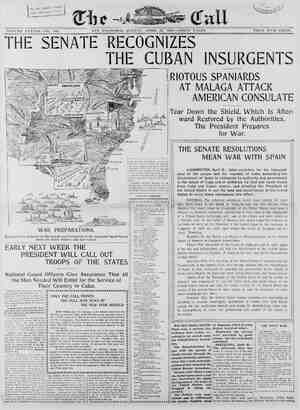

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, April 17, 1898, Page 19

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, APRIL 17, 1898, 19 DISGUISED HERSELF IN MAN'S CLOTHING TO EARN HER LIVING. aac o < V¥ W= S N b Strange Story of a Young Woman Who Wbrked in Sf¢ DISAPPEARING FROM THE WORLD AS A WOMAN. a Photograph Gallery on Market Street. ‘At first 1 was scared half to death every time a man came near me, but no one seem:d to suspect me, and after a while I began to feel comfortable. At the outcome I found that it is best not to try and be az imitation of the opposite sex.” ficgegeRegegegeRRoRaF oy oFoR R FoR Re ] ks ¥ ERE is the story woman who laid aside her skirts, & 3 disguised herself in men’s clothes and worked among men daily & 5 for months without any one suspecting her sex. f=3 5 She adopted the disguise because she thought she could k=3 o earn a nd live cheaper. Now she thinks different. o > or montl name of John Warden, Miss Warren li & . 1 ong men in the ordinary duties of business i Fowzer's photograph gallery, where she worked as a re. = st ed Miss Warren as a “good fellow”; she was very popu- bod ¥ all her acquaintances outside of the gallery. o ¥ One day the boys got up a theater party and invited John Warden, 2 ¥ C t want to go because she knew that to go meant to drink a < ¥ of beer, and she disliked liquor of any kind. It so hap- % k4 no ordinary way to escape the invitation, so she & > three men. ° > ac she expected, one of the party led the way to & 3 : Warden, under protest, went along, and under O ¥ test, drank what she could of the schooner of beer. o ¥ he got home she threw aside her breeches, pulled her ¥ s her trunk d dL-h-x'v:.nnL:d to stick to them henceforth, o % Dbe her the privilege of refusing beer when she hated it. o % of this r on was another. She had adopted male attire Q 4 ti erself. + She had suceceded, and she thought & §t dress she could continue to hold what she had o 2 When g John Warden appeared in woman’s attire in Fow. 3 et photograj lery there was the wildest kind of amazement all 2 5 und. In the hubbuby Miss Warren managed to explain why she had & . med the « . and now she is working away there as calmly 2 E v,-.lx as successiully as when she wore breeches and drew the salary of % John Warden, retouch bod E: . Here is the story of Miss Warren’s novel experience as a woman B e sed as a man and working among men. o ’ o B R e Rt R R R R R - T R o R -2 R R =R =R R R e R R R R o HY did I disguise mysnlf]hard it was, too, to learn 'the photo- as a man and work among |graph business. men?” repeated Miss War- | “After thinking the matter over care- fully 1 decided that trousers would be ‘nf more use to me than skirts in my | iew profession, and decided when T left ning, I am a | home to don them. L it doesn’t mat- | “There was another reason, too. You er where, but for some time I have|see, I am a very independent girl anq 1adé to struggle for myself. Pretty |liked to earn my own bread. Well. ren. “Why, the reason is so simple T'm afraid you will not think much of it. “To, in at the be ountry girl, born—w | that Wwomen were not fit to do that sort | | of thing, and wanted me to marry him | | th vas anot k& v T T T, ere was another, a man, who fancied e and settle down and be comfortable. Unfortunately we did not agree on that point. He vowed that he would fol- low me, and so, to throw him off the track, I decided to do what I had so long planned; that is, to disappear as a woman and appear as a plain, every- day working man, trying to earn a living. - “When I reached the city I stopped at a good hotel. and I tell you it eat into my slim little purse, too. of clothes sent to my rooms for my young cousin, Mr. John Warren. “I then went to a lodging-house, cheap, but clean, and secured rooms for the same youneg man. “The next night I packed my satchel and left the hotel, and next morning I hopped out of my room and into the world as Mr. John Warren. “How did it feel? Oh, it was awful, “I fancied every one was staring at me and I felt like bolting into the first friendly doorway that offered its shel- | ter. “My heart beat like a trip-hammer every time I came near a policeman, {and I finally hit upon the plan of cross. ing in the middle of the streets to evada them. At last T mustered up courage to g0 to Mr. Fowzer. *“‘John, brace up and be a man, 1| said to myself. “But in spite of my best efforts it was only after two or three attempts that I pulled myself to- gether and ventured into his office. “Lord heavens, how I quaked and trembled in my shoes when I had to face a real man, and what was worse, talk to him. “However, after a few inward quakes I managed to tell him what I wanted | and he kindly said that he would let me come. “For a long time after that every- thing was quiet. No one seemed to suspect me and I began to feel com- fortable. I liked my suit of clothes best on rainy days, no skirts to pick up and to get drageled in the mud. R4 those days. I felt immensely superior to the rest of my sex. “My cne source of annoyance was the fact that my hair would grow too fast, and finally it got so bad that the hor- rible fear began to dawn on me that T would have to go to a barber and have it cut. “Well, T went. Of course the barber asked me if I wanted a shave. It's a regulation question with them. “I said no rather toc emphatically, I | thought, for the barber stared hard at me for a second and then set to work | on my hair. | *“‘Why, what soft hair you have,” he | said, ‘it's just like a woman's.’ “I'nearly fainted, but managed to mutter that I had often been told so. | “When I got out of his shop, like the man on the Bowery, I resolved ‘To | never go there anymore.’ “Mr. Fowzer has no doubt told you |about the theater invitations that | caused me so much mental worry and anguish. | “It was this way. I make friends | easily, and soon after I came here the | folks Tound here asked me to go out | with them. I escaped whenever I could, but one time they caught me. Mr. Fowzer had asked me to come to the house and make one of a card party. I | thought that it would be all right, so I consented. “We had no sooner started when a | nephew of Mr. Fowzer's came in with |a box for the theater. Mrs. Fowzer | could not go, and I said that I would | rather stay home with her. Seeing, | however, that I could nct do that with- | out attracting surprised attention, I re- | luctantly consented to go. “If you can imagine how I felt sitting in the front of a box with three men, vou will know that the feeling was anything but a jolly one. s “Between one of the act§ one of the party suggested something to refresh the inner man, as he expressed it, though I was thinking of the woman all the while. “I did my very best to escape the in- | vitation, but only succeeded in making | my position worse by refusing to go. Finally I saw that the easiest way to get out of it was to go to the bar with them and make a show af drinking. “Oh, if my family could have seen me. We filed into the bar and they called for beer. “I was too wretched to do anything but nod my head when the¥y asked me if I'd have the same! ‘“Have you ‘ ever seen one of the dreadful things they call ‘schooners of steam beer? “It looked as large as a house to me. If the earth could only have opened and swallowed me I would have been happy. But the earth refused to do it. and still I stood despairinzly look- es, I was supremely happy in‘ QAR N ing at the mountain of foam. | “‘Come, John, drink it. we haven't much time; we don’t wish to miss the next act,’ said Mr. Fowzer, and I started in on that dreadful tower of | beer. | “Well, T got it down, and I can tell | you right here that it was the first and last one I shall ever touch or anything | that looks like it. “When I got home that night T re- | solved that my disguise would have to be dropped. I wouldn't take the risk of having to drink that dreadful steam beer again. I felt, too, that I had won { my way as a worker and that I could | make a living as a woman. | “Soin a day or so I walked into the | gallery in my own .clothes. “You should have seen them stare. | “The dittle boy 'snoke first, “Wh; | what is Mr. Warden doing in woman's clothes, mamma?’ he shouted, and then I was deluged by a perfect flood of questions. “1 explained things to them and ever since then I have been here doing the same work that I always did and find | | | PRy ] » DA W\ rthnt I like my own clothes much bet!r‘r“ than the ones I adopted. “I didn’t find much difference in the | treatment I received from either men or women, but I like my own clothes best, and I never will try to be a man | again. | “You see, I thought it would not only be easier to get around, but I thought it would be cheaper; that a man could | get lodging in cheap places where a | woman would not care to go. “I discovered, however, that it did not make so much difference. “Altogether I find that you can get along in the world, be you either man | or woman, and I think it best not to try | and be an imitation of the opposite sex, | { for you are sure to wish that you | hadn’t before you get through. | | “I shall probably leave here before | |long. My course is almost completed | and I shall want to set up for myself. | “No, T shall riot open a gallery here. I will go into some small place. | “Will I go as a man? Never again. Stick to your own sex, that’s what my | experience has taught me.” REAPPEARING To THE ‘WORLD . ASA MAN H READY FOR WORK. 0 ST, v s A ., —— © V] “Miss Warren carried out her part as a young chap earning a living ex- tremely well,” said Mr. Fowzer. “None of us in the gallery here had the slight- est suspicion that John Warden was anything but a real, up-to-date man, entitled to wear men’'s clothes and work among men as a man. That's the reason we invited him, or rather her, to the theater party. Warden was somewhat shy, but we attributed that to youth and natural diffidence. “When we look back at what hap- pened at the theater party it all seems funny enough now. Warden seemed ap- palled at the size of the schooner of beer. We noticed it, but we men were all thinking ‘about the play and about getting back to our seats, so outside of ‘joshing’ him, or rather her, a bit we did not make anything out of it. “Togged out in her man’s clothes she seemed just like any other young fele low, only, as I said, retiring and quiet. “If you ask the men in the gallery I guess they’ll tell you she makes more of a hit in woman's clothes than in man’s.” [ef=g=F=R=FegcRegReFeFegeFeReRegagoFulaReguRePoRagaFeRegugugeFaPaPugegoPeolzFeogaRogeRaRoRaPuRuaFotugeTuR-Totd < DEALDQOO T HAT advice would I give to a young man ambitious to | become a successful public speaker or orator? 1 In the first place I would advise him to have some- | thing to say—something worth saying something that people would be glad to hear. This is the important thing. | Back of the art of speaking must be | the power to think. Without thoughts { words are empty purses. Most people imagine that almost any words, uttered |in a loud voice and accompanied by ap- propriate gesture, constitute an ora- | tion. 1 would advise the young man to study his subject, to find what others | had thought, to look at it from all | sides. Then I would tell him to write out his thoughts or to arrange them in his mind, so that he would know exactly what he was going to say. Waste no time on the how, until you are satisfied with the what. After you know what you are to say, then you can think of how it should be said. Then you can think about tone, emphasis and gesture; but if you really understand what you say, em- phasis, tone and gesture will take care | of themselves. All these should come from the inside. They should be in perfect harmony ~with the feelings. Voice and gesture should be governed | by the emotions. They should uncon- sciously be in perfect agreement with the sentiments. The orator should be true to his subject, should avoid any | reference to himself. The great column of his argument should be unbroken. He can adorn it with vines and flowers, but they should not be in such profusion as to hide the column. He should give variety of epi- sode by illustrations, but they should be used only for the purpose of adding strength to the argument. The man who wishes to become an orator should study language. He should know the deeper meaning or words. He should understand the vigor and velocity of verbs and the color of adjectives. He should know how to sketch a scene, to paint a picture, to give life and action. He should be a poet and a dramatist, a painter and an actor. He should cultivate his imagi- .| nation. He should become familiar with the great poetry and fiction, with splen- did and heroic deeds. He should be a student of Shakespeare. He should read and devour the great plays. From Shakespeare he could learn the art of expression, of compression, and all the secrets of the head and heart. , The great orator is full of variety— of surprises. Like a juggler he keeps the colored balls in the_ air. He ex- presses himself in pictures. His speech is a panorama. By continued change he holds the attention. The interest does not flag. He does not allow him- HOW TO SUCCEED AS AN ORATOR. By- Robert G. Ingersoll. {=RcXeFegegegeyagegoRogegeRageg=gegclegeogoRegoFegaRagFogegRaFuRaReFagatoFoReoR FoFuRFoF-Tog TR T3 301 | self to be anticipated. He is always in | advance. He does not repeat himself. A picture is shown but once. So, an orator should avoid the commonplace. There should be no stuffing, no filling. He should put no cotton with his silk, no common metals with his gold. He should remember that ‘“gilded dust is not as good as dusted gold.” The great orator is honest, sincere. He does not | pretend. His brain and heart go to- gether. Every drop of his blood is con- vinced. Nothing is forced. He knows exactly what he wishes to do—knows when he has finished it, and stops. Only a great orator knows when and | how to close. Most speakers go on after they are through. They are sat- isfied only with a “lame and impotent | conclusion.” Most speakers lack va- | riety. They travel a straight and dusty | road. The great orator is full of epi- | sode. He convinces and charms by in- | direction. He leaves the road, visits | the fields, wanders in the woods, listens | to the murmurs of springs, the songs | of birds. He gathers flowers, scales the crags and comes back to the highway | refreshed, invigorated. He does not move in a straight line. He wanders | and winds like a stream. Of course no one can tell a man what to do to become .n orator. The great orator s that wonderful thing called presence. He has the strange some- thing known as magnetism. He must have a flexible, musical voice, capable of expressing the pathetic, the humor- ous, the heroic. His body must move in unison with his thought. He must be a reasoner, a logician. He must have | a keen sense of humor—of the laugh- able. He must have wit, sharp and | quick. He must have sympathy. His smiles should be the neighbors of his | tears. He must have imagination. He | should give eagles to the air. and | painted moths should flutter in the sun- | light. | ‘While I cannot tell a man what to do | to become an orator, I can tell him a fe-v things not to do. There should be no introduction to an | oration. The orator should commence with his subject. There should be no | prelude, no flourish, no apology, no ex- | planation. He should say nothing | about himself. Like a sculptor he | stands by his block of stone. Every{‘ stroke is for a purpose. As he works the form begins to ap- pear. When the statue is finished, the | workman stops. Nothing is more diffi- cult than a perfect close. Few poems, few pieces of music, few novels end | well. A good story, a great speech, a perfect poem should end just at the proper point. The bud, the blossom, the fruit. No delay. A great speech is a crystallization in its logic, an efflor- escence in its poetry. To tell the truth, I have not heard many speeches. Most of the great speakers in our country were be- fore my time. T heard Beecher. and he was an orator. He had imagination, | humor and intensity. His brain was | fertile as the valleys of the woplos. He was too broad, too philosophic, too poetic for the pulpit. | great qualities; ‘. 308 108 108 1% 1% 108 0 % o Now and then he broke the fetters of his creed, escaped from his orthodox prison and became sublime. Theodore Parker was an orator. He preached great sermons. His sermons on “Old Age” and “Webster,” and his address on ‘Liberty” were filled with great thoughts, marvelously express- ed. When he dealt with human events, with realities, with things he knew, he was superb. When he spoke of free- dom, of duty, of living to the ideal, of mental integrity, he seemed inspired. Webster I never heard. He had force, dignity, clear- ness, grandeur; but, after all, he wor- shiped the past. He kept his back to the sunrise. There was no dawn in his brain. He was not creative. He had no spirit of prophecy. He lighted no torch. He was not true to his ideal. He talked sometimes as though his head was among the stars, but he stood in the gutter. Clay I never heard. but he must have had a commanding presence, a chival- ric bearing, a heroic voice. He cared little for the past. He was a natural leader, a wonderful talker—forcible, persuasive, convincing. He was not a | poet, not a master of metaphor, but he was practical. Fe kept in view the end to be accomplished. He was the opposite of Webster. Clay was the morning, Webster the evening. ; 3 Clay had large views, a wide horizon. He | was ample, vigorous and a little tyran- nical. Benton was thoroughly common- place. He never uttered an inspired word. He was an intense egotist. No subject was great eriough to make him forget himself. Calhoun was a politi- cal Calvinist—narrow, logical, dog- matic. He was not an orator. He de- livered essays, not orations. S. S. Prentiss was an orator, but, with the recklessness of a gamester, he threw his life away. He said profound and beautiful things, but he lacked ap- plication. He was gneven, dispropor- ticned—saying ordinary things on great occasions, and now and then, without the slightest provocation, uttering the sublimest and most beautiful thoughts. Lincoln had reason, wonderful humor and wit, but his presence was not good. His voice was poor, his gestures awk- ward—but his thoughts were profound. His speech at, Gettysburg is one of the masterpieces of the world. The word “here” is used four or five times too often. Leave the heres out and the | speech is perfect. Of course I have heard a great many talkers, but orators are few and far between. They are produced by vie- torious nations—born in the midst of great events, of marvelous achieve- ments. They utter the thoughts, the aspirations of their age. They clothe the children of “the people in the gorgeous robes of genius. They inter- pret the dreams. With the poets, they prophesy. They fill the future with heroic forms, with lofty deeds. They keep their faces toward the dawn— toward the ever-coming day. Copyrighted, 1898, by S. S. McClure Ca