The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, August 23, 1903, Page 2

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

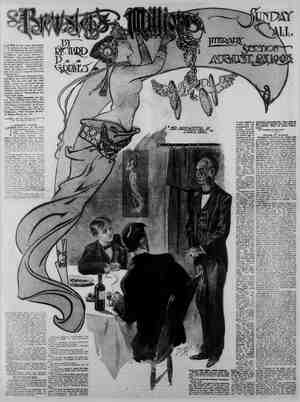

2 THE SUNDAY CALL. hough not in his presence. But the ex- istence of miss Barbara Drew may have had something to do with the feeling be- tween the two men. As he left the directors’ room, on the afternoon of the meeting, Colonel Drew e up to Monty, who had notified the cers of the bank that he was leaving. ‘Ah, my dear boy,” said the colonel, king the young man’s hand warmly, you have a chance to show what vou can do. You have & fortune, and with judgment you ought to be able to it. If T can help you in any way e and see me.” Monty thanked him. “You'll be bored to death by the raft of people who have ways to spend your money,” continued the colonel. *“Don't n to any of them. Take your time. You'll have a new chance to make money day of your life, so go slowly. I'd been rich years and years ago If I'd had sense enough to run away from promoters. They’ll all try to get a whack Keep. your eyve open, e rich young man is always ng morsel.” And after @ moment's n he added, “Won't you come out ine with us to-morrow night?” at your money. ty 11 MRS. AND MISS GRAY n Fortieth street. For Brewster had regarded foned me as his own. o been her grand- was one of ploneers in that part of the town. It was there she was born; Ir nt old parior she er girlhood, her widowhood were d Mont- her ima hip Peter Brewster h and as brother sister. Mr. Brewster was generous in pro- Edwin Peter Brewster. he was not niggardly ng of a struggle for 1 swept away her from her father, me into his ncelve no i Brewster tried ch he comld t giving deep aj ired wild desig) were quickly astened. by elec- r d Broadway walked eagerly off into the f the numeral. He had not yet the point where he felt like scorn- ough a roll of bank: 1gly away in a pock to swell with sndden faithful generations, was sweeping ! s from the sidewalk to the house ng. “Nice of S ebbed from Hendrick, who did not « ch as look up from his work human clam nified yes ever, Hend- let himself in with his own threw his hat on asly balted seated n of the fatted ght of that ss had gone. I didn’t dare e must be re- rich relatives, Peggy; if T this money would make any would give it this minute.” nse, Monty said. “How ake a difference? But you must t 3t is rather startling. The friend r youth leaves his humble dwelling ) night with his salary drawn for weeks ahead. He returns the fol- a dazzling millionaire.” ad I've begun to dazzle, any hought it might be hard to look o = the part Well, T can't see that you are much hanged.” There was a suggestion of a 1aver in her voice, and the shadows dfa prevent him from seeing the quick itted across her deep eyes. it's easy work being a mil- explained, “when you've lar inclinations.” ibilities she added. I'll never get as much ut of my abundant riches as I did f financial embarrassments.” But think how fine it is, Monty, not ver to wonder where your winter's over- at is to come from and how long the will last, and all that.” h, T never wondered about my over- =: the tailor did the wondering. But I wish 1 could go on iving here just as before. I'd a heap rather live here than at that gloomy place on the avenue.” “That sounded like the things you used to say when we played in the garret. You'd a heap sooner do this than that— n't you remember?” “That's just why I'd rather live here, Peggy. Last night 1 fell to thinking of that old garret, and hanged if something n’t come vp and stick in my throat so tight that I wanted to cry. How long has it been since we played up there? Yes, and how long has it been since I read ‘Oliver Optic’ to you, lying there in the garret window while you sat with your back against the wall, your blue eyes as big as dollars?" “Oh, dear me, Monty, it was ages ago— twelye or thirteen years, at least,” she cried, a soft light in her eyes. “I'm going up there this afternoon to see what the place is like, ' he sald eager- ly. “And, Peggy. you must come, too. Maybe I can find one of those Optic books, and we'll be young again.” “Just for old time's sake,” she said im- pulsively. “You'll stay for luncheon, too. “I'll bave to be at the—mo, I wop't, either. Do you know, I was thinking I had to be at the bank at 12:30 to let Mr. Perkins go out for something to eat? The millionaire habit isn't so firmly fixed as I After & moment's pause, in growing seriousness changed the atmosphere, he went on. haltingly, uncertain of his position: T nicest thing about having all this money is that —that—we won't have to deny ourselves anything after this.” It did not sound very tactful, now that it was out, and he was compelled to scrutinize rather intent- ly a familiar portrait in order to maintain an air of careless assurance. She did not respond to this venture but he felt that she was looking directly into his sorely- tried brain. “We'll do any amount of dec- orating about the house and—and you know that furnace has been giving us a lot of trouble for two or three years— he was pouring out ruthlessly, when her hand fell gently on his.own and she stood straight and tall before him, an odd look in her eves. “Don’t—please don't go on, Monty,” she said very gently but without wavering. “I know what you mean. You are good and very thoughtful, Monty, but you really must not.” “Why, what's mine is yours—" he be- gan. “I know you are generous, Monty, and I know vou have a heart. You want us to—to take some of your money’— it was not easy to say it, and as for Monty, he could only look at the floor. “We cannot, Monty, dear—you must never speak of it again. Mamma and I had a feeling that you would do it. But don’t you see—even from you it Is an offer of help, and it hurts.” “Don’t talk like that, Peggy,” he im- plored. & s “It would break her heart if you offered to give her money in that way, She'd hate it, Monty. It is foolish perhaps, but you know we can’t take your money.” “I thought you—that you—oh, this knocks all the joy out of it,” he burst out desperately. “Dear Monty!" ,“Let's talk It over, Peggy: you don't understand—" he began, dashing at what he thought would be a break in her re- solve. ¥ “Don’t!” she commanded, and in her blue eyes was the hot flash he had felt once or twice before. He rose and walked across the floor, back and forth again, and then stood be- fore her, a smile on his lips—a rather pitiful smile, but still a smile. There were tears in her eyes as she looked at him. “It's a confounded puritanical preju- dice, Peggy,” he said in futile protest, “and you Know it.” “You have not seen the letters that came for you this morning. They're on the table over there,” she replied, ignor- ing him- He found the letters and resumed his seat in the window, glancing half-heart- edly over the contents of the envelopes. The last was from Grant & Ripley, at- torneys, and even from his abstraction it brought a surprised “By Jove!" He read it aloud to Margaret. September 0. Montgomery Brewster Esq., New York. Dear Sir: We are in receipt of a com- munication from Mr. Swearingen Jones of Montana, conveying the sad intelli- gence that your uncle, James T, Sedg- wick, died on the 24th inst. at M— Hos- pital in Portland,: after a brief illness. Mr. Jones by this time has qualified in Montana as the executor of your uncle's will and has retained us as his Eastern representat!’ He Incloses a copy of the will, in which you are named as sole heir, with conditions attending. Will you call at our office this afternoon if it is convenlent? 1It,Is important that you know the contents of the instrument at once. Respectfully yours, GRANT & RIPLEY. For a moment there was only amaze- ment in the air. Then a faint bewildered smilé appeared in Monty’s face, and re- flected itself in the girl’s. “Who is your Uncle James?" she asked. I've never heard of him.” “You must go to Grant & Ripley at once, of course,” “Have you forgotten, Peggy.” he re- plied, with a hint of vexation in his voice, “that we are to read ‘Oliver Optic’ this afternoon?" 5 1v. *1¢ A SECOND WILL. “You are both fortunate and unfor- tunate, Mr. Brewster,” said Mr. Grant, after the young man had dropped into a chair In, the ouice of Grant & Ripley the next day. Montgoméry wore a slightly bored expression, and it was evident that he took little interest in the will of James T. Sedgwick. From far back in the re- cesses of memory he now recalled this long lost brother of his mother. As a very small child he had seen his Uncle James upon the few occasions which breught him to the heme of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Brewster. But the young man had dined at Drew’s the night before and Parbara had had more charm for him than usual. It was of her that be was W-157/4 thinking when he walked into the ofce of Swearingen Jones' lawyers. “The truth is, Mr. Grant, I'd completely forgotten the existence of an uncle,” he responded. “It is not surprising,” said Mr. Grant, genfally. “Every one who knew him in New York mineteen or twenty years ago believed him to be dead. He lcft the city when you were a very small lad, going to Australia, I think. He was off to seek his fortune, and he needed it pretty bad- ly when he started out. This letter from Mr. Jones comes like a message from the dead. Were It not that we have known Mr. Jones for a long time, handling affairs of considerable importance for him, I should feel inclined to doubt the whole story. It seems that your uncle turned up in Montana about fifteen years ago and there formed a stanch friend- ship with old Swearengen Jones, one of the richest men In the Far West. Sedg- wick's will was signed on the day of his death, September 24, and it was quite natural that Mr. Jones should be named as his executor. That is how we became interested in the matter, Mr. Brewster. “I see,” sald Montgomery, somewhat SRR Sl R S S R S e 2 0 e 9 & AT puzzled. “But why do you say that I am both fortunate and unfortunate?” “The situation is so remarkable that you'll consider that a mild way of ng it when you’ve heard everything. think you were told, in our note of yesterday, that you are the sole helr. Woell, it may surprise you to learn that James Sedg- wick died possessed of an estate valued at almost seven million dollars.” Montgomery Brewster sat like one pet- rified, staring blankly at the old lawyer, who could say startling things in a level voice. “He owned gold mines and ranches in the Northwest and there is no question as to their value. Mr. Jones, in his let- ter to us, briefly outlines the history of James Sedgwick from the time he landed in Montana. He reached. there in 1838 from Australia, and he was worth thirty or forty thousand dollars at the time. Within five vears he wag'the owner of e huge ranch, and scarcely had another five years passed before he was part owner of three rich gold mines. Posses- sions accumulated rapidly; everything he touched turned to gold. He was shrewd, careful and thrifty, and his money was B (/7 =g o WERE CUSOED 1) 3 WV ol handled with all the skill of a Wall-street financier. At the time of his. death, in Portland, he did not owe a dollar in the world. His property i{s absolutely unin- cumbered—safe and sound as a Govern- ment bond. It's rather overwhelming, isn't {1?” the lawyer concluded, taking note of Brewster's expression. “And he—he left everything to me?” “With a proviso.” “AR!" “I have a copy of the will. Mr. Ripley and I are the only persons in New York who at present know its contents. You, I am sure, after hearing it, will not di- vulge them without the most careful de- liberation.” . Mr. Grant drew the document from a pigeonhole in his desk, adjusted his glasses and prepared to read. Then, as though struck by a sudden thought, he laid the paper down and turned once more to Brewster. “It seems that Sedgwick never married. ‘Your mother was his sistér and his only known relative of close connection. He was a man of most pecullar tempera- ments, but in full possession of all men- tal faculties. You may find this will to be a strange document, but I think Mr, \\‘\\ Jony the executor, explains any mys- tery”t‘hn may be suggested by its terms. While Sedgwick’'s whereabouts was un- known to his ald 'friends in New York. it seems that he was:fully posted on all that was going on here. He knew that you were the only child of your mother and therefore his only nephew. He sets forth the dates of your mother's mar- riage, of your birth, of the death of Rob- ert Brewster and of Mrs. Brewster. He also was aware of the faet that old Ed- win Peter Brewster intended to bequeath a large fortune to you—and thereby hangs & tale. Sedgwick was proud. When he lived in New York he was re- garded as the kind of man who never for- gave the person who touched roughly upon his pride. You know, of course, that your father married Miss Sedgwick In the face of the most bitter opposition on the part of Edwin Brewster. The latter refused to recognize her as his daugh- ter, practically disowned his son, and heaped the harshest kind of calumny upon the Sedgwicks. It was commonly believed about town that Jim Sedgwick left the country three or four years after his marriage for the sole reason that he and Edwin Brewster could pot live the same place. So deep was his hatred of the old man that he fled to escape killing him. It was known that upon one occasion he visited the ofice of his sister’s enemy for the purpose of slaying him, but sométhing prevented. He car- ried that hatred to the grave, as you will see.” Montgomery Brewster was trying to gather himself together from within the fog which made bimself and the world unreal. “T believe I'd like to have you read this extraor—the will, Mr. Grant,” he said, with an effort to hold his nerves in leash. Mr. Grant cleared his throat and began in his still volce. Once he looked up to find his listener eager, and again to find him grown indifferent. He wondered dimly if this were a pose. In brief. the last will of James T. Sedg- wick bequeathed ‘everything, real and personal, of which he died possessed, to his or ephew, Montgomery Brewster of New York, son of Robert and Louise Sedgwick Brewster. Supplementing this all-important clause there was a set of conditions governing the final disposition of the estate. The most extraordinary of these conditions was the one which re- quired the heir to be absolutely penniless upon the twenty-sixth anniversary of his birth, September 23. The instrument went into detail in re- spect to this supreme condition. It set forth that Montgomery Brewster was to have no other w y possession the clothes which covered him on the September day named. He was to begin that day- with a penny to without a single article of jew niture or finance t he could call own or could thereafter reclaim. At nine o'clock, New York time, on the morning of September 23, the executor, under the provisions of the will, was to make over and transfer to Montgomery Brewster all of the moneys, lands, bonds, and Inter- sts mentioned in inventory which ac- companied the ‘will. In the event that Montgomery Brewster had not, in every particular, nplied with the . to the full satisfaction cutor, Swearengen Jones, the estate was to be distributed among certain institutions of charity designated in the instrumen Underlying this im- require- perative injunction of James Sedgwick was plainly discernible the motive that prompted it. In almost so many words he declared that his heir should not re- ceive the fortune if he possessed a sing! penny that had come to him, shape or form, from the man he hated, Edwin Peter Brewster. While Sedgwick could not have known at the time of his death that the banker had beg one million doll to his grandsom, it was more than apparent that he expected the young man to be enriched liberally by his enemy. It was to preclude any possible chance of the mingling of his fortune with the smallest portion of Edwin P. Brewster's that James Sedgwick, on his deathbed, put his hand to this asto ing instrument. There was also a clause in which he undertook to dictate the conduct of Montgomery Brewster during the year leading up to his twenty-sixth anniv sary. He required that the young man should give satisfactory evidence to tTe executor that he was capable of manag- ing his’'affairs shrewdly and wisely—that ke possessed the ability fo add to the for- tune through his own enterprise; that he should come to this twenty-sixth anniver- sary with a fair name and a record free from anything worse than mild forms of dissipation; that his habits be temperate; that he possess nothing at the end of the year which might be regarded as a “vis- ible or invisible asset”; that he maké no endowments; that he give sparingly to charity; that he neither loan nor give away money, for fear that it might be re- stored to him later; that he live on the principle which inspires a man to “get Hls money’s worth,” be the expenditure great or small. As these conditions were pre- « ribed for but a single year in the Nfe of the heir, it was evident that Mr. Sedg- wick did not intend to impose any restric- nurj after the property had gone into his s ‘How do you like it?" asked Mr. Grant, as he passed the will to Brewster. The latter took the paper and glanced over it with the air of one who had heard but had not fuily grasped its meaning. “It must be a joke, Mr. Grant,” he £ald, still groping with difficulty through the fog. “No, Mr. Brewster; it is avsolutel; - uine. Here is a telegram from me’ g—:- bate Court in Sedgwick's home county, received In response to a query from us. It says that the will is to be filed for pro- bate and that Mr. Sedgwick was many times a millionaire. This statement, which he calls an Inventory. enumerates his holdings and . their value, and the footing shows $6,345,000 In round numbers. The investments, you see, are glit-edged. There is not a bad penny in all those millions.”" ““Well, it is rather staggering, isn't 1t7 =ald Montgomery, passing ..is hamd over his forehead. He was beginning to com- prehend. “In more ways than one. Y hat are you going to do about 1t?* “Do about it?" in surprive. mine, isn't 1t?” “It is not yours until next September,” the lawyer quletly said. “Well, I fancy I can wait,” sald Brew- ster with a smile that cleared the air “But, my dear fellow, you are already the possessor of & millichr~ Do you forget that you are expected to be penniless a year from now?” “Wouldn't you exthange a million for seven millions. Mr. Grant?” “But let me inquire how you propose do- ing it?" asked Mr. Grant, mildly. “Why, by the simple proeess of destruc- tion. Don't you suppose I can get rid of a million In a year? Great Scott, who wouldn’t do it! All I have to do is to cut a few purse strings and there is but one natural conclusion. I don’t mind be- “Why, it's