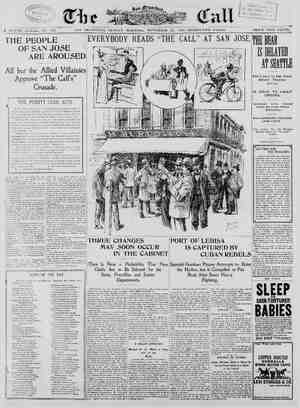

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, November 21, 1897, Page 19

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 21 1897 19 e Awm r Schlachtstadt ad just broad Koe alley i that held cc te always seemed | uninhabited fidence yerspe to n ctive the U lans, sty, , caval- with or ere n- g no- | butcher and possible Alderman; one and | rvice— 2 | cnief, and 1aid them, with fingers more or less worn and stubby from hard service, before the | Consul for his signature. Once, in the case of avery young madehen, that signature was | blotted by the sweep of a flaxen brald upon it | as the child turned to go, but generally there was & grave, serious business instinct and sense of responsibility in these girls of ordi- pessant origin which, equally with their crs of France, were unknown to the Eng- lish or American woman of any class. That r:orning, however, there was a slight | stir among those who, with their knitting, were waiting their turn in the outer office as | the Vice-Consul ushered the police inspector into the Consul's private office. He was in | uniform, of course, and it took him a moment | to recover from his habitual stiff, military | sulute—a little stiffer than that of the actual soldier. It was a matter of importance! | had that morning been arrested in the town and identified as a military deserter. He claimed to bean American citizen; he was now in the outer office waiting the Consul’s | interrogation. The Consul knew, however, that the ominous accusation had only a mild significanca here. Tae term “military deserter” included any one who had in youth emigrated to & foreign ry without first fulfilling his military o his fatherland. His first experiences y of these cases had been tedious and difficalt— volving a reference to his Minister at Ber- lin, & correspondence with the American State Department, a condition of unpleasant ten- sion, and finally the prolonged detention ot some innocent German—naturalized—Ameri- can citizen, who had forgotten to bring his ith him in revisiting his own native A stranger nced, however, that the Consul en- j iriendship and confidence of General Adlerkreutz, who commanded the Twentieth Division, and it further chanced that the same Adlerkreutz was as gallant a soldier as ever cried ‘“Vorwarts!” at the head of his men, as profound a military strategist and organ- | izer as ever carried his own and hisenemy’s | plans in his iron head and spiked helmet, and ‘)N with as simple and unaffected a soul breathing under his gray mustache as ever | issued from the lips of a child. So this grim but gentle veteran had arranged with the | Consul that in cases where the presumption of | nationality was strong, al:hough the evidence Was not present, he would take the Cousul's perole for the appearance of the “deserter” or his papers, without the aid of prolonged | diplomacy. Iu this way the Consul had saved | to Milwaukee a wealthy but imprudent brewer, and to New York an excellent sausage but had re- turned to martial duty one or two tramps or urneymen who had never seen America, lace. In | except from the decks of the ships in which ca r of one pat- | they were “stowaway” &nd on which they on which | were returned. And thus the temper and Col igh t ‘H s and e ge cap—was sub oving pov poly oah the when er er unreality; xed np with 1 to mind o licaicting k when on see & Tegiment er, laden d want 1 search bs, to s in the ons charge Platz o he Exerzi i swords in mmand of an off nd it People g r Max * in e ready rush o o do therland between the es, only looked upon these the light of sticks and umbrellas, ed their souls in peace. And whean, s singular incongruity, many of were spectacled, studious their lethal weapons, wore a essional air, and Were—to a man— tin 1 and singulariy u 3 attitude in this eternal Kriegspiel seemed to the Cousul more puzzling than ever. As he e red his consulate he was con- frouted with another aspect of Schlachtstadt, as wonderful, yet already familer to or, in spit these “alarums with- t,” which, how: r, never seermned to pene- trate beyond the town itself, Schlachtstad: and iis suburbs were known all over the rid for the manufactures of certain beauti- textile fabrics, and many of the rank and of is A haboan: on- reral of soldiers e | striplin uld be more de- | | peace of two great nations were preserved. “He say: saia the pector, severely, “that he isan American citizen, but he lost his naturalization pay Yet he has made the demaging admission to others that he ived several vesrs in Rome! And,” ued the inspector, looking over his der at the closed door as he p'aced his finger beside his nose, “he says he has relations liv ng at Palmyra, whom he frequently visit Ach! Observe this unheard-of-and-not-to-be trusted statement!” The C ul, however, smiled with a slight | flash of intelligénce. “Let me see him,” he i y passed into the outer office—another oliceman and a corporal of infantry saluted and rose. In the center of an admiring and sympathetic crowd of Dieustmadchen sat the | cutprit, the least concerned of the parts; a —a boy—scarcely out of his teens! t was fmpossible to conceive a more bucolic and almost angelic-looking t With a skin that had the peculiar and rosiness of fresh pork, he Lad blue wide open and staring, and docculent yellow curls of the sun He might have been an overgrown and v dressed Cupid, who had innocently wandered from Papnian shores. | the Consul entered, and wiped from his full red 1 of asausage he was eating. The Consul re- | cognized the fiavor at once—he had smelled it | before in Leibschen’s little hand basket. ‘ “You say you lived st Rome?” began the | Inaeed, noce derelic Consul pleasantly. *“Did you take out your st declaration of your intention of becom- ing an American citizen there?’ The inspector cast an avproving glance at the Consul, fixed a stern eye on the cherubic prisoner, and leaned buck in his chair to heag the reply to this terrible question. ting his brows in infantile thought. “It was elther there or at Madrid or Syracuse.” 1 The inspector was about to rise; this was | really trifling with the dignity ot the muniei- | pality. But the Consul laid his hand on the | official’s sleeve, and, opening an American | atlas to a map of the State of New York, saia | to the prisoner s he placed the inspector’s | finger on the sheet, “I sce you know the | names of the towns on the Erie and New York | Central Railroad, but—" ' “I can tell you the number of people in each | | i rupted the young {ellow vanity. “Madrid has 6000, and there are over 60,000 in—"" | “That will do,” said the Consul, as a mur- | mur of “Wundershon!” went round the group | of listening servant-girls, while glances of ad. miration were shot at the beaming accused. | “But you ought to remember the name of the | town where your naturalization papers were | afterward sent.” “But I was & citizen from the moment I made my declaration,” said the stranger smiling | and looking triumphantly at his admirers, “and I could vote!” The inspector, since he had come to grief over American geographical nomeneclature, was grimly taciturn. The €onsul. however, was by no means certain of his victory. His ledge; a clever youth might have crammed for this textbook information—but then he did notlook at all clever; indeed, he had rather the stupidity of the mythological subject he represented. “Leave him with me.” saii the Consul. The inspector handed him a ecis of the case. The cherub’s name was Schwartz, an orphan, missing from Schlachstadt since theage of 12. Relations ing or in emigration. Identity estab- lished by prisoner’s admission and record. “Now, Karl,”” sald the Consul cheerfully, as the door of his private office closed upon them, “what is your i game? Have you er had any papers? And if you were clever enough to study the map of New York State, ren’t you clever enough to see that it | wouldn’t stand you in place of your papers?”’ “Dot’s joost it,”” said Karl in English; “but vou see dot if 1 haf deciarit mine intention of b L:'ummingn citizen, it's all the same, don't By no means, for you seem to have no evi- dence of the declaration—no papers st all.” |, “Zo!” said Karl. Nevertheless he pushed | the small, rosr, pickled-pig's-feet of fingers | through his fleecy curls and beamed pleas- | antly at the Consul. *Dot’s wot's de matter,” h s1id, as if taking a kindly interest in some private troule of the Consul’s. “Dot's vere you vos, ek | The Consul Jooked steadily at him for a mo- ment. Such stupidity was by no means phe- ¢ of those warriors had built up the fame | nomenal nor 11 ! at all =04 prosperity of the disirict over their eace- | pearance. - Apts onsilent with bis ap, ful looms in wayside cottages. There wers | gravely, I must tell you that umless you at depots and counting-houses, larger than 1 tie cavalry barracks, where no other form but that of the postman was known. t was that the Consul’s chief duty was the flag of his own country by the ation voices s¢ Bu his office by the manufacturers. enough, these business messen- gers chiefly women—not clerks, but ordinary household servants, and on busy days t ulate might have been mistaken for & fema e registry office, so filled and pos- sessed it was by waiting madchen. Here it was tha lien, Liescnen and Clarchen, in the cle ot blue gowns and stoutly but smartly shod, breught their invoicesin a piece of clean paper, or folded in a blue handker. and certification of diversin- | nave other proofs than you have shown it will be my duly to give you up to the authorities. g _““Dot mean Ishall serve my time, eh?” said Karl, with an unchanged smile. | “Exectly 50,” returned the Consul. | “Zo!” said Karl. “Dese town—dese Schlach- | stadi—is flne town, eh? Fine vomens. Goot men. Und beer und saussge. Blenty to eat und trink, eh? Und,” looking around the | room, “you und te boys haf a gay times.” “Yes,” said the Consul shortly, turning away. But he presently faced round again on the unruffied Karl, who was evidently in- dulging in a gormandizing reverie, “What on earth brought you here, any- way?” “Vas is da: con- | houl- | He smiled as | s with the back of his hand the trac-s | I don’t remember,” said the culprit, knit- | town and what ere the manufactures.”” inter- | with youthful | w-citizen was too encyclopadic in | ————— — BRET HARTE- ——————————0 “What brought you here from America—or | wherever you ran away from?” *To see te vol “But you are an orphan, you know, and y ! have no folks living here?” | “‘But all Shermany is mine volks—de wholc country, don’t it? Pet your boots? How’s dot | en?” | The Consul turned biack to his desk and | | wrote a short no: to General Adlerkreniz in his own American-German. He did not think it his duty in the present case to inter'ere with the antnorities or to offer his parole Zor Karl Schwartz. But he would claim that as the offender was evidentiy an innocent emi- grant and still young, any punishment | or military degradation be omitted, and he be allowed to take his place like any other re in cruit in the ranks. 1f he mi:ht have the | temerity to the undoubted, ‘ar-secing military | authority, of suggestion msking here—he would suggest that Karl was for the commis sariatfitted. Of course, he sti!l retained the right, on production of satisfactory proof, his | discharee to cisim. | The Consul read this aloud to Karl. The | cherubic youth smiled and said, * ' Then | extending his hand he added the word, “Z-<hakel” The Coasul shook his hand a little remorse- fully and preceding him to the outer room re- signed him with the note into the inspect hands. A universal sigh went up from the | girls and giances of appeal sought the Co | sul, but he wisely concluded that it would b> well, for a while, that Karl, a helpless orpnan. should be under some sort of discipline. And the securer business of certiiying invoices re- commenced. Late that afternoon he received a folded bit of blue paper from the waistbelt of an or- derly which contained in English character: and s a single word, “Alright,” followed by certain jagged pen marks, which he recog- nized as Adlerkrentz’s signature. But it not until a week later that he learned any- thing definite. He was reiurning one night to his lodgings in the residential part of the | city, and in opening the door with his pass- key per maiden, Trudschen, attended by the usual blue or yellow or red shadow. He was passing by them with the local “’n 'abend!” on h lips when the soldier turned his face and luted. The Consul stopped. It was the cherub Karl in uniform. | Butithad not subdued asingle one of his | characteristics. Ilis bair had been cropped a little more closely under his cap, but there | was its color and wooliness still 1ntact; his | plump figure was girt by b21t and buttons, but | he only looked the more unreal and more !ike | & combination of penwiper aud pincushion, until his pufty breasts and shoulders seemed | to offer a positive invitation to anv one who | had picked up & pin. But wonderfull—ac- cording to his brief story—he had been so pro- | ficient in the goose step that he had been put | an uniform already and allowed certain | small privileges—among them evidentiy the present one. The Consul smiled and passed | en. Butit seemed strange to him that Trud- schen, who was & tall, strapping girl, exceed- | ingly popular with the military and who had never looked lower than a corporal at least, | should accept the attentions of an eivjahriger | like that. Later he interrogated her. “Ach! it was only Unser Karll Consul knew he was Amerikanisch” “Indeed!” “Yes! It was such a tearful story.” “Tellme what it is,” said the Consul, with & faint hope that Karl had volunteered some communication of his past. “Ach, Gott! There In America he was & man—and could ‘vote,” mske laws and, God willing, become a town councilor or ober intendant, and here he was nothing but a soldier for years. And this America was a fine country. Wundershon! There were such big cities, and one, ‘Booflo,’ couid hoid all Bchlacntstadt, and had of people 500,000 The Consul sighed. Zarl had evidently not yet got off the line of the New York Central and Erie roads. ‘“But does he remember yet | what he did with his papers?” said the Consul persuasive'y. “Ach! What does he want with papers | when he could make the laws. They were dumb, stupid things, these papers to him.” “But his appetite remains good, I hope?” suggested the Consul. This closed the conversation, although Karl came on many other nights, snd his toy figure quite suppianted the tall corporal of hussars in the remote shadows of the hall. One night, however, the Consul returned home from a visit to & nelghboring town a day earlier than he was expected. As he neared his house he was a little surprised to find the windows of his sitting-room lit up, and that there were no signs of Trudschen in the lower hall of passages. He made nhis way upstairs inthe dark ard pushed open the door of his spartment. To his astonishment Karl was sitting comfortably in his own cnair, his cap off, before & student lamp on the table, deeply engaged in apparent study. So profound was his abstraction that it was a moment before | | Ana the 1 at his usually beaming and responsive face, which, howe ver, now struck him as wearing a singular air of thought and concentration. When their eyes at last met he rose instantly and saluted, and his beaming smile returned. But either from his natural phlegm or extra- ved in tbe rear of the hall his hand- | he looked up and the Consul had a good look | ordinary self-control, he betrayed neither em- varrassment nor alarm. | The explanation he gave was simpie. Trudschen had gome out with the | Corp Fritz for a short walk, and had asked him to “keep house” during their absence, He | had no hooks, no papers, nothing to read in the barracks, and no chance to improve his ind. He thought the Herr Consu! would not object to his looking at his books. The Consul was touched—it was really a trivial indisc tion—and as much s Trudschen’s fault as Karl's! to improve—his recent attitude ¢ gested thought and reflection—the Consul were a brute to reprove him. He smiled pleas- «utly as Karl returned a stubby bit of pencil and some greasy memoranda to his breast [ tand gianced at the table surprise it was & large map that Karl nad been studying, and to his still greater surprise, a | map of the Consul’s own distric:. “You seem to be fond of map atudying,” said the consul pleasantly. “You are not thinking of emigrating again ?” “Ach, no!” said Karl simply, “it is my cousine vot haf lif near here. I find her.” But be left on Trudschen’s return, and the Consul was surprised to sec that, while Karl's attitude toward her had not changed, the girl exhibited less effusiveness than before. Be- ieving it to be partly the effect of the return of the sergeant, the Consul fajthlessness; but Trudschen looked grave. “Ah! He has new friends—this Karl of ours. He cares no more for poor girls like us. When fine ladies like the otd Frau von Wimpfel makes much of him—what will you?” It ap- peared, indeed, from Trudschen’s account that the widow of & wealthy shopkeeper had made a kind of protege of the young soidier and given him presents. Furthermore, that the wife of his eolonel had employed him to act as page or attendant atan efternoon gesellschait, and that since then the wives of other officers had sought him. Did not the Herr Consul think it was dreadful that this American, who could vote and make laws, should be sub to such things? The Consul did not know what to think. It seemed to him. however, that Karl was *‘get- tingon,” and that he was in no need of hs assistance. It was in the expectation of hear- ing more about him, however, that he cheer- fullv accepted an invitation from Adlerkreutz todine at the caserne one evening with the staff. Here he found, somewhat to his embar- rassment, that the dinner was partly in his own honor, and at the close of five courses and the emptying of many bottles his health was proposed by the gallant veteran Adler- kreutz in & neat address of many syllables containing a1l the parts of speech and a single verb. Itwas to the effect thet in hissoul never-to-be-severed union of Germania and Columbla, and In their perfect understanding was the war-defying alliance of two great na- tions, and that in the Consul's nobie restora- tion of “Unser Kar!” 1o the German army there was the astuts diplomacy of a great mind. He was sstisfied that himself and Herr Consul still united in the great future, looking down upon a common brother- hood—the great Germanic-American confed- eration, wouid feel satisfied with themselves and each other and their never- orgotten | earth-iabors. Cries of “Hoch! Hoch!” re- sounded through the apartment with the grind ing roll of heavy-botiomed beer-glasses, and the Cousul, tremulous with emotion and areserve verb in his pocket, rose to reply. Fully embarked upon this perilous voyage, and steering wide and clear of any treacher- ous shore of intelligence or fancied harbor of understanding and rest, he kept boldly out at ses. He said that, while his loving adversary in this battle of compliment had disarmed him and left him no words to reply to his generous panegyic, he could not but join with that gallant soldier in his | heartfelt aspirations for the peaceful a liance of both countries. But, white he fully reciprocated all his host’s broader and higher seutiment, he must poiat out to this galiant sssembly the glorious brotaer- hood, that even a greater tie of sympathy knitted him to the generai—the tie of kin- ship! For, while it was well known to the present company that their gallant com- mander had married an Euglish woman, he, the Consul, although always an American, would now for the first time confess to them that he himself was of Dutch descent on his mother’s side! He would say no more, but confidently leave them in possession of the treméndous significance of tnis until then un- known fact! He sat aown with the forgotten verb still in his pocket, but the applause that followed this perfectly conclusive, satisfying and logical climax convinced him of his sue- cess. His hand was grasped eagerly by suc- cessive warriors; the general turned and em- braced him before the breathless assembly; there were tears in the Consul’s eyes. As the festivilies progressed, however, he found 1o his surprise that Karl had noi only become the fashion as a military page, but that his native stupidity and sublime simplic- ity was the wondering theme and inexhaust- ible delight of the whole barrucks. Stories were told of his genius for blundering which rivaled Handy Andy’s; old stories of fatuous ignorance were rearrangea and fitted to “Qur Karl.” It was “Our Karl” who, on receiving | n tipof 2 marks from the hands of a young lady to whom he had brought the bouquetof a direct and | nd if the poor fellow had any mind | tainly sug- | But to his | taxed her with | friend, the Herr Consul, and himself was the | gallant lieutenant, exhibited some hesitation, | and finaliy said, *Yes, but gnadige iraulein, | that cost us 9 marks!” It was “Our Kar.” ) who, interrupting the regrets of another lady that she was unable to accept his master’s in- vilation, said polit:ly: “Ah, what matter, |gn.mgm. I heve still a letier for Frau- lein Kopp (her rival) and I was told that I must not invite you both.” It was our | Karl who astonished the hostess to whom he wassent at the last moment with apologies | rom an officer, unexpectedly detained at bar- | rack duty, by suggesting that he should bring that unfortunate officer his dinner from the | just served tuble. Nor were these charming | infelicities confined to his social and domestic | service. Although ready, mechanical and in | variably docile in the manual and physical du | ties of a soldier—which endeared him to the | German drillmaster—he was still invincibly orant ns 10 its puzport, or even the mean- g and structure of the militery instru- ments he nandied or vacautly looked |wpon. It w “our Karl” who sug- | zested to his instructors that in field £ it was quicker and easier to load his musket to the muzzle at once and get rid | of its death-dealing contents atasingle dis- | enarge th ioad and fire concecutively. It was “our Karl” who nearly killed the in- structor at sentry drill by adhering to the | | 1 the password. It was the same admonished for his reck- sness. the next iime added to his challenge the precaution, “Unless you instantly say ‘Fatherland,’ I'll fire!?” Yet his perfect good { humer and childlike curiosity were unmis- tukable througnout, and incited his comrades | and his superiors to show him everything in the hope of gotting some characteristic com- ment from him. Everything and everybody were open to Karl and his good-humored sim- plicity. That evening as the general accompanied the Consul down to the gateway and the waiting carrinze a figure in uniform ran | spontaneously before them and shouted ““Heraus!” to the sentries. But the general promptly checked *“ihe turning out” of the guard with & paiernal shake of his finger to | the over-zealous soldier, in whom the Consul recognized Karl. *He is my burshe now,” | said the general, explanatorily; “my wife has teken a fancy to him. Ach! he is very popu- lar with these women.” The Consul was still | more surprised. The Frau Generaliss Adler- | kreutz be knew to be a pronounced Engiish woman—carrying out her English ways, proprieties and prejudices in the very heart of | Schlachstadt uncompromisingly, without fear | and without reproach. | 10w & merely foreign society eraze or alter her | English household so as to admit the jmpos- | sibie Karl struck him odaly. had forgott Karl who, severe! ) news of Kari, wien one afternoon he sud- denly turned up at the consulate. He had again sought the consular quiet to write a few letters home; he had no chance in the confinement of the barracks. | “But by this time you must be in the family of a fleld marshal at least,” suggested the | Consul pleasantiy. t to-day—but next week,” said Karl with sublime simplicity, “then Iam going to with the Governor commandant of fhfestung.” The Consul smiled, motioned him to a seat at a table in the outer office and left him, un- disturbed, to his correspondence. Returning later he found Karl, his letters finished, gazing with cnildish curiosity and admiration at some thick official envelopes, bearing the stamp of the consulate, which were lving on the table. He was evidently struck with the contrast between them and the thin, flimsy affairs he was nolding in his hand. He avpeared still more impressed when the Consui told him what they wera. “Are you writing to your iriends?” con. tinued the Consul, touched by his simplicity. “Ach ja!l" said Karl eagerly. “Would you tike to put your letter in one of these envelopes?” continued the official. suficient answer. After all, it was a small favor granted to this odd waif who seemed to still cling to the consular protection. He handed him the envelops and left him ad- dressing it in boyish pride. It was Karl’s last visit to the consulate. He appeared to have spoken truly, and the Con- sul presently learned that he had indeed been transferred through some high official manipulation to the personal service of the Governor of Rheinfestung. There was weep- ing among the Dienstmadchen of Schiacht- stadt, and a distinct loss of originality and tightness in the gatherings of the gens tler damen. His memory still survived in the barracks through the later edt- tiors of his former delightful stupidities— many of them, it is to be feared, were inven- tions—and stories that were supposed to have come from Rheinfestung were described in the slang of the offiziere as being ‘“colossal.” But the Consul remembered Rheinfestung and could not imagine it as a home for Karl, or in any way fostering his peculiar qualities. For |it was eminently a fortress of fortresses, a magazine of magazines, & depot of depots. It was the key of the Rhine, the citadel of West- phalia, the “Clapham Junction” of German raflways, but delended, fortified, encom- passed and controlled by the newest as well as the cldest devices of military strategy and science. Even in the pipingest time of peace whole railway trains went into it like & rat in a trap, and might have never come out of ii; it stretched out an inviting hand and arm across the river that might in the twink.ing of an eye he changed 0 a closed fistof menace. You “defiled” into it, commanded at every step by The beaming face and eyesof Kurl werea ! letter of his instructions when that instructor | That she should fol- | A month or two eiapsed without further | | gered on his way to his new post. | i | lovingly. enfilading walls; you *debouched” out of it, as you thought. and found yourself only be- fore che walls; you “re-entered” it at every possible angle; you did everything apparently but pass through it. You thought yourse!f well out of it, and were stopped by & bastion. Iis circumvallations haunted you until you came to the next station. It had pressed even the current of the river into its defensive service. There were secrets of its foundations and mines that only the highest military des- pots knew and kept to themselves. In a word it was impregnable. That such a place could not be trified with nor misunderstood in its right-and-acute- angled severities seemed plain to every one. But set on by his companions, who were showing him its defensive ioundations, or in his own idle curiosity, Karl managea to fal! into the Rhine, and was fished out with diffi- culiy. The immersion may have chilled his military ardor or soured his good humor, for later the Consul neard that he had visited the American consular agent atan adjacent town with the old story of his American citizenship. “He seemed,’” said the Consul’s colleague, ‘‘to be well posted about American railways and American towns, but he hnd no papers. He lounged around the office for & while and . g ““Wrote letters home ?” suggested the Consul with & flash of reminiscence. “Yes; the poor chap had no privacy at the deviled. This was the last the Consul heard of Karl Schwartz directly. again fell into the Rhine, this time so fatally and effectually that, in spite of the efforts of his companions, he was swept away by the rapiG current, and thus ended his service to his country. His body was never recovered. A few months before the Consul was trans- ferred from Schlachstadt to another post his memory of the departed Karl was revived by a visit from Adlerkreutz. The general looked grave. {ou remember Unser Karl?” he said. “Yes, “Do you think he was an impostor?” “As regards his American citizenship, ves! But I could not say more.” “So!” said the general. “A very singuler thing has happened,” he added, twirling his mustache. “The inspector of police has noti- fied us of the arrival of a Karl Schwartz in this town. It appears that he is the real Karl Schwartz, identified by his sister as the only one. The other, who was drowned, wes an impostor. Hein?” “Then you have secured another recruit?”’ said tne Consul, smiling. “No. For this one has already served his time in Elsass, where he went when he left here as a boy. But, donnerwetter, why should thatdumb fool teke his name?" “By chance, [ fancy. Then he stupidly stuck to it, and had to take the responsibilities with it. Don’t you see?’said theConsul, pleased with his own cleverness. “Zo-0!” said the general slowly, in his aeep- est voice. But the German exclamation has a varfety of significance, according to the in- flection, and Adlerkrentz’ ejaculation seemed to contain them all. S It was in Paris, where the Cor FON ul had lin- He was sit- ting in a well-known cafe, among whoss hab- itues were seversl military officers of high rank. A group of them were gathered around & table near him. He was idly waiching them with an odd recoliection of Schlachstadt in his mind, and as idiy glancing from them to the more attre boulevard without. The Consul was getting a little tired of soldiers. Suddenly there wasa slightstir iz the ges- ticulating group and a cry of greeting. The Consul looked up mechanically, aad then his eyes remained fixed and staring at the nev comer, for it was the dead Karl; Karl, surely Karl, his plump figure belted in a French of - barracks, and Ireckon was overlooked or be- | For a week or two later he | cer’s tunic, his flaxen hair clipped a little closer, but its fleece showing under his kepi; Karl, his cheeks more cherubic than ever, un- changed bul for & tiny yellow toy mustache curling up over the corners of his full lips; Karl, beaming at his companions in his old way, but rattling off French vivacities witn- out the faintest trace of accent. Could he be mistaken? Was it some phenomenal resem- | blance, or had the soul of the German private been transmigrated to the French officer. The Consul hurriedly called the garcon. “Who is that officer who has just arrivea ?"" «“It is Captain Christian of the intelligence bureau,” said the waiter with proud alacrity. “A famous officer, brave as a rabbit—un fier lapin—and one of our best clients. So droll. too, such a ferceur and mimic. M'sidw, would be ravished to hear nis imitations.” “But ne looks like a German; and hu name ?” “'An, he is from Alsace, But nota German,” said the waiter, absolutely whitening with in- diguation. “He was at Beliort. So was L Mon Dieu ! No, a thousand times po I'” ““But has he been living herelong ?* said the Consul. “In Paris,a few months. But his depart- ment, m’sieur understands, takes him every- where. Everywhere where he can gain in- formation.”” The Consul’s eyes were still on Captain Christian. Presently the officer, perhaps in- stinctively conscious of the serutiny, looked towerd him. Their eyes met. To the Consul's surprise the ci-devant Karl beamed upon him and advanced with outstretched hand. But the Consul stiffened slightly and re- mained so, with his glass in his hand. At which Captain Christian brought his own easily 10 a military salate and said, politely: “Monsieur le Consul has been promoted from his post. Permit me to congratulate him.” ou have heard, then?” said the Consul, dryly. “Otherwise T should not presume. For our department makes 1t & business—in Monsieur le Consul’s case it becomes a pleasure—to know everything.” “Did your department know that the real | Karl Schwartz has returned ?” said the Consul, dryly Captaln Christian shrugged his shoulders. “Then it appears that the sham Kari died none too soon,” he said lightly. *‘And yet—" he bent his eyes with mischievous reproach upon the Consul. “Yet what?” demanded tne Consul, sternly. “sonsieur le Consul might have saved the unfortunate man by accepting him as an American citizen and not helped to force him into the German service.” Tne Consul saw in a flash the full military significance of this logic and could not repress asmile. At which Captain Christian dropped easily into & chair beside him and as easily into broken German English: | “Und,” he went on, “dees town — dees Schlachstadt is fine town, eh? Fine vomens? Goot men? Und beer and sausage? Blenty to eat and trink, eh? Und you und te poys haf a gay times?” The Consul tried to recover his dignity. The waiter behind him, recognizing only the delightful mimicryof this adorable officer, was in fits of lnughter. Nevertheless, the Con- sul maneged to say, dryly: ““And the barracks, the magazines, the com- missariat, the details, the reserves of Schlachte stadt were very interesting?” “Assuredly.” “And Rheinfestung—its plans—its details, | even its dangerous foundations by the river— they were 10 a soldier singularly instructive?” “You have reason to sayso,” said Captain { Coristian, curling his little mustache. ““And the fortress—you think «Impregnable! —17 | The Consui remembered General Adler- | kreutz’s “Zo—o,” and wondered. THE END. i Years have passed since the voice through these rooms. occupant of the room, sitting so dreamily part of a lovely old-fashioned picture. But this is a recent picture. to a lover or husband? does not hear it. arms to greet him. strong arms about his mother’s form. The white-haired Woman;looks dream have heard his words. | ““] am so glad you have come, Albert, You have been gone so long, darling, and “‘Poor old mother ! form tightly. “I am so tired, dear,” she said. said you were coming for me; so I wasn’t tired, Albert. before you went away.” to take me with you.” white lips, murmuring: ““Truly, he has c Extreme old age is written everywhere. “‘Sit down here where I can look at you. you remember how we sat here the day you brought me home as your bride? It seems so long ago, but you look no older. A THANKSGIVING FANCY. T IS Thanksgiving day, and in the old home sits an aged woman. Her white hair lies in snowy waves upon the broad forehead, as if vainly trying to look into the blue eyes that must once have been lovely. Her wrinkled face is beauiiful with the beauty that one sel- dem sees but on the face of the aged; the inner light of a se- rene spirit that is peacefully and sweetly nearing the borders of the great unknown. and merry laughter of a child has sounded And the solitary on the old hair-cloth sofa, seems but a In the aged woman’s lap is a photograph album at which she gazes long and Looking over her shoulder we see the face of a handsome young man smiling up at us from the book. Large, trustworthy dark eyes we see, and a | manly countenance that tempts us, too, to linger over it. How, then, do we reconcile her murmured words The door opens soitly, but the old lady’s thoughts are so engrossing that she Then a rich, musical voice says softly one word—*‘Mother.” Now the old lady turns with smiling eyes to greet the newcomer, whose face s the counterpart of the one that we have been gazing upon. ““Albert, darling,” she murmurs in a rapt voice, as she rises with outstretched ““Are you dreaming, mother?”’ queries the rich’voice, while the owner places two “It is Willie, mother. Don’t you know me?”’ ingly up into his,fas:e. She seems not to dear. | used to think jyou never would. I have grown \ired of waiting. You will take me with you when you go, won’t vou, dear?” A pitying smile curves the lips that are partly hidden beneath a luxuriant brown | mustache, and the young man whispered to himself: If it is any comfort to her she may think I am father. i will soon come for her, 1 think.” “You will take me with you, Albert?” queried the woman. ““Yes, dear; | will take you with me,’ He ’ answered the man, holding the frail Do Mother was here a while ago, and she surprised when I saw you. Butl am so Put your arms round me again and | will go to sleep as I used to Her voice, dreamily speaking on, grows lower and fainter until she rests her white head on his broad shoulder, and whispers: Don’t forget “Good-night, dear. Her son places the stilled form gently on the sofa, and reverently kisses the ome for you, mother.”” EDITH GRENFELL. A Lasting Faith. The most forcible example of a faith that is lasting ever recorded in the South- west is shown in the history of Captain George Searles of Tombstone. For eight long years he has been working one claim that has never yet returned him a cent. With no other assistance than his own hands, he has alreadv done 1000 feet of work in shafts and drifts. His claim is just pelow Tombstone, quite near the stage road and not far from the tamous Contention mine. His faith is that the rich Contention ledge runs througn his claim, and that ere iong he will strike that ledge and jump in 2 moment from almost a pauper to a millionaire. No one else believes this; but that makes no difference to bim, and every day when he goes down hismine he expects 1o come out a rich man,