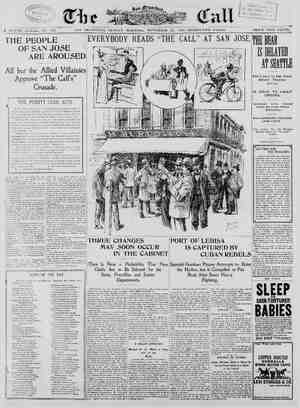

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, November 21, 1897, Page 23

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 1897. LAST POEM, Sunak V- trenrd 5t ik o hesn L2 fo P ol ey T fo o inosmay G fie Bury Vien T pok 0ub b sisy But juck o Lde 09 Moping Toems ollup, T ot frcriod ¥ from., U Hot shick oo from rid Ke breadef dog ng awaited life of Lord 1 appeared. Its literary s the r of v s re- e book is written e poet’s son Hallam, the \ 1wbent of the title, and its \ Toe authenti c is unqgues- onable, which is n than can be said of the bulk of the matter ve of the poet's doings published man averse 10 & self-advertisement or told ot him that one tality and made * never afterward 1 Then it must be r did for us of the nin 1 spears and Chaucer di : their own day. We make this assertion ¢ fiedly and in face of the ren atirit Taine, that the poet a dre: an Epicurean, averting his eyes was unpleasant, from everything that meet bis aproval. Tt may be said ths man whose daily life is placed bzfore open book by his son was far from be be was called by the historian: I we prefer to accept the estiimate of I to the author says that He was a ht savor of T in a letter stands “far awav by the s above all other English poets, with this relative superiority even to Suakespeare, that he sy nd speaks to the perplexities and age.” v striking notes that impress 1 of the volumes before us, not iso touch- the thoughts misgivings of his ¢ There are m upon a per only of the book as a biography. but a ing the character of the man himself. They are wonderfully fascinating, rich 1n anecdote and nent, and hold the attention of the reader the power of anovel. The book is put na peculiar way, sometimes obscure, when one remembers, s contained therein have mentions amone ofher things that he has had to read over 40,000 documents) one is strained to marvel most at the consummate tact with which the poet's son has done hiswc there is noticeable a remarkable scanti detail in the matter of Tennyson’s ecrlier life, regarding which we would gladly know more. Of course when: he became famous, mat- ter regarding him became more and more abun- dant. Hisson has quoted from many writings, not originally intended for the public eye, and many of these were afterward burned by his father’s instructions. Of Tennyson the man we get a remarkably clear view throngh his son’s eyes, an idea that confirms what Mr. Palgrave in his remin- iscences that forty-three years of friendship made him recognize *lovableness” as the dominant note of his friend’s character. That the poet had his weaknesses is admitted, yet tilial reverence has refrained from a direct in- sisience upon them. He thougzht a good deal about himself—most veople do—but any little vanity is perfectly innocent and consistent with simplicity and modesty. Tennyson was sensi- tive. “A fiea will annoy me,” he said to Tyn- dall. “A flea bite will spread a square 1nch ovar the surface of my skin. Iam thin-skinned and 1 take no pains to hide it.” Though the fact might have been apparent to the casual ob- serveritis scarcely noticeabie in the memoir and this tays much for the reverential spiritin whieh the work has been compiled. A certain disjointedness is apparent, as we have said, right through the volumes. The nar- ration is not strictly consecutive, though this is of course attributable to the form of the book The son’s recollection of the father with his cita- tion of the latter’s remarks upon this occasion or that are combined with letters signed by Ten- nyson’s correspondents, and the poet’s own !ez- ters are drawn upon. His contemporaries, among whom may be mentioned Tnackeray, Dickens, Forster, Landor, Leigh Hunt and homas Campbell, contribute something to the interest of the biography. These men he used to meet at the ola Sterling Club, and though it may be vresumed that be talked *'shop” largely, he had wider interests. con- *“T have heard,”” says Lis son, *‘that he always showed an eager interest in tue events and in the great scientific discoveries and economic in- ventions and improvements of the time. His talk largely touched uvon politics, philosophy and theology and the new speculations rife on every side. Upon the projects of reform or the great movements of philanthropy he reflected much.” That poets are born and not made is a saying 80 oft repeated as to have degenerated into a trite commonplace;copybookism, yet to no writer could the remark apply with greater force than to the subject of this biography. We learn that when he was about 8 years of age he covered two sides of a slate “‘with Thompsoanian blank verse in praise of flowers for my brother Charles, who was a year older than I was, Thompson being the only poet I knew.” At 12 years of age he wrote an epic of 4000 lines aiter the manner of Sir Walter Scott. At his grandfather’s desire he also composed a poem on his grandmother’s death, for which the old gentleman gave him half & guinea, with these words, *‘Here;is half a guinea for you,:the first you have ever earned by poetry, and, take my word for it, it is the last!” It appears that Tennyson first becams known in America in the latter part of 1837 or the be- ginning of 1838, Dr. Roife of Camobridge wrote to Hallam Tennyson that “R. W. Emerson somehow made acquaintance with the 1830 and 1832 volumes about that time and deiighted in lending them to his friends.” Tennyson’s poems were quite as popular in this country as in Eng- land. Indeed, 1t is said more copies of his books were sold here, but untii the very last years of his life he received little or no copyright from their publication. ‘I'he chief literary adviser that Tennyson had was his mother. Of her Hallam Tennyson writes: “‘It was she who became my tather’s ad- viger in literary matters. Iam proud of her in- tellect. With her he always discussed what he was working at. It was she who transcribed bis poems and who gave the final criticisms be- fore their publication.”” She is described in the poem of *‘Isabel,’”’ and in her time was among the beauties of the county. The little that is mentioned regarding her and her husband leads Gums ifain Fene T tho' from 61t oy B ) Sine 0 ?Lfév#m.ykuu,éo, Ll Vg T ory Ptr ok us to remark that a clearer knowledge of them would be of assistance to the reader, and cer- tainly would possess much interest fcr him in perusing the work under review. A valuable chapter 1s that describing Tenny- son’s habits. He seems to have been a man of a decidedly moody disposition, and spoke of sui- cide as a subject attractive to him. It is told of him that one evening some one was speaking of a story of a man in Pans having deliverately ordered a good dinner, and afterward committed suicide by covering face with a handxerchiet saturated with chloroform. “That is what I should do,”” Tennyson said, *‘if I thought there was no future life.” His domestic habits were regular. He breakfasted at 8, lunched at 2 and dined at7. At dessert, if alone, he would read to himself; or, if friends were in the houce, he would sit with them for an hour or so and enter- tain them with varied talk. He workea chiefiy in the morning, over his pive, or in the evening, over his pint of port, also over his pipe. Rere books, or books with splendid bindings, he never cared for. Yet he treasured his first edition of Spenser’s “Faerie Queen” and his second edition of *Paradise Lost.”’ He would read over and over azain his favorite authors, and his delight was genuine when he came across a new author who seemed to have ‘‘some- thing in him.” In the matter of reading his tastes were caiholic. He read Stevenson and Meredith, Besant, Black, Hardv, Henry James, Conan Doyle, Hall Caine. These, of course, without reference to the more solid reading that he took up for purposes of study. In attempting to zive some 1dea of Tennyson’s letters one is confronted by a veritable embar- rassment of riches. The statement also holds good with reference to the strictly descrintive matter of the work. The question conironting the reviewer is not what to quote, but what not to quote. Here is one addressed to Walt Whit- man that possesses an undeniable interest to American readers. It isdated in the vear 1887: “Dear Old Man: 1, the elder old man, have received your article and the Critic, and send you in return my thanks ana New Year’s greet- ing on the wings of this east wind, which I trast is blowing softlier and warmlier on your good L gray bead than here, whera it is rocking the elms and ilexes of my Isle of Wight garden.” He has a word of praise, too, for Mr. Kipling's inglish Flag,”” and expressed his pleasure in a letter to him. Here is Mr. Kipling’s answer, characteristic and well caiculated to give Ten- nyson satisfaction: “When the private in the ranks 1s praised by the general he cannot presume to thank him, but he fights the better next day.” The simple tastes of the poet were made more and more apoarent in the last days of his life and in the circumstances attending kis death, about which his son talks freely. These are still fresh in the minds of his admirers. His last words breathed a blessing on his wife and son, who thus describes the preliminaries of the funeral: *“We placed ‘Cymbeline’ with himand a laurel wreath from Virgil's tomb, and wreaths of roses—a flower which he loved above all flow- ers—and some of his Alexandrian laurel—the poet’s laurel. On the evening oi the 1lth the coffin was set on our wagonette, made beautiful with stag’s horns, moss and a scarlet lobelia car- dinalis, and draped with the pall woven by men and women of the North and embroidered by the cottagers of Keswick; and then we covered him with the wreaths and crosses of flowers sent from all parts of Great Britain. The coachman, who had been for more than thirty years my fatner’s faithful servant, led the horse.” In bringing to a close an all too incomplete notice of this “Book of the Year,” it may be prophesied that its success will exceed that of any biography published for a long time. Within its pages are contained much of the hitherio unpublished poetry of its noble subject, but the memoir will be valued not for tnis, but for its vivid por- traiture of a man of genius and for the doings it narrates and writings which it quotesof half the notabilities of the Victorian era. It is a book that, were it written of anybody else and sub- mitted to the late Lord Tennyson himself, would exact from him his praise, notwithstanding his distaste for biography as he saw it in his time, and as it was practiced by Forster and Froude. In the current issue of the London Quarterly Review an anecdote is quoted to show what his views on the subject were. Said Lord Tenny- DY TENNYSON. son: *“The biographer who loves his man either paints his man as he saw him and knew him, always loving him, or leaves the man to tell his own tale through his letters and conversations. In the one case the biographer may be called a bore and in the other his work may be dubbed incomplete. But, for God’s sake, let those who love us edit us after death.”” Now, let a word be said for the debt that is due from the literary worid to Hallam, Lord Tennyson, for his industry, for the love and painstaking care which is apparent in this me- moir, which has taken him four years to com- plete, for his uniform taste and judgment, for his correct sense of the fitness of things and for his regard not alone for effeciiveness, but for truth and justice. The book is absolutely au- thoritative. The proofs were corrected by Lady Tennyson beiore her death in August, 1896, and if errors are found in it let them be placed as those, not of taste and judgment, but of love. Emaxver Evrzas. Crossing the Bar. Sunset and evening star, And one clear cali for me! And may there be no moaning of the bar, When I put out to sea. But such a tide as moving seems asleep, Too full for sound and foam, When that which drew from out the boundless deep Turns again home. Twilight and evening bell, And after that the dark! And may there be no sadness of farewell, When [ embark ; For tho’ from out our bourne of Time and Place The flood may bear me far, 1 hope to see my Pilot face to face When I have cross’d the bar. [Tennyson’s last poem. It was set to music by Sir John Bridge and chanted at the poet’s funeral.] F&! THE LOVE OF TONITA-E Fleming Fmtrce. Chicago: Herber i« se by W. Doxey, Palace Hotel This is & collection of nine short stories of the Mexicsn order, well told and full of inci- dentand good description. Love and blood- shed go b in band, and if one story hasa tragic ending that of the following is sure to be humorous. Tne first tale, ana that which pames the book, shows how & young Mexi- can maiden loves & Bpanish youth whose affection for her has been charmed away by his fair cousin. The Mexican girl has & brother who 15 opposed to the marriage, and who finally manages to prevent it, although he breaks his sister's heart by so doing. *Cold Facts” shows the author in a lighter mood, and he therein telis a cowboy varn which is equal to eny spun by Munchausen. Typo- graphically the book is a beauty. EARLY AMERICAN LATIN. Tae following is from a letter of Edward Everett, printed in the Harvard Graduaies’ | Magazine, under date of Gottingen, September | 17, 1817: I blushed buraing red to the ears | the otner day as u friend here lafd his hand upon a newspaper containing the address (in Latin) of the students at Baltimore to Mr. Monroe, with the transiation of it. It was less matter that the transiation was not Eng- | lish; my German friend could not detect that. | But that the original was not Lasin I could | not, alas! conceal. It was, unfortunatsly, just like enough to very bad Latin to make it impossible to pass it off for Kickapoo or Pot- tawatomie, which I was at first inclined to attempt, My German friend persisted in it that it was meaut for Latin, and I wished in my heart that the Baltimore lads wou1d stick to the example of their fathersand mob the Federalists, so they would give over this in- human violence on the poor old Romans.” A SMOGTH SCOUNDREL. AN AFRICAN MILLION A IRE—By Grant Allen, New York: Edward Arnold. The “African Millionaire” is presumably a “soft thing’” to the smart London shark who camps on his trail and bleeds him time and again out of thousands of pounds. He has made his fortune out of speculating in dia- monds, and makes a trip through the Conti- nent for a rest, his private secretary for com- pany. Tue man who succeeds in relieving him 80 often of his cash is certalnly one of the smoothest rascals ever portrayed on paper. He issuch a master at his art that one follows his career with breathless interest. When at last he is rounded up ia England and sen- tenced to fourteen years’ imprisonment at hara labor, one almost feels like sympathizing with him instead of with his vietims, who, 1n anotker way, were just as bad as he. Grant Allen’s style is at all times simple and pol- ished. He never draws preposterous charac- ters, and the men and women in this book are no exceptions to this general rule. A GROTESQUE ROMANCE. THE INVISIBLE MAN—By H G. Wells. New York: Edward Arnold. This 18 the history of an invisible being and his doings in an English village. Afier caus- ing the villagers no end of trouble they sue- ceed in killing him, end he materializes with death. The idea is an original one, but the WHEN GREEKS WERE GODS. CYPARISSUS—By Ernest Eckstein. New York: George Gottsberger Peck. Mr. Eckstein is one of the best writers of the classical historical romance of to-day. He is well versed in the customs of Greece and Rome, his stories all deal with that period. “Cyparissus” is the name of a Greek hero in the present tele, who is finally made king of Andros in place of a despot and who proves himself kingly in more ways than one. author is incapable of treating it properly. | The story is graphically told.