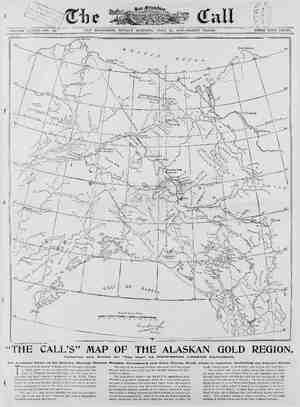

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, July 25, 1897, Page 27

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL. SUNDAY, JULY 25, 27 o It was a plain room with blackboards and charts and queer-looking instruments and a telescope and a great deal of light, 1to which I was shown. *Miss O'Halloran 2’ I asked. She smiled very gravely and bade me be seated and sat down herself on the edge me the while with eyes which have grown used to searching into the secrets of the Leavens, and from which [ dared not Lope to hide uny of mine. “I have always studied astronomy,” she said, speaking in her grave, sweet wav, that has about it a strong touch of diffidenca. “Ican’t say that 1 becan at such and time. I never thought of beginning. Indeed, I never thouzht about it atall, I simply went ahead. There are some minds which grow along one certain I ““With such there is no need to pause and say, ‘I will throw -all other things aside und study this one branch.” It would be foreign to their natures to do otherwise. So it was with me. Ithink thatI life and this study at the same tim might sound absurd to tell of the thoughts and reasonings of a child of 6, but 11 remember them distinctly. I ne ad any training in this branch to speak of. few rules were taught to me at school, the 1nstructor took so littls interest 1n himself and made it so uninteresting to e that it would have tended to discour- age rather than encoura rther study had I not been fixed in my purpose. It is a marvelous study,’’ she went on. “Sometimes when I look up into the heavens I can scarcely remember that there is anything else. It is so great, so vast, 80 awe-inspiring, that you never be- come friendly in a familiar way with f i a further chair and waited, looking at | THE WouEN s«;ENflSTss- EWOMEN EDUCATOR®: =l N lAWYERS’%f i THE ™ (€ +9F WONEN WRITE . WOREN SPEARS: WOMEN OFFicyy .,g Ls, 228y (5, W R i MEN PHipAN rROPISTS 0"MEN ARTISTS. MEN MUSICIANS . could trace on nearly all of them the I name of Miss Rose O'Halloran. She had | followed her love—she had succeeded and | lived in her success. *This is my class- room,” she said, simply turning her back | for a second as she straightened a chair. “1—"" she hesitated a second, and then turned back and faced me. “There is one part of me that must live on e..rth.” I do not know what they call it or | whether it is or not, but as she spoke then I felt that I could see both beings. Truly there seemed to be two beings instead of one, and both with the calm piacid face and the far-seeing eyes and the smiling lips. It may be that her soul has grown s0 used to looking through her eyes into | the neavens that it forgets to betake itself | to its hiding place when the eyes look | down on earth. “One ought not to object to teaching,” | she seid. *‘But it seems like so much lost time. I want to goonallthetime. There; |is a feverish desire within me to keep | delving further and further into the heavens. I don’t believe much in mysti- | cism. Iam very logical; but there is so much mystery in the bLeavens that it | won’t let me rest. I want to understand | ! 1t, ana I don’t like to stop until Ido. “But I have to, and sometimes just at | the time when I want to search the most. It’s a kind of homesick feeling that comes over me, as though I was ont of my native | element; just at that time 1 have 10 teach I know mysell so and explain things that I well, and it seems like wasted time. You see I have just been preparing the board to explain the eclipse—you know"there is an eclipse of the sun this monthb.” She looked doubtfully for a moment at th chalk marks on the board. she said, and then she stopped and smiled. "But I do have a greai dea! of time and I enjoy every second.” And again I fancied that there were two speak- ing to me. “Have you gained all you intended ?” I asked. ure fufil'ed and your ideals intact?” She shook her head slowly. what you mean,” she said thouchtfully, “But it was diff rent some way with me. I didn’t start in at all, you know, an1 therefore I had no conciousness of work- ng for an end. There must be & begin- nend always. [t seems to me « is like winding stairs and soms way the bottom and the top stair meet in infinity. and I have nothing to do with themm. Therefore you see I am only try- ing to climb as many stairs as possible. Ambition? Well, it is just what 1am. Ideals some way don’t fit into the vast- ness, or rather they sink out of sight, for an ideal isa human conception and hu- “It seems—"" | ihose luminaries, they are aiwaye wrapved |y gnity cannot conceive ail the vastness of | in the vast infinity.”’ ‘What a frail littie body she was a3 she and tola me of her life-study. A breath might have blown her away—her physical being could not have withstood 1y shock, and yet there was so inuch strength that you instincdveiy felt. It is in the sweetness of ner mouth and the calm of her face and the clearness of her eves. . “I wonder that you ever come back to eartn,” I s hat you do net keep vour eyes and thoughts up there always.” smiled. *If I should happen to be g up there and had unfortunately sed in the face of an oncoming train > not think I should move. Not that stand there willfully, but I (n't know. Itis almost impossible ing myself back to the realization at there is something I must do here. it must be all one can desire to be'able ) do nothing else but work at that which y love—studving ana searching and Loping and living in their callinz and for- getting everything else. But astronomers sat their aesires,” “But—"" and I did understand, for there was notting about the place to suggest anything but her work or her success. plomas stared down out of their narrow frames, and in spite of the faded ink I the heavens. ‘“‘As for a reward—fame and acknowl- nt from our fellow-beings. We all ed | want that, of course, but still, if that were all there was to work for it wouldn’t be worth the trouble. One loses earthly things almost before they gain them, and the good will of humanity is fickle.” ‘But what do you expect to gain?" I queried. “I don’t know, stair, 1 guess.” “And you have never cared for any- thing but this?” “Well, no,”” she said. “Ic¢ takes a great mind to grasp more than one vast sub- ject. Our finite minds cannot understand well more than one thing. There have been a few men in history who have been distinguished in more than one branch, but they have been so few. “‘Besides, we seldom have a taste for more than one thing. But I wiil tell she said. “The top you”—and I thought she was going to say | “If you'll not tell’”’—*‘I used to write poetry. hahl Oh, it was years ago. | Chronicle and other 2 “Aud you write now? | tirely. I was very fond of writing, but it work. I couldn’tafford to do it.” | »Is it right to sacrifice a talent?” “Are your ambitions in a meas- | “1 know | ; I had about sixteen | seem strangely witbheld from foliowing | poems published in the Argonaut and the | “Oh, no,” she said. “I gave it up en- | ©Oh,” shelaughed, gravely, “1 was no genius and, I think, had little taleat. One should do things well, and if I had to neglect one thing for another I should give up the least important, shouldn’t 1? Anyway, I did,” she added. “May I see your poems?” She brought me three worn and yellow papers of years and years ago. MrIDS EASTWOOD. MQ-:@J » ““You must not tell the dates,’ «I do not mind what else you tell, but on that point I am just a little sensitive.” So I went away with the papers and poems of long agoin my hand and the dreams of the present in my heart. I did not think that she need object to the dates. What did time matter to some souls? But perhaps some day 1 will cut the dates from the papers, too. We are such strange beings in little things. The wind boisterously tore little bits from the paper as I unfoldel it and looked for the poem. In a conspicuous place it was, with “‘written for the Chronicle” at the head and the pathetic title of *Last Days.” In & time of gloom. when the clonds were high, And the days were in shadow passel, There was one that dawned in the sulien sky, And its shade was to be the last. Though the hours were long aud the briars sharp That were strewn on the thorny way, Yel as sweet as strains of a soothing harp Was the thought of the last dark day. With a joy subdued and a tranquil scorn When sflliction is well nigh o'er, We can smile at pain or the cruel thorn That shall torture or sting no more. And agloom is cast on the fairest view Whea fts beauti-s reccae from sight, And the day that parts trom a friendship true Is iInwoven with Lin:s of night. An endearing tone or entrancing lay } 1o hear, est on a farewell day, Can awake but a grieving tear. lis and vales ting gales, Or the angels of light and shade. With the excention of our astronomer | the scientists among the women had all gone away. Some strangers had the pretty litte home of Mrs. J. G. Lemmous at North - Temescal “while she is in the Yosemite getting specimens,’’ they ex- plained. : But there was a strange little room ele- | rom the walls the yellow parchment of | took too much of my time from my other | vated above the house floor, with walls and ceilings of darkly stained wood. And Imera were cones of every size and va- she said. 1 | rlety and species hanging about the walls ! and along the polished beams and from | the ceiling. There was a long table on which were dried specimens that sug- gested to me the name, “This is their herbarium?’ The woman smiled and looked relieved. “Yes, ma'am,” she said; “‘Mrs. Lem- mon has put most of her specimens awsy out of the dust and out of our way, too. She has lots and lots of them. All those drawers over there in the corner are full. They are making a special study of cones, you know, now, and I believe they expect to find some interesting specimens on this trin.” +And they are in the valley ?" I asked. “Qb, no,”’ she said; ‘*‘they are going into | the mountains, in the valley until it got warm enough for them to go higher.” I wished that Mrs. Lemmon had not gone away, but I remembered that her work had been with her husband, and that for years she had been considered one of the first botanists in the State. Miss Eastwood, the curator of botany in | the Academy ot Sciences, was in Colorado. | So they told me at the academy, whither I | went in search ot her. Miss Eastwood’s MISS ROSE HALLORAN They have been waiting | record as a botanist 1is, perhaps, the brightest of any 1n the State, that is as far as women are concerned. She has held her position in the academy for many years and has filed it to the satisfaction of every one. She has found several new species of plants and trees herself, some of which have attracted a great deal of attention outside of the State. Tnere is no one more familiar with the flora of California and no one who has| done more toward ascertaining the rare | species that habit here. Miss Eastwood goes on an expedition all over the State, N A7 AR e (92U /) | ' Miss E/FLEISCHAAN i e CY | ence of one strong mind is felt more searching for specimens. She tramps over the hillsand along the highways and byways and thinks a tramp of twenty- four miles just a few hours’ amusement. She never thinks of riding anywhere un- less she is in too great a hurry to walk. She is thoroughly familiar with the use of the botanical microscope and has pub- lished several pamphiets which have at- tracted universal attention from botan- ists, upon the microscopic coustruction of seeds and piants, and has made excel- lent drawings of celis and tissues that are invaluable. The scientists among the women of this State are fewer than one would imagine until they began' to search for them. There are but two women in the United HStates who are students of ornithology, and they grace the Atiantic Coast. The study of insects has attracted none, and as for reptiles, of course it was not to be expected, and I found on inquiry that there were but three collections of reptiles in the United States. Apparently the masculine mind does not take much more kindly to the wriggling creatures than does the feminine. But I found the only woman who has taken to the serious study of the X ray. She has a pretty little room on Sutter street with the woman’s touch showing plainly in the lace curtains over the door and the hall full of weird pic- tures of live men’s bones. Miss Fleishman asked meip.and showed me her machine and how she took the photographs of the inner bones. And then she stood in front of the machine and gave me the plates and bade me look at her ribs and spinal column and lungs | and heart, and then she held it up to her face and showed me the skull. “Do you like it?” I asked. ““Electricity is the most fascinating, the most wonderful thing, that ever was be- yond man’s comprehension. 1t is so in- teresting that when I get to reading and experimenting I forgot everything else.” She pointed to a pile of borks—formid- able-looking volumes, which show clear | through the bindings that there is very | little paragraphing—and lifted one of | them to her lap. **You don’t know how I enjoy it. I do not understand why more women have notundertaken it. Of course there are difficulties; so there are in everything, but the pleasure of it ont- weighs all else.” “Qf course,” she went on, ““I have only the least bit of knowledge—only just begun on the subject. It is so vast that one gets just a bit discouraged at the out- set, and still not any more so than in any deep study. It all looks unfathomable in the beginning.” There are few women in science, and yet some way they seemed like a great number. Perhaps it is because the pres- | ergy. | of which the lecturer gave | an imaginary picture forcibly than a great number of others, and that the few strong women will answer for an army. MurieL Barny. The Gymnastics of Rest. The Edinburgh health lectnre was de- livered by Dr. George R. Wilson, medical superintendent Mavisbank Asylum, on “The Gymnastics of Rest.” He said 1t was the unfortunate habit of our tmes to measure the welfare of the people only by their material prosperity, and to ignore their mental distress. The waste of human material was greater than ever, the tear and wear of men’s minds increased, and now, in spite of all our in- ventions, nay, because of all our inven- tions, the world was more than ever in need of rest. The nervous system was contrived so as to thrive in an atmosphere of mild impressions, not in one of con- stant shocks and jars. True, we could become accommodated to shocks, to noise and din, but we became accom- modated to them only by usiug up en- It would repay us to get away from noise and din even for a short time. Just as noise was to the ear dinginess and the dull gray atmosphere of cities were to the eye; our eyes and our brains were adapted for richer colors than the life of cities afforded. There was, perhaps, a greater evil which city life brought upon the eye. The eye itself, and its nerves and muscles, was so conceived that in the natural state, in the state of rest, we looked at a distance, but by constantly looking at objects close at hand we never gave the eye rest. It was not easy for older people to learn new ways, but children should be taught whenever a glimpse of distance could be had 1o let loose their eyes upen it, to turn to the horizon and rest. One of the first steps to mental rest was the ability to per- form the feat—as to the acquirement some in- teresting hints—of looking at a dis- tance when there was no distance to look at, and resting the eye on of the hori- zon. A second step toward rest was the relaxation of that tension in the muscles round the eye, and especially in the muscles of the forehead, which char- acterized men of the city, and busy men everywhere, when they were attending intently to something they considcred important. A third step was the teach- ing of the muscles round tha mouth to “stand at ease” rather than ‘‘at at- tention.” This threefold process he called “expansion of the attention.” It was a mistake to suppose that this whole subject was stupid; nothing was more evi- dent in this bustling age than that most men and women had not the most remote notions of keeping their minds at rest. In play and at work alike we were “pressing,” to use an expression irom the language of golf, nearly all the time, anxious minded and strained. Passing on to the subject of “hurry,”” the lecturer noted that there was a world of difference between promptness or quickness and hurry. The difference was that when we hurried we were anxious minded—we were “‘pressing”; and the ex- cessive tension disordered our activities. Next, speaking of the panic, the lectu- rer cffered various hints for ‘squander- ing the attention’’ by way of mini- mizing the effect of shocks. losely aliied to panic, but more lasiing, mora chronic, was the vice of the mind which we cailed worry. Worry was an inability to withdraw the attention from unpleasantness. It was a vice which was rampant among us—a most repre- | hensible vice, because so unnecessary and so easily evaded. If we practiced what he had called the gymnastics of rest we wou!d never worry. We would feel pain and dis- tress often enough, but our mind would not dwell on the feeling of them.—Scots- man. e Taore than 30,000 specimens of fossil in- sects have been collected from various portions of the world. Of these the rareat are the butterflies, less than twenty speci- mens having been found. THE DEATHKNELL OF MORGANATIC MARRIAGES IS SOUNDED Little by little the sovsreign houses of the Old World are being divested of those medieval and anachronic prerogatives that were all very well when people were | willing to admit the extravagant claims of mundane royalty to cousinship with the Almighty, but which are thoroughly out of keeping with the enlightened and progressive spirit of the present age. One of the most preposterous of all these ex- traordinary privilezes has been that of morganatic marriage, a form of matri- monial ailiance but little understood here in the United States. Based upon the princivle that an ordinary union was im- possible between the memberof areign- ing family and a person of minor rank helonging either to the nobiiity or to the people, it has been considered binding only on the inferior of the two parties, but not on the superior, who, ecclesiasti- cally and legally, has been held free to contract another union without first get- tine rid of the morganatic partner. The latter has been debarred from shar- ing the social status, title or privileges of the more high born of the two, and the issue of the union has been usually sub- jected to similar disadvantages. Of course the existence of an institution of this characfer implied a sort of obligation upon members of sovereign or media- \ lized houses not to contractany but mor- ganatic marriages with people of & lower grade of sociely, and this has no doubt sufficed to prevent many a union between American heiresses and impecuniots German princes, Morganatic marriages may be consid- ered to nave bad their day, for it is their | deathknell that has been sounded by the | judgmeént just rendered in the Lippe Dat- | mold succession controversy by a spe- cially organ'zed grand tribunal presided | over by the venerable King of Saxony, | dean in point of ave of the sovereigns { comprised in the federation known as the | German Empire. According to the deci- | sion of this court, the highest in the land, and the decrees of which by previous | agreement are binding upon all the States | of the empire, morganatic unions on the part of parents or of more remote ances- | tors are no longer to constitute any bar to the succession to the throne. This being | the case it naturally follows that they cease to entail any di-qualifying conse- quences in all other particulars which are naturally of minor importance and be- | come identical with ordinary marriages. | | The controversy, which has been exciting an immense amount of interest throughout Europe, may be said to have originated with-Emperor William, and in the following manner: Two years ago ‘Waldemar, the then reigning I’rince of ‘Lipmeutmold, being in failing health, bodily as well as mentally, and having no heir but bis lunatic brother Alexander, was induced by the Emperor to draw up a will according to which the regency of the throne auring its occupancy by the insane Prince Alexander was to be vested, not in the hands of Count Ernest of Lippe, the nearest agnate or closest relative, but in tho-e of an infinitely more re- mote kinsman, namely, Prince Adol- phus of Lippe-Schaumburg, who, how- ever, enjoys the advantage of being the most subservient and therefore higaly favored of the brothers-in-law of the Kuiser. Prince Waldemar moreover ex- pressed the hope in this precious will, which he had not the vestige of a right to make, that the regency would only be pre- paratory to the Adolphus to the throne on the demise of the present lunatic nrince. On the strength of this will, as soon as ever Prince Waldemar bresthed his [ast, Adolphus took up his residence at the palace, seized hold of the reins of the government and caused the principality to be militarily occupied by ‘a strong de- tachment of the Prussian troobs of his brother-in-law, Emperor William, the presence of the soldiers effectually quell- ing all projects of resistance on the part of the indignant population. Indeed, he actually ciose | the doors of the palace in the face of Count Ernest of Lippe and his two sons, the nearest surviving kinsmen of the dead ruler, when they arrived to altend the obsequies, and would not ac- cord to them any place among the royal and princely procession of mourners, con- duct which excited so much public resent- ment that the legislature of the princi- pality, through its president, requested the universally respected ana popular count and his two sons to walk at the head of the pariiamentary representatives and to sit among them in the church, where the services over the remains were celeorated. Count Ernest von Lippe, as any one who examines the pages of the Almanach de Gotha will perceive, stands in point of relationship nearest to the present de- mented Pripce, and as such isentitled to succession of Prince | the regency, as well as the eventual suc- | | cession to the throne, This right, warmly | indorsed by the Parliament of Lippe, by | the municipality of Detmold, by the en- | tir: population of the principality, as| well as by all the non-Prussian states of | the German empire, was contested by Em- peror William and by Prince Adolphus on the ground that Prince Ernest was de- barred from the prerogatives which he would otherwise have enjoyed by reason of his being descended from a great-great- grandfather, who instead of marrying a woman of his own rank had contracted what is known as a morganatic alliance. It would ke only in the event of Count Lippe, his sons, his brothers and his nepbews, all alike descended from this non-prineely ancestress being placed out of running, that the infinitely more dis- tanily related families of Schaumburg- Lippe: would have any rights to the succession, Prince Adolphus, I may add, is merely the younger of tive sons of the reigning Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe. Fortunately for Connt Ernest Lippe the high-handed ana arbitrary proceedings at Detmold, and particularly the indignities towhici he had been subjected by Prince Adolphus at the funeral, excited 8o much indigration throughout all the other non- Prussian States that Emperor William became very seriousiy alarmed, all the more as he himself was held responsible for the whole affair, his brother-in-law being looked upon merely as an instru- ment in his hands The Bavarian ard Wurtemberg newspapers were quick to point out that if s things were toler- ated at Detmold none of the sovereign States of the confederation wouid be safe from analogousencroachments by Prussia upon their independencs. Finally the ouicry became so loud that Emperor Wil- liam suzgested the policy of submitting the rival rights to the regency of Prince Adolphus and of Count Lippe to a tribu- nal consisting of the highest judicial au- thorities of the Empire, presided over for the occasion by the King of Saxony, the senior in point of age of the federal sov- ereigns. The tribunal has now rendered the ver- dict, which is entirely in favor of Count Lippe, who by virtue thereof has become regent of the principality, the administra- tor of the vast property of thereigning House of Lippe-Detmold, and the next heir to the throne, which, in the natural order of events, cannot mnuch longer be retained by the now septuagenarian and demented Prince. Prince Adolphus was given twenty-four hours in which to va- cate the position which he had usurped. The tribunal could not logically come | to any other conclusion. For if morgaun- atic alliances on the part of ancestors had been pronounced sufficient to disqualify from the succession to the crown, and had Count Ernest of Lippe’s claims been held invalid, it would have been equivalent to a judicial declaration thal at least seven-tenths of the thrones of Ger- many were held wrongfully, first and foremost that of the Grand Duke of Baden (married to the only daughter of oid Em- peror William and a granduncle, there- fore, of the present Kaiser), whose grand- mother was a mere actress, created, after her morganatic marriage with the Grand Duke of the day, first of all Baroness Geyer and then Countess of Hochbere. Inaeed there is a question whether if Emperor Will:am’s argument had been admitted his own children could have been permitted to succeed to the throne of Prussia. Morganatic marriages are regarded by | many in this country in the light of some- | thing immoral. This is far from beingi the case. The position of a morganatic wife is perfectly respectable. Her union receives the sanction and the blessing | of the church, and the only way in which it differs from an ordinary mar- riage is that the left instead of the right | hand is given before the altar, and that as stated above the rights of the inferior of two contracting parties are limited. Indeed, the word ‘“‘morganatic,” derived from the Scandinavian verb, ‘‘morgyan’ | (to limit), implies as much. The people who until now have been permitted to contract morganatic mar- riages and to assign so altogether unjust a status to their wives and to their children have been not ‘only the princes and princesses of the now reigning houses | of Germany, Italy, Austria, Russia, Den- ‘ mark, Spain and Portugal, but also the members of what are known as the medi- atized families of Central Europe.. These fizure in part Tl of the Almanach de Gotha. The heads of these houses, some of them dukes, some princes, others merely marquises and counts (such as for instance Count Pappenheim, who married Miss Wheeler of Philadel- phia), formerly enjoyed the rank and power of petly sovereigns, vassals. however, to his Apostolic Mujesty, the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire at Vienna. The Napoleonic wars swept the majority of these small states away, and the treaty of Vienna set its seal to their disappearance. It was felt, bowever, that | they required some sort of compensation for the !oss of their dominions. Accordingly they and their lineal des- cendants were invested with a number of extraord nary privileges, such as are en- joyed by the members of actually reigning bouses, and conspicuous among which was the right to contract morganatic mar- riages. These unions, as stated above, are entirely out of keeping with the demo- cratic spirit of the present age, and are not appropriate to the conditions of modern hife. They are no longer tolerated by French law, which regards all marriages as equally binding upon both parties, the fail- ure of M!le. de Clinchamps to assume the title of her husband, the late Duc d’Au- male, who has bequeathed the bulk of bis enormous fortune to her son, being en- tirely due to a private agreement between them. The King of Saxony aud his fellow judges, constituting as they do a court, the supremacy of which is acknowledged by Emperor William and by all the sover- -e¢ign familiés and states of Germany, have now adepted the sensible French view and declared that left-handed marriages can no longer be regarded as a bar to suc- cession of the throne, ergo that they were just as valid, as binding and as complete as ordinary matrimonial alliances. This 1s equivalent to the deathknell of the morganalic marrizage system. Ex-AtTACHE.