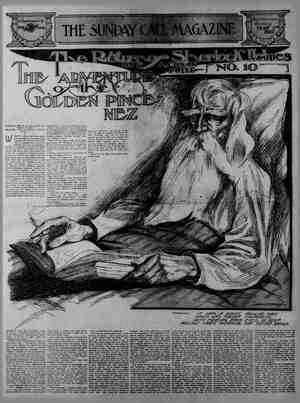

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, May 7, 1905, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

"—'_ - D emm— . N e SO e to Gordon in London. The clergyman, d in Pisa, asked the use of nd floor of the Lanfranchi e understood it was unoccu-~ n which to hold service on the g Sunday. the smart of his sorrow the wraith of a satiric smile touched Gor- don’s lips. He, the unelect ahd unre- e, to furnish a tabernacle for orthodoxy? The last sermon he had was one preached by a Lon- don divine and printed in an English magazine; its text was his drama.of >ain and it held him up to the as & denaturalized being, who, having drained the of sensual sin to its bitterest’ dregs, was resolved in k ypse of blasphemy to show 2 unconcerned fiend. And vet, after all, the request was natural enough. The palace that housed was the most magnificent in Pisa, almost a castle. And, n ‘e lower floorwas empty and un- . Was he to mar this saner exist- in which he felt waking those G inspirations and ideals, with the ude spirit of combativeness, in which s bruised pride took refuge when I r clamor thrust him from his i If he refiised would not the very refusal be made a further Wweapon against him? Had Gordon seen the mottled clerical countepance that waited for answer in the street below he might have read a partial answer to this question. Cassidy’s ship having anchored at Leghorn, he had embraced the oppor- tunity to distribute a few doctrinal tracts among the English residents of this near cathedral town. Of Gordon's lite in Pisa he heard before he left the ship. In the Rev. Dr. Nott he had found an accidental traveling compan- jon with an eve single to the glory of the Established Church, who was even then bemoaning the lack of spiritual advantages in the town to which he was bound. His zealous soul rejoiced in the acquaintance and fostered it on val. The idea of Sabbath service in ]ish had been the clergyman’s; that of the Lanfranchi Palace as a place wherein to gather the elect' had been Cassidy’s. The suggestion was not without a certain genius. To the doc- tor’s uplifted hands he had remarked with unction that to ask could do no the request, even if refused, e precious seed sown. Cassidy presaged refusal, which should text and material for future dis- of his own. ng at the Ca. Lanfranchi entrance sermon of which he self years before at perched upon a ta- had never forgotten it. He his lips with his tongue at the ought that he who had then saster of the abbey—host of that ewstead ble. He touched egious ridicule in Lo —was now spurned of the righteous. at that hour had no thought dy, whom he had not seen in messenger that Mr. very welcome to the use of the was the answer he gave the moment later Teresa and Count Pletro Gamba re-entered. Teresa’s eves were wet and shining. Her brother's face was calm. He game frankly to Gordon and held out his hand. While the two men clasped hands the naval surgeon was ruminating in chagrin. Gordon’s ‘courteous assent ave him anything but satisfaction. He took it to Dr. Nott's lodgings. As Cassidy set foot In the street again he stopped suddenly and unaec- countably. - At the Lanfranchi portal in the dusk he had had a view of a swarthy face that roused a persistent, baffiing memory. The unanticipated reply to the message he had carried had jarregd the puzzle from his mind. It recurred again now, and with a sud- den stab of recollection. His teeth shut together with a snap. He lay awake half that night. At sunup he was on his way back to Leg- horn, with a piece of news for the com- mander of the Pylades. CHAPTER LI Dr. Nott’s Sermon. It was a thirsty afternoon. Teresa and Mary Shelley—the latter, bonneted and gloved—sat at an upper window of the palace, watching through the Vene- tian blinds the English residents of Pisa approaching by twos and threes the entrance below them. Dr. Nott's service had been well ad- vertised, and a pardonable curiosity to gain a view, however limited, of the palace’s interior, swelled the numbers. Besides this, one of the Lanfranchi servants had had an unlucky fracas with & police sergeant which, within e few hours of its occurrence, rumor had swollen to a formidable and bloody affray: Gordon had mortally wounded two police dragoons and taken refuge in his house, guarded by bulldogs; he had been captured after a desperate re- sistance; forty brace of pistols had been found in the palace. These tales had been soon exploded, but the affair nevertheless possessed an interest on this Sunday afternoon. The palr at the window conversed on various topics: Pietro, the new meém- ber of the household, and his rescue in Lake Geneva, of which Mary bad told Teresa; Prince Mavrocordato, . his patron, exiled from ‘Wallachia, and watching eagerly the plans of the primates, now shaping to revolution, in Greece, his native country; Shelley’s new sail-boat, the Ariel, anchored at the riverbank, a stone's throw from where they sat. As they talked they could hear from the adjoining study Gordon's voice reading aloud and the sharp, eager, explosive tones of Shelley es he commented or admired. Both watchers at length fell silent. The sight of the people below, soberly frocked and coated, so unmistakably British in habiliment and W@emeanor, had brought pensive thoughts to Mary Shelley of the England and Sabbaths of her girlhood. Teresa was thinking of Gordon. Since the hour he had learned that melancholy news from Bagnacavallo he had not spoken of Allegra, but there had been a look In his face that told how sharply the blow. had plerced. If there had been a lurking jealousy of his past in which she had no part, it had vanished forever when he had said, with that patient pathos that wrung her heart: “I understand.” The words then had roused in her some- thing even deeper than the maternal. instinct that had budded when she tock him wounded to Casa Guiccloli, deeper than the utter joy with which she had felt his arms fas they rode through the night from the villa where he had waked her from that deathlike coma. It was a sense of more intimate comprehension to which her whole be- ing had vibrated ever since. Not but that she was consclous of struggles in him that she did, not fully grasp. But to-day, as she sat silent by the window, her heart was saying: “His old life is gone—gone! I belong to his new life. I will love him so-that he will forget! We shall live always ‘in Italy together, and :he will write poems that the whole world will read. and some day it will know him as I do!” The sound of a slow hymn rose from the floor below, and Tergsa’s companion stole to the hall where the words came clearly up the marble staircase: £ O spirit of the living God, In all Thy plenitude of grace, Where'er the foot of man hath trod, Descend on our apostate race. As Mary listened, Teresa came and stood beside her. Convent bred, re- ligion to her had meant churchings, candled processionals and adorations before the crucifix which hung always above her bed. Her mind dirdet, im- aginative, yet with a natural freedom from traditional constraint, suffered for the home-nurtured ceremony left behind in her flight with Gordon. But her new experience retained a sense of devotion deeper because more primi- tive and instinctive than these: a mys- tic leaning out toward good intelli- gences all about her—the pure longing with which she had framed the prayer for Gordon eo long ago. She listened eagerly now, not only because of the priestly suggestion in the sound, but also from a thought that the ceremony below had been a part of his England. This was in her mind as a weighty voice intoned the opening sentences, to drop presently to the recitation of the collect for the day. While thus absorbed Gordon and Shelley came and leaned with them at the top of the stair. The congregation was responding now to the litany: “From all blindness of heart; from pride. vainglory and hypocrisy; from envy, hatred and malice and all un- charitableness, “Good Lord, deliver us.” & It was not alone Mary Shelley to whom memories were hastening. The chant recalled to Gordon, with a singu- lar, minute distinctiness, the 'dreary hours in the Milbanke pew in the old church at Seaham, where he had pass- ed that “treacle-moon” with Annabel. Blindness -of heart, hatred, uncharita- bleness; he had known all thése. “From lightning and tempest—" One phase of his life was lifting be- fore him startlingly clear: the phase that confounded the precept with the practice and resented hypocrisy by a wholesale railing at dogma—the sneer with which the philsgophic Roman shrugged at the Galilean altars.;” The ancient speculation had. fallen in_the wreck at Venice—to risg.one sodden dawn in the La Mira forest. The dis- carded images had re-arisen then, but with new outlines. They still framed skepticism, but it was desponding, not scoffing—a hopelessnesé whose . climax was reached in his soul’s; bitter cry to Padre Scmalian at San Lazarro: “Ifjit were only true!” Since, he had learned the supreme awakening of love which had already aroused his conscienee, and now in its development, that iove, lighting and warming his whole fleld made him con- hitherto of human sympathy, scious of appetences guessed. “That it may please thee to forgive our enemies, persccutors and slandef- ers, and turn cheir hearts; p; “We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.” Gordon frowned. The chant died ‘while the visitors gaid their adleus. The feeling of es- trangement had been deepening in Shelley’s fair-haired wife. For a mo- ment she had been back in old St. Giles’-in-the-Fields, whither she had gone so often of a Sunday from Wil- liam Godwin's musty book shop. She put_her-hand on Shelley’'s arm. “Bysshe,”” she whispered, “let us stop a while as we go down, It seems SO like old times. We can slip’'in at the back and leaye before the rest. Will you?” Shelley looked ruefully at his loose nankeen trousers, his jacket sleeves worn from handling the tiller, and ghook his tangled hair, but seeing her wistful expression, acquiesced. “Very well, Mary,” he said; ‘“‘come along.” He followed her, shrugging his shoulders. At the entrance of the impromptu audience room, Mary drew back uncer- tainly. The benches had been so dis- posed that the late comers found thém- selves fronting the side of the audience and the center of curious eyes. Shelley colored at the scrutiny, but it was too late to retire, and they seated them- selves in the rear. At the moment of their entry the Rev. Dr. Nott, in cassock and sur- plice, having laid off the priest (he was an exact high-churchman) was kissing the center of the preacher's stole, He settled the garment on his ghoulders with satisfaction. He had been annoyed at the disappearance of Cassidy, on whose aid he had counted for many preliminary details, but the presence of the author of “Queen Mab” more than compensated. This would indeed be good seed sown. He pro- ceeded with zeal to the text of his sermon: “Ye are of your father, the devil, and the lusts of your father ye will do.” A flutter winged among the benches and the blood flew to Marv's cheek asg he doled the words a second time. 3 ‘With his stay in the town, the clergy- man’s concern had grown at the tolera- tion with whieh it regarded the pres- ence of this reprobated apostle of heli- ish unbellef. The thought had been strong in his mind as he wrote his ser- mon. This was an opportunity to sound the alarm of faith. His face shone with ardor. The doctor vossessed a vocabulary. His volce was.sonorous, his vestments above reproach. He was under the very roof of Asteroth, with the visible pres- ence of anti-Christ before his eyes. The situation was inspiratory. From a brief judicial arraignment of skeptic- ism, he launched into allusions unmis- takably, personal, beneath which Mary Shelley sat quivering with resentment, her softer sentiment of - lang syne turned to bitter regret. Furtive glances were upon the pair; Pisa—the English part of it—was enjoylng & new sensa- tion. - A pained, flushing wonder was in Shelley’s diffident, bright eyes as the clergyman, with outstretched arm, thundered toward: them the warning of Paul: “Beware lest any man spoil you through philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, after the rudiments of the world! Their throat is an open sepulchér; ‘the poison of akps is under their lips.” Mary's hand had found her hus- band’s. “Let us go,” he said in an un- dertone, and drewiher to her feet. They un- neither smiled now nor passed to the door, the cynosure of ob-- servation, the launched utterance pur- suing them: “Whose mouth is full of cursing and bitterness, and the way of peace have they not known.” ¢ In the t Mary" t: him. Y d, Bysshe,” she- alf smiled, but his eyes were feverishly bright. He kissed answered: “I'm going for a sail. Don’t worry if I'm not back to-night. I'll run up to Vud Reggia. "he wind will do me good.” He crossei the pavement bareheaded and leaped into his sailboat. A mo- ment later, from the bridge, she saw through eclouding tears the light craft careening lown the Arno toward the sea. . The agitatrd ripple of the audience that followed their exit was not yet stilled when the discourse was strange- ly interrupted- From \the glvemcnt g came the siand of running® feet, a hoarse shout and a shot, ringing out sharply cn the Sabbath stillness. A 'mecond later a man dashed panc- ing into the outer hall with a British marine at his beels. . CHAPTER LIL Trevanion in the Toils. In sending Trevanion that day to the barracks on the Lung' Arno—whose door Cassidy had once seen him enter and in whose vicinity- the naval sur- geon, following this clue, had posted his squad of tars—luck had fallen oddly, The coursed hare has small choice of burrow. The Lanfranchi entrance was the q ¥y's only loophole and he took it. & As the hunted man sprang across the threshold he snatched the great iron key #om the lock and swung it on the heéad of his pursuer. The marine drop] with a cut forehead., falling full in the doorway of the room where the service was in progress. Instantly the gathering was in con- fusion. The . sermon ceased, women screamed and their escorts poured into the hall to meet Cassidy, entering from the street, flushed and exultant, with a half-dozen more bluejackets. - 'His foremost pursuer fallen, Trevan. ion leaped like a stag for the stalr. But half-way up he stopped at sight of a figure from whom he could hopbe no grace. Gordon had heard the signal- shot, armed himself and hastened to the stairway. 5 For once in his life Cassidy was obli- vious of things religious. He had for- got the afternoon’s service. = He scarce- ly saw Dr. Nott’s hprror-lifted hands as his cassock _fluttered between frightened worshipers to the door. His look did not travel to Gordon or be- yond, where Teresa's agitated face watched palely. His round, peering €yes fastened with malfgnant triumph on the lowering figure midway of the marble ascent. “Now, my fine ensign,” he said with exultation, “what have you to say to a trip to the Pylades?” Trevanion’'s dark face whitened. But his hand still gripped the key. “I had enough of your cursed ship!" he flung in surly deflance, “gnd vou'll not take me, either.” Cassidy laughed and turnéd to the seamen st his back. They stepped for- -ward. s >'s mind, in that moment of ucial forces were weirdly Cver the heads of the v, through the open door, he saw 2 ship’s Jolly-boat, pulling along the Aino bank, Leghorn—the Pylades —and years in a military fortress. That was what it meapt to Trevanion. And what for him? The 'peace he coveted, a respite of persgcution, for him and for Teresa—the right.to live and work unmolested. It was ‘a lawless act—selzure unwar- . ranted and on a foreign Soil: an at- tempt daring but not courageous—they were ten ‘agalnst one. It was a déed: of ‘personal and private revenge gn, the . part of - ;And the man’ 5 taken' re er his roof. For other he sheer sensé of Justice and hatred of . hypoerisy. ‘But:‘for him—a poltroon, a& skulker, and—his enemy? G What right had he to inter Te? fi The manner was high-handed, but the penalty owed to British Just. It was not his affair. . The hou: he had sat in the moonlight near the Ravenna osteria, when his conscience had accepted this Nemesis, he had put away the temptation to harm - him; though the other's weapon had struck, he had lifted no hand. He had left all to fate. And fate was arranging now. He had not summoned those marines! But through these strident volces sounded a clearer one in his soul. It was not for that long-buried shame and cowardice in Greece—not for the attempting on his life in Bagnacavallo nor for anything belonging to the pres- ent—that Trevanion stood now in this plight. It was ostensibly for an act antedating either, one he himself had known and mentally condoned years ago—a boy’'s desertion from a hateful routine. ' If he let him be taken now, was he not a party to Cassidy's re- venge? Would he be any better than Cassidy? Would it be in him alse any less than an ignoble and personal re- taliation—what he had promised him- self, ‘come what might, he would not seek? He strode down the stair, past Tre- vanion, and faced the advancing ma- rines. “Pardon he,” he sald. “This man is in my house. By what right do ypu pursue him?” it The bluejackets stopped. A blotch of red sprang in Cassidy’s straw-col- ored cheeks.. “He is a deserter.from a king’s ship. The marines are under orders. Hinder them at your:'peril!” “This is Italy, not the high seas,” rejolned Gordon, calmly. “British law does not_reaclr here. You may say that'to the captain of the Pylades.” ... Cassidy turned furiously to his men. Go on and take him!” he commanded. 103:‘:1!“: fih:zt agvagced. ?ut they ed full ‘intc Gordon’s pistol, the voice behind it safd: E i - "‘Thoat, ‘under thdla roof, no man ghall 0! n my word as a peer o land!” i o5 By A few moments later Cassidy, his face purpled with disappointment, had led his marines Into the street, the agitated clefgyman had gathered his fiock again, and the hall was clear. A postern gate opened from the Lanfranchi garden, and to this Gordon led Trevanion without a ward. The latter passed out with eyes that did no}u mao: :u- cel‘livebf:ir& rdon clim the stairway to where Teresa waited, shaken wm'z’the occurrence, the Rev. Dr. Nott was rounding the services so abruptly ter- lmi.nupfl with the shorter benpdiction: “ ““The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellow- ship of the Holy Ghost be with ‘us all evermore. ' Amen.” i e R CHAPTER LIIL - The Coming of Dallas. e was S ng ‘in study, its - windows thrown open to the - air, the blinds drawn g less sun that beat ho m the sl Arno and loaded the world: wi trees in ed and: chant In the hed n the pars| : o1 from the dQusty street-came the the garden , old sneer become praise—now? sisid; : ng;rnva' interposed from & - dmiralty was THE SAN FRANCISCO SUNDAY CALL of a procession of religiosi, bearing relics and praying for rain. The man who sat by the table wore the same kindly, scholarly face that Gordon hgd known of old, though his soft white hair was sparer at the temples. To make n%;, urney he had spent the last of a check he {ul once recéiveq for £600. His faith in Gordon had never wavered. Now, as he looked at the figure standing opposite, clad in white waistcoat and an hussar braided Mkfit of the Gordon plaid, young and lithe, though with brown Tocks grayed, and with eyes brilliantly haunting and full of a purpose they had never before 1, his own gaze misted with hope and wm{ul- ness. He had had an especial object in this long journey to Italy.: ‘‘Hobhouse is still with his regi- ment,” he proceeded. ‘“He'll be in Parliament ore Jong. We dined to- gether just a month ago to-night at ‘White’s Club. Lord Petersham is the leader of the dandies now. Brummell left England for debt.” 4 In that hour's conyersation Gordon had ee%n faded pictures fearfully dis- tinct. He seemed to be standin in in his old lodgings in St. Jame: et.. —a red carnation in his buttonhole— facing Beau Brummell and Sheridan. He rememberéd how he had.onte let the old wit down .in his cocked hat at Brookes'-—as he had long ago been let down into his grave! He gmiled painfully while He said with slowness:- “Three great men ruined in one year: Bonaparte, Brummell and I A king, a cad and a castaway!” His eyes were fixed on the empty fireplace. as he spoke, but what they saw was very far uwg. 5 “How is Murray?” he asked pres- ently. b “I visited him a fortnight before I left. He had just Publlnhed the first part of ‘Don‘Juan” Gordon winced. “Well?” he asked. ““He put only the printer’s' name on the title page. The day it appeared he went to the country and shut him- self up. He had not even dared open his letters.” Sk “I can’t -blame him" — Gordon's voice was metallic—"Moore wrote me the Attorney General would probably suppress it.” “1 carried him the reviews,” con- tinued Dallas. - - “I can guess their verdict!™ e The other shook his head with an eager smile that brightened. his whole countenance, “A few condemned; of course. Many hedged. But the Edin- burgh Review—"" % “Jeffrey. What did he say?” The answer came with a vibrant emphasis: “Thdt - every word was touched with immortality!” Gordon. turned, surprised into won- der. His ancient detr,amoi whose early blow had struck from the “fiint in his soul that youthful flash, his dynamic - Satire. e literary Nero whose nod had killed Keats, Wanlthe m- mortality—not “damned to everlasting fame?’ A glow of color came to his face. The oldéer man got up hastily and laid his hand affectionately on the other’s shoulder. It seemed the mo- ment to®say what was on his mind. His voice shook: “'George, come back to England! Do not _exile yourself longer. It is ready to. forget its madness and to regret. Public feeling has changed! When roline Lamb published ‘Glen- :wr novel that made ‘you'out nster, it did not.sell an ' appeargd ‘at: Lady - Jer- asquerade as Don Juan in the of a Mephistopheles;; and the ven hissed. don is‘waiting , George! AI%%&M You once yours again. | ¥ou have only - back!” ; but at Lady C: 4rvon, T shi to. 5 last, the purport of s journey. . Gordan felt ‘his muscles grow rigid. {The meaning of other things: Dallas T had told—gossip of society and the clubs—wag become apparent. Could ‘the ‘tide have turned, then? Could it be that the !(me had come when his presence could reverse the popular ver- dict, cover old infamy and quench in renewed reputation the poisoned enmity that had poured desolation on his path? The fawning populace that had made of his domestic life only a shredded remnant, hounded him to the wilds and entombed him in black infamy— did it think now to re-establish the dis- honored idol on its pedestal? For an instant the undiked memory of all he had undergone swept over him in a stifling wave. The months of self- control faded. The new man that had been born in the forest of La Mira fell away. The old rage roge to clutch at his throat—the fiery, ruthless deflance that had lashed his enemies:in Al- mack’s Assembly Rooms. It drove the color from his face and lent flame to his eyes as he answered hoarsely: “No! Never—never again! It is over forever. When I wrote then. it was not for the -world’s pleasure or pride. I wrote from the fullness of my mind, from passion, from impulse. And since 1 would not flatter their opiniofis, they drove me out—the shilling scribblers and scoundrels of priests, who do more harm than all the infidels who ever for- got their catechisms, and who. if the Christ they profess to worshin reap- peared, would again crucify him! Since then I have fed the lamp burning in ' my brain with tears from my eyes and with blood from my heart. 1t shall burn on without them to the end!” His old tutor'’s hand had dropped from his shoulder. Dallas was crest- fallen and disconcefted. He turned away to the window and looked out ~gadly over the Arno, where a ship's launch floated by with band instru- ments playing. » For Gordon the rage passed as quick- ly as it had come. The stubborn demon that had gnashed at its fetters fell back. A feeling of shame suddenly possessed him. “Scoundrels of priests!” He thought of Padre Somalian with a swift sense of confrition that his most reckless phraseology had never roused in the old days. Standing there, regaining his tem- perate control, a sound familiar, yet long unheard, floated in from out of doors. It was a strain belonging to the past that had come so sharply home to him—the sound of the music on the launch in the river playing “God Save the King.” He approached the window and touched the man who looked out. “Dallas!"” he said. “—Dallas!” The other turned. His eyes were moist. - He saw the alteration in Gor- don’s mood. ‘ “George,” he urged huskily, “do you one llas meant—=so: not seen! Gordon’s “ to the river, flowing lead with an ofly scum ur chart that, wll::thct ol swittly rising to paint ou ing track of the sun.. The laun 'm:::l::tk c:um Bven -1t all Dallas ” Go back—and Ada's sake, who would live to bear his name, to return to an empty reinstate- ment and stifle with th¢ pulpy ashes of dead fires this love that warmed his new life! For Ada's sake—go back, and leave Teresa? [ The visitor spoke again. ‘When he had asked that question a child, not a woman, had been ih his thought. He had not told all he had come to say. “I have been to Seaham, George; I went to Lady Noel's funeral.” His hearer started. “You saw Ada?" he asked, his features whitening. “You saw her?” He clutched Dallas’ wrist. “She is six years old. Did she speak my name, Dallas? What do they teach her of me?" The other's tone was almost as strained; the story he had to tell was a hard one. *“Your portrait, the large one painted the year you were married, hung above the mantelpiece. It was covered with a heavy curtain. Lady Noel's will for- bade that the child should see it before her twentieth year. Laddie, Ada has never heard your name!” Dallas stopped abruptly at the look on. Gordon's face, No anger showed there, only the dull gray of mortal hurt. A curious moaning sound had arisen, forerunner of the sultry tem- pest that had been gathering, rapid as anger. The cicalas had ceased shrilling rom the garden. A peculiar warm lampness was in the air and a drop of rain splashed on the marble sill. “Do you wonder,” Dallas continued after a pause, “that I want you to go back?"” Gordon made no reply. His eyes ‘were focused on a purple stain of stérm mounting to the zenith, like some caryatid upholding a caldron of steam, all ink and cloud color, while before™ it slaty masses of vapor fled like monstrous behemoths, quirted into some gigantic sky-inclosure. <. Dallas pulled the ‘window shut. “With the action, unheralded as doom, a great violet sword of lightning wrote the autcgraph of God across the sky, and a shock of thunder, instantaneous and;crashing like near ordnance, shook the walls of the palace. It loosed the vicious pandemonium of the tropic air into tornado, sudden and appalling. ‘While the echoes of that detonation stfll ‘reverberated into the room, as though hurled from the wing of the unleashed wind, came Mary Shelley, drenched with the rain, bareheaded, “Shelley's boat has not returned!” she 'walled. “He is at sea in the storm. Oh; I am afraid—afraid—arraid!” Teresa entered at the moment with a frightened face, loose-haired and pale, and Mary ran to her, sobbing. Gordon had turned from the window, but his countenance was void and ex- pressionless. “‘Shelley?” he repeated vacantly, and sat down heavily in the nsarest chair. Teresa suddenly put the arms of the yeeping girl aside and ran to him. - “Gordon!" she cried, as Dallas hur- ried forward in alarm. *Gordon, what is it?" pe “England—Teresa—"" he said. his head fell forward against breast., For twelve hours, while the wild, typhoon-like storm raved and shrieked er Pisa, Gordon 'lay seemingly in a deep sleep. He did not wake till the next dawn was breaking, wetly bright and cool. When he woke it was to healthful life, without recollection of pain or vision. And yet in those hours intervening, strange things happened hundreds of leagues away in England. . Has genius, that epilepsy of the soul, a shackled self, which under rare stress can leave the flesh for a pilgrimage whose memory is afterward hidden in that clouded abyss that lies between its waking and its dreaming? Did some subtle telepathy exist between his soul in Italy and the soul that he had transmitted to his child? Who can tell? But that same afternoon. while one George Gordon lay moveless in the Lanfranchi library, another George Gordon wrote his name in the visitor's book at the king’'s palace, in Hyde Park, London. Lady Caroline Lamb, from her carriage seat, saw him en- tering Palace Yard and took the news to Melbourne House. The next morn- ing’s papers were full of his return. That night, too, she who had once been Annabel Milbanke woke unac- countably in her room at Seaham. In the county of Durham. to find the trundle-bed in which her litfle daugh- ter Ada slept, empty. She roused a servant and searched. In the drawing-room a late candle burn- ed, and here, in her night-gown. the wee wanderer was found. tearless. wide-awake and unafraid. gazing steadfastly above the mantel-piece. The mother looked and cried out. The curtain had fallen from its fasteninzs. and the child was looking at her father’s portrait. CHAPTER LIV, The Pyre. Over the hillocks, under the robed boughs of the Pisan forest. went a barouche, drawn by four post-horses ready to drop from the intensity of the noonday sun. In it were Gordon and Dallas. They had been strangely silent during this ride. From. time to time Dallas wiped his forehead and mur- mured of the heat. Gordon answered in_monosyllables. “ They had reached a lonely stretch of beach-wilderness, broken by tufts of underwood, gnawed by tempests and stunted by the barren soil. Before it curved the blue windless Mediterran- ean, cradling the Isle of Elba. Behind. the view was bounded by the Itallan Alps, volcanic crags of white marble, ‘white and sulphury like a frozen hurri- cane. Across the sandy extent. at equal distances, rose high, square bat- tlemented towers, guarding the coast from smugglers. Gordon’s gaze, though it was fixed on the spot they were a| saw only a womsan’s desolated form clasped in Teresa's sympathizing arms. At a spot marked by the with- ered trunk of a fir tree. near a ramshackle hut covered with a flimsy - shelter for —the "~ vehicle stopped and _Gor- don descended. A little way off was pitched a tent, by which stood a group of mounted dragoons and Ital- Then her lan laborers, the latter with mattocks was tunkempt and unshaven, his swarthy face clay-pale, his black eyes bloodshot. He had searched the coast day and night, sleepless and savage. There had been - desperation in his toil. In his semi-barbaric blood had raged a curious conflict between his hatred of Gordon and something roused by the,other’s act in delivering him from Cassidy’s marines. He was by instinct an Oriental, and instinct led him to revenge; but his strain of ‘Welsh bloéd made enemy’s mag- nanimity unforgetable“and had driven him to this flerce effort for an imper- sonal requital. Because Shelley had been the friend of the man he hated but who had aided him, the deed in some measure satisfied the crude re- morse that fought with his vulpine enmity. Almost touching the creeping lip of .surf, three, wands stood upright in the sand. Trevanion beckoned the labor- ers and they began to dig in silence. At length & hollow sound followed the thrust of a mattock. Gordon drew nearer. He heard lead- enly the muttered conversation of the workmen as they walited, leaning on their spades—saw but dimly the uni- forms of .the dragoons. He scarcely felt the hot sand scorching his feet. Was the object they had unearthed that whimsical youtk whom he had seen first in the Fleet Prison? The unvarying friend who had searched him out at San Lazzarro—true-heart- ed, saddened but not resentful for the world's contumely, his gaze unwaver- ing from that empyrean in which swam his lustrous ideals? This bat- tered flotsam of the tempest—could this be Shelley? From the pocket of the faded blue Jacket a book protruded. He stooped and drew'it out. It was the “Oedi- pus” of .Sophocles, doubled open. Aldoneus! Aldoneus, I tmplore Grant thou the stranger wend his way To that dim land that houses all the dead, With no long agony or voice of woe For eo, though many evils undeserved Upon his life have fallen, God, the All-Just, shall raise him up again! He lifted his eyes from the page as Trevanion spoke his name. He fol- lowed him to the tent. Beside it the laborers had heaped a great mass of driftwood and fagots gathered from a stunted pine growth. Shuffling footseps-fell behind him— he knew they were bearing the body. He averted his eyes, smelling the pun- gent, aromatic odors of the frankin- cense, wine and salt that were poured over all. Trevanion came from the tent with a torch and put it into his hands. Gor- don’s. fingers shook as he held it to the fagots, but he did the work thor- oughly, lighting all four corners. Then he flung the torch into the sea, climbed the slope of a dgne and sat down, feeling for an Iinstant a giddi- ness, half of the sun’s heat and half of pure horror. The flames had leaped up over the whole pyre, glistening with wavy yel- low and deep indigo, as though giving to the atmosphere the glassy essence of vitality itself. Save for their rustle and the shrill scream of a solitary curlew, wheeling in narrow fearless circles about the fiery altar, there was no sound. Sitting apart on the yellow sand, his eyes on the flame quivering up- ward like an offering of orisons and aspirations, tremulous apd radiant, the refrain of-Ariel came to Gorden: Of his bones are coral made: Thosé are pearls, that were his eyes; Ncth.ng of him that doth fade. But doth suffer a sea-change Into something rich and strange. Had Shelley been right? Was death, for Christian or pagan, only a part of the inwoven design; glad or sad, om that veil which hides from us some high reality? Was Dallas—was Padre Somalian—nearer right than his own questioning that had ended in nega- tion? ‘Had Sheridan found the girl wife he. longed for—beyond the ques- tioning and the stars? And was that serene soul, whose body now sifted to its- primal elements, walking free somewhere in a universe of loving in- telligence which to him, George Gor- don, had been at most only “The Great Mechanism ?” At length he rose. The group in the lee of the tent had approached the pyre. He heard wondering exclama- tions. Golng nearer, he saw that of Shelley’s body there remained only a heap of white ashes—and the heart. This the flames had refused to touch. He felt a strange sensation dart through every nerve. Trevanion thrust, in his hand and took it from the enibers. Gordon turned to the barouche, where Dallas leaned back watching, pale and grave. He had brought an oaken box from Pisa, and returning with this to the beach he gathered in it the wine-soaked ashes and laid the heart upon them. His pulses wers thrilling and leaping to a wild man- hysteria. As h-hnphmd the coffer in the carriage he saw 'l'tvv‘l-lflsn wading knee deep In the cool surf. “He settled the box between his knees and the horses toiled laboriously toward the homeward road. A sounq presently rose behind them. It was Trevanion, shouting at the cur- lew circling above his head—a wild, savage scream of laughter. Gordon clenched. his hands on the edge of the seat and a great tearless sob broke from his breast. It was the release of the tense bowstring—the scattering of all the bottled grief and horror that possessed him. He became aware after a time that ter had p! of the “Oedipus” and was translating. As he listened to the flowing lines, a mystical change was wrought George Gordon. With a ac- curacy of estimation, his mind set the restless cravings of his own past over against Shelley’s placid temperament —his long battle beside the other’s ac- quiescepce. He had been the simoon, elley the trade wind. He had razed, Shelley had reconstructed. His own doubts had pointed him—where? Shelley had been meditating on im- moi ity when he met the end. end? Or was it only the be- 7 “God, All Just, shall raise him up again!”—the phrase was running in his mind tered the that Fletcher handed him a card in the re-en- gentleman came with hh: Mavrocordato,” he said. “They wish in -moumnmmmvm return - ‘The card read: