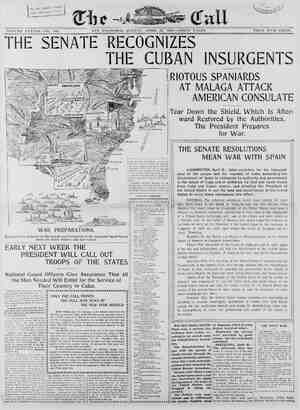

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, April 17, 1898, Page 23

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

NCISCO CALL, SUND AY, APRIL 17, 189S. 23 A\ HAVE been talking to the motor- man. ot on his car; dear me, no. I wouldn’t have the heart to do that in the face of the company's gentle plea to the contrary, which is displayed above his+head, but I tracked him to his lair, as it were, and finding him in his variety by no means the fierce and murderously inclined monster that he is frequently represented to be I con- rsed with him without fear. I talked with him concerning his avo- cation, its duties and its dange and knowing well what a large proportion the gene public thinks of him I essayed to find cut what he thinks of the human tide through which hesteers his unwieldy craft, what causes he as- signs for the accidents which occur and which just miss occurring, and how life seems from his standpoint. 1 discovered t he has his griev- ances; that he considers himself often x tres nd that he does not maiming and Kkilling human running over dogs and into fairly about be herses and smashing vehicles just for ngs the fun of the thing. Here is what he, in his various indi- vidualities, said to me: F. 8. GOGGIN—Whenever t on le about it, that there are the time ins they do. people that they haven't any call to look out for them- , but wander off and on car as they please, without pay- attention to motormen n to the cars unle: N to hit them. Ne v @ nt that happens to grown people is 1 by their own criminal care- and men and women are ke in this respect. If those are the quickest to blame ¢ accident would just day rid on the front seat straight down the track I v would view the matter 1tly erward. ot a day that some narrow escape does ur, but when no one is hurt the that the motorman’s coolness and ss saved a life that its owner's € nea acrificed generally passes unnoticed worst shake-up that I have had down on Mission street. I following behind a heavy truck a boy ran out from behind another team coming toward me, right across my track, within two feet of me. If I had hurt that boy that I never saw until he was almost under the car I should have been blamed, of course, but it was almost r acle that 1 didn't. Such things constantly happening and will until children are taught not in ther f the streets, 4 any one car line there is a great but the wonder to oc- in- lately had be aduits learn to nd off cars pre erly, look out fc cars on both trac and pay attention when the gong rings. M. SCHUMACHER—I have been a car an for twenty-two year: driving horse gripping and motoring, and Ih n what is called lucky, but 1 had narrow escapes enough to most any man's hair white. Chil- malk d bother me the most, for the poor little thi en't got the sense to Jook out for themselves, and when their parents them out into the street to play nd T have to look out for them, as well as run my car on time, t o s a day's work hard. Over on nd south of Market, where re th 3 all a man can to keep clear of them. From the they can walk until they are four e they seem to have a special lik- r running across the streets; if aight overit wouldn’t likely to turn and run back, or stop on the track and look at the car, and you have to be sure of yourself and the brake and the track to save them. Another thing: Women getting off the car with two or three children lose hold of one some- times and it will go right in front of the car on the next track. That hap- pened to me on Second street the other day. My car came along and there was a four-year-old standing back to me while his mother was going over toward the sidewalk. I stopped about six inches from the child, and the af- fair frightened me so that I Jjust couldn’t move for a moment or so af- terward, but the mother never even thanked me. I've lost twenty-three pounds since I began running on the Mission line, just because I have to work and worry, too. CRONK—I have beennine years cars and have had my share of bad scares. The most trying thing to me is the way men and women step in between two passing cars—a most dangerous thing to do, but they don't seem to realize that fact. People will get off the wrong side of the car in spite of the conductor, and then if another car is coming along there's apt to be trouble. Then, again, there seem to be some persons who deliber- ately expose themselves to danger for a purpose. Some people wouldn't mind getting hurt a little if they could get good pay for it, and most every motor and grip man has met such cranks and had to save them In spite of them- sebves, A motorman’s nerves are strained all the time, with the people, the children and the teams. The heavy truck men of this city, though, are a fine lot o¢ men, the finest T ever came in contact with—they never make any bother if they can help it, but the drivers of light wagons—some of them—are nuis- ances. They like to tantalize a man and keep just ahead of him when he wants to make time. JOHN MILLER—I have worked on five different lines and one of the worst frights I ever got was the first night that I took charge of a motor. It was on Folsom street. near Twentieth, and a child about four years old, who was walking along one side of the street with its neother, saw its father on the other side and started after him. She started so suddenly that I was taken by surprise, and the worst of it was that when she got half way over she fell right across the track. My hair rose right straight up, for it had been raining and the track was slippery, but I managed to bring the car to a Stop within about a hand’'s breadth of her little head. Instead of realizin that 1 had saved the baby's life the father wanted to whip me, which I thought rather ungrateful. but I was new to the business then and had not learned that that's about all we grip and motor men can expect under such circumstances. Down on Second and Bryant not long ago an old gentleman stepped out from behind a loaded truck right on my track, not six feet ahead. I put on the brake like lightning, but as the car stopped it struck him and knocked him down, but didn’t hurt him. The first thing he did when he got his breath was to swear at me for not ringing my gong. I had been ringing the gong for the truck, but if I had stopped to ring it for him he would have been mashed, sure. It was brake or nothing in his case, and so I chose the brake. Broadway and the crossing at Fourth and Mission are the worst two places that I ever struck, and the middle of the day when people are going to lunch, and 5 and 6 in the afternoon, are the worst times in the day. C. F. RACKLIFF—I am a rather new man, but I have had my experienc Two weeks ago T was going down M sfon, near Nineteenth, and in the mid- dle of the block two boys jumped out from behind a car on the other track rieht in front of me. I managed to stop just in time not to hit them, but all the passen;ers were frightened; we had a great time with the women screaming and the men jumping up and shouting. For a wonder they all said that I did well and praised me for my quickness in stopping. On the very next block there was a milk wagon standing in front of a store and the driver jumped in. pulled the wrong rein and turned the horse right on the track, and I had to stop short again. You've got to have your eyes and wits about you all the time, and watch out for everything, and you've got to remember that if you put on the brakes too strong when there's trouble they may break and leave you help- A man mustn't get nervous or excited, no matter what happens, or he can’t do anything. A funny thing hap- pened to me the other day on Kearnr street, near Jackson. A Chinaman & ik, i o e, ~ Vfl'.:“’,a ? ; bl il il 'u with a bundle on his head started across the street and bunted ri-** into the side of my car and knocked,himself over, though 1 was ringing my gong all the time. Talk about absent-mind- edness—he was the most absent-mind- ed person I ever saw. J. D. HELUMS—I have been three years on the cars and I can assure you that it is a very hard life for any one. It is extremely hard on a man's nerves and the excitement and continual strain of eyes and nerves and muscles shorten life as the hardest kind of merely man- ual labor could never do. A motorman’s eye must not be turned off the track be- fore him for more than a second at a time, and he must be ready to meet and conquer difficulties constantly. Night work is the hardest on me, for though there are less people on the street there are more intoxicated ones, and drunken men are apt to do all man- ner of things that make life exciting for a car man. When I was new to the business there was a foggy night—it was New Years, I remember—and a man suddenly appeared right at the side of the track. he stagzered in front as the car was slowing down and got badly cut about the head. The passengers all said that I was not to blame, but it gave me a I put on brakes but shock that it tool. a long while to get over. I think that parents and school teachers ought to teach children to keep out of the streets, and crc at the proper crossings when they cross at all. Wagons, too, are always running into danger. They turn in ahead of us or else cut acri and if we hit one we are blamed. If teamsters and drivers had to be broken in the same as motormen and were not allowed to take teams out until they knew how to drive there wouldn't be half as many acc 2 The worst accident that T was ever in was on the Mission road when a man ran out of a saloon to catch my car., I shouted to him to wait till the up car passed, but he kept right on and wa struck by that car and killed. It was not my fault and I was not blamed, but it unstrung me for quite a while. Motor and grip men are at a disad- vantage for when théy hurt people they . have to stay right there and see it through, but bicyclists and drivers put on speed and get out of the way; how- ever, car men don’t hurt persons for fun or for meanness, though some folks seem to think so. The least little acci- dent that occurs means no end of bother and loss to the men implicated, outside of the ph—sical and mental ef- fects of nervous shocks and strains, so you may be sure that they avoid every- that is avoidable. . LANE—I came near Killing a man down on Kearny street a day or two ago. He was on the car meeting me and his hat blew off and he jumped exactly on my track and feil down. I stopped the car just as the guard was right against him and he got a pretty bad cut on his head. If I hadn’t slowed down for a switch he would have been a dead man, and through not fault of mine or the other motorman, though probably a suit for damages would have followed. That sign “Please do not talk to the motorman’ is one of the best things that the company ever did for our com- fort, for we have to give our entire at- tention to the track and talking is both annoying to us and dangerous to the public ELSON—If the stories of the ac- that happen were told just as MAULTER] * Fuinion Sikeet they occur I don’t think that we should be blamed so much as we are by the public. Now, the other day a little child between 3 and 4 vears of age ran across my track on Folsom street, be- tween Steuart and Spear, and fell flat right in front of me. I managed to stop the car before the wheels reached it, though it was clear under the lattice work, and those who saw the occur- rence or learned the facts from eye-wit- nesses praised me for my coolness and quickness. Two reporters, however, got on the car and wanted me to break the rules and talk to them about it, and because I would not they said very wrong and unkind things of me the next day, and made me feel very badly, for I wouldn't have hurt the baby for the world, and even coming near doing S0 gave me a great shock. L. SWEETMAN—If people would wait till the car stops before they get on or off it would be a great deal better for all concerned, but it is a general practice to jump on and off before a car 1s under control,and if anythinghappens the blame is laid on the motorman. We are not clairvoyants, any of us, and it is hard to tell by the looks of folks what they are intending to do. Take, for instance, what happened to me on Bryant street not long since. A man sitting on the front end wanted to get off at Fifteenth and he got up and stood on the forward end of the step and then, not waiting for the car to stop, swung himself off in such a way that he fell right in front of it. It was a wonder that he wasn't killed, and casesalmost as bad happen right along. Men and women both persist in get- ting off the wrong side of the car, and getting off and running around in front of the car just as it is starting up again, to get across the street. If they happen to be short the first we know of them is seing their hats just in front of us through the window, and it gives a fellow a pretty hard start, too. Then women have a way, down in the busy parts of the town, of getting out into the middle of the street right between the tracks when they want to take a car, and that is taking chances that they ought not, and some people seem possessed to promenade on curves. I've seen dozens snatched back by other persons just as a car was coming around, and they never seem to realize what they escaped. W. J. WAITES—During the nine years that I have been on a car I have seen accidents nearly happen almost every day through simple carelessness or recklessness of pedestrians and driv- ers. Children are continually running into danger and keep us car men on the jump. One of my frights was when two boys on Mission street. near Six- teenth, started to chase each other across the street. T was going not over seven miles and rang my gong as hard as I could, thinking to turn them back, but they paid no attention. The first one got over the track all right, then turned and came back, and though he saw me he seemed to get confused and ran right toward me. I turned cold, for I have children of my own, and couldn’t bear the thoughts of hurting one, but I knew that it wouldn't do to lose my head. I remember of deliberately count- ing in my head the notches of the con- troller “one, two, three, four,” so as to make a good stop, and though the little fellow was knocked down and his head was under the pilot board, he was not hurt at all to speak of, only frightened and dusty, and I tell you I was thank- fui! I am the man that ran into that laundry wagon over on Alabama and Twenty-sixth streets—that is, I didn't run into it, but I came so near it that there was only a matter of four feet be- tween me and the four children who were driving it. We have to look out particularly for such wagons anyhow, for the drivers are so walled in that they don’t look out for them-elves very well, and so I slowed down when I saw it coming, but they had the horse go- ing at such a good pace that when they pulled the wrong rein and the car and one of the wheels came in contact the whole outfit went over. The car didn’t touch one of the children, but one of the papers had it that all four were crushed under the pilot, and that it was all my fault, but it was more interest- ing to tell it that way than to state the honest facts. J. H. DUKELOW-—We all have about the same trials I guess—children play- ing in the street, people welking along meditating when they ought to have their eyes and ears in active service, persons getting off the wrong side of cars right under our wheels almost, ana careless or ignorant drivers. To see the small boys that are allowed to drive wagons here is astonishing. If they can sit on a seat and hold reins they are given charge of all sorts of rigs, and though thev may do well enough when there is nothing to frighten them, if they see a car coming or get into a tight place, they are just as apt to pull the wrong rein as the other, and bring their horse and themselves right across the front of a car. Grown persons who are not accustomed to driving do the same thing, too, and when we run into them we are the ones that are blamed. Then there are persons who think it smart to annoy and alarm us and some will deliberately walk out in front of a car for that purpose, and laugh at us when we slow down. Hardly a week passes that I don't get a dead fright over children, and it does seem to me that parents and guardlans ought to be made to keep their charges out of the middle of the street. Children stealing rides and playing tag off the pavements risk their lives daily, and the ones who don’t teach them better ought to have some of the blame when they get run over. Night runs are bad for there are so many intoxicated peo- ple and you never know what they are going to do. Down on Third street not long ago a man came out of the shadow and 1 thought he was going to board the car. Before I could stop, though, he walked right in front of me and the car struck him. I heard the bump and it frightened me terribly, but as I had slowed down on seeing him it only knocked him over. For a wonder he said it was his own fault, for he had been drinking and didn’t know what he was doing, but that didn’t make the shock to my nerves any le J. S. BUCK—I came very near being killed myself over on Broadway last summer. There were a lot of boxes stacked up on the edge of the sidewalk and a boy ran right out from behind them across my track. I couldn’t stop the car, to save me, until it hit him and rolled him over, and though he was only hurt a little a big crowd gath- ered and wanted to hang me right there. One man pulled a knife, and altogether 1 had a narrow chance of it. You see, people’s sympathies are al- ways with the one who gets knocked down or hurt by the car; they never stop to think out the motorman’s side of the affair, and so it is a rare thing when we car men get fair play in these matters. A. E. OSGOOD—If the public were half as careful of themselves as the railroad men are of them there wouldn't be any accidents at all comparatively. I don’t believe that there’s a man on the lines who would hit a dog with a car purposely, much less a human be- ing. We are on the lookout to avoid trouble all the time, but there iIs hard- 1y one of us who hasn’t had adventures with reckless or careless persons on foot or in teams, that just make us sick with fright for the time being. Rainy days, when the track is slip- pery, and fogey days, when you can't see clear before you, are times we specially dread, and children running in the street and newsboys jumping on and off cars, and sometimes trying to jump from one car to another as they . make our trips particularly ex- nRNNRN nuuNNNN F vou go along Sutter street till you come to No. 639 you see a brown house standing back from the street. It bears the sign, “San Francisco Fruit and Flower Mis- sion.” Years ago some girls wantéd to help those who had less than they them- selves, so they formed themselves into a society to visit and read to the sick to brighten their shut-in lives rs and fruit. The work grew. Now the name I8 most misleading. At the Congress of Charities the work of caring for the glck of all the societies was given to the Fruit and Flower Mission, each so- ciety contributing a certain amount toward the expense. Mrs. Buckingham, the vice-presi- dent, had asked me to meet her at the Thursday morning meeting of the so- cf The ladies were discussing ways and means and fllling baskets with groceries to carry to their charges. Those who were able to come or send were there, waiting for their weekly supply One pretty little girl came in timidly. “I was to come here this rorning.” “Yes, Indeed- that's all right. What ur name?" Mary Wilson.” The list was consulted and a basket given to her. “This is for you.” She looked at it, then at the giver, and back to the basket. “But this is enough for lots!" “Yes, that is to last for a week. Don’t you understand? “Oh, something to eat every single day! To-1..0rTOW, too?” She was not accustomed to three meals a day every day in the week. and t with flo is The mission is absolutely non-sec- tarian. The workers are Jewish, Cath- olic, Protestant, Theosophist. .hey have never clashed and there are no dis- a fashionable society and works both ways. Those who give are edu- cated in life as it is as well as those who receive. Two trained nurses are employed to do the work where skill and training is necessary. Also they teach those they visit how to take care of themselves, their children and their homes. I went with one of the nurses on her rounds. “Promise not to say any- thing about me. I should be ashamed. nnuLLLuLLw 2% HOW “SHUT-IN" LIVES ARE HELPED By the Fruit and Flower Mission. I am paid for the work, and I do love it s0,” she said. They are supposed to work from 8 to 5, but they leave off work when they can, and it may be any hour of the night. The hills are steep and cars do not go everywhere and money is scarce. Sometimes the work is very discour- aging, but almost every place the nurse’'s patients love her and look for her coming arnd try so hard to do as she asks them. The nurses are subject to call at night, for sick ones may grow worse, or they may be called to recelve a small newcomer. An old woman lay in her room alone for two months. The neignb.r3 came in when they could and he!ped her, but the women of the poor have so much of their own to do. It was oniy the second visit of the nurse, and she had not fully gained the confidence of her patient. It takes sometimes many vis- its to galn any response, but usually it is immediately given. ““You do not want all these things on g‘{m'r_- bed, let me make you comforta- ble. “I can’t get up; maybe nobody will come in; I can reach them here.” “I'll put everything back, and see, T've brourht you some clean sheets and pillow cases and a nightgown; won't you let me put them on?" “I always did everything for myself; I do not like to be a bother.” “But I love to do it. You will let me rub your back; it must ache lying so long in bed.” The eyes gave half consent, for though the old lady said she felt pretty well, she was in an advanced state of consumption, and also she had a can- cer. No precaution had been taken to prevent the spread of either contagion. It was a joy to see the transforma- tion, how deftly that linen was changed and the patient gratitude of the suf- fering old face. She drew the line off sharp at water, however, “Now I comb my hair.” “Let me do it, you are tired already.” “No, no, no one ever combed my hair since my mother.” The room was so dirty, but some bits of beautiful Mexican embroidery, pie- tures and books, plants and ‘the pains- taking contrivances to keep house in one room showed that she had been very cozy and comfortable. The dirt worried her, and it troubled her that strangers should have to wait on her. “I always liked it nice, but now it makes me so sick when T sit up.” “Of course it does. You have always worked for others, so that is why we love to help you now." On a chair drawn close to the bed was a small oil stove where the old lady did her cooking. New supplies were with- in reach on a table and on the bed BRRRRRRIRRUUNNNNS LEEEEELE | | LR R AR AR AR AR AR AN R AR AR R R R R R R AR AR AR A were books, papers and some mending. Only a poor old woman, whose chil- dren were all dead, and her husband, too, waiting a while till she, too, went beyond. In the next place we visited there had been a pathetic attempt to clean up. The morning work, however, was un- touched, the dishes unwashed and bed unmade. A ragged woman, unkempt, sat in a low chair rocking a baby and singing the most beautiful music I ever heard, so familiar, but a new meaning given to the old, old words. She had sung in the choir and because she preferred the English had adopted it in place of the Latin. “We therefore pray thee, help thy servants whom thou has redeemed with thy precious blood.” The baby lay quiet, a girl with yellow curls and big brown eyes fastened on her mother, and drinking in every strain of the music. The room was full of sunshine, and standing at the door we forgot that we were there to help. “No, she seems in such pain and she cries when I stop singing.” The little one rolled {ts eyes at us, but the intelli- gence had gon: out of the face, for it was “not all there,” as the Scotch kindliness puts it. Nurse took the little one so tenderly. “How is Ellle?” “Bye, bye."” “You shall go bye bye, but now I must dress that burn. Ellie be good girl?" She hegan to tremble as the clothing was taken off. The mother brought a basin of water and some clothes. She held the child, kissing its hands while it screamed with the pain and fright. It had fallen against the stove, and the hands, arms and one side were fright- fully burned, but with the careful, skillful dressing given daily it was get- ting on beautifully. “I am so proud of Ellie, and her mother, too.” From the porch came a drunken voice: “Mother of God, where are ye, ye shaming, weak-kneed child of— “It’s only amusing myself I was, beg parding.” “Ellen, you are drunk; go home and g0 to bed.” “Ye lie, and may it choke ve where ye stand. Take shame upon ye, to come here meddling with decent folk.” llen, go home.” Home is it, ye say; it’s no home of yours I'm in—eit clear you, I'm going to bed here.” “No, you are not; you are going home.” The woman’s tangled red hair and bloated face told a tale of a long beut. She began cursing us in the most hor- rible language; the baby screamed and fear and shame. I came out of my trance and took the woman by the shoulders and helped her out. “Now,” said the nurs 'm going to take baby for a little walk. You go get the dishes washed and I will help you clean up. You know it is pretty dirty here to-day, and you do not want your husband to come home and find it this way, do you?" “Baby fretted so.” “I know; I'm not scolding you. You |are going 'to learn to plan_ and then | things will go easier. I've been taught | how, you know, and I'm going teach you, am I not, dearie?” “I do want to try. I am to Mike—him as does so much.” “Yes, you are; he wouldn't change you for any one.” While the nurse was gone the mother talked to me. “Ye know, I was a factory girl. and when Mike married me he was doin’ well and could hire a woman now and agaln to do things, but now the hard times he can’t. He got me a sewing machine, but I can’t sew. I'm going to learn, though. That blessed nurse is teaching me everything, and me so slow.” Up a hill next and into a cigarette factory. A boy, sick, deformed, only half liv- ing, sat watching a Chinaman rolling cigarettes. He himself rolled ¢ne occa- sionally, but he was too weak, and a bad finger hindered. It was bound in a dirty bandage. His eves brightened at sight of the nurse, but at me they looked coldly. “How are asked, kindly. “Pretty -well.” you to-day, Joe?” she “Has your side been dressed to- day NS “Shall T do it?” ; A young woman limped into the room. She was not glad to see us. Her mother was asleep. No, we could not see her. She must get dinner ready for her mother. No; she could dress the boy herself.” “Nurse wants to do it.” “May I do it if I come back after you have had your dinner?” said nurse. “Yes, if you want to; myself.” We went away and got some lunch ourselves, for it was past noon. “] want you to see that place,” said the nurse. ‘“We have tried every way to get it closed. Dr. Sherman made a formal complaint to- the Board of Health. Dr. D. has done the same. Miss Fisher, the president of the mis- sion, has reported it. I have reported it. But nothing has come of all the complaints and reporting.” The cigarettes are made, and a good many must be sold to pay the rent ($15) and feed and clothe that fdmily. It is a question, for the cigarette-making is their means of . livelihood, yet every cigarette that goes out of that partic- ular shop is laden with disease. We went to the place again, and in all the slums of New York or Chicago never did I see anything to compare but I can do it its mother seemed bewildered between with it. HELEN GREY. to | It isn’t much use | the | snnLuRNRRNuy WAS a Seventh Ward born in the very heart of William M. Tweed’s old district, and I passed my childhood in the happy- go-lucky fashion characteristic of the small boys of that section of old New York. I don’t remember much about those days now, so much has in- tervened between them and the pres- ent, but I don’t think that I was dif- ferent from my companions except per- | haps in being a little more go-ahead and boyishly mischievous than some of | them. At that time every boy in that ward avas ambitious to be a printer, since | printers received excellent wages and it was thought, besides, to be a grand thing to understand all about that es- pecial business, so as soon as I was anywhere large enough to attempt such a job I began to work at feeding presses and such employment and made quite a bit -of money at it, too. By and by, though, I found this | rather monotonous and made my way to the docks, where I learned to calk vessels as well as veterans at the and some way being among the | ships and around the wharves so much | and hearing sailors’ yarns and travel- ers’ tales by the score, made me feel very dissatisfied with my humdrum ex- | istence right there in the city of my birth. | I was naturally of an adventurous | disposition, fond of fun, excitement and | change, and pretty stout-hearted with it all, so one dav I made up my mind | to strike out for myself and see a little | of the world beyond New York harbor. | A few hours after I made this mo- mentous resolution in my young mind I was on board a ship sailing gayly past Sandy Hook on my way to the | Pacific Coast, and as I worked my pass- age 1 didn’'t have time to be home- sick during the whole voyage, I found plenty of employment at my trade ,of calking here in San Fran- cisco and worked all around the water front from Rincon Point out. I worked up at Mare Island, too, for a time, but mostly here in the city, where I made a good many friends among the lads of my own age. My boarding place was over in what we called “the Val- ley” then—it is known as “Tar Flat" now—and a lot of us young fellows formed a sort of a club and hired a room in which to pass our evenings together, and it was there that I first began to string verses together ana sing them to popular airs of the day. The boys liked my songs immensely and thought a good deal of me because 1 was always willing to sing and gen- erally had something new and fresh on hand to amuse them, but I had no RRUURRAVRUUAREIVUIRLLIRINERILRINS : HOW | BECAME AN ACTOR AND AUTHOR. By Edward Harrigan. suLLuuIRLLLRLRLRLLLNLLNLN voungster, | thought of making my living through | gor, Me., to San Francisco and had anything of that kind until the calk- | ers’ strike came on and 1 found my- | self thrown out of employment. Then any sort of an honest job was wel- come and when 1 was otfered a small salary to go on and sing one of my | songs at the Olympic Theater, down | on Kearny street, where the California | Exchange now is, 1 decided to try it, | and the result was that 1 never went | back to ship-calking again. All the boys that 1 knew came that first night and brought all the boys that they knew and all that their | friends knew and they handed me bou- | quets of raveled oakum over the foot- lights and made things lively generally; it was all done in a spirit of friendship, though, and the ) 't that I made was so pronounced that I kept right on in the | business. Alex O'Brien wes my first team-mate and he and I played at the Olympic and at the old, and afterward the new, Bella Union, doing Llack-face special- ties under the name of Harrigan and | O'Brien. After that I took up Irish business with a man named Rickey, and we brought out “Mulcahy’s Twins" and others of my original sl -tches at the Pacific Melodeon on the corner of | Kearny and Jackson streets, and played under d:“erent managements in other towns. Making a success of our acts here | Rickey and I and a clever minstrel and farce actor named Otto Burbank went to Chicago, where we appeared at the Winter Garden. then badly run down, and pulled the place up to most excel- lent business. It was in Chicago that I first met Tony Hart, then a very wndsome, talented boy and a lovely singer, es- pecially of ballads, which he had been singing with the Arlingti 1 Minstrels, then closed. I got him a position with us at the Garden and wrote a sketch, “The Little Fraud,” for him and my- self, in which he took the part of a young German girl. Without any ex- ception Tony Hart was the best female impersonator that I ever saw, and one of the greatest of character actors, and together we did a phenomenal business. I wrote our songs and sketches and plays, aiming always at true delinea- tions of character, combined with wholesome humor, with occasionally a touch of pathos, and we made a hit wherever we went. We played “The Little Fraud” for one hundred nights in the Howard Athenaeum of Boston, under John Stet- son’s management, and then spread out on broader lines. In New York we played at Butler's, Tony Pastor’s, Josh Hart's and other places, and then I combined a number of our specialties, stringing them together with a thread of plot and calling the whole ‘“The Doyle Brothers” we took it from Ban- nuR nuRRVRUKS 22888 ks (R RR R good houses all along the line. Coming back to New York we leased the Theater Comique, where we struggled along for a year, paying eXe penses but making nothing because the house had been run down by Matt Mor- gan, one of the greatest scenic artists and cartoonists that this country ever produced, who ruined himself by orig- inating and producing “living pictures” twenty years before his time. His en- tertainments, which were artistically magnificent, were stigmatized as “vul- gar” by the public, who years after paid out small fortunes to persons who utilized his idea in a much less refined and pleasing way. At his old place I began my series of ‘‘Mulligan” plavs, ten in number, pro- ducing them as sketches at first and then amplifying them into three- act plays, making the charac- ters striking types of the peopls in the lower wards of the city, and I followed these by dramas— “Pete,” “Waddy Googan,” “Old Laven- der” and others. Prospering well, we built Harrigan and Hart's New Thea- ter Comique and presented there all my own plays, including “The Major,” “Squatter Sovereigntv.” “The Black- bird,” “McSorl: Inflation,” “Investi- gation,” and so on, and in the height of our success the theater burned down uninsured and put an end to it all. After that Hart and I separated and I took the old Aquarium for a time, but was forced to build again for the reason that my success was such that I was the prey of landlords who wanted ex- orbitant rents from me. I built Harri- gan’s, now the Garrick Theater, which is Mrs. Harrigan's property, and still the daintiest and prettiest of the city theaters, and played there for a time with my son, Edward. After his death, at the age of 18, we leased the place, as I had become convinced that the actor- manager—with the exception of Augus- tin Daly, that most indefatigable and successful worker—has little chance in competition with the purely business or speculative manager. —e——————— ‘When the Methodist conference at Law- rence, Kans., was almost ready to close some of the ministers were discusing the appointments and agreed among them- selves that everything was coming out satisfactorily, the appointments having all been fixed up. Then another preacher bade his brethren not to be too sure. “For,” sald he, “I was in conference with Bishop Fowler once and we fixed every- thing up, and then the Bishop asked to be allowed to commune with God awhile. The rest of us retired, and from the con- dition in which we found the appoint- ments when we came back, I should say that, if the Bishop talks with God again to-day, he is likely to break that slate of ours Into pieces so small we can't wtite our names on 'em."”