Omaha Daily Bee Newspaper, October 25, 1903, Page 30

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

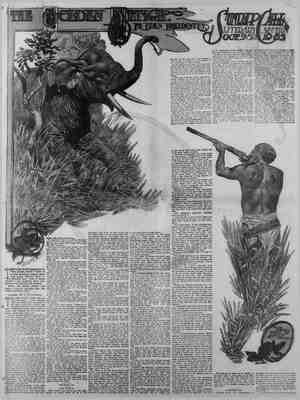

The opyright, 193, by J. W. Muller) CHAPTER XXI1V N the Sea-Alp — Late I drive the workmen, diive, drive. Despite the double pay that I give them they grumble We have no slaves any more, but tn thelr place are socialists and anarchists. It is necessary that some great ruler shall become a little like Nero again. I begin again to make the night my day., Whe light of the sun s too yellow, tos conrse, too common. It ¢hinea on too much misery that shricks constantly toward the Reaven. Can you not hear how It peals from the depths? 1 hear it con tantly. . . . - . . . . I wonder does my noble adjutant report my doingn to the Royal Court Marshal oe perhaps direct to the King? Probably. Aund what does he repart? That I intend to be King some day deapite that signature under the sgecret document that they cheated me into signing. I will tell the nation that. Por I shall speak to the nation, the whole nation'! The whole nation would arise for me and fog my rights; it would bell;ve in m>, would love me again. But the King still lives. Yesterday 1 climbed the path that leads to the White Emperor Meadow, and withe out my adjutant. It was wid autumn weather, Scarcely had I began my climb Before mists arose, thick as the smoke of a vast conflagration. The clouds blllowed around me like the storm-scourged waves of & phantom sea. I had to giop* wi h my feet, with ray hands, on one side the naked steep wall and on the other the sheer abysa, And the path was 80 narrow. 1 could not turn, I would not stand still, I had to go forward. And the storm tore &t me and tried to pull me down. But I withstood. Buddenly a howling blast tore the misls apart. And close in front of me I saw the rock over the chasm where my father had clung through a night of storm. My father bad withstood the King's test. Now I, that was his true son, would withstand it, too. And if I withstood it, then— Following the Godllke thought I had the rock In my embrace the next moment, let the storm seize me and hurl me from the path, hung between heaven and esrth, hung over the abyss, while it grew darker and darker, while the black night crept in through the raging tempest. If my arms remained strong, if 1 did not let go of the rock, if I withstood the King'a test, It would be a celestial sign that the erown hung over my head and would sink en my brow. Time passed and I began to count the minutes—one—two-three—it lasted an cter- mily before I had counted sixty. But my arms must remain strong. 1 closed my oyes and time passed. | felt mysellf weakening, and 1 had to remain strong. My limbs quivered as in o fit, my arms became lame, my hands tried 1o pen. But my will was mightier than my human weakness, and 1 held both hands locked around the rock. Then it was as if I had running streams of fire in my veins instead of blood. They poured into my brain and burned it up, They sprang out of my feet that dangled over the chasm. They poured out of my eyes that 1 could not open any more. And time passed. Then came a frightful moment. 1 felt that my strength, my will, had reached the end, and that I, not the true son of my tather, would crash into the depths. In the same moment, just as my hands were loosening—my closed eyes were daz- zled by a blinding glare—the rising sun! 1 had hung all night over the abyss, be- tween heaven and earth; my mighty will bad given me power to do something super- buman, to withstand the King's test. The crown of my brother hangs over my head and will settle on my brow. 1 will make my land great, my nation happy. I swung myself over the edge and back to the path. Then my sense passed. My adjutant found me and carried me— all alone—in his arms to the house. I dreamed in my swoon that I heard voices. And one voice said that the Prince had lost his way and barely saved himself from falling into the abyss by seizing a rock, from which terrible position he had been saved within a few moments by his adju- tant, who had followed him secretly. Within a few moments! What strange dreams one has. . - . . . . . . autumn. Much is being whispered in the newspa- pers about His Majesty the King. There are hints of great nervousness with grow- ing insomnia. That is bad. Lately an issuc was confiscated because it spoke of the King's weariness Since a King may not be weary, such an utterance is like high treason. Many papers are keplt away from me, (oo I know why. Because they mention my name again and again. That, also, is high treason. I hear that legends are being told about my life in this Alpine wilderness That is good. A monarch must be a logendary figure for his people. I can un- dorstand the Caesars who upraised them- selves to gods. What was the result? Teu- ples were bulit in thelr honor, columns were erected, even the Roman Senate showed them the honors due to immortals, and (he Weary Kings | TIME PASSED, AND I I FORE I HAD COUNTED BIXTY. nations of the earth crawled before them. Only g0 can the will of a ruler become the highest law, God's own law. Since I spent the night hanging over the abyss I feel myself lifted to sunny heights, CHAPTER XXV, On the Sea-Alp. The beginning of winter, The workers have gone and a part of the new edifice is ready and furnished. Every- thing is still only improvised, so to speak, and petty and unworthy of me. But one can see what is to be. Tomorrow I awalt Judica. We dwell in a suite of six rooms. Between our sleeping apartments—we sleep apart because of my loud dreams—lle our toilet rooms and the tath. It is a high domed room, in which a blue twilight reigns. The basin is rosy marble. The water flows out of the tilted jar of a nymph and a white bed of flowers borders the pool. Blooming shrubs—none but white flowers—hide the walls, In my future Grail Burg there shall be a whole pond instead of the poor little pool: Lotus shall grow on it, lilles and papyrus shall border it, behind them shall arise palms, A waterfall shall roar into it and I will make the stars rise and revolve as I wish, . . . . . . . . I must watch myself ever more closely; must dissemble ever more. There must be no single human being who knows anything about me. Then, at last, I will have the desert golitude, that churchyard peace, that inaccessibility that is due me. Even you, my only trusted one in the whole world, you poor, pale paper, shall learn less and less from me. You might become a traitor and betray to the world how cruelly I suffer sometimes. But that cannot be told in words. . . . - » . . . Since yesterday it has been snowing. My forester—the same one who obeyed the royal whim of his King—has organized the boat service over the lake beautifully and has appointed an army of the strongest and bravest of the men to keep th> path clear along the shore in case the ice should close the water. This path will be the only entrance to the world. I can open the gate or close it at will—a rapturous know!ledge. The household employes may not show themselves before me except when abso- lutely necessary. My adjutant hardly ap- pears. Yet I feel myself watched, spied on, followed constantly; I know that he is for- ever sending reports about me and so must forever be on my guard. No doubt some wise authority on psychol= iGAN TO COUNT THE MIN ogy is In the house even now in some dis- guise; the lackeys are, without doubt, only disguised nurses and keepers. I have ex- perience in this matter. It snows, snows, snows! No soul dreams of the wonders I see nightly; for nightly I leave the house. All day they must make paths for me and none may meet me, Like a monster amphi- theater of white marble the mighty circle of snowy mountains stands around me. Over them is spread a dark blue velvet cur- tain embroidered with gold. Around the ice-crowned head of the White Emperor shines moonlight like the aureole around the head of a Saint. The flood of light pours downward. The white walls shine, the white earth gleams. My Grail Burg stands complete, It would be wonderful to have plays here in this tremendous hall under the full moon. There should be mystery plays, parades of beautiful young beings in cere- monial garments, dances and processions accompanied with prayers and psalms. And I would be the only spectator, the ruler of a fabled world. What would I not perform! What world would I not stamp out of the ground! Give me the power! CAPTER XXVI. On the Sea-Alp. March. I intended never to write again. never. The paper is so clean and white before I use it. It is as if my words spotted some- thing pure and bright. And now, after all, I sit here again over this book that cone- tains part of myself and in which I write down how my mind commits mortal sins. War is possihle. That sounds llke a feverish phantasy. My own feverish brain might have such mad hallucinations. But the thing is not in my sick brain. It is in the newspapers; the possibility of war with our young, strong and daring northerm neighbor. it would be a fight of anmihflation between a degenerate, senile state and a youthful power that fairly bristles with strength, vitality and ambitions. The young, strong stranger wil tukc my inheritance, my realm. For my brother's realm is mine since the night when I with- stood the test. If I placed myself at the head of the army, I that am Inviolate and anointed of God, the strength of my strength would go into the army, into the whole nation, and we would conguer, A single victory would save us, for a gingle victory would give us the belief A Modern Romance By Richard Voss UTES—-ONE-TWO—-THREE—IT LASTED AN ETERNITY BB in ourselves again that we lost so long ago. Was there ever in my life a time when I found war horrible, a crime, a murdep of all Godlike attributes in man? W there ever a time when I wished in ma@ moments that the realm of my father® might be dissolved In that of a strongeg and greater race? What madness, what weakness, whas cowardice! War! War! . - . . . . L) . As soon as war is declared I will go inte the campaign even if I have to fight as a private. My spirit would be the leader still, leading the troops, filling them, take ing them on to victory. My brother, the King, is weak. Witk every breath he is unkingly. In the papers I see that the people and the governmeng have little hope for a peaceful solution— that they do not even wish one, because nation and government desire the war. But the King will hesitate and vacillate, shrink and remain weak. And in the nature of the case we are the ones who must declare war. The declarae tion is expected of us. We will cover our- selves with everlasting shame if wec hold back. The King will give his consent with his heart’s blood—if he gives it at all. I imagine they will have to force it from him. . . . . . . . . The conflict is getting more and more tangled and a peaceable solution is grow- ing ever more improbable. Ever more pas- sicnately the government, the nation, presses for the arbitrament of sword and bloed. The fear, the ETOWS. His wife's State would ally itself with us; the dynasty that is to rule after us would join us. We would be three against one, But that one will conquer us three, for he is mightier than we together. There would be only the chance that the miracle for which I walt shall appear. I shall not wait in vain. And what shall be done then with Judical She must not stand in my way! - . . . . . . < Bouth wind and thaw! The lake thaws, too. The water is im- passable now and there remains only the path along shore. And that is open only 80 long as it can be kept clear of snow and avalanches. The south wind howls like a throng of loosed demons. From all sides pour the deluges of freed streams, and avalanches indecision of the King ey ——" )