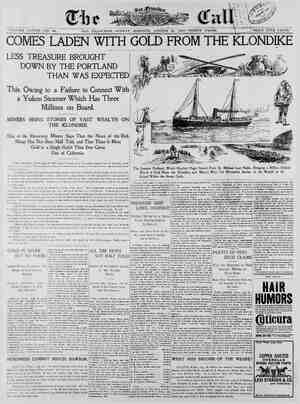

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, August 29, 1897, Page 21

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, AUGUST 29, 1897 21 HOW TO JUDGE LITERARY WORK An Humble Squire in Letters Thinks Some Idle Thoughts About Criticism 1f the following effort of a very humble | squire in letters can put some gallant | ht, armed cap-a-pie and splendidly | ped, on the trail of a noble quest he wiil be more than rewarded; for, in view he tonnage of printed rubbisn that is being dumped on the market, it is time for some literary Hotspur to arise and confound the critics who commend it in | *‘holiday and lady terms.” | Our quarrel with these gentry is incited | by the fact that their criticism consists simply of raising their likes and dislikes into standards, which they expect every one to accept, and for which they can ve no adequate reason, althouch the art criticism is an eminently reasonable one. Personal knowledge of an author— the fact that he is amiable, or the reverse, as a man—the exigencies of *log-rolling” ich are the things that stand for criti- cism with those who do not know or for- get that the latter is an art and hasits | aws like any other art, and who cannot | separate s man’s work from his person- ality. We are prone in these aays to form our opinion of & writer’'s merits from some re- porter's account of his personal habits; whether he has eggs and bacon for break- fast or takes a tub every morning affects our judgment of his literary ability. For how many readers has Froude spoiled the great influence for good of Carlyle by tell- ing us of his dyspepsia ana his bickerings | with Mrs. Carlyle! How many people who found their literary wants fully met by “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” refuse to accord | Lord Byron the praise due to him because | Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe *jumped on” his domestiz reputation! I know an ami- able man who will not read Plato’s *‘Apol- ogy” becanse Socrates is alleged to have ill used Xantippe. A!l these thoughtless people forget that the writer himself is evanescent, and that his work, if it be worthy, alone lives and is substantial. They have never considered, too, that the ilege of uttering thought is mostly ac- ntal, and that the utterer is a mere vehicle of expression—a mere conduit, as | t were, of the things that must be said. What care I whether St. Paul had a thorn in the flesh, or whether he squinted! | He wrote, “Though I speak with the | tongues of men and of angels, and have | rot charity, I am become as sounding | brass or a tinkling cymbal,” and that | Lall suffice me, though I be a pagan. I not concerned with Beethoven’s deaf- ess as I listen to his “Moonlight Son- ata’”; nor with Lord Byron’s clubfoot and amours when he interprets the tre- mendous language of the storm-stricken Aips for my deligat. So. too, cne can enjoy the poems of | Francois Villon, though he was & many- | sided scoundrel; and the naive autobiog- | raphy of Benvenuto OCellini charms us, though he was a self-confessed murderer. there are Chadbands who hold up r hands in hoiy horror at bare men- | | | tion of their names. would be difficult to find anything concerning art than the following age: “Art finds her own perfection ithin and not outside of herself. She is not to be judged by any external standard of resemblance. She is a veil, rather than St:e has flowers that no forests know of, birasthatno woodland possesses. She makes and unmekes many worlds, and can draw the moon from heaven with a scarlet thread. Hers are the ‘forms more real than living man,’ and hers the great archetypes of which things that have existence are but unfinished copies. Na- ture has in her eyes no laws, no uniform- ity. Shecan work miracles at her will, and when she calis monsters from the deep they come. She can bid the almond tree blossom in winter and send the snow upon the ripe corn field. At her word the frost lays its silver finger on the burning mouth of June, and the winged lions creep out from the hollows of the Lydian hills. The dryads peer from the thickets as she passes by, and the brown fauns <mile strangely at her when she comes | near them.” b T. at is taken from Oscar Wilde's ““De- cay of Lying,” and that he was an unut- terable beast does not detract from the merit of his writings, nor dim the brilliance of his epigrams, thank God | For the benefit of those who are unable 10 dissociate the personality of an author from his work, and rate the latter by con- | siderations that belong strictiy to the | former, 1t would be as well toset forth | some of the main principles of criticism, | to enable every one 1o be his own critic, | in a measure. Asking a critic when one’s favorite author is assailed, “Who are you?” or *“What bave you done?”’ or tell- ing him that he is ‘‘sweetly conscious of his own right to criticize,” is beside the point, and on a level with the contro- versial methods of the small boy who thrusts out his tongue at the “other kid.” The following are some of the principles of criticism that have been laid down by “‘competent authority’’: Firstly, that the very essence of crit- icism is comparison, for which the selec- tion of standards is necessary. Secondly, “the critic shouid possess not a correot abstract definition of beauty for the intellect, but a certain kind of tem- perament, the power of being deeply moved by the presence of beautiful ob- jects. Thirdly, a precise knowledge of the meanings of the words that he empioys. Fourthly, an advancement of sound reasons for his opinions. The second principle implies, neces- rily, a hatred of all that is unlovely and mediocre and pretentious. Standards of excellence for the purposes of comparison can be best found among the great writers of antiguity and among our own great English masters of prose and poetry; and no one after reading Matthew Arnold’s opinion concerning the value of a literary touchstone in matters pertaining to criticism would deny the fiicacy of such a method of ascertaining merit. For instance, can your favorite noem by your favorite popular author stand even in the outer courtsof the temple of the following splendid passage from “Measure for Measure” ? Ae, but to die and go we know not where; To lie 1n cold obstruction and to rot; This sensible warm motion to become A kneaded clod, and the delighted spirit To bathe In fiery floods or to reside In thrilling regions of thick-ribbed Ice; T'0 be {mprisoned in the viewless winds And blown with restless violence about | The pendent world; or to be worse than worst Uf those that .awless and uncertain thoughts Imagine howling—'tis too horrible! Orcan it be read without jarring our w £ mirror. {into contact with him. nerves, like a false note in music, after the following noble and most quotable but littie known poem by Henley? Out of the night th covers me— Black as the pit from pole 1o pole— I thank whatever gods may be For my indomitable soul. In the fell clutch of Circumstance I ha’ winced or cried aloud: Under tne bludzeonings of Chance My head is bloody, but unbowed. Beyond this place of wrath and tears Looms but the horror of & shade, And vet the menace of the years Finds and shail find me unafraid, For still, however strait the gate, How charged with punishments the scroll, 1am mas'er of my fate, 1 am captain of my soul. Dare ‘“Intry-Mintry,” or “Little Boy Blue,’” ‘‘baby verses' written in “baby words,” and as such commendinz them- selves to Joaquin Miiler, stand shoulder to shoulder with the passage and poem just guoted in the presence of “‘all-judg- ing Jove?” The other principles enumerated are self-evident and need no demonstration. The following facts are illustrative of the narrowness of view of those lacking critical faculty, and prove further the danger of interfering wita men’s mental provender. With less risk shall you take a b®ne from a hungry bulldog than turn g JW“ T T e TO If it had not been for the guard who paced back and forth along the crest of the hill and a tall masi-like pole that arose straight up ont of the dark-gray sands I should never have known it was a life-saving’ station at all, but would | have'mistaken it for the chosen home of =21 | one who loved the sea. For 1t was sucha | | cozy little house, and from a side window | a baby’s face set in a wreath of golden | curls peered wonderingly ou: at us. The Point Reyes Life-saving Station was four miles farther up the coast than the lighthouse, they told us, but going around by the road 1 am positive it was sixteen, for the way is not traveled much and is rough and the wind that came from the {ocean was damp and chill and a heavy fog hid the jface of the sun. ‘I'he captain, a cheery little man with a military cap and a kindly, hospitable smile on a face as weather-tanned as one can imagine, came down the steps to meet us, and lauched when we spoke of the cold. “*We haven’t seen the sun for a month,” he said. ‘“We hardly ever see it here ex- cepting in the spriny. And he held open the door for us to pass into the cozy little sitting-room. “There isn’t much here,’’ he went on, seating himseli, while the baby climbed on his knee and watchea us from behind the safe shelter of his arm. *“There’s not undiscriminating people from Ella Wheeler Wilcox and E. P. Roe, for every reader of whatsoever caliber has an inner consciousness of his own critical fitness, to which he will cleave after he has left his father and his mother and divorced two wives. A few weeks ago there appeared in a ceriain weekly jonrnal a paper on Eugene Field, in which the writer discussed Field's standing asa poet. Alter admitting his amiability as a man, and his excellence as a newspaper writer, the critic, by the use of the “deadly paraliel,” utterly disposed of Field’s pretensions as a poet ana as a translator of Horace. He was, forthwith, assailed by {two men who had known Field personally, and had loved him—as most people appeared to have done who came One of these de- fenders of Field might be described as “The Man Who Knew Better,” and the other as “The Man Who Must Be Ex- cased.” The former, in the heatof his wrath, arzued illogically that the writer of the article was not in a position to ap- praise Field, because he was not deeply read in American literature. As though one could not pronounce on the flavor of blubber unless one had swallowed a whale! Besides, there is no difference be- tween American and Engiish literature, and there can be none as long as Ameri- cans and Englishmen speak the same language. *The Man Who Must Be Excused” re- sorted to the “who are you?” style of ar- gument, which is extremely effective when the bystanders are also unreasoning and urge their champion to “’eave ’arf a brick at the bioke!” Herewith follows the fable of the “Twa Dogs.”” There can be no excuse for not understanding the Scotch dialect em- ployed, every word of which can be found in the monumental dictionaries now in use and in the glossaries appended to the books of the various Scotch authors, who are enjoying such a vogue th:t they can make money even from the biographies of ‘‘their sisters and their cousins and their aunts.”” I should feel sorry indeed for any one who could not read Mr. Barrie and Ian Maclaren in the original. I, of course, can do so myself, as the following poem will prove; but then there are other mat- ters with more urgent claims to be at- tended to, such as the determination, for instance, of the vexed question long since suggested to me, and which still occupies my leisure hours, whether a gentleman in a frock coat and a Bcotch cap is & greater cad than a gentleman in a jacket and a stovepipe hat. The lifting of the dog by its own tail, as related in the poem, is not original. There are but eighteen original jokes, [ am told, of which all the rest are more or less ille- gitimate descendants. TWA DOGS. Ance—nae langsyne—twa doggies yelpit Aboon a dunghill, where was whelpit, Fu’ mony a tyke; some crept, some skeipit, W1’ spunky tail: These twa were gangin’ to the hellplt Withouten fail. Ane was a dour an’ stuggy doggle WY curly hair an’ brunstase muggy, Wha for the.de'il or ony bogey Cared no a aamn: He barked at gentle or at fogey, Bit boy or lamb. The tither was a bizzin’ fellow, Part pugey, for therest a’ yellow; He thocht his yawpin' was a bellow— ' Puir feckless jackal; He fiuds the Lanes by dint o' smell—Oh, But fthers tak’ all. ‘1 hongh trig an’ sma’ he held your sight, His bounie tail was curled sae tight By selesiecm—it made bim light; And what is mair His hind legs were upliftea quite, An’ pawed the air. An arc light sione the twa aboon, “In ma opeenion ’tis the moon,” Gurled ane—the dour tyke—*let us tune And 8ing herpraises.” The tither doited vee buffoon His yap upraises They yawped an’ gowled, an’ made a racket ‘Wad mak’ the deid cry, “De’il tak’ 11" The neenorhood was fair distrackit ‘W1’ their descantin’: ‘Whate’er they felt they straightway clacket W1 bleth'rin’ chantin’. The Ismp man’s bawtie heard the lngin'— A gangrel tyke wha lo’ed na singin'— ‘A’ frae his warm neuk quick upspringin’, «Hoot, toot! ye loon,” He snashed, “'your clavers cease noo flingin’s Yon's no the moon ” What mair he might ha'e said’s na told; ‘The puggie o’ his leg took hold; Whilst in & smoor o mire they rolled, The tither’s grapple Noo fanged his curple, then, grown bold, 1t grupped kis thrapple. I They haa 1t up, they haa 1t doon, An’ waukit &’ the sleepin’ toun, Till Ben, the lamp man, cam’, an’ soon, W1’ furious pattle, He showed himsel’ upo’ the groun’, An’ won the battle. J. Larrp. Harder Than a Diamond. Within a few days the Patent Office will grant title in a discovery which may fairly be considered as being the most re- markable since the X-ray. It is for a sub- stance that is harder than the diemond, and the inventor is Moissan, the French savant, whose experiments in the line of diamond making by artifice have obtained such wide publicity. The utmost secrecy has been maintained in regard 1o the matter, bat investigation reveals the fact that the substance in question is a carbide of tiianium—tnat is to say, a compound of carbon with the metal titanium. There can be no doubt that its production in quantities will revo- lutionize many industries where abrasives are employed, and it may even be used for the cutting of diamonds. Titanium is one of the most interesting of the rare metais. 1t is about half as heavy as iron, and, like the latter, it is white when perfectly pure. Chemicaily it resembles tin, while in its physical properties it is like iron. The familiar mineral ‘“‘rutile’’ is an oxida of titanium, and is used to give the proper color to artificial teeth. A small quantity of the mineral put into the mixture of tooth enamel produces the peculiar yellowish tint that counterfeits nature so admir- ably. Titanium has no other commercial use than this. There is none of it on the mar- ket in the metallic state, and probably not an ounce could be obtainea at any price by advertising for it. Dealers in rare met- als will quote you gallium at $3000 ar: ounce, rhodium at $112 an ounce, ruthenium at $90 an oance, iridium at $37 an ounce, osmium at $26 an ounce, and palladinm at $24 an ounce; but they have no titanium to sell, because there is no demand for it, and also for the reason that itls ex- tremely difficult to separate from the sub- stances with which itis found combined in nature. Atthe same time there is no doubt that plenty of it conld be produced at a very moderate cost if a large demand should. spring up. Though classed asa rare metal it is not really such, inasmuch as it is a common impurity in iron ores.— Mineral Collector. T Ce—— During Queen Victoria’s late visit to the Ruviera she frequently took tea by the wayside in her long daily rides. One of her Indian servants was sent ahead about half an hour before the royal carriage was to pass a particularly lovely spot, prepared to make the tea as her Majesty likes it. Thus, when the party arrived a little table-like board was laid across the landau and the refreshing meal served with all the accessories. It is estimated that 3000 marriages are daily performed throughoutthe world. much excepting fog and water and mud and a pebbly beach. We never see any one excepting ourselves. It has been a year since any strangers visited us. I don’t mind it so much, but the men find it slow trying to amuse themselves.” “And what do they do?"’ I asked, trying to comprehend what it would mean not to see a new face for a whole year. “Well,” he laughed, ‘‘there are eight of them, and we have drill here, and gzo over to Drakes Bay and drill. They take their turn on guard duty and have some few amusements among themselves. Some of them have picked up collections of peb- bles. You see, the beach is not fine sand, and some beautiful stones have been found here.”” He got up and brought me a large glass bottle from the other side of the room. *'That is one collection,” he said. There were little bits of slipperv hardness streaked and colored as richiy as fancy could paint. “And you found these here?’ I asked. “Those aren't anything,” he replied. “We have iound some beautiful opals. I will get the men to show you their collec- tions after drill.”” And he arose and went out and called the men together. The little boathouse where the life-sav- ing apparatus is kept was so marvelously clean that I lost myself in amazement. There wasn’t a grain of sand on the floor nor a brass locker that didn’t reflect its own brightness, nor an inch of the walls or ceiling that wasn’t shining, and every tool lay at the correct angle in its correct place. The captain stood at the head of the two-wheeled vehicle that held the ap- paratus used for assisting distressed ves- sels at close range. There was a little brass cannon and rope and a strange- looking buoy with an attachment that looked like & pair of diminutive trousers. The men in their white duck suits ranged themselves in line on either side of the cart and recited, as they were asked, the duties they were to perform. [ don’t gnow what they said and I'm not sure that they did either, but it didn’t matter; *that which foliowed was quite intelii- gible. ‘When the last man had finished the last word the doors were flung open, the wagon roiled toward them, and at that moment a great white horse, as immaculate as all the rest, appeared from somewhere and was hitched to tbe shaits. Then away they went, running through the deep sand as for their lives, The little cannon was lifted out of its place by some and dropped into a trench in the sand that had been hurriedly dug by others, while the horse was being led to one side. Straight over the mast-like pole the cannon-ball was fired, carrying with it a light line attached 1o a heavier rope. Oneof the men climted to the top of the pole and fastened the line there, and then began pulling it toward him until the heavier rope and the life-pre- server appeared. Holding on to the rope ALWAYS READY SAVE LIFE The Brave Crew Who Keep Watch at the Point Reyes Station he made a marvelous leap and landed with his two legs correctly in the trousers, a performance that was scarcely graceful nor, I shouid fancy, comforiable, but probably safe. Atany rate the men pulled him down to a position within reach and lifted him out. “Isuppose,” I ventured, “if I wereona ship that was disabled and drifting in to shore, that you would fire that cannon- | ball at the mast and some one would catch the rope and pull it in and fasten it, and I should have to slide down to shore that way ?"” The captain eyed me calmly and laughed and answered, “Just so.’’ “Why,” some oneelse said, ‘‘thatis fun; | goup and try it.” And for reply I looked severe. There area few things I will not do, even to describe them. That is one, and to swing on Mrs. Carter’s curfew beil is another. Total annihilaiion might come in some easier fashion. The old white horse was fastened up again, the ropes and the preservers and the cannon were replaced and slowly we proceeded back azain to watch them put | it all in order. “You see,” explained the captain, “‘each of these ropes has attached to it a small piece of board painted black, with white lettering, telling just where that partic- ular part of the gearing belongs. On one side the directions are in English and on the other side French, for every one on ship board or at the saving stavions is supposed to understand one or both of these lan:uages.” “And suppose they didn’t?” “Well,” he said, ‘“they wouldn’t, then, but they must.” Aud I pondered over that the rest of the way through the sand. “In the winter time it is quite stormy,” I ventured, turning and looking at the uneven beach with ity mass of debris lying where the ocean had tcssed it. Great logs that had tasted the life in a far different clime, bits of wood of strange sorts and shapes, cooking uiensils and the rusted remains of an old siove. “Stormy!” he exclaimed. “Indeed it is in some parts of the winter. The breakers dash in here so wildly that sometimes I wonder that they don’t wash away the buildings. This part of the coast isex- ceedingly dangerous; it is said to be the most dangerous place abont this port. That large boat that you noticed in the boathouse has lost three men just trying to get out from shore. The undercurrent here is tremendous. No map, no matter how good a swimmer, could withe stand it."” *Have you ever been called out?” “No. We went out once, but were not needed. This station has been established for eight years. It seems as though it were an unnecessary expense to the Govern- ment; but strange things happen in such | uncertain places. There might not be a 1 wreck here ever, and there might be need of us to-morrow. We are always ready.”’ “There are stories that I have heara,” he resumed, seating himself on the edge of a log near by, *‘of forbearance and brav- ery, but I don’t think that any captain ever had better or braver men than mine. I think they’d be equal to any emergency. You see that fellow over there winding the rope—the good-looking one?” 1 observed him closely. Tall he was, with finely cut features, and lithe and slender. “He wanted leave to go toone of the towns a number of miles from here some time ago, and I granted it providing he would be back in time to goon duty as guard. He had a wild horse to ride, and coming home, just as he was leaving the town, the horse threw him, breaking his shoulder. If he had gone back toa physi- cian he would bave had to report late, so he rode all the way and got here on time, more dead than alive. Those are the men vou can depend upon. *‘But they are afraid of you girls,”” he laughed. *“I don’t think they’d mind a cannon half as much. They don’t see many women folks.” And we watched with amusement their | nervous haste and conscious manners. “Oh, I wish the whole world was a life« saving station and every man 1n it was brave.’” “It is,” said some one who was inclined to philosophize. ‘People are only brave by contrast. Some are braver than others, of course, and—"" But 1 didr’t hear the rest. I was lostin admiration of the great towering waves that, white-crested, rushed in over the dripping sands, and of the great dark banks of cloud over the sky and of a ship with its feeble little ine of smoke, arising like a protest, as it steamed over the gray- ish-green of the water, looking more like a chil d’s toy in the midst of the vastness than something with a destination in view and a freight of human beings in its keeping. “No wonder these men are brave,”” 1 said aloud, ‘‘with the might of the sea in their eyes and the noise of the sea in their ears always. Now,as for being bashiul —" +Please,” said the voice cf the caprain just behind me, “‘would you like to come in with me and see the collection of pebbles while you are waiting for your companions?’” Ilooked at him and then far up the beach, and saw some wind-tossed gowns and fluttering ribbons, and each accom- panied by a figure in a white duck suit. Only one white-suited brave remained, and he had stopped at the little white- painted guardhouse and was staring with all his might at the moving couples on the sands. ; “I’ll call them back for the other drill if you wish.” But we went straight into the house and looked at the pebbles. MuRIEL BAILET. | The much-used word ‘“boudoir’ really means a sulkery and is derived from the French verb meaning tosu'k. Thackeray had a room in his bouse, upon the door of which wasa sign,"'My Sulkery,”and when« ever that door was locked he was never disturbed. While it is undoubtedly unfair 1o one’s family to sulk in pablic, it may be a good thing to induige in such a mood in solitude, as one is pretty sure to ena in penitence. — There are insects which pass several years in the preparatory states of exist- ence, and finally, when perfect, live but a few hours.