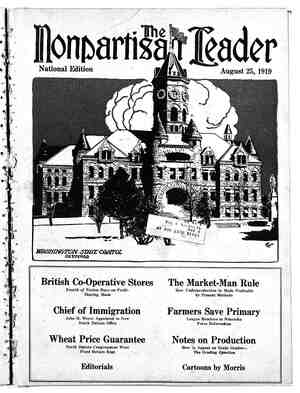

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, August 25, 1919, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

i B _ effect on production: Market-Man Rule Boosts Living Costs Profits Through Price Manipulation Hold Down Production—Most of Loss Profits No One—League Farmers’ Program Offers Way Out | BY A. B. GILBERT NE of America’s greatest efficiency engineers, H. L. Gantt, pointed out during the war that our great difficulty in " pro- ducing goods lay in the policy, “business as usual.” Our whole busi- ness system is cast in the mold of profit-hunting through marketing rather than in that of profits through greater and more efficient production. “If profits were based on produc- tion,” says this engineer, “and not upon competition in selling, there would then be only one way to in- crease profits. - That would be through increasing production. Maximum pro- duction of wealth, or 100 per cent ef- ficiency, would become the goal of all industry.” In common with many other engineers, Mr. Gantt holds that our factories are only about 25 per cent They are owned and run by men whose specialty is the markets and who wouldn’t know how to be efficient in production even if they had the efficient. desire to be. It is natural that an honest, observing engineer should have such opinions because, like the farmer the actual producers in factory and in mine are under the do- minion of the market fanipu- lators. And right here is the great trouble with American busi- ness today — market-man rule instead of producer rule. The profiteers, of ‘course, are dangerous. They aggra- vate the evil. But the major part of the evil—the failure to produce goods in adequate quantity—profits no one. A great army of men who would be employed in adequate pro- duction of factory and mine are unemployed and being witheut income they can not buy as they would from the farmers. Thus the farmer falls into the vicious circle and farm production in turn is held down. : : Let us look at some cases of vicious market rule and its ’ Early in 1917 the war brought a great demand for coal, iron, copper and oil. In- stead of trying to see how much of these products they could turn out, the market men immediatély began to see for how much they could capitalize the scarcity. They secured their great profits from higher prices for the same quantity rather than through adding to quantity. Some industries forced strikes, manipulated the railroads and turned other tricks so as to win more in the market. PROFITEERING FAILED TO PRODUCE Pig iron production in the first 10 months of 1917 was . 542,625 tons under the produc- tion for the same period in 1916. With prices soaring to double and treble the prices of the previous year the coal companies in 1917 got out only the usual amount of coal. Cop- per production ran under that. of the previous year, for the copper interests kept many of their men and mines idle for months. Readers will ‘recall ‘the great strikes in the Butte. ° (Mont.) and Arizona fields “‘\\\\s /',\- X < \\\\\\ ‘\\\-\‘ NN R\~ .\ NS N \\ NN ,,,fl\'_\ WL \\\\\\\ \ ST i profits on necessities. This article digs deep into the problem of the high cost of liv- |. ing. It is not so much an expose of the profiteers as of the - cause of profiteering—*“business as usual.”” The market ex- perts or manipulators, with their hosts of salesmen and adver- tisers, have dominion over our production of necessaries. Through business evolution it has come to pass that they seek and obtain their profits, not through greater production but by forcing up prices. They get greater and greater profits from the same or a smaller quantity of goods. American mines and factories are in-the hands of captains of idleness rather than captains of industry. Farm production is forced below cost. The system must be reversed if we'are to have relief. The government, as advocated by the Nonpartisan league, must take possession of the marketing. It must so regulate mines, forests and factories that their owners can get profits only by becoming 100 per cent busy. which the big press asecribed to labor disloyalty. In other words, the profiteering allowed did not produce for us. It merely stimulated hope - of still greater profits through market hold-ups. This is “business as usual” and this is what has been going on during the war here and since. Little wonder that prices are high! The Standard Oil furnishes a view of the problem from another angle. W. C. Van Antwerp, one of | GETTING AT THE ROOT OF IT | ez < N\ oM \ %M; I; —Drawn expressly for the Leader by W. C. Morris. The high cost of living has brought to the attention of congress, after a long time, the wide- spread profiteering. As a result there has been much discussion-of means of curbing excess The organized farmer and worker, however, in their program have pointed the way to cutting down the high cost of necessities through government- operation of packing: plants, railroads and other public utilities of the kind. ' PAGE FIVE / ; T A S B B T R e R B T T A e S 30 T IO T by B P D Bt the leaders in the Wall street stock exchange, brings out in a series of articles on oil companies running in the Wall Street Journal, that only 17 per cent of Standard Oil property is in the crude oil production end of the business. He declares also that a company can hardly succeed in the oil ' business unless' it follows the product through to the consumer as the Standard does. What does this mean except that this trust has such hold on the market that it artificially keeps down the production of crude oil ? It breaks the crude oil market by establishing a supposed market price for crude oil below what independents can put it on the market for, and the ' trust takes back more than it is sup- posed to lose thus in the processing and selling of the finished products. While it was thus cutting down funda- mental production, the Standard Oil company of New Jersey (the big parent company), in the seven years ending with 1918, averaged 55.49 per cent on its common stock a year. This figure is taken from its own statements. The steel trust illustrates opposite tactics for the same purpose. deposits in northern Minnesota and much else- where. At the Cleveland and Pittsburg markets it It owns over 80 per cent of ore _establishes a fictitiously high price based on what independ- ent mines would have to pay for the railroad, docking and shipping service which it owns. This high price of ore handi- caps all producers of iron and steel in competition with the trust. The steel trust strategy, thus keeps dowr: production of independent mines and indes pendent blast furnaces. Wasig mere oversight that led the government officials to let the price of iron ore run wild in 1917 and 1918, when prices were named for iron and steel ? It would take more than denial to show that it was not col- lusion with the trust. FARM PRODUCTION HELD DOWN Readers of the Leader are familiar with how the packers likewise keep up the cost of marketing livestock through overcharging independents for services on which they reap the profits. {The very fact that the independents are able to stay in business at all shows the in- efficiency in packing trust mar- keting. The market men in general who deal in farm products keep - down farm production because they go after the highest prices obtainable for what they sell. This cuts down consumption in a frightful manner. They in turn buy less from the farmer - and at much lower prices. Farmers then find it doesn’t pay to try to produce more. They have to cut on fertilizer, on labor, on borrowing for larger operations. ‘While. the packing trust has been forcing down the price of livestock to the extent of over 25 per cent since April 1, re- tail meats have shown com- paratively little decline; in- creasing in some instances, and leather has climbed upwards. Between April 1 and July 25 the wholesale price of hemlock sole No. 1 was boosted from 46 cents to 58 cents, and union cow backs from 70 to 94 cents. Why? Because our market (Continued on page 14)