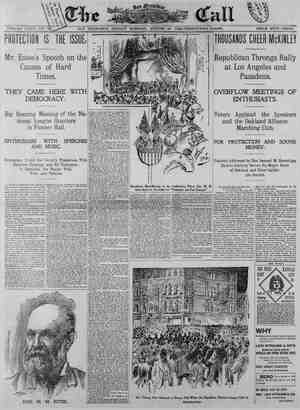

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, August 30, 1896, Page 25

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, .SUNDAY, AUGUST 30. 1896. 25 And this was Texas’ story. He began: I have bad some pretty close calls in my lite, but the closest of all, the one time when I thought my last moment had come, was in Mexico. 1 haa been in that eountry several weeks, passing from one small town to another, but as all my social and business intercourse was with English- speaking people my acquaintance with the Spanish tongue was limited to a few phrases picked up here and ther: [ arrived in San Ramon about sundown. San Ramon was the last town to be passed through. From here I was to be driven across the bor- der and | expected to be in Texas the next morning, and then, heigh-ho, for Dallas and home. San Ramon bad a hard reputation—was, in fact, nown to be one of the worst little towns of all those infamous border tlements. Perhaps it was foolbardy to venture there, being not merely a-stranger and alone, but carrying on my person my modest earningsina leathern belt. Possessing a dangerously hot temper I have never made ita practice to carry firearms, especially in that country where ccur‘oi justice are dispensed with and the man who kills a Mexican may expect no clemency I.trusted to my own discretion to keep away from all possible mischief. My first official action was to decline the kind and urgent invitation of a villainous-looking fellow-traveler to dine with him. The alluring picture he painted of his home, the dark-eyed wife and daughter, the low, cool adcbe dining-room, etc., had no charms for me. He bade me an affectionate and regretful farewell, and I breathed more easily when he departed. e . The day had been long and hot. At the so-called hotel I found but poor facilities for washing, and to further my discomfiture the dinner would not be ready for yet an hour. Sitting alone on the porch in the deepening twilight a great home sickness came over me, I thought of all my past life, old days, old iriends—of my mother and the girl. I was now at last going home to marry; and in the midst of this tender reverie came the great fear that I might never see them again. As never before in all my long weeks’ sojourn in Mexico [ realized 1n what a desperate situation I had placed myseif and how precious was my life to me. Perhapsit was the sight of a passing low-browed half-breed that made me regret the absence of firearms. As I rose to answer the dinner- call I firmly resolved to possess myself of a weapon before I undertook the drive to the border line. A pleasant surprise awaited me at the dinner-table. Aside from an exceptionally good spread I found a white man, as 1 called him, a young American telegraph operator, who bad just arrived from San Juan under the protection of & native guide and interpreter. We hailed each other as brothers who meet in a foreign land and under ihe influence of jovial companionship and some of the bemign-faced landlord’s vintage my nervousness evaporated like a mist. He had expected to spend the night atSan Ramon and drive (the distance is about ten miles) to the border line the next afternoon and thence take the train to Dallas on the follow- ing morning. “But,” e said, “if it can be done sooner I will gladly change my plans and accompany you. To tell you the truth (lowering his voice), [ am anxious to get rid of this guide, whom 1 strongty distrust. T’ve been beastly uncomiortable the whole trip. I can’t speak a word of Spanish, and I know his interpretations are half falee. He is in league with every low-lived ruffian in the country.” After dinner and & pleasant smoke on the piazza we scored with the proprietor and shouldersd our slender luggage. The ]mdlord was ill- pleased with me for taking away his guest,whom he had intended to cinch well, and the guide took his dinner with an ugly grin. “Here!” I cried, calling him back as he was slinking down the narrow street, “‘find a team to take us over,” and he dexterously caught the coin in his teeth and disappeared. “Will he do it ?'’ asked the operator. n alre?'gee:fig‘h us the trouble of searching for one, though in truth one would not be difficult to find. And as for m:’stlng him—it means to hima i m the driver, so have no fear. coméuu]rs:‘:zoi:)gh before ten minutes had elapsed he drove up with a sturdy, comfortable conveyance. The driver was no exception to the rest of the ruffians. I thought to please him with drinks and cigarettes, but it was evidently no more than he expected. There was but littie delay and then we started. The guide bad disappeared in that peculiar fashion com- mon to the greasers, a trick that makes one start at every sound. The operator and I were both silent. We were esch thinking of home. The mules were going at & slow gait. The town seemea rather large, and I presently suspected that we had driven on a certain street more than once. The operator was still wrapped in thought and had not noticed it. I said pothing, but kept very much on the alert. I mw_amly cuned' my negli- gence in not providing firearms, but observed with great relief that our driver was also unarmed. Presently we reached a low quarter of the town. ¢TI thought you had the team 1t was too late to Dwelling on the Botderland Of Insanity and Suicide 2y o County, Cal, Aug. 13, 896, Editor San Francisco “Call”—Dear Sir: The writer (69 years of age) has been afflicted with a nervous disease for four years past and has been bedfast for twenty months. I have tried some of the best physicians in San Francisco, San Jose, Sacramento and other places without getting re- lif. Physicians prescribed morphia about two years and a half ago, which I have been taking ever since. And now it is affecting my brain so that I cannot sleep, and I am told that I shall soon become insane. I have read in “The Call” of the last few days opinions as to whether suicide is justifiable in a person in my condition. I suffer terribly and all medicine makes my brain worse. I want your opinion in “The Daily Call” as soon as convenient. Please don’t publish my name or address (it is on your subscrip- tion-books). I am taking two grains and a half of morphia per day. Respectfully yours, Subscriber. - Since the writer of thjs letter signed his name and address apparently in good faith, it is only fair to withhold them, as requestedsand accept the letter at its face value. Possibly the name given does not represent a real person, but that the circumstances set forthdo describe about the conditions under which a very large percentage of all the suicides are com- mitted no observing person will deny. And berein is involved the whole question of suicide. There is no real difference of opinion as to the justification for or the morality or the -utjlity of taking one’s life exc-pt under circumstances similar to those so described—circumstances wherein the sufferer of either mental or physical torture bhas lost all hope this side the line that divides time from eternity. When sach a case is presented to the humanitarian whose logic does not carry him beyond the surface of things he snswers—quite hon- estly from his standpoint—that it is better to die. But [ believe that his standpoint is sadly erroneous and the agony of {he sufferer who follows his advice vastly increased. If nature 1s just and life bas any meaning at all, the greatest sufferer the sun ever shone 1pon cannot better himself by forestalling the death that would otherwise come to him in nature’s own time. ‘Who takes his own life br«n.n alaw of nature. And what 1s there in logie, in common-sease, in religion or.in philesophy to lead one to betieve that he can escape the penalty of an in- fraction of a natural law ? : 2 . One may cry aloud that nothing can increase h}s tortures, since they have reahed the limit of mind’s or matter’s capacity to suffer. But his agonies may be pralonged! : D Not forever, for that is against logic—unless one has already accepted e dogma of eternal damnation. But why should a forced and unnatural death be supposed to end the tortures? Is :herg anything in all nnurovto suggest that the infraction of one natural law will cure the effect of a prior i ion? - fr;_c;eosmpu“ rules of logic and common-sense ungh; to be nflich_n_t to prove not alone the futility butaiso the monstrously evil effects of suicide. Neither the priest nor the philosopher is needed so much these days, I think, as a little clear and logical thought. Look to the world about you. Is it not governed by the law of cause and effect? 1f you place your hand on the hot stove there will be pain. By chopping off the arm you may escape tbe burn on the hand. Thisis the logicof him who believes suicide can be justified—he would chop off the arm to escape the burn. Using everyday business reason, however, we do not amputate the arm until it becomes necessary to do s0 in order to save the life. ‘The entire universe is ruled by this wonderful and yet quite common- place law of cause and effect, Were this law suspended for a single in- stant the universe itself would collapse. Science teaches this and demon- strates it in a million eifferent ways, while human reason proves it beyond all possibility of contradiction. We can peither lift a finger nor think a thought without the aid of this law of caunse and effect. 1t is axiomatic that nothing comes from nothing. There is a cause behind everything. The Absolute itself is beyond the comprehension of man, but everything this side the Abvsolute has a cause. So it happens that even human suffering has a cause, whether it be mental or physical suffering or both. We see and feel the effects, but often the real cause reaches too far back for us to trace it. Yet the cause exists, In the thoughtless egotism or joy or grief we act often as though we expected this Jaw to stand asmde for us. When passion surges we forget its operation. Bat sball we say, when calmly reasoning, that we are greater than nature and can set aside her laws? But we must either say this or else admic that, *given a cause the effect will follow,” and no power in heaven or earth can or will stay itin order to permit usto escape the effect. Tt is difficult, I know, for one to see the justice of this law sometimes, particularly when it falls with force upon ourselves. But are we to deny it simply for that? TUsually, when we see its operation upon others it is not so difficult to believe that the suffering is needed or deserved, or, at all events, beneficial. Is it hard to believe that nature has no limitations, while we have many? Her operations are very intricate; we cannot see them all. It is true, I believe, that to see broadly the justness of this governing-law one shoula know something of that ancient system of philosophy which taught the reincarnation of man upon this earth for many successive lives. With such a philosophy one realizes the “‘eternal fitness of things” in the universe, and even the eternal justness of the law of cause and effect when ourselves are suffering the effects. But the tormented man, dwelling on the borderland of insanity and suicide, will not be likely to consider even the fundamental principles of a system of philosophy before acting. Nor is it absolutely necessary that he should. He has only to ask himself whether he is greater than nature and can hope to either escape the effect of a cause already in motion before the effect has died in its own natural way, or can break a law of nature and escape the penalty. There is but one answer to such a ques- tion. Yet it an effect cannot be escaped it can and will be outlived. Unless this thing within us that thinks and knows ceases its existence with the body—a supposition that no one seriously holds 1 this day—then there is no reason in all common-sense why any man should lose hope entirely. Experience and logic alike prove to usthat we can set in motion no causes which are everlasting. In order to keep on suffering throughout eternity one would have to keep on breaking natural laws eternally. If we burn our hand, the pain dies away as soon as nature has re- paired the wrong we did. Nature is kind. She goes about repairing all our wrongs as fast as her keen sense of exact justice will permit. There are some physical pains that last longer than others, some mental agonies tnat die out more slowly than others. But ail effects do cease. Exper- ence and reason show this. Man, being finite, cannot set in motion an infinite cause. ’ _And suppose the effect—the pain ard the agony—last a lifetime? ‘There is still an eternity of lifetimes beyond. When death comes natur- ally death ends the *‘ills that flesh is heir to.” Visible proof cannot be brought for this statement, it is true—nor can the vibrations of the ether about us be seen. To a thinking, reasoning animal there is higher proof than can be sensed. But who can tell the writer of this letter, the man who expects to be- come insane from his sufferings, what to do? Here is a task for a near-by friend who has an ounce of common-sease and a pound of human sympa- thy to spare. A distant writer can only vaguely sugeest the concrete. However, doc- tors bave before this predicted dire results that have never come to pass, and the power of the human willisa thing to conjure with. Doubtless the man who thinks much of approaching insanity, or any other ill, especially a mental one, thereby increases the danger if not actually produces the thing itself. Resolve not to become insane. Resolve to remain in control of your reason in spite of all. One can think the kind of thoughts he wills to think. Think peaceful thoughts, hopeful thouzits, harmori- ous thoughts. These will help. They must help, for every cause has its effect. Hope is the word, not despair. Hope is true; despair is false. Every effort counts, even though immediate failure mm; to follow. Sufe fering brings wisdom and wisdom is lasting, and the grave is not the end. : i ¢ Jaxzs H. GriFrss. That Remarkable Case of Deathlike Trance in Portland The remarkable case of Mrs. Mary S. Albertson, who, as stated in & telegram to THE CALL from Portland, Or., a few days ago, had been twice rescued from s deathlike trance by the use of a galvanic battery and other restoratives, is but one of a rapidly increasing number of phsychical phe- nomena for which our modern science affords no explanation. For many years the necessity for explanation was neatly evaded by a denial of the facts. Science assured us that the laws of nature made them impossible. Of what use, then, to investigate facts that could not be? Why trouble ourselves about cases thatonly seemed to be genuine, but which, according to all the laws of logic must have been due to some hocus-pocus that was simply clever enough to deceive our senses? Conse- quently, no matter what the evidence might be, or how reliable the wit- nesses, an adverse decision in advance discouraged all investigation. But a flood of queer happenings cannot be pooh-poohed out of exist- ence any more than a disease can be ignored when it becomes epidemiec. However unwilling we may be to believe that Dame Nature still has sur- prises 1n store for us, or to admit that we in this enlightened nineteenth century still stand confounded before the mysteries of our own human constitation, it is no longer possible to deny that there are facts connected with the mind or soul of man which are not explainable by any mechan- ical theory. Nor can we afford to ignore facts related to our immediate welfare by the light they throw on problems of mental and physical dis- orders. Indeed, the single danger of being buried alive while in a trance condition is enough to make g:eater knowleage of such states exceedingly desirable. 3 Though modern science has not yet investigated these realms of mys- tery there was an ancient science which did so. It had the merit, too, of actually explaining, and without any evasion, ail these psychological problems. If any justification were needed for its presentation in these latter days, surely we may fina it in this fact. At least, in the absence of any other theory it is worth considering. The ancients did not say man had a soul, they said he was a soul. They viewed the soul, not the body, as the real man, and looked upon his phbysical form as a temporary instrument in which he was destined to work out a part of his necessary evolution. For the unregenerate man the body was a prison; for the purified man, a temple. It is unsatisfied desire, they said, that holds the soul ito its flesh. These desires are an acting force that creates for the mind out of thought-stuff an ethereal body which dwells within the physical body and serves as a link between it and the mind, or thinker. : This astral body, as it is called, is the real seat of thought, of desire and of sensation, These appear to belong to the body because they are confined to it during its periods of wakefulness and also because so many of our thoughts and desires are interwoven with physical concerns. But were the boedy to be dissolved the astral form would still remain, and in it the old thoughts and desires wonld continue. Sleep has been poe tically callea the twin brother of death, and er- tainly there is an analogy between the two states. In one, as in the other, the senses are at rest and consciousness is withdrawn from objective concerns to subjective states. The soul ceases to have experience in the body. It is absorbed in its memories, its ideas, its longings. But the dreamer lives on. 1f his dream life is less rational than the waking one it is simply because his ethereal form, which develops much more slowly than the physical, is not yet so highly evolved, and is therefore a less perfect vehicle for thought. This does not prevent it from being a far more sensitive vehicle of perception. For this reason, though we think badly in sleep, we often catch ideas or impressions that are finer than any which come to us in waking hours. While sleep is a normal mode of sinking into the subjective state for rest, trance is abnormal. It has a closer resemblance to death. Not only -forms of its dear ones. in this condition is the mind withdrawn from outward activity, but the vignl functions also become impaired. Vitality slips away, leaving so faint a spark in the motionless form as to make it appear dead. Granting the existence of soul as an independent life, not a mere aroma of the brain, it1s quite logical to assume that it would enjoy still greater freedom in the trance than in the sleeping state. Cessation of physical functions snaps another cord which binds it to its prison, for no bodily sensation can then affect it. Mind is free to wander in its thought world, to feast on happy memories, and to create in imagination the Consequently, its life is a continuance of the past, plus a realization of its aesires. But there is infinite gradation in subjective states. All minds are not alike, nor are all 'subjects in a trance state able to enjoy the same condi- tion. There are mental passions ‘as powerful to bind the soul as are any bodily desires. The miser hugs his gold even when his fingers have relaxed their grip. The selfish man pursues, on his mimic stage, his schemes for power or pleasure. The hater clings to visions of malice or revenge. Briefly, the mind continues to act its accustomed part. In these casesthe entranced person is not aware of Lis condition, but like one in sleep, is oblivious to outward things. For this reason he be- lieves himself to be 1n action as before. In fact, it is a profoundar sleep that has falien upon him, one so akin to death that those who have been brought out of it may well claim that they have been ‘“‘on the other side.” That is, on the threshold of ‘‘the other side,” for slipping the body’s leash is not all there is of death. As its experience does not cease, the soul is gradually purged of its passions. Fresh incentives to desire are not furnished by the subjective state, as they are by this world; hence, when old impressions are effaced the soul becomes pure. That is, the thinker ceases to be affected by passions of any kind. It becomes able to live in & realm of thought over which no desire can again bring cloud of longing or discontent. Safein its own ‘‘home” the thinker is blest. In its perfection this condition is what we call heaven. Some ancient phil- osophers called it devachan, the ‘*‘region of the gods,” those “islands of the blessed” which man might visit even during earthly existence were his soul pure enough to pass their crystal portal, It is said that some of the purer souls do in trance reach to that lofty consciousness, enjoying there a more vivid and blissful existence than human minds can conceive. Although it is not possible for most of us to verify this statement, it is consistent with the theory of soul that is under consideration. and explains the beatific visions occasionally testified to by those who have been antranced. In other cases, when the subjects know what is going on around them but are unable to move or otherwise to make the fact of their con- sciousness known to others, it would seem that the derangement is in the physical rather than in the psychical nature. Instead of consciousness being drifted into other states, it is the body that fails to respond to men- tal action. Health, whether mental, moral or physical, demands that due propor- tion be maintained between the various factors of our complex being. It there is need that reason should govern the.body, there is equal need that it should direct the astral or psychic nature. This is being rapidly unfolded by the evolution of our race. Chiefly because it is so little under- stood the curious are more eager to hasten its development than to learn how tocontrol it. This is the chiefreason why ancient philosophy has been revived in the West during the closing years of this century. Psychic changes are inevitable, but they may be intelligently guided. So long as intellectual and moral progress keep the lead we are assured by philos. ophy and by experience that the evolunon of psychic faculties may be accomplished without any sacrifice of mental or physical health. Mercie M. THIRDS. turn back now. The best course was silence and trust in divine Provi- dence. 1 expected every moment we would be assaulted. Strangers are aiways snspected of having money or valuables, and the border greasers first kill their man and then rob him, We stopped at an ill-lighted but well-patroniged saloon. Our driver-dismounted and entered it. I determined to make a bold fight for life if necessary. The operator was pale with terror. He fully expected to be'murdered. I was wet with perspiration, but set my teeth firmly and we both watched the door. Had I dared I would have seized the reins and driven on, but tnere were a dozen skulkers on the street who would have stopped it and shot us like dogs. After five minutes, which seemed like five years, the driver reappeared with a ccmpanion, bota buckling on’six-shooters. *Why this delay ?”’ I asked in a forced tone of impatience. “The moon, senor,” he answered. “We must wait for the moon, which just rises.” The mules broke into a trot and we soon cleared the town. I felt we -were in a bad position, indeed, but I hope I shall never againste 2 man as ‘frightened as the operator was. I myse!f thought my last hoar had come. The roaa was easy and open but several miles abead it broke into the mountains. The greasers spoke but litile to each other. I determined at their first suspicious movement to reach forward and endeavor to possess the assistant driver’s weapon, which was quite within my reach. A dark clump of trees appeared ahead. “They will murder us there,” T thought, and strained to keep my seli-possession and coolness. We approached nearer and nearer until the dark shadow fell' upon the mules’ heads, and then on the driver's, and then upon my trembling companion and myself. ‘We drove on in the shadow—a little more slowly, I thought. Beyond the trees I saw the road again open, with the bright moonlight streaming npon it, and again I resolved not to die like adog. An abrupt halt and the driver leaped out, his revolver in his hand. The operator grasped my arm convulsively. His face was pallid even in the shadow. I leaned forward slightly, cne hand on the operator’s knee and one ready to spring at the uncovered firearm in the seated man’s pocket. He was holding the reins, and I calculated my apparently unex- pected movement would startle him, which gave a possibility of his drop- ping the lines and the mules starting to run. In this confusion there might be a chance for us. The hait and the driver's action were sudden, but before he had time {0 turn “Quentienes?’ (What is the matter) I called out sharply. There was no answer. 1 saw him raise the gleaming steel, and simul- taneously with the report Isprang on the second driver. Theshot whizzed by my ear and with a groan the operator fell to the bottom of the convey- ance. The attackea driver, before I could grasp his weapon, dropped the reins and turned quickly in defense, and the startled mules bounded off. Then we grappled for fully three minutes, the pistol still in his hip-pocket. 1 felt his hot, mescal-fumed breath upon my cheek, and he made desperate attempts to use his teeth. He was natarally the stronger of the two, but liquor had stolen his strength, and just as I felt I was lost his grasp weakened, and with one herculean effort I flung him from the flying vehicle. Saved! But for how long, I wondered. I thought the operator was dying and every moment expected we would be dashed to pieces. It was impossible to seize the reins. All I coutd do was to clutch my companion with one hand and with the other try to keep from being thrown out of the swaying wagon; and building on the wild supvposition that we reached the town before we were exhausted, what but a Iynching rope awaited me, for the greaser’s wagon was well known on the road. Another lurch and something hard _struck my foot. I bentforward and picked up the loaded six-shooter. Alas! Of whag use was it to me row? I might blow my brains out, I reflected. It ouly offered me a little variety in the choice of death. I raised the weapon and as one inspired took aim in the moonlight and sent a bullet through the head of one of the mules. He reared on his haunches, and with marvelous rapidity L discharged all the chambers into the two animals. The first hit died in- stantly, but the other poor brute was only wounded, and in her frengy she overturned the wagon, throwing us on a soft sandbank. I was a little dazed by the fall, but that soon passed off, and I examined the operator’s wound. He was shot in the shoulder and was bleeding profusely. Con- sciousness had returned, and I fixed him as comfcrtably as I could, which, poor fellow, was anything but comfort. The excitement of the night had worn me out, and the operator was weak from loss of blood. My timepiece told a quarter of four. Our train left at six. How far was it from San Anselmo, I wondered. We could not have been more than seven miles from San Ramon when the attack was made, and surely we must now be very near the border town. And who knew what wild tale the greaser would tell at San Ramon? The operator was young and of slen- der build. My one chence lay in risking the distance and catching the train. Once over the border we were safe. With but little hope in my heart, I lifted him. He felt as heavy as a thousand pounds, and the pain in raising him sent him into unconsciousnessagain. It took me fully two hours to walk that haif mile to town, but—we caught the train. TO REVIVE THE LOST MYSTERIES OF ANTIQUITY B"52 O MOST people the fact thata college of “occult science’” =) is to be founded in the United States would be an evi- dence of a reversion to the dark ages, when black magic was supposed to flourish, but the society which is about to erect this institution claims that it is a revival of the light and civilization of ancient times, says the Phila- delphia Times. That such an academy is to rise within 2 our borders, that America, which is the youngest coun- try of modern times, is to be the sacred center in which: are to.be taught the mysteries of Osiris and Isisand of the Greek, is the latest announce- ment from the inner school of fheosophists, and one which it bas only _ decided to make public within & very short time. A few weeks ago there set out from America for a tour around the world a small band of theosophists, headed by Mr. Hargrove, the presi- dent, and accompanied by Mrs. Tingley, who bolds the position of corre- sponding secretary, which was once the post occupied by Mme. Blavat- sky, and which is one of the most important in-the society. These mis- sionaries are called the crusaders, and they propose o go into every land, planting the seed of their doctrine in every nation. This doctrine, which they claim is to be the future belief of the American people, is not a mod- ern seet, but a faith which was born in prehistoric times, lived in its glory during the civilization of ancient Egypt and Greece, and was practiced even on the continent of America, when it was the Atlantis which existed before the dawn of history. They assert that these doctrines have de- scended by master minds or adepts, and have thus been preserved, espe- cially in Thibet and Indis, where the learned occultists live. Over $36,000 has been already subscribed toward the erection of the “School for the Revival of the Lost Mysteries of Antiquity,” but the site has not yet been announced for the reason that the holders of the desired land would raise their prices if they were aware of the wish of the society to purchase the property. It is supposed that the building ‘will be begun next spring, and that within its walls those who wish to belong to the Inner Scbool will be here instructed free of chdrge in the wonders of occultism, which the adepts possess.