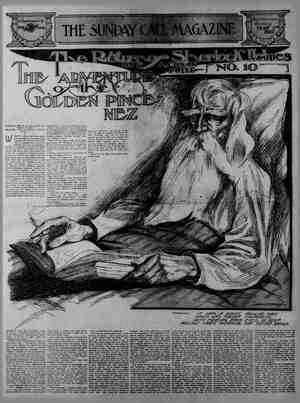

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, May 7, 1905, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

PROF-J-J- -THE ' SAN FRANCISCO SUNDAY CALL. ONTSOAERY T]-[E PERSONALITY QF THE NAN---2Y HELEN DARE- REMEMBER when I was a little child in Yuba City—it was when I was about five years old— watching with delight the pass- age of clouds acrosy’ the sky and seeing those clouds Tresting, as it were, on the mountain tops. I asked to be taken to the moun- tops, because I thought that fif Iy I could get there I could take hoid of the clouds and fly; that I could grasp them and they would carry me with them. I think my interest in aerial navigation dates back to that time.” And to-day the little child, grown to a manhood with which much of the child remains, hes given to man the wings of a bird, has solved the most fascinating problem in the world, the problem of fiying. Man need be no longer an earth- creeping, earth-keeping thing, envying the birds of the air. He, may cleave the blue and be no longer at the mercy of the air currents to be ‘wafted hither and thither like a bit of wvagrant thistledown; he can fly in the teeth of the wind, across the wind and with the wind, as he pleases, thanks to Professor Montgomery—thanks to that little child of long ago, whose wonder- too, ing eyes looked out across the dark- ling Californian canyons, whose poetic faney leaped to grasp the fleecy clouds that paused upon the mountain tops and go with them on their limit- less flights. From childhood's radiant dream to manhood's realization there's been” & long, bard road to travel—the straight, hot, dusty road of patient endeavor, paved with error, failure, discourage- ment, the long, long road of detail conquered step by step, traveled and retraced and traveled agaln. It is #o hard a task to do even the day's work bravely and honestly; how had this been possible I asked. “It's not thinking of the road you come by, but always of the end, that makes & thing possible, Otherwise—" 2nd he shook his head Such is the power of an idea. The professor perched upon one un- dling chair and I upon a Clara arlor of Sant bare, another in the the unfailingly chill, e parlor the exclusively tation ntle in- of shy little man tic aspect that instinc- Father Montgorm d, mod: und, g stly, ave an upw of the c abitually curve like u zht- nsitive, of pur- cent moon to his I ascetic, lling a story ywavering r; I'm not gh p strang- Father and many let- dressed that way— here, I supposi t the background of ge, nor yet the clean- makes “Father” the tongue. es a benignity, an astness and re- ceptivity limpidity of gaze that never lie in the restiefs eyes that seek the fleeting dollar, and above all there is the round, full, bald head, the splen- daid, dom: ke head with its height chiefly above the ears. It is the Jesuit- ical head—the distinguishing mark of the big-brained men who have made their order powerful. Should I meet him on Market street, instead of in the cloistered quiet of Santa Clara College, and he take off his hat to me, my impulse still would be to greet him with “Father.” The world has a right to expect something of & man with a head like that. “T'm not & flying machine crank,” he disclaims at once. “T've mot devoted my whole life to the development of Qw MONG the numerous problems which concern the parents and the educators of America there is one of peculiar interest to the authorities of the secondary or high schools and the parents whose children attend or expect to attend such schools. In fact, it is held by some careful ob- servers of conditions prevailing in sec- ondary schoo! life that the most vital problem of high school life of the pres- ent time is that of high school frater- nities, their effect and consequence upon the public school system of the United States. It is of such importance that investigation of their influence is being made by asuthorities in different ons of America, and agitation in press for their abolition is not in- quent In order to understand the problem of high school fraternities saright, a short description of the system is nec- school fraternity is a volun- 4 association or society composed for the most part of pupils attending high school at the present time or who have attended in the past, secret charac . selecting its membership standards arbitrarily its members, closely 1 its larger features the es which exist in colleges and universities, and also the frater- nal organizations of adult society, such gs the Masons, the Elks, the Odd Fellows, ete. Most fratern cated ir academ s have branches lo- ent high schools and s. These branches are called chapter: hd usually contain some- where between five and thirty mem- bers or even more. Some fraternities are merely local, having no connegtion with other chapters, but existing in- dependently. Most local fraternities, however, aim at ceventually becoming this one idea, to the exclusion of every- thing else. It is true that all my life the thought of flying has held a fas- tion for me, the problem of aerial has interested me beyond everything else, and I have worked at it unremittingly—but not at that alone. I have been interested in mechanics, in electricity, in astronomy—"" And in astronomy alone Professor Montgomery’s researches and discover- fes and deductions, us contribution to the sum of knowledge would make of him a noted man in the sclentific world if he had not the other day turned loose a flylng machine that really fiies and thus overshadowed all other interests in him. “I have always been Interested in all the phenomena of nature. I think that is my natural bent of mind. My earli- est recollection—and it is such an early recollection that I'm half afraid to tell Yyou it is of the time when I was only three and a half years old—is of the curiosity excited by this in- terest. The circumstance Is as clear in my mind as though It were an occurrencé of yesterday. My father had taken me with him on a drive and left me sitting in the rig while he attended to the Dusiness that had occasionsd the drive. While I was I observed for the first ng shadows on the sur- rth. When he came back I asked what made them. Very kindly and simply he tried to make clear to my mind (he rotation of the earth and his explanation suggested a regularity of mcvement that must, of course, produce 2 reguiarity of effect. I observed variation, irregularity, and for years this phenomenon troubled my mind. I was ashamed to tell that I did not unders and ask again for the fuller cxplanation he would so gladly have So the little put the question straight And as th to 1 =u has the man d and nature has taken him into her « imparted to him her sec overtly, indirectly and a n with free and open hand. When Telegraph 1 and Forti- eth street in Oaklund was: still part of a ranch this flying machin: that really files was born in the mind of a boy playing in the ranch barnyard: not fuil-winged, of cou but in the tor- menting form of a question. “When I was a boy of sixteen and we were living on our ranch at what is now Telegraph avenue and Fortieth street in Oakland, 1 was playing in the barnyard, as boys will, shying a piece of tin in the Something in the way it came down, curving and apparently resting at different points in the air, arrested my attention. It stracx me as weird. Why didn't it come straight down? Why did it curve and turn and settle—seemingly suspended in midair for an instant? It struck me as weird—that is the only word that conveys the impres- sion it made on my mind, and the im- pression remained because it puzzied me. “It is with this incident that I con- nect my first ideas of aerial naviga- tion that were more than merely vis- jonary and esthetic, more than mere~ ly the vague desire to fly.” The same boy on the same Oakland ranch chasing his grandmother’'s geese into flying from one end of the ranch to the other, much to the amazement of the geese and the mys- tification of the good grandmother, is another picture in the evolution of the flying machine that really flies. “It always seemed to me that the secret of aerial navigation lay in the discovery of the principle of a bird's flight—that the successful airship would not be modeled on the balloon nor dependent on its buoyancy. The fiying of wild geese interested me in consequence and as I couldn’t get near allied with some larger organization. The chapters correspond to the sub- ordinate lodges in the fraternal so- cieties of aduits. The fraternities have chapters lo- cated in the high schools of different cities of California, of the Pacific Coast and of the United States. In fact, the high schools of the whole country are permeated with a net- work of these student organizations, which find their most fertile fleld in the schools of the larger cities, al- though they are being gradually ex- tended to smaller localities. The exact number of fraternities would be hard to ascertain. Each fraternity is organized under a constitution and set of by-laws, and posesesses a ritual of initiation cere- monies. which are the same for all chapters of the same fraternity wher- ever they may be located. ach fra- ternity has a name. consisting of some combination of Greek letters, such as Theta Chi, Gamma Eta Kap- pa, Alpha Sigma, etc., and the mem- bers wear a pin, which is a monogram or other device serving to indicate to which fraternity the wearer belongs. They have grips and means of recog- nizing fellow members. Qualifications for membership vary. In general it may be said that a boy or girl must be agreeable, of .compan- lonable qualities, of attractive person- ality and of sociable nature and dis- position. Boys' fraternities, as a rule, select their members from the class of boys who might be called “good fel- Jows"—that is, one prominent in ath- letics or soclally attractive is likely to be invited to join. Girls of similar tastes and #habits and ways of life usually group together. Children of families which move in the same social sphere usually are picked for member- ship, although it does not necessarily ;olllew that all such will be invited to join. enough to them for close and careful observation, I taught my grandmoth- er's flock of geese to fly. I used to drive them down to the extreme end of the ‘ranch and then by cracking a whip behind them compel them to rise and fly to the other end of the ranch. I had them trained so that they knew just what I wanted when I would crack the whip, and I think it was always a matter of wonderment to my grandmother why her geese could fly so much farther and batter than her felghbors.” A chuckle at the recéllection of the boyish prank that-was sofar from mis- chief showed how much a §han ascien- tist can be. “For years T made models of alrshxps of all sizes, always using the plane sur- face as other experimenters were doing, and always failing to solVe the problem of aerial navigation. ““We moved to San Diego to a ranch there, and 1 worked at ranching and. in all my leisure hours, in.all the hours I could spare from other labors. I tried to get at the secret of aerial naviga- tion. I made model after model and N NN N S NN N N NN N NN DD R R R e NG SO SRR NG P00 00050 launched it, only to meet disabpoint- ment, and then—" “You gave up—you coucluded it eouldn’'t be done?” 5 “Why, no,”in mild surprise that such a thoughit might have entered his mind. “I have always believed it could be done. I concluded that I didn’t know how, that my experiments had been at fault, that they had not been along the right line. So I went back—" “To the beginning?” “Yes—to the beginning, to see where the mistake lay. I quit making models Professor J. J. Montgomery. of airships. I investigated the relation of surfaces to the wind and the effect of wind on surfaces. I found that wind has form that is affected and changed by the contact with or approach to a concrete body. I fouid that the wines of birds are of wonderful mechanism perfectly adapted to the utilizatjon of the forms of the wind, and sc, throwing aside all the theories that involved the plane surface, I have tried to follow the construction of the bird’s wing in the makjng of my airship. ’ “I went to the Aeronautical Congress that was held in Chicago during the World's Fair in 1893 and got there just in time to hear Professor Langley’'s papeg on the ‘Thezmernal Work of the Wind.” His observations agreed with mine, and that gave me a feeling of greater assurance, a sory of moral sup- port, for there is a certain degree of comfort to be got out of having some one else see things as you do. He had observed certain facts in relation to the wind, and I had found out the rea- son for them, and so the paper was brought up again for discussion.” And as a result the quiet, unassum- ing little man cf priestly cast, who had come out of California unknown and unheralded, was regarded with interest and respect and attention by that gath- ering of scientists of world-wide fame. Then he came back to California, buoyed with the conviction that he was on the right track at last. “I felt that my theory was the key to the problem of aerial navigatios, and I worked it out in the following two years. It required the nicest precision 4n mathematical calculation, of course— in conic sections chiefly.” There were reams and reams of fig- RGN N0 E00000e WWW 2 THE PROBLEM OF HIGH SCHO By Frank Tade, Principal Sncramento High School Some think that only the. children of the well-to-do or of those prominent in the soclal life of a community are ex- clusively members of fraternities, but suth is not the case, for, on the one hand, some frafernity members are self-supporting, and, on the other hand, some boys and girls, though coming from the famlies of the rich or well-to- do or socially prominent classes, are refused membership. Again, all those who measure up to the standards usu- ally applied by members of fraterni- ties are not necessarily invited to join, as personal spites and jealousies fre- quently operate to keep out individu- als otherwise qualified, Some fraterni- ties do not restrict membership exclu- sively to those who attend high school. It would be considered extremely bad form for a boy or girl to ask a frater- nity to be admitted to membership. It must be gained through Invitation ex- tended by the fraternity to the indi- vidual. Before joining a fraternity an in- dividual deemed a desirable acauisition by a fraternity is “rushed.” That is. he is subjected to a process calculated to impress him with the idea that it will be to his advantage to join this or that particular fraternity. He is shown some unusual attention and considera- tion and courtesies by the members of the fraternity who are rushing him. all intended to win him to membership. One may be rushed at the same time by several fraternities, which often compete keenly wl}h each otgler to :fi- ciire -a Wll" desirable candi- date. "Apparcntly the fraternities lre or- ganized for the: purpose (1) of culti- vating intimate friendships among their members both during attendance at school and in after life. (2) of mu- tually assisting other in the varjous details of the life in which the youth of modern times moves. and (3) ‘of providing through joint effort op- portunilies for the enjoyment of so-, cial pleasures by themselves and their” Zuests. The most prominent purpose, as seen by the general observer, is to provide ways and means and opportunities for having a “good time" sociallv while attending school, in the forms of dances, parties, picnics and entertain- ments at the homes of members. in the accomplishment of which purpose the fraternities are & pronounced success. It is claimed that participation in the proceedings of the meetings of the fraternities offers some opportunities for self-improvement of their mem- bers, in the knowledge gained of/par- liamentary procedure and train! in expression of one's ideas. The fraternities hold meetings" at which they transact their Dbusiness. consisting of election of new members. initiations, discussion of matters of- common interest, such ag plans for some joint enterprise and enjovment of some light form of repast. Some fraternities endeavor to include some- thing in the nature of literary exer- cises. These meetings are uvsu " held at regularhi‘ ntervals at the homes of members. although in some cities a gart of club-room is rentef for head- quarters. Some fraternities have dis- trict or State conventions. Some have national eonventions. Inyestigation of desirable eandidates for rilembership is directed to the gram- mar gchools, and when a desirable pu- pil enters high school he is “rushed,” and if he cares to join and has permis- sion of his parents; he Is initiated, Some of the fraternities initiate their candidates into through two ceremonies. These are (1) ‘hich the public, ‘“outsile’” work, W usually ¢ e harmless - sense, putting the various eulous the pupti ia 4 fon-fedgea s uj % member the frate ty, mflm Qo l“ th: rlslltl embership usually N RO (BN SN BN RO ORI and privileges of a “frat.” Only mem- bers of a fraternity are present at its meetings, 'and its transactions are se- cretly and jealousiy gfarded. Bésides their business meetings, the fraternities usually give parties and picnics, which are the most elaborate social events among the high school pupils. Invitations to these affairs are saught after eagerly, as the partles are usually excellently managed and afford much pleasure to the participants. In the life of the student body at school the fraternities - are active in several ways. Their members act Jjointly and in apmparent concert in ac- complishing their ends. For instance, definite policies in school politics are decided upon. The frats unite their forces and vote in oppesition to the non-frats to secure the election of a frat to a position, such as president of the student body, or editor of the school paper, or captain of the football team. Fraternities consider it a matter of pride and satisfaction to have among their numbers the leaders in students’ affairs. It is regarded as an honor for a fraternity to have its members direct activities in student life. They “point with pride” to this or that boy as cap- tain of the baseball team or president of his class,"and incidentally as a mem- ber of their own fraternity. This ambi- ‘tion leads to rivalry and competition among the fraternitles, as well as struggles with the non-frats. Inter- trat rivalrv sometimes leads to their undoing as against their common en- emy, the mon-frats, but usually the frats come to an agreement as to what line of action is necessary for their common success. .~ Frats tend to group together in the - schools, ference, as a. .:neul rule, for asso- ates who Hoag toltraurnitl-. This. nevitably leads to a separation ng . quite a mar] ured pages, endless problems to be worked out to the feather-edge of an infinitesimal fraction, the air pressure and the resistant surfaces to be fitted to each other to the last hair’s breadth, weary days and long. still nights of patient labor to be done—the long, dry, dreary road of detail to be traveled. “I worked it all out ten years ago, and laid it aside.” | Ten years ago! “The principle upon which the Santa Clara—the machine we have tested— was constructed was formulated ten years ago. I couldn't go on with it then, so I had to put it aside until the opportunity for building and testing it should come.” So after a lifetime’s dreaming and experimenting and Investigating this quiet, patient, persistent man went on with the urgent, immediate affairs of life with his triumph in his pocket, as it were. “How could you wait?” I asked him. “Why, I knew it could be done when the time came. I had experimentpd enough to know the principle was the right one—that it solved the problem of controlling an airship in the air.” Sclentists are a strange folk, aren’t they? The time did come—at last. Two years ago Professor Montgomery began again the making of models of airships, according to the new plans, and this time they worked. “f went out to Leonard’s—my friend Mr. Leonard's place. We stretched a cable between two hilltops about a hun- dred feet high, and from this cable we liberated models of my machine in every conceivable way—large models and small, with weights in proportion. They were liberated right side up and wrong, dropped head first and tail first, and in every instance they righted themselves in a very short distance and sailed to the earth right side up. alighting as safely as a bird. The tests were all encouraging—satisfactory. “Then came the test of the large machine, adapted to a man’s weight. This was the supreme test—for it in- volved the jeopardizing of a human life.” Perhaps to the mind this would have been a small matter—but the willingness of Pro- fessor Montgomery to send up a man in his flying machine is the measure of his faith in it. The world knows now how well found=d his faith was for the demon- stration of its powers has been made, and all the world knows now that it is a flying machine that flies—yet there was a moment when that faith was se- verely strained. “It was,” says Father Bell, “the first time a man went up in it. The ma- chine was attached to the balloon by ropes, as the basket would be, and Maloney, the man who went up in it, was sitting in it, of course. The bal- loon, big and powerful, gave a jerk as it went up that snapbed off the wings of the flying machine. There was nothing to be done, for the thing was on its way up, and then to hadd peril to the situction the balloon struck a current that turned it over, and if Maloney had tried to cut loose he would have fallen into the balloon to certain death. He kept his head, the balloon partly righted itself and Ma- loney found to his surprise that the machine was supporting him even without its wings and that he was com- ing down more slowly.than the balloon. That-gave him more confidence in it than he would Have had without the accident, he says—but you can imagine how Professor Montgomery felt! With what thankfulness he saw him alight.” ‘While all the world is watching for the man who will solve the problem of aerial navigation California produces him.. Professor Montgomery is a Califor- purely sclentific OL FRATERNITIES = ive offices, and thereby secure direction of student affairs. Discipline and scholarship are found to be affected detrimentally by the existence‘of the frats in schools, according to the results of investiga- tions in different Schools of the coun- try. It is undoubtedly true that some of the best scholars are members of the fraternities. It is equally true that the minds and thoughts of some members are so absorbed by frater- nity affairs that neglect of studies fol- lows, and scholarship is impaired. Fraternities tend to affect the esprit de corps of a school and destroy uni- ted school spirit. They tend to pro- voke jealousy among some of the pupils in the schools. They create hard feelings. They originate feelings of envy and wounded pride among some of the pupils. They provide oc- casions for dissensions among pupils in matters of common student activity. Keen disappointment and a contipu- ous state of dissatisfaction affect some non-frats who are not invited to join. Fraternities cause disappoirtment to some and inspire others with a false sense of their own importance and su- periority to others not glected to mem- bership. They encou clannishness. They ilitate against solidarity in the communal life of a school. They sub- Stitute a distracting element in the lives of pupils who might otherwise concentrate thought and attention on the immediate purpose of their school lives. The cultivation of social forms, manners and pleasures has become a very substantial part of the life of some pupils, as a direct result of the exl:;‘tneo “the tratcrnudi:;‘ in tb; public ools. Friendships an natural I:.}lrelu ‘:!‘xm be;n' ml'nker- rupted a gl fra- ternity -m:"v‘ The “ difficulties of these which accompany the fraternity 'n- tem as conducted at r-ont hm his father, Zachariah Mon:zomery. came across the plains from Kentucky: so did his mother. All his life has been spent here; he was educated at St. Ignatius College, and while he has been working out the problem that concerns all the world he has beeq teaching hers in California, up in Humboldt and at Santa Clara College. With scientific precision and the cau- o tion of an hcnesty that will not be ap- plauded more than its due, he says about his flying machi “You must not think that the success of these experiments of mine means that in a few weeks or a few months, or a year, flying g@achines wiil be car- rying passengers and plying between San Francisco and New York and Paris. It means that the prablem of aerial navigation js selved—that the ~ question of controlling a flylng ma- chine, of flying in the teeth of the wind, with the wind or across the wind, ip an- swered, that it is no longer a thing at the mercy of the air currents. Remem-~ ber, this machine has to be takem up from the earth, that it cannot rise of itself. The problem of lifting it has yet to be solved, of carrying passen- gers, of making it a utility. All these things cannotibe accomplished at once nor, perhaps, by one man. It must be remembered that the ocean carrier, the steamship as we know It to-day, Is the result of centuries of evolution and im- provement tror;l the first frail, uncer- tain bark man launched upon the waters—when that bark was controlled that was the first step in navigating the waters; this is the first in navigat ing the air.” . Professor Montgomery's ®evotion to an idea—from that day forty years ago, when his childish hands longed > grasp the trailing skirts of the clouds— has been constant and self-sacrificing, but not entirely Quixotic, His suits for damages against Cap- tain Baldwin, who he says appropriated some of his ideas for the California Ar- row, a balloon with a propeller, show that. He will punish treachery and hold his own. g He recognizes the commercial as well as the scientific value of his discovery and invention. “A man would be a fool,” he says, “who would not seek to benefit by his years of labor such as mine has been.” But the real triumph for him is not after all in the world's acclaim and the money returr. There are the friends of his heart whose belief in him will be justified, to whom he will justify him- self. And there are gentle regrets that some who believed are not here to share his triumph. Father Neri, who was the head of St. Ignatius College when he was a boy there. who in his time was a sclentist, and who turned the first electric light on California. was one of those. “Father Neri,” says Father Bell, who was also a boy at St. Ignatius them, “used to Bay again and again to the rest of us, ‘You'll hear of Montgomery some day.’ He'd have been happy to have seen his words come true.” Ard there was one nearer and dear- er—the father whose sympathy and undarstanding are a cherished memory. There surely is a great joy Im an achievement as Professor. ery’s—to see at last the work of brain and hands, the incarnation of life-dream scaring In heaven’s biue; . it would be but a poor, cheap . creature, dry as husks, unworthy sad incapable of such achievement, who could rot feel such jow. i Joy he feels—and the only cloud upos it is that the dear father could not share it. Our common notion is that selence is dry as dust, yet inventing a flying ma- \ chine is not after all a mere matter of conic sections, you see. could probably be eliminated by proper sSupervision on the part of the parents. Fraternities are a natural growth, orig- inating in a desire to ape college fra- ternities and also out of the club fever or society fever that has become wide- spread throughout America of late years. It is the natural thing to ex- pect that the youth of America, ob- servant and imitative, would be infect- ed with the spirit that animates their elders and parents. The atmosphere in which our modern life moves makes this very thing possible and natural | among the children. It is a reflection of the prevalent conditions in adult so- . cial life and to that extent its evils must be charged up to the systemy which is approved by adults and pa= tronized by them. ‘The chief source of detriment arising from high school- fraternities lles in the immaturity of the members. They do not see the vital and Important things of life in their right : Their perspective is faulty. ally a fraternity is a harmiess As it operates in actual practice are many objectionable ing from the immaturity of affected, the deterioration of selection of members, and heartburnings and disaj experienced by the favored few side and the many outside, and substitution of the unessential for essential pursuits of youthful ard the genmeral inversion of the poses of that important period of High school fraternities are, in the timation of many careful thin! ififififi !gm §F f