Omaha Daily Bee Newspaper, October 25, 1903, Page 23

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

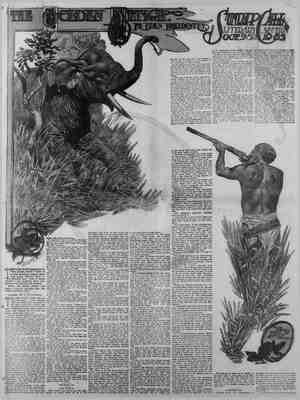

The Cannibal Dandies of the Yari (Copyright, 1903, by Thomas 8 N AUGUST 2, 192, I left Call, the principal town in the de- partment of the Cauqa, Republic of Colombia, on an expedition into the interior of the country. I was accompanied by another white man— an English doctor—and four natives. Our Alexander)) object was to collect entomological speci mens in a section of Colombia hitherto un- explorcd. We did not return to Cali until June of the present year. In the interval we had many stirring adventures and extraor- dinary experiences among savage (tribes, but the one episode of the trip which over- shadowed all the others in romance, inter. est and excitement was our six weeks' stay among the cannibal dandies of the Yari river. They are surely one of the strangest Bavage races ever discovered. over weeks and months of travel and adventure, let us start with one morning when, on the banks of the Rio Hacha, our native peons deserted us. They would go no farther, because we were ap- proaching the dominions of a succession of savage tribes who hate the Colombians, and pruactice cannibalism. Fortunately, we struck the camp of a white Colombian who was gathering rubber on the banks of the river. We had been recommended to him by Senor Pedro Pesaro, a great man in the Colombian rub- ber business, and he, therefore, gave us, for guides, two Indians who had come in from one of the neighboring tribes to sell him rubber. One of these men spoke Spanish, and so we could use him as an interpreter. Besides our guns, revolvers and provi- ®ions we carrfed in our canoe a large stock of machetes, looking glasses, scissors, pen- knives, fish-hooks, brightly-colored cloths, and other articles calculated to purchase the good-will and assistance of the savage tribes through whose territory we had to pass We rowed down the Rio Hacha for four days, until we arrived off the settlement of the Tama Indians. There we landed, leaving the guns and everything else be- hind in the canoe. Our guides led us along a narrow track, through dense tropical vegetation, to a clearing where the tribe dwelt together in one great house, as is the custom of all the Indians in this part of Colombia. The tribe only numbered from forty to sixty people, the rest having been killed off shorily before by smallpox. Perhaps this misfortune had soured the temper of the tribe, for they certainly gave us a very cold and forbidding reception. Our two Indians walked before us, carrying paddles over their shoulders—a sign of peace—and ex- plained that we were friends. The chief of the tribe was lying on the ground, evidently suffering agony. He had a bad ulcer on the calf of his leg, and had not been able to move or sleep for a week. The doctor offered to cure him, and, after some demur, he consented to an operation. We sent back to the boat for a lance t, and the doctor opened the leg, made an incieion down the calf, took out a big thorn and dressed the wound. ‘While he was doing this Skipping several of the Tamas grouped themselves around our party, handling their blowpipes, wcoden swords and hatchets significantly, and plainly intimating that they would kiil us if anything went wrong with the chief. Luckily, he slept that night for the first time in a week, and the next morning noth- ing was too good for us. We stayed three days with the tribe, until the chief was quite recovered. During that time they found out from our Spanish- speaking Indian what we wanted to do and where we wanted to go. As soon as the chief was convinced that we were not there for gold or land, or to enslave and murder the Indians after the-Colombian fashion, but only to look for butterflies and such like things, he was eager to help us, He gave us two picked men to act as our “‘bogas,” or guides, and take us to the next tribe. Our own Indians went back. The etiquette of these tril'es directs that men of one tribe must not ps through the terri- tory of another tribe to a third. Travelers arce passed along by different guides from each tribe—unless thev are killed by the first savage Indians they meet. Our “bogasr” conducted us to the Orte- quasas, a tribe numbering about 400. Hear- ing a flattering account of us, they natu- rally received us well, and promised to pass us along with all due honor. The Tamas then returned to their tribe, Now came one of the remarkable experiences of our trip. The Ortequasas sent a message introducing us to the next tribe, and they s=ent it by wireless teleg- raphy. This Is the only name I can apply to their method, The transmitter was a felled tree trunk about twenty feet long and one and one-half feet in diameter. Down the center of it a groove was cut about three inches wide by six inches deep. One end of the trunk flouted in the river and the other end lay on a sandbank. The operator had a heavy stick about three feet long, on the end of which was a ball of crude rubber weighing about twenty-five pounds. He got this by the simple expedient of cutting the bark of the rubber tree and twisting the sap round the stick as it flowed out, most He struck the end of the trunk several times with this heavy ball. It did not make much noise—indeed, hardly any-—but a very powerful concussion or vibration of the air could be felt. It was just like the sensation of being in a tunnel when a shot is fired. You felt the sound rather than heard it, And the next tribe, several leagues farther down the river, could feel it equally well, and could read off the message 1 tele- graphist receives the dots and dashes of the Morse code over the wire, Evidently these savages had a code of their own by which they could telegraph any message th wished. All the tribes in this region were constantly communica- ting with onv another by this wirecless sys- tem. Next day we saw a man of the tribe to whom weo had thus been introduced sending back a message to the Ortequasas by a similar apparatus. Every tribe we passed after that sent an introduction ahead in this way, besides giving us two “bogas.” Travelers among savage tribes in South America, as weil as in other parts of the world, have often been puzzled by the repidity and accuracy with which these barbarian Marconis transmit news to one another. Here is one explanation, at ail events, No doubt there are others. At last we got to the Yaris, who are named after the river on which they dwell, which Is a tributary of the River Caqueta. At 7:30 o'clock one morning, while we were having breakfast, we heard strains of weird, barbaric music, which evidently came from rative reed flutes. We pushed off our canoe from the bank and paddled out on a river twice as broad as the Hud- son at New York. Around the next bend we met a number of canoes filled with scores of painted In- dians. They paddled alongside, gave us a warm welcome, and wer very eager to help us with the canoe. Never had we been received more cordially, Our two “bogas’ from the last tribe, of course, went back; and the Yaris took us up a tributary of the river to their home, The tribe numbers between 2,000 and 3,000, and all the members of it live in one enor- mous house. This house is more than 300 feet long and over forty feet wide at the base, sloping upwards in a triangular form. The walls are made of thin fern sticks and leaves, delicate’y and beautifully woven to- gether, and very solid. It is a wonderful piece of workmanship. Iuside the house is supported by a great number of posts, between which hammocks are slung for the men of the tribe to sleep ifn. On the floor, squares of bamboo, on which the women sleep with thelr children. Kach family has its own cooking fire and domestic utensils, and lives its own family life in this vast house, surrounded by all the other families. We were conducted into this hquse, and the Indians crowded around us—men, women and children—all overflowing with hospitality and curiogity., The first sight that met our eyes in the house was a long line of skulls suspended on the walls, There were skulls of monkeys, pigs, fishes, jaguars, and many other animals—and also, among the lot, there were eighteen which were unmistakably the skulls of human be- ings. It was evident, too, that they were skulls of civilized men, for some of them had gold fillings in the teeth, It would be absurd to say that this sight did not make us feel queecr, but we were not frightened as might be imagined, be- cause we had heard the story of those eighteen men from the other tribes along the river. They were eighteen Colombians who had fled from civilization to escape being pressed into the government army to fight the revolutionists. Four months hefore our arrival, they settled among the Yarl In- dians. Being well armed with guns and revolvers, they cowed the tribe for a while and started to collect rubber. They were men of the lowest and most brutal char- acter, and before long they began to flog and shoot some of the Indians, One afternoon a baby cried in the big housge and annoyed the leader of the gang. He coolly drew his revolver and blew its head off. The Indians, who were sitting around, busy at their various occupations, did not say a word, They showed no trace of emotion; even the baby's mother suppressed her grief. But that night they arose from their sleep and slew the eigh- teen Colombians, Next morning, by they invited the “barracoucha’—a a ‘‘barracoucha’ wireless telegraph, neighboring tribes to a feast of white men. At all tribal feuds are sunk, and the chiefs sit {ogether in an enormous hammock which holds as many as forty men. They do not eat human flesh for food; they have plenty of that of all kinds. Nor do they eat it they like it, The motive is religious, or, rather, super- stitious. They believe they wiil acquire the qualities—courage, strength, endurance, cunning, skill—of the enemy who forms the dish. The Yaris and all the other tribes we visited hate South American white men, for they have suffered much at thelr hands; and they Ekill and eat them whenever they get a chance. But they readiiy under- stood that we were a different kind of white men. They are always ready to because behave well toward Americans, ki h- men, Germans and others whose motives and deeds are good. There was never any suggestion of making a “barrac ucha” of us, As soon as we got inside the big house, the chief inquired by signs whether we would eat, and led us to his fire, which was the largest In the house, His wife, who particularly attentive, no doubt under his orders, gave us two clay bowls and filled them from a stcwpot simmering on the fire. She used for a ladle a dried, shrivelled human hand. The bony fingers were close together, and curved like the talons of an eagle. The sight tock away my appetite, and made me wonder what might be in the pot But the portion served to us consisted mainiy of p feet, 80 we concluded it was all right, The kindly, generous hospitality with which we were received was continued during the whole of our six weeks stay among the tribe. Apart from their un- pleasant habit of eating their enemies, the Yaris are a fine race of savages, who can give points in morals and manners to many civilized men. There was much in them to admire. The men had only one wife aplece, and were always most kind and faithful to her. Marriage was by consent of the woman-—a thing rare among savages. Adultery was hardly ever heard of; if it happencd it was punished by the sure divorce of dealh. The guilty man and woman were each put, alene, on one of the thounsand little islets in the river, to starve to death or be slain by wild beasts. It was plain, even to us, who could not speak their language, that the husbands and wives were deeply atttached to one another and fond of their children. Family In\u' was often charmingly displayed and the men took great pains te teach the youngsters how to hunt and fish and to train them in the myriad points of wood- craft invaluable to an Indian. They were honest folk, and men of their word. The Yaris and all the ncigh- boring tribes never fail to carry out an en- gagement if they can possibly do 0. They had it in their power to rob us of all our possessions, which, be it remembered, con- sisted of articles they coveted intensely. But they stole nothing. One day we went down the river, about five hours' journey, to another small tribe, an offshoot of the Yaris, which comprised only about twenty-four people. An Indian there fell violently in love with a big knife I carried and intimated by signs that his earthly happiness would be complete if he could only have the knife. He would do anything for it. I signed to him that we wanted a big fish and then gave him the knife. Among these people it is always the custom to pay in advance. We returned to the Yari house, expecting to see the fish; but about midnight we were awakened by the playing of a flute on the river. It was our friend coming up with an erormous fish which he had captured for us The business methods employed by the rubber collectors are a striking testimony to the honesty of these tribes. The white merchant goes to the big house of the tribe and throws down his stock of barter on the floor. ¥ach Indian takes what he desires—one a looking glass, another a ma- chete, a third a pair of scissors, and so too, forth. The merchant then departs to his station, having disposed of his stock in trade and received mnothing for it He does not even know what each individual Indian has taken, indeed, he does not know one Indian from another. But he can rely on their good faith, Three months or six months afterwards, according to the eenson, the Indians begin to arrive at his station, bringing rubber to Hay for the goods they took. They tell him what they had, and he weighs the rubber and usually has to give them some- thing extra, according to the =scale of barter, Sometimes a few Indians will not arrive, but the chief of the tribe says, “So-and-so was killed while hunting. Here iz the machete he took,” or “So-and-so was sick and could not gather any rubber, Here is his looking glass.” The most extraordinary thing about the Yaris is their dandyism. They are the greatest dudes under the sun. No men on earth think more of their personal ap- pearance, or devote more time to it Yet the result is by no means entrancing. The men are absolutely hideous in face, with pronounced, protruding teeth. Their complexion is a bilious copper color. In stature they are stunted, but they are well formed, lithe, agile, and hold them- selves very erect. Their expression, which is ferocious, belies their nature. They cut their hair short at the neck and straight on their foreheads. 'Through the cartilage of the nose they put a stick about an inch long and a quarter of an Inch thick, which raises the nostrils. They put a similar stick through each ear. They paint their faces and bodies in gaudy eolors with vegetable dyes, and It is in this they show their dandyism most forcibly, When they are not working or hunting, they spend all their time painting themselves and ar- ranging thelr hair, On one canoe voyage we had with us two old “bogas,” who were the greatest dandies of this primping people Every fifteen or twenty minutes they would stop the canoe, jump out and wash themselves thoroughly Then they would renew theie paint and go ahead. When they arrived at the end of the day's journey, tired and hungry instead of hurrying to light a fire, cook dinner and make themselves come- fortable for the night, they would first spend an hour painting themselves and dolng up their hair The Yaris paint the foot, up to the ealf of the leg, with some red vegetable dye which protects them from insecct bites On this foundation they create a fine decorative scheme in blue and black. The body and face are also paioted. Of all our trade goods, what pleased the Yaris most was an article never intended for them We took with us some blue Ink in tablet form, intending to melt it to write our diaries with One of the In- dians took up a tablet, dipped it in water and drew some lines on his body with it, He was overjoyed when he found that these lines did not wash off readily, like his own vegetable dyes After that these tablets were our most valuable coin. The women of the tribe have very delicate noses and fine hair Like the men, they aro most cleanly in thelr persons and their habit and attentive to their toilet They g0 nuked, but modest and virtuous, Through their upper lip they thrust two thorns, each being an inen and a half to tv o inches long. They do not adorn them- ure selves s0 much as the men, or waste so much time in dandyism. DBoth men and women have remarkably small feet and hunds The chief wears a necklace of tiger's teeth, to indicate his rank, and also three gaily colored feathers in a coronet made of the plumage of birds Unlike most savage chiefs, he is not a fat lazy, dissipated brute. He s the clev t awd hardest working man in the tribe His children wear necklaces of monkey's tecth, and his chief assistants, or also wear a few monkey's teeth During six months of the river is high, the the big house, and men and women do the rivers fall bodyguard, the year, entire tribe lives in during that time the not cohabit. When and leave great sandbanks exposed, each family builds a little hut of sticks and leaves on one of the sand- banks, and the husband and wife then live together. As a natural consequence, nearly all the children of the tribe are born about the same time. A childless woman is regarded as a very unfortunate person, She is dosed with a mixture made chiefly of the scraped claws of the glant arma- when dillo, which is supposed to remedy her misfortiine, Perfect cleanliness and order prevail in the bLig house. One day we were smoking cigars there, and carelessly dropped some ash on the floor. Immediately one of the women came along and carefully swept ugy every particle into a palm leaf. The tribd has good ideas of sanitation, and, In con; sequence, their health ie always excellend In the evening the house is lighted by of procured from turtle's eggs. During our stay the Yaris behaved splen didly. They could not do enough for us, We could only communicate by slgns, bu' they showed great intelligence in compre- hending our wishes When they under stood that we wanted butterflijes they wenp out into the jungle and brought us baskety fuls, but, unfortunately, all were crusheq and useless. Our “bogas” on the return journey were A man and his wife and child. The family love they displayed was pretty and touch- ing. On our way back to Call we were ate tacked by about forty Indians, who had evidently not heard of our friendship with the tribes. They fired scores of poisened arrows at us from their blowpipes, but for- tunately they were on the bank and our canoe was in midstream. Some of the are rows stuck in the canoe, but we were not hl‘. We paddled out of danger without re- turning thelr fire. Call was safely reached last June, after many exciting adventures, and from that place T came up to New York. The doctor went to England, where he is now making preparations for another journey into the unexplored interior of Central South America. THOMAS 8. ALEXANDER. Poor Richard J unior Formerly it Muke good! was, Be good! Now it 1s, Some of the dollars of the daddies now g0 to the caddies, There are no fashionable sections along the road to success, He who hesitates is— well, he is apt to get the better of the bargain, This 18 the season when the debutante comes out by going Into soclety, Water in the trusts does not include the weeping of those who bought the stocks. With a miliion children outside the schools there does not seem to be enough prosper= ity to go around. John Bull's new idea of economics is te ask his children to send their savings home. Of course, John Bull s home.—Saturday Evening Post