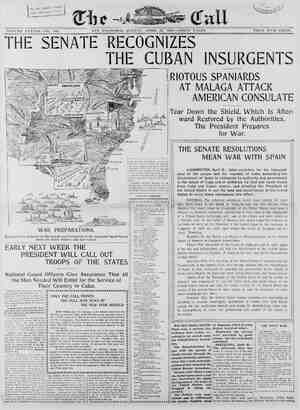

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, April 17, 1898, Page 18

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

18 THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, APRIL 17, 1898. MAKING GIANT WHR GUNS Thousands of Men in the Red Glare of the Fur- naces Turning Out Steel Tubes That Shoot Fifteen Miles. Will days of preparation for war the Washington navy-yard is one of the most interesting spots to be found anywhere. Strictly speak- ing, it is not a nav; rd at all, but a gun factory. Here it is that all vy guns and most of the light nd boat guns for the navy arc built. The amount of work done in this great national factory is enormous, even in times of peace, but now that the lathes, engines and tools are run- ning at full speed twenty-four hours out of twenty-four, the number of guns and gun carriages turned out is near- ly trebled. Passing through the gate with its trim marine sentry pacing to and fro, the visitor sees uniformed officers has- tening this way and that, bi with their duties, and hears on e side the dull rumble of machinery, the heavy thud of the triphammer, and the snorting of the am cranes. A small army of aftsmen in the offices are busily preparing plans and drawings for the use of the gun builders, and the civilian bosses and foremen of the shops wvhere keeping watch with eagle ey Theirs 1s a most re- sponsible duty, for any careless and in- competent workman with a single slip of his tool might spoil a gun or car- riage which had cost the Government thousands of dollars to put together. The putting together or ‘“‘assembling” of a modern gun apparently a simple matter. But it is really one of the most delicate operations in the world. The greatest care and precision are neces- cary to make the different parts exactly fit, and on: revolution too many of a plane or boring tool would injure the part beyond repair. Hence comes much of the fascinati n in watching the con- structi of one of the big guns as it grows in ma ve and polished beauty ready to take its place on one of our men-of-war. First of all the tube of the piece comes to the factory from one of the big steel companies, the Bethlehem or the Midvale, which have the contracts h zings. The tube comes in to furni g h with only a core bored out. the rou and looks like a heavy piece of steel pipe. For the four-inch guns it is 13 feet 7 inches long, while for the 13-inc guns it attains a length of 40 feet. This tube forms a basis for all “uture opera- tions. A modern gun is built up by slip- ping upon it a number of jackets and | ind shrinking them to a perfect A -inch gun when fin- separate and dis- b assembled fraction of an tinet and fitted to the minute inch. As the caliber and size of the gun diminishes the number of parts is reduced, and the four-inch piece is composed of only five. In building up the gun the rough tube and the bands are first placed in lathes and c fu planed down to the di- mensions required. The diameter of the interior of the cket which is to slip over the tube half way its length must correspond with mathematical ex- actness to the diameter the tube's exterior; while the hoops, which in turn fit over this et, must be treated with a like pr ion. This work of planing is done*in the great north gun shop, as it is known at | the navy d, and when it is com- pleted, the tube and the bands have to be carried to the “shrinking pit” at the north end of the shop, where the next | process is to be undergone. three heavy traveling cranes in the shop, of 110, 40 and 15 tons lifting | power, respectively, and they pick | up the huge pieces of iron and carry | them to their destination as easily and | lightly as if they weighed nothing at all. The “shrinking pit” sunk in the floor of the at each end with an oven. in which the bands are to be expanded | until they can slip over the gun tube, are heated by an air and oil blast to a | temperature of 700 degrees Fahrenheit, | for this degree of heat is necessary to | expand the heavy jacket for the 12 and | 13-inch guns. At the pit the tube is planted carefully on end close to the oven, in which is being heated the jacket that it is to receive. Pipes are | s0 arranged that a stream of water can be run continuously through the core | is a deep hole | hop, and fitted | These ovens, | of the tube, to keep it cool and prevent expansi slips ov n by the heat, as the hot jacket r it When 2all is ready, the men who are to perform the delicate task stand at attention. Each one of them has his own particular duty, and they are trained to act in concert, like a com- pany of soldiers. The jacket has been | placed in the oven and sealed up, to await expansion by the heat. The fore- man gives the word, the traveling crane comes up and lifts off the hot lid of the oven, exposing the jacket within, the hooks are made fast to a clamp pre- viously attached to the jacket, and the heated mass is lifted carefully from its flery bed. The engineer of the crane watches, e sl Hlke feyer e HIENals oL ihe foreman belotw, and when a sufficient height has been reached the jack-t is swung over the tube and lowered. Men with immense canvas mitten guide it as it ¢ down and adjust it in place. When it has been slipped - ver the tube streams of water are turned on to cool it. As it cools it shrinks back to its original size, and the delicate operation is complete. Strange as it may seem, after coming through its fiery ordeal thz jacket hardly shows a sign of heat as it is lifted from the oven. There is a slight bluish tinge, and that is the cnly thing to distinguish it from the cold jacket which went in. The exterior ol the tube and the interior of the jacket being ex- actly the same size, only the slightest expansion is r quired to make one slip over the “Mer. From 3-100 to 5-100 of an inch is all that is allowed, even in the monster 13-i»-h guns. So the speed- iest and most accurate work is neces- sary after the jacke: leaves th. oven, for if the iron should cool off before it was in vlace it would clamp at once upon the tube, and the gun would be ruined. A similar process is gone through with in slipping the smaller hoops over the jacket. The shrinking of one part on another makes an absolutely perfect weld, and after once the band is in place nothing short of chipping it off piece by piece would remove it. The shrinking of the different bands of the piece having been finished, it is again put in the lathe and turned down to the required size, ana the edges of the bands are beveled oft to give it a neat appearance. It is then ready for the delicate operation of ri- fling. Only the most experienced mechanics in the shops are in charge of the rifling machines, for on the perfection with which they perform their work the whole utility of the gun depends. The auger which cuts the grooves is care- fully adjusted and lubricated, and the little hard steel chisels fitted on a long beam which runs through the bore of the gun commence their work. Only the smallest fraction of an inch is taken off at a time, and the greatest care is re- quired in adjusting the auger exactly. When once put in position the lathe doee the rest of the work by slowly There are | | inches c.libe turning the gun as the tool eats its way through. After being rifled the gun is placed on a car and carried to the breech ma- chanism shop, where the interrupted screw breech block, in use in early all the navies of the world, is fitted. The carriage with its recoil cylinders for taking up the “kick” of the piece when fired, having been finished in the naval ge shop with as conscientious care as the gun itself, the gun is put together and shipped on the barge down the Potomac River to Indian Head, to be tested. The guns built at the Washington navy yard are recognized as the Ziost perfect and powerful specimens of na- val ordnance in the world, and the weight of their powder charge and pro- jectile, their length ard thei. penetra- tion would have been considered out- side the bounds - reason thirty years ago. The length of a 13-inch breech- loading rifle is forty feet; its weight sixty ‘and one-half tons; it carries a projectile weirhing 1100 pounds—more than half a ton—which can penetrate 23.42 inches thick at a distance of | s. It has a velocity at the )0 feet a second, and a ve- | of 1805 fe-- at a distance of 2500 | muzzle of yards, which is produced by the explo- | sion of 550 pounds: of br prismatic | uowder, each grain of which is oc- | tagonal in shzne and molded to an ex- | act size. The cost of each discharge is ab $1500. The range of a gun of thir is about thirteen miles, | or a mile to,each inch, which is the ap- | proximate range of all guns. A 13-inch | gun is built to fire 250 shots before it | loses its temper and becor.es useless, | except for old iron; but in most cases many more could probably be fired. | The 1100-pound projectile is almost as | carefully made as the gun. It is of hard | teel, with an armor piercing point and | s fitted with copper band: which take | 3 rifling, and being of soft injure the delicate | of which there are fifty-two. | monster cannon the vard produces small | fire ordnance of the Fletcher, | Maxim, Driggs-Schroeder and Hotch- | t¥pes, which are used aboard ship | zainst torpedo boats, nd for boat service. | much simpler in | avy ord- are their construction than the h | nance, but the same great care and | These weapons | thoroughness of workmanship charac- | | terize thelr building as the heavy ord- | nance. Six weeks is practically the minimum of time for the making of a modern gun, and to finish one within that space everything would have to go on mar- | velously well. The “treatment” of the steel would have to be a success at the very first attempt—something that does not often happen—and the first tests would have to show that the Gov- ernment standard had been reached. | Oftener than otherwise these results | | can only be obtained through much try- ing and the expenditure of time. A | batch of guns may thus take months in the making, while good luck may bring it down to weeks. It is in the casting shop, of course, that the process of gun making hes its | very beginning, in the furnace where steel is made from a medley of pieces | of old iron, pig iron lengths, | bits and odds and ends of castings, long since relegated to the scrap yards. Here is the first stage of the modern gun—ragged and rusty metal that is carted in wheelbarrows up to the fur- nace doors. The maws of blazing heat, several thousand degrees in intensity stands open to receive it. So over whelming is this heat that even the master melter has to put on blue glasses to peer into the flames rising over the bubbling sea of metal when the doors are open. is only revealed a single spot of bright- ness, an eye that Jooks into the fur- nace’s flame, and even this cannot be approached too closely with the naked eye. The gun is under way. metal are already Ten tons of in the furnace—a by banks of sand. Other things steel are to be made of this mass, the gun works being only a portion of the plant. Whether used for peace or war, steel is steel, differing only in qual- ity. It is all “boiled down” in the same way. In shadow is the casting shop, except of light, a wave of extreme heat, thrown out. In the dusk of shadows grimy men raise the sea of metal with long bars. The master mel- ter, never still, steps now and then to his wheels, set at one side of the fur- nace and looking like the brake wheels on a freight car, and gives one or the other a sharp twist. By this he regu- lates his fire—five hundred degrees at a twist. The silica bricks with which the furnace is lined can stand four is broken | ‘When the doors | are dropped down—that is, shut—there | lake of molten, seething metal held in | of | when the doors are raised, when a flood | the | | thousand degrees of heat and more be- fore they commence to melt. The mas- | ter melter runs up the heat to the ex- | treme point and then lets it down. There are three “heats” a day in the | casting shop. Three times metal is heated, three times it is let go with a | mighty rush into the casting pot. The last few moments of each heat are the dramatic instants. Tt is then, at the judgment of the master melter, that the furnace is fed with ‘medicine,” FORGING shovelfuls and blocks of metal being tossed in. On this depends the qual- ity, the strength, the elasticity of the steel, essentials of the most vast im- portance of the gun of to-day. Two hours is usually sufficient for the boiling of this steel in its cradle of sand. At last the one moment ar- rives. The bar at the furnace's back is worked through the sand to make an opening. An instant, and into the casting pot below the ma | tering millions of sparks, a glowing, golden torrent that foams and hisses as it plunges down. The picture of the gun's second stage is superb. On every hand fly these sparks, and the mass bubbles and seethes in the casting pot. On its top, | through the glow, can be seen a dirty | mass—the slag or the scum that is of | no use or value. But the picturesque- | ness of the scene has not ended. The casting process is only half through. | The liquid metal must get into its molds, and that in short order. On a track the casting pot rests. It | is pushed along this track until a gi- | gantic crane overhead seizes it, swing- ing it aloft. Over mounds of sand it is swung, and the metal, by the move- | ment of a bar, is allowed to drop down | in a thin stream. Again shower upon shower of sparks, surrounding the men who, with chains and staves, control | the clumsy pot and pull along the | crane. The grim old shop, with its floor of sand, its unrelenting dust and its dreariness, is made into a brilliant cavern for the moment, and the toil- | ing men are supernatural in the light. | A prosaic time follows, when the | metal in the molds must cool. When | the sand is finally knocked away the gun that is to be is only a rough mass of cast steel, indicating only to the expert its fine quality, and not even to him in any degree, for the tests must come to prove that. In the forg- ing shop this mass is hammered and worked until it becomes an octagonal ingot of just twice the weight it will possess when it is finally turned and bored into a “jacket” or “tube.” The hoops, the third vart of a gun, are cast and forged hollow, not in solid cylinders, as the jacket and tubes are. With the carrying away of the rough ingot of steel from the forging. shop the special work of gun making com- s runs, scat- | tory is the scene of the first step in this process. Completed guns, ready for mounting and for fire, are not turned out in thess gun shops. The finishing touches, the actual putting together of the parts of the gun, the rifling itself, are done at the ordnance works ig Washington. It is the business alone ®f & gun shop to make the steel and to hand over to the army and the navy the three parts of a-great gun—the “‘tube,” the “jacket™ (which is slipped on over the tube and then “shrunk on” by contraction) ana the “hoops,” two in number, which, for the purpose of strengthening, are fittea ?nbtighuy over the muzzle end of the ubes. HOW NATIONS DECLARE WAR. OTWITHSTANDING the fact that most people consider a for- mal declaration of war necessa- ry before active measures can be taken it is usually the case in these go-ahead times that no warning whatever is given. When Rome was mistress of the world a declaration of war was a sol- emn function, attended with so much | ceremony that a special collere of her- alds was always kept in readiness to perform ‘it when necessary. In me- dieval times letters of defiance served to give warning of hostile intentions, and still later heralds were sent to throw down the gantlet and make a verbal declaration of war In such times formal declarations were necessary to differentiate between the private br 1s of a fagv barons-and a national war for avhich the commu- nity was responsiblc. but at the pres- ent day total concealment as long as possiblé is the most universal rule. The objects, says the writer In Tid-Bits, of this are usuallv either to anticipate the designs of some other power, to avoid the onus of admitting a state of L o e e s e e BIG GUNS FOR THE ARMY AND NAVY. mences. The horing and turning fac- war as long as possible, or to gain time by swiftness of attaclk. The latest instances of formal decla- ration by herald were in 1635, when Louis XIII sent a herald to declare war against Spain, and in 1657 when Sweden declared - r against Denmark by herald sent to Copenhagen; while as late as 1671 war between England and Holland was declared by solemn proc- lamation. As the most recent cases are those likely to influence the conduct of na- tions in the immediate future, the wars of the present century are of the great- est interest at the present crisis. y :, e At In the quarrel between Russia and Turkey “which immediately preceded the Crimean War, a formal declaration was issued at Moscow by proclamation of the Czar, and three days later, after the Turks were well aware of the state of affairs, operations were commenced | in_earnest. In the less consideration was shown. was formally declared by Britain on March 22, 1854, and on the it was proclaimed by the High Sheriff of Lon- don from the steps of the Exchange. But these declarations were made merely to justify the step to the peo- ple and to ask for their approval and help. Before that.time active opera- tions had commenced by the entry of the British and French fleets into the Dardanelles, contrary to treaty, and the forced retreat of the Ru n fleet to Sebastopol when the allies reached the Black Sea. On February 8 the Russian Minister was withdrawn from London, and the British and French Ministers from Petersburg. Although such a step u ually precedes war, and is often regard- ed as equivalent to a declaration, it only signifies that all hope of successful dip- lomatic negotiation has been abandoned and that war is likely to ensue. It does not necessarily imply a state of war, such a ate requiring some definite act of hostility. n the opium war of 1840, the Ttalian Wi of 1847 and 1849, the Anglo-Persian war of 1856, the wars between Austria and France in 1 Prussia and Schles- wig-Holstein in 1863 and Brazil and Uruguay in 1864, various hostile acts were committed before any declaration of war was made, although in some cases manifestoes were issued to neu- tral powers. In the Austro-Italian war of 1859, the Austro-Prussian war of 1866 and the Russo-Turkish war of 1877 the declaration and active operations were practically synonymous. In the last mentioned case, for example, the Porte received a cor+of the declaration on the evening of April 24, the very day on which 50,000 Russian troops crossed the Roumani frontier. The most notable instance in the pres- ent century of a formal declaration of war being made before actual opera- cases of Britain and France | War | | tions were Franco-Pruss | case declaration | £c the French, whe it voted la. war credits « wing day th r returned to Pa A | formal intimation of hostile intentions was then sent to Berlin and laid before the Parliament of the rth German Confederation on July 20. On November 12, 1885, Britain was honored by a declaration of war from King Theebaw of Burmah, but it was a needless formality on the part of his dusky Majesty, for the British troops were already on the way to his capital, and the only reply to his challenge was his deposition, which immediatel sued. THE ORLOFF DIAMOND. At the beginning of the eighteenth century a soldier belonging to one of the French garrisons in India became enamored of the s of Brahma in the Temple of the Serringham. These eyes were diamonds, more brilliant than ever shone under the eyebrows of Crapaud’s European divinities. Their luster captiv is soul. He haunt- ed the temple a ding to the might of the god became a convert to his wo! ip. At least so he persuaded the pri who went so far as to admit him to some care of the temple, doubt- less trusting Brahma to protect h a stormy night the con- the other having re efforts to dislodge it. Brahma as left squinting, and the perfidious Frenchman sold his prize to a captain in the English navy for about $10,000. 5 Later it was bought by the Armenian merchant Schaffras for more than five times thi s shown by him to Cath: who offered for it about $400,0( a life pension of $18,000 and a patent of nobility. Schaffras re- fused this offer and subsequently sold the diamond to Gregory Orloff for the um, without the patent of nobil- Orloff, part author of Catharine’s greatne: and raised by her to the steps of the throne. A BIG GUN AFTER IT IS CAST AND MOUNTED