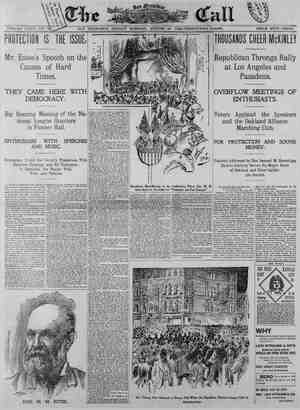

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, August 30, 1896, Page 23

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, AUGUST 30, 1896. 23 BEGINNING TO WIN ITS LONG OVERDUE FAME Sidney Lanier has been scarcely more than a vague name to the great messof American readers. It is fifteen years since his life went out under the pines of Nor¢h Carolina and it is only now that the recognition of his right to rank with our great American voets is becom- ing general. His recently published letters, edited by William Thayer, have created & wider interest in the man and his work. Mr. Thayer says: I know not where to look for & series of letters which in bulk equally small retate so humanely and beauti- fully the story of so vbrecious a life.” While Lanier lived there were few with the insight to discern his worth. Since his death each year has brought a wider recognition. In 1890 the English Spectator said of him: “Lanfer died 0 early that he did not really show us more than the bud of his genius, but 1f he had lived ten years louger he would, we believe, have ranked high among English poets and probably sbove every American poet of the past.” This was high praise from a great English journal, nine years after the death of the man, whose_appreciators while he lived might al- most have been counted on the fingers of one hand. In tnese daysof fads and sudden fame for “work of little value, it seemed a cruel thing that the man whose work has survived so well the relentless test of time should have the bitterness of unappreciation added to hislife struggle. Life was indeed a struggle from first to last for Sidney Lanier. He fought poverty and ill health with splendid courage, and never wavered in hisfaith in hisown ultimaie success. He wasone of those rare souls who w-Tite because they must—impelled from with- in by they know not what hidden force. He speaks in one of his letters of being “racked in every fiber by the birth of & new poem.” He followed his muse up a steep and thorny path which led him to the heights—never to the fleshpots of Egypt. Lanier was born in Macon, Georgia, in 1842. He was the first of those brilliant writers which the South has given us in recent years. His family—who dated from colonial days in the South—were of French Hugueaot descent. Like Pierre Loti, he had that impressionable and artistic blood in his veins—with what a different result in these two men! The living French writer and man of the world has for- tune and fame and sociai distinction, yet finds himself forever unsatisfied with these and sad- | dened by the hopelessness of unfaith; while our dead Southern poet struggled against ail the ills of life, yet left the memory of an une quenched hope and courage of spirit. At the age of 14 Lanier entered Oglethorpe College, from which he was graduated with honors. When the war broke out he enlisted in the Georgia Volunteers. Point Lookout, where he hardships. After being exchanged he made his way on foot to Macon. On reaching home he broke down with the first premonitions of his ter- rible enemy, consumption, which fifteen years later ended his life. He recovered from the first attack, secured a clerkship and married & Miss Day of Macon. She became a most de- voted wife, sustaining him always by her ten- der care and her faith in his genius. Lanier's father wished him to practice law. He tried it for a time, bui found it hopelessly uncon- genial. From this time his career wassadly checkered. He taught school for a time, played first flute in the Peabody orchestra in Baltimore, drifted from one thing to another with constant breaks in his work because of ill bealth. Mr, Thayer says ‘‘neither sickness nor drudgery conld long turn him from the deepest craving of his spirit.”” In 1875 his long poem **Corn” was published in Lippincott’s Magazine. Lippincott’s, though not ranking first among American journals, hak the unique distinction of being in many instances the first to recognize the worth of work by unknown authors. Mr. Peabody, edi- tor of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, to whom most of the recently published letters were aadressed, wrote a glowing review of ““Corn” in the columns of his paper. It was almost the only recognition the poem had, and Lanier was correspondingly grateful. He wrote Mr. Peabody s warm letter of thanks, which led to a correspondence and later an in- timate friendship. After this time Lanier made shift to keep the wolf from the door by his magazine verses, a miserably uncertain dependence. Probably only a poet can know the misery of having to write at the demands of an empty pocket. In 1876 he had become so far known thnat he had the honor of being chosen to write the words for the opening cantata of the Cen- tennial. He was rarely gifted in music as s poetry, and it was his great desire to show the scientific connection between these two branches of art. Some yearslater he de- livered a course of lectures on the ‘‘Science of English Verse,” in which he sought to prove that the law of rhythm in sound applied equally to words and to music. He was terribly handicapped at this time by successive attacks of his malady. One winter be had 10 drop everything and go with his wife to Florida—their two boys being left with the good friends, the Peabodies. The letters from Tampa to Philadelphia that winter are of the most intimate character. They record his gradual recovery in the balmy air of the South and hisreliefatbeing able tosend a check (just received from some magazine) in part pavment of a long standing doctor’s bitl. In the spring they returned to the North, and next year there seemed to be some small respite to those money worries. He writes from Baltimore that they have taken and are furnishing a little house, which causes them great delight and a feeling of importance at being absolute housenolders. After this he gave lectures in addition to his literary work. A little later there was some idea, much favored by President Gilman, of establishing a chair of music and poetry at Johns Hopkins University and presenting it to Sidney Lanier. This plan was the foundation on which Lanier built many dearly cherished hopes, but it was never fulfilled. He was, however, engaged to deliver several courses of lectures at the uni- versity. It was there that he gave his course on “The Science of English Verse.” The sec- ond course, given just before his death, con- tain the lectures published under the title of “The English Novel.” There is much even of contemporary criticism that is still valuablein these essays. Lanier’sbent was always toward what is sane and wholesome in art. It is, however, in his poems of nature that Lanier is at his best. His “Hymns to the Marshes” breathe an ecstacy of sppreciation that must thrill every lover of nature who reads them. The greatest of these is‘‘Sun- rise,” the last poem he ever wrote, and the one by which his name will be remembered wherever English poetry is known. Iknow ot no other poem which so suggests the flavor of the early dswn, its freshness and exhilara- tion. But no; it is made. List! Somewhere—mystery, where? In the leaves? in the air? Inmy hear.? is a motion made. *Tis 3 motion of dawn, like a flicker of shade on shade, In the leaves ’tis palpable; low multitudinous stirring Up winds through the woods; the little ones softly conferring Have settled my birds to be looked for, s0; they are sulll; But the air and my hesrt and the earth are athrill, And. look where the wiid duck sails round the bend of the river, And look where a passionate shiver Expectant is bending the blades Of the marshgrass in serial Shimmers and shades, And invisible wings fast fleeting, fast fleeting, are beating The dark overhead as my heart beats and steady and free I8 the ebb tide flowing from marsh to sea. The poem ends with a splendid pean of strong and feariess in the face of like the writer's own soul: endured many prai despair, After two years’ | service he was taken prisoner and confined at | I must pass from the face, I must pass from the face of the sun, 0ld Want isawake and agog, every wrinkle afrown, The worker must pass to his work in the terrible town, 4 But I fear not, nay, I fear not the thing to be done, I am strong with the strength of my lord, the Sun! How dark, how dark soever the race thatmust needs be run! 1am lit with the sun. Oh, never the mast-high run of the seas Of traffic shall hide thee; Never the hell-colored smoke of the factories hide thee: Never the reek of the times fen politicshide thee, And ever my heart through the night shall with knowledge abide thee, And ever by day shall my spirit as one that hath tried thee Labor at leisure, in art, till yonder beside thee My soul shall float, friena Sun, The day being doae. Fitting last words for a man whose whole life was a triumph of the inner light over outward darkness. GRACE 8. MUSSER. A NEW LIFE OF CHRIST. Many have been the attempts ot writers and painters in the past to present an accurate idea of the figure of Christ and the personages of bis time. More especially has it been the favorite theme with literary men. In this connection we have had the splendid works of Archdeacon Farrar and Ernest Renau, whose ideas ran rather in the direction of essayists. | tures were surrounded by admirng crowds, | General Lew Wallace and Marie Corelli, again, tried to treat the same subject, using a serip- turel background, but with a leavening of fiction, For the painters there are the works of Rubens, of Rembrandt and of numerous others. But it must be confessed that the works of all these have been the means of creating in the public mind a vast aggrega- tion of what, for want of a better term, can be called false 1mages or impressions. It has been left for a painter of to-day, M. James J. Tissot of Paris, to give to the worid a truthful representation of the life and times of Christ— to disengage it, us far as possible, from a mass of conventional legendary lore, at once in- accurate and misleading. M. Tissot’s work had a curious origin. He returned in March, 1887, from a visit to Je- rusalem, with a fow sketches that he had made in the Holy Land. These he showed to his father, a pious Catholic. The parent, regard- ing the ‘work of the son, remerked that the sketches banishea many cherishea illusions derived from a study of the Bible and a con- templation of some of the works of the old masters. Tissot the younger then conceived the idea of returning to Paiéstine and of mak- | ing, from actual topographicaland other ob- servations, a series of paintings illustrative of the life of Christ. Eight years were to be de- voted to this gigantic work. The results of his journey, or some of them, were exhibited in the Salon of 1894. The en- thusiasm and interest they aroused was won- derful, even for Paris. Day after day the pic- and it was quickly recognized that here, at | last, was & man who had reproduced with lifelike accuracy the external setting of the events recorded in the gospels. The advance sheets of Tissot's “Life of Christ,” just issued, bear witness to the pains taken by the artist in the matter of accuracy. Scene siter scene is presented with what would seem almost the power of & seer. Here we see the ornate temples and houses of the Herods and the simpler and more harmonious lines of older buildings; there a wonderful study of the Pharisee and the publican. Some of these pictures are very small, yet the appli- cation of & powerful glass only serves to reveal in them new beauties. The painter has been greatly assisted in his work by the fact that he is himself a scholar, besides being a devout Catholie. For these reasons he has had access to rare books, prints, carvings and tapestries hidden away in monasteries and other places inaccessible to the ordinary tourist. M. Tissot has made careful studies in the Talmud and in the writings of Josepbus. In connection with his work he has also made a new translation of the Latin text of the Vulgate. The Latin and French texts are pre- sented side by side, and the pictures are fully explained in the notes which accompany 4hem. Appended is a technical description of the book, translated from the original French: “The work will be composed of two volumes of about 600 pages each, illustrated with 865 aquarelles by Tissot, and about 150 explica- tory sketches—character-heads, costumes and landscapes, after nature—friezes, ornamental letters and tail-pieces, designed by the artist. “0f the 365 aquarelles, which are repro- duced in color by the newest processes, giving absolute fac-similes of the originals, 329 are interspersed with the textand 36 outside the same, of which latter 16 are drawn on copper- plate and reproduced in tint. “The text is printed in Elzevir ty pe, specially cast, with explanatory designs engraved on wood. “Each volume will be numbered and will bear the name of the subscriber.” As we haye shown the work is & monumental one. This being the case it would not be reasonable to expect that it would be within the reach of every one’s purchase. The first twenty copies on specially made Japan paper are listed at 5000_francs each, or, roughly, $1000. These have all been bought up by wealthy bibliophiles. The remaining copies of the edition, to tLe number of 980, will be sup- plied at 1500 francs or $300. The cost of pre- paring the work, therefore, could hardly have been less than a quarter of a million of dollars. THE CALL is indebted to Mr. William Doxey for a view oi the advance sheets of Tissot’s work. M. A. G. Drandar has finished a circumstan- tial account of the political history of Bulgaria from 1876 down to the present time. Twp volumes edi from the notes of lec- tures of G. C. Robertson, late Grote professor in University College, London, are in prepara- tion for Murray’s University Extension Series. One is entitled “Element of Philosophy,” the other “Elements of Psychology.” “THE SOJOURN IN EGYPT.” [From a painting by James J. Tissot, as reproduced in “Tissot’s Life of Christ.”} ORGOTTEN VERSE CULLED FROM A SCRAPBOOK MORE THAN THIRTY YEARS OLD HOW LONG WILL IT LAST? Lights from the windows are gleaming nd | glancing, Music and laughter are echoing near, S8ave where the twain move apart from the dancing Uttering vows'each was longing (o hear. Tender his tones, in their low modulation, Timidly downward her glances are cast; Eyes matched with sapphire, cheeks carnation, Fair is the picture—how long will it last? Think when old Time, of all jokers the grim- mest, Whitens the tresses and furrows the brow, Changing the forms that are lithest and slimmest— Will your affections be steady as now? True that to-day, in its ardent devotion, Love takes no heed of the future or past; Curbing and checking the tide of emotion, Prudence it last with All were in vain, though the caution be needed, Prudence is ne’er the companion of Passion for aye leaves unnoticed, unheeded, Warnings of wisdom and promptings of truth, Forging the fetters that bind them together, Gilding the hours that are fiying so fast; Careless of sunlight or stormiest weather, Love never questions, ‘‘How long will it last?” L E. L WOUNDER AND HEARLER. Translation of an Arabic song. Thy witching look islike a two-edged swora To pierce his heart by whom thou art sur. veyed; Thy rosy lips the precious balm afford To heal the wouna thy keen-edged sword has made. Iam its victim; I have felt the steel: My heart now rankles with the smarting pain; Give me thy lips the bitter wound to heal— Thy lips to kiss and I am whole again. —Chambers’ Journal. FATE. Two shall be born the whole wide world apart, And speak in different tongues, and have no thought Each of the other’s being, and no heed. And these o'er unknown seas to unknown lands 8hall cross, escaping wreck, detying death; And, all uneonsciously, shape every act And bend each wandering sten to this one end— That one day out of darkness they shall meet And read life’s meaning in each other’s eyes, And two shall walk some narrow way of life, uld whisper, “How long will | outh; | 1 | So nearly side by side that should one turn Ever so little space to left or right Theyjnr‘eds must stand acknowledged face to ace. - Ana yet, with wistful eyes that never meet, With groping hands that never clasp, and lips Calling in vain to ears that never heer, They seek each other all their weary days And die unsatisfied. And this is Fate. ACROSS THE SUNLIT LAND Come, love, across the sunlit land As blithe as dryad dancing free, While time slips by like silver sand Within the gless of ‘memory. Ere winter, in his reckless glee, Blights all the bloom with ruthless hand, Come, love, across the sunlit land, As blithe as dryad dancing free! And all the years of life shall be Like peaceful vales that wide expand Tomeet a bright untroubled sea By radiant azure arches spanned; Come, love, across the sunlit land, As blithe as dryad dancing free! CLINTON SCOLLARD. GROWING OLD. Is it parting with the roundness Of the smoothly rounded cheek? Is it losing from the dimples Half the flashing joy they speak? Is it fading of the luster From the wavy golden hair? Is it finding on the forenead Graven lines of thought and care? Is it dropping—as the roseleaves Drop their sweetness, overblown— Household names that once were dearer, More familiar than our own? Is it meeting on the pathway Faces strange andglances cold. While the soul, with moan and shiver, Whispers sadly, “Growing old” ? On the gradual sloping pathway, As the passing years decline, Gleams a golden lovelight, falling Far from upper heights divine; And the shadows from that brightnes Wrap them soitly in their fold, Who unto celestial whiteness Walk, by way of “growing old.” E. L. THE PARADOX OF TIME. Time goes, yousay? Ah no! Alas, Time ssys, we g0; Or else, were this not so, What need to chain the hours, For youth were always ours? Lead through some landscape low; We pass, and think we see The earth’s fixed surface flee— Alas, Time stays—we go! Once in the days of old, Your locks were curling gold, And mine had shamed the crow. Now in the selfsame stage, We've reached the silver nge; Time goes, you say?—ah no! Once when my voice was strong, T filled the wooas with song, To praise your “rose’” and “snow”; _My bird, that sang, is dead; Where are your roses fled? Alas, Time says—we go! See in what traversed ways, ‘What backward fate delays The hopes we used to know; Where are our old desires?— Ah, where those vanished fires? Time goes, you say?—ah no! How far, how far, O Sweet, The grass behina our feet Lies in the even-glow! Now, on the forward way, Let us fold hands, and pray! Alas, Time stays—we go! AUSTIN DOBSON. EPISCOPO AND COMPANY. By Gabriele d’An- punzio. Translated from the Italian by Myrta Leonora Jones. Chicago: Herbert S. Stone & Co., publishers; for sale by Doxey: price $1 25. Gabriele d’Annunzio is not well knowxn by his works or even by name to the public of this country; but he haswon recognition in the literary circles of Europe, especially in France. Jules Lemaitre hascalled him “the romantic poet of the Italian renaissance.” He is not yet 33 years old, and is already ranked asoneof the great Italian writers of the pres- enttime. A volume of verses which D’An- nunzio published in 1883 were so extremely erotic as to bring upon him the same censure that fell upon Swinburne when the latter's “Poems and Ballads” first appeared in Eng- land. D’Annunzio has genius, but that genius is largely stained by moral defecis. “Episcopo and Company” is one of his lesser and earlier works, and it is to be regretted that the trans- lator should not have chosen one of the Italian author’s later and worthier novels through which to introduce him to American readers. In the book at hand he treats of lowest life in Rome after the manner of the realists. The deathbed story of Giovanni Episcopo is unfit for the earsof young readers. Some of the passages border closely on the obscene. The style is exceedingly nervous, reminding one much of Poe’s “Tell-Tale Heart.” Take, for example, this: Did—did you see—the corpse? Did it not seem o you that there was something extraordinary in the face, in the eyes? Ah, 1 forget, the eyes were closed—not both of them, however, not both. I know that well. I mustdie1f ouly to rid my fin- gers of the feeling of that eyelld which resisted. Ifeelit here always,as If & bit of the skin had stuck on the spot. Look at my hand. Is it not a hand that has already begun to die? Look atit. Episcopo is a bloodless being —a coward, wholly under the evil influence of a bad char- acter named Wanzer. He bows to this man’s slightest command or wish. Episcopo marries, but Wanzer made the match. The latter leaves Ttaly for & few years. Meantime, Episcopo be- comes the father of a boy, whom he names Ciro. Then suddenly Wanzer returns and seeks to force Episcopo again iato slavery, He succeeds for a time. He wins the smiles of Giovanni’s false wife, and then one day he beats her, and Ciro attacks the brutal Wanzer. The woman flees. Wanzer departs for & short time, but returns, and it is now that the base slave frees himself, because of his love for Ciro. Wanzer looks about for the woma and during this time Episcopo stands petrified; he cannot move. Let the story as it closes tell itself here: “Suddenly my child uttered & cry, which in- stantly freed my rigid members. My eyes turned toa long kmfe which shone on the sideboard and my band clutched it. Prodigious strength filled my arm. 1 felt myself carried as on a wave tothe door of my son’s room, and I saw my son clinging with feline fury to Wanzer's great body, and I saw Wanzer'’s hands upon my son. “Two, three, four times I plunged the knife into his spine up to the hilt. “Ab, sir, for chariiy’s sake do not leave me alone! Before night falls Iwill die. I promise youTI will die. Then you may go; you will close my eyes and go away. But no, I will not even ask that. Imyself before I die will close my own eyes. “Look at my hand. It has tonched the eyelids of that man and it has turned yellow. Those eye- 1ids, 1 wanted to close them because Ciro kept sit- ting up in bed and crying, ‘Papa! papal he is 100k- ing at me? “How conld he have looked at him, covered as he was? Can the dead look throngh eheets? “The leit eyelid resisted, cold, cold— “How much blood! Ts it possible that a man contains & sea of blood? The veins hardly show: they are so delicate you can hardly distinguish them. And yet—there was no place left where [ could put my foot; my shoes were soaked like two sponges—strange, was it not?—like two sponges. - - * * * * - “One of them, so much blood; and the other not adrop—alily. O God, alily. Isthereanything so white on earth? «Lilies, only lilies! «But, 10ook; 100k, sir! What is bappening to me? What is 1t I feel «Before night falls; oh! before night—" We anticipate with pleasure the translation into English of d’Annunzio’s latest and best novel, “Vergine delie Rocce.” It is claimed for it that it will withstand two tests of really great literature; namely, “that something shall surviye the first reading of the book, and that it shall be impossible to read it only once.” -LITERARY NOTES. It is hoped that the first and second vol- umes of Gibbon’s unpublished works will be ready this autumn. John Strange Winter has finished & rew story which will be published shortly. The title of it is not announced yet. Henry Hardwicke, & member of the New York bar, has written a history of “Oratory and Orators,” which &e will publish soon. Anatole France, the French academicfan, has written & preface to along poem by M. Leon Heley. The pcem, entitled ‘“Mentis,” is to ap- pear very shortly. The Hon. James Bryce’s “Impressions of South Africa” will soon be published in book form. Four of these articles appeared in the Century. Mr. Bryce’s knowledge of the sub- \ \ Time goes, you say? Ah no! Ours is the eyes’ deceit Of men whose fiying feet “NOW THE MUSE OF BELLES-LETTRES IS WEEPING.” [Drawn for “Tha Call” by a staff artist.] N ITALIAN PROSE WITH A VIVIDNESS LIKE EDGAR ALLAN POE 1 ject, his statesmanship and his qualifications as a writer will make this a standard work. Miss Edgeworth’s well-known story “Helen” 1s to be included in Messrs. Macmillan’s Stand- ard Novels. Itwill have an introduction by Mrs. Ritchie, Thackeray’s daughter, and illus- trations by Miss Chris Hammond. A 'new edition of the late Mrs. Lamb’s ““His- tory of New York” has been prepared for Messrs. A. S. Barnes & Co. by Mrs. Burton Har- rison, who has added a chapter on the ex- ternals of the modern city, with illustrations. This chapter will be published separately, also, in the same style as the whole work. “Rhymes of the States,” by Garrett New- kirk, with Harry Fenn's illustrations, will be issued by t he Century Company in October. It is a geographical aid to young people, con- taining brief facts of the importance regarding the aifferent States of the Union and novel illustrations, which will help boys.and girls to remember the salient features of each State. Joel Chandler Harris has revived his “Daddy Jake, the Runaway,” which was issued several s ago, and a new edition in attractive form will be published by the Century Company in the autumn. It contains a number of stories of Brer B'ar, Brer Terrapin, Brer Fox and ! other famous animals, told to the well-known little bov who . is the recipient of theold negro's confidences. It was formerly issued as a square book,but is now reset and made 8 companion to Kipling’s jungle books. Austin Dobson has prepared another series— the third—of his “Eighteenth Century Vige nettes,” The contents of the new volume arg of & vefy varied character and will include; “Exit Roscius,” “Dr, Mead's Library,”” Grog loy’s **Londres,” “Polly Honeycombe,” “Thomas Gent, Printer”; “The Adventures of Five Days,” “Fielding’s Library,” “Came bridge, the Everything”; “The Officina Ar. buteana,” “Matthew Prior,” etc. The work will be published in London by Messrs. Chatto & Windus, but will” not appear for some little time. One of the most interesting of forthcoming volumes will be the work desling with the Brontes, on which C. K. Shorter has now been for some time engaged. He has had the advan. tage not merely of severalinterviews with, but is also receiving from, Mr. Nicholls, Charlotte Bronte’s still surviving husband, & number of MSS. which the latter had always hitherto de« clined to partivith. - Mr. Shorter differs froun Mrs. Gaskell and some other Bronte students in their judgment with rélation to Branwell, regarding -whose ‘life story snd that of the gifted sistecs of Haworth parsonage there will be much that is both new and interesting in the volume, which will appear in the autumn, Brentano’s oi New York announce for early | publication ¢‘Short-Suit Whist,” by Val W, Starnes. The short-suit game contemplates the endowment of the intermediate cards of all suits, trumps included, with winning props erties, by taking advantage of their position in tenace, by underplay, and by strengthening leads which shall be judicjously finessed by the partner. It also prefers making one’s own and partner’s trumps separately on the master cards of the enemy, when the opportunity oc« curs, instead of having them fall together. | This is the pioneer volume in its especial field, | for since the advent of *“Cavendish” and Pole, all writers on whist, with the exception of | Foster, have advocated the long-suit game to | the exclusion of all other forms of whist | strategy. [Frem a painting by James J. Tissot, as '“ JESUS WORKINC WITH JOSEPH.” reproduced in “Tisso's Life of Christ.””] THE PROMISE OF THE AGES (a poem). Charles Augustus Keeler. In a blank-verse poem of fifty pages Mr. Keeler has attempted to present the struggles of an earnest mind with some of the modern life-problems; and, in the personality of the Prophet, to exhibit these questions as they pass through the mind of the idealist. As to the basis upon which the poet proceeds, he re- marks in his introduction that “The law of evolution forms the keynote of this latter nineteenth century. It is the principle of transformation, of growth, of progress. Ithas profoundly modified our thought in all fields of observation and speculation, reconstructing the foundations of science and challenging the dogmas of religion. In striking contrast to this modern conception of-the origin of the forms of existence is the more venerable doc- trine of a divine creation, executed con- sciously by the volition of God in order that his love might find expression in tangible form. The clash of these two opinions, with | their innumerable side-issues, is termed the | conflict of science and religion. If religion is to prevail in this conflict, it will be at the price of certain concessions popularly deemed of intrinsic importance, and especially by the surrender of all which cannot be defended by reason, namely: the miraculous.” Mr. Keeler observes that the frank use of the subject-matter of science in poetry may be called into question, but he believes that a justification for this is found in the recogni- tion of love the snimating principle be- neath all the conflict and tumult of the ages. ‘The poem recognizes the principle of evolu- tion, but seeks to transcend this with the higher thought of the ultimate reality of the spirit. It is an attempt at a synthesis of the essential ideas of Darwin and Emerson. The poem is dedicated to Berkeley’s eminent phil- osopher, Joseph Le Conte, in the following lines: Seeker, whose science o’ermasters the spirit's despair— Teacher, whose truth mounts to heaven in worship | and prayer— | Prophet, whose deeds are a witness of faith, free and strong— Not to tender vain tribute to thee, do I pledge thee my song. ‘But to gain from thy life and thylove, benediction, dear friend, To hallow my labor with graces thy presence can lend. Mr. Keeler's wide fame as a scientist and author, and his rank asa poetof more than ordinary merit, will commend this small | voluwe to the distinguished considerstion of an extensive circle of readers. He sings of the immortality of the soul and his verses contain many passages of beauty. The impressive last words of the dying prophet near the close of the poem breathe a powerful sermon in them- selves: Map’s love is the heart’s love—man’s work and his lore By ROMISE OF THE & AGES—SOME BLANK VERSE DEDICATED TO JOSEPH LE CONTE Is the spirit’s assertion of freedom and life; | Man’s hope is the heart’s nope—man's faith and his trust Is the spirit’s bellef in the beauty of truth; Man’s truth is the soul’s truth—the soul’s truth iy whole trutb, And th e whole truth is God with his lovingof man, Man’s love is the Lord’s love—man’s work and his lore Is the Lord’s mighty planning revealed in hig son Man's hope is the Lord’s hope—man’s faith and his trust | 18 the faith of the Lord in the beauty of truth; Man’s truth s the Lord’s truth, that smites the heart’s chords’ truth, And the heart’s chords are ringing with God's love for man. THE MODERN READER’S BIBLE. Genesis— Ecclesiasticns. New York: The Macmillan Company. Forsale by Willlam Doxey; price 50 cents each. These two little books are part of a series, The Modern Reader’s Bible is an attempt, and a very successiul one, to place the revised version of the Testament in such a form that the historical, oratorical, statistical and epic portions shall be easy of access to the general reader. To read the Bible is, of course, a simple mate ter; but to read it with appreciation is made somewhat difficult by intricacies of style, and, as the editor notes in his préface to the Book of Genesis, by the differences in the form in which books are presented in ancientand in modern literature. Professor Moulton, under whose scholarly supervisioa this series of aids to the stndy of the Scriptures has been issue bappily describes the manner in which the avecage reader of the Bible is handicapped, by saying that while books presented in such shape will be read, they will not be read with zest. *‘The constant necessity of mentally allowing for differenee of literary form makes such reading resemble the use of a microscope with an imperfectly adjusted focus; by thinking it is possible to make out what the biurred picture should be, but the observer’s attention wearies, and all the while | a turn or two of & wheel would give clear vision.”” To this we can add that Professor Moulton has given the necessary turn of a wheel. Be siaes the undoubted scholarly character of the work, there is that in it which betokens a 1abor oi love, undertaken in'a reverent spirit, Than this nothing more need be said to indie cate its value, both to students and to the general reader. According to the eightieth annual report of the American Bible Society, its total issues, at home and abroad, for the year ending March 31 last, amounted to 1,750,283 copies. The issues of the society during the eighty years of its existence amount to 61,705,841 copies, — . Every msp should read the advertisementfof ‘Thomas Slater on page 21 of this paper.