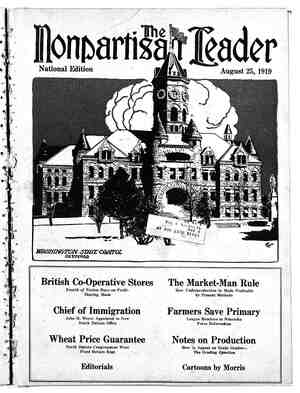

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, August 25, 1919, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

k] 4 British Retail Co-Operative Stores £ st pasenca e e A i T i ( Purchasers Share in Profits of Shops—Fourth of Population of Britain Buys Through Societies—Wide Variety of Goods Sold The writer of this series of articles, after serving in France with the American. Expeditionary Forces, was transferred to ‘Trinity college, Cambridge, Eng., and while stationed there took opportunity to investigate, for the Nonpartisan Leader, the political and economic movements of the British Isles. On a previous trip to Europe, as a member of the Ford peace party, Lieutenant Fussell visited Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Holland and a part of Germany. As a _member of the American Expeditionary Forces .he has visited France, Italy, England, Ireland and Scot- land, so he is well qualified to write on European conditions. BY LIEUTENANT PAUL FUSSELL WISE man once said that one-half of the world does not know how the other half lives. Every American school boy knows something of the way Great Britain is governed. He knows that there is a king and a prime minister and houses of parliament, and that the British navy is the largest in the world. But there are many adults in America who have never heard of the co-operative movement in Britain, though the amount of money handled each year by the co-operative societies is far larger than the peace-time budget set by the house of commons. : In three articles I shall sketch the outlines of the British co-operative system, dealing in this article with retail co-operative stores; in the second with wholesale co-operation, and in the third with agki- cultural co-operation. England is the land where the industrial revolu- tion came overnight. At sunset, the farmer’s wife was ‘weaving cloth, baking bread and cooking the food her husband had raised. At dawn, the same woman found herself in a smoky city, buying mill- made cloth, bread from the bakery, and produce from the grocer. The man became a factory hand, and banded him- self with others into a trades union. The woman became a purchaser, and banded herself with others into a co-operative society. The trades union protected the husband as a laborer, securing him shorter hours and better pay. The co-opera- tive society protected the wife ‘as a purchaser, securing her larger measures and lower prices. SOCIETIES NOW SELL AT CURRENT MARKET PRICES In the years when the co-operative movement was young—roughly, from 1795 to 1833—the socie- ties sold for the lowest possible sum, without desire for profits. By 1833 there were 400 co-operative societies, and. annual conferences of representatives were held. In that year the conference recommend- ed that the co-operative stores should sell at the same prices as other stores, retaining the profits for the extension of their business. The real beginning of the present plan, however, came from the Rochdale Socie- ty of Equitable Pioneers in 1844. By their plan goods are sold at current market prices and at the end of each six- month period the profits are divided. Some go to the purchasers in proportion to the amount of their- purchase; some to the society for the ex- tension of the business. This plan, which is known all over the world as the ‘“Rochdale system,” spread rapidly and is used today in all co-operative enterprises. Just how does a co-opera- tive store work? Let us sup- pose that you should move to- morrow- to the city of Cam- bridge, Eng., where it happens that I have been living for the last three months. You will find it a city of 50,000 inhabit- ants; and the home of one of the world’s oldest universities. One of your first questions would: be, - “Where shall I shop?” Then your friendly Britain. of agricultural co-operation. fundamental reforins. ‘tered through the town so neighbor would tell you of the Cambridge Co-Oper- ative society and take you to their central office on Burleigh street. There you would pay a shilling (a “quarter” at home) and become a member of the society, with a membership book and a number. There are already 8,403 members in Cambridge, so that you would be No. 8,404. Perhaps the clerk who enrolls you would teil you that the central store sells groceries, dry goods, shoes, millinery, furniture, meat, coal, bakestuffs and confectionery, and that there are 17 branches scat- that the society is convenient to every one. i Being now a member and entitled to make purchases at the central store or any branch, - you step down the street and give a large order: A good supply of staple groceries, a roast for Sun- day, a pair of shoes for the boy, a hat for yourself, a ton of coal, and some chairs for the dining room. Now all these articles are sold at standard market prices, and you may be wondering how you -benefit by the co-opera- tive system. : But as you pay your bill (“cash only” is the co-operative motto), the clerk inquires your number. “Eight thousand four hundred and four,” you reply. And so the purchase is credited on the books of the store tq 8,404, and you are given a paper check bearing that num- ber and.the amount of your purchase. The end of a six-months’ period approaches. The dividend is declared by the directors, generally a shilling and 6 pence on the pound, or, as we axl Lieut. Paul Fussell Central Store of the Belfast Co-Operative Society, Belfast, Iréland, one of © . tive societies in Great Britain. This is the first of a series of articles prepared for the Non- partisan Leader on economic and political conditions in Great The British workmen and farmers have brought about, by their own efforts, remarkable improvements in their conditions in recent years, especially since the great war. Lieutenant Fussell, who has had opportunity to get first-hand information of this people’s movement, describes in this article the start of the co-operative movement nearly a century ago. In later articles he will tell how this movement spread, first to wholesaling and manufacturing and then in the direction But the farmers and working- men of Great Britain have found that while co-operation solved many of their problems, it was not enough by itself. They found it necessary to go into politics to obtain substantial and Later articles by Lieutenant Fussell will deal with the birth and growth of the English Labor party and the movement for industrial democracy—a movement that is now in full swing in the United States. should .say, 7 per cent. If you had purchased $200 worth of goods during the half year, you would be credited with $15 on the society’s books. This credit — all a clear saving through trading with the co-operative stores—you can withdraw if you wish, or leave with the society. If 'you leave it, the society will pay you 5 per cent interest, compounding semi- annually. In fact, you may, if you wish, deposit other money with the society and have it draw interest, for the co-operative is more than a store for its members—it is a bank as well. As a member, you are entitled not only to dividends in proportion to purchases, but also to attend the quarterly’ meetings. Here you will help to decide the general conduct of the business and elect nine directors for the coming three months. These directors appoint the manager and secretary and hold weekly meetings to follow the conduct of the society. They decide how large a dividend is to be paid, when new branches shall be opened, and how surplus profits shall be invested. SMALL STORE HAS $1,000,000 SALES Conducting the co-operative society in even so small a city as Cambridge is no simple task. To begin with, there are more than 200 employes to be selected. It has always been a part of the co- operative policy to give the employes an eight-hour day, instead of the 10 or 12-hour day that prevails in most retail stores. Last year the total sales amounted to more than $1,000,000, and the dividends to more than $75,000—all a clear saving to the members. 3 Figures showing the magnitude of the co-opera- tive stores throughout the British Isles since 1917 are not available. But in that year there were 3,788,490 inembers, or about 6 per cent of the popu- "lation. While any person over 18 may become a member, there is generally only one member to a e e e S T R SR T 00 fgmily. If an average family be assumed to con- S}St of only four persons, it is apparent that prac- tically one-fourth of the population buys through ‘the co-operative stores. Altogether, sales of retail stores amounted in 1917 to £142,008,612, or, in American money, about $700,000,000. A wide variety of goods are sold. Of 1,267 co- operative societies reporting in 1916, 1,264 had groceries, 1,180 dry goods departments, 1,166 shoes, 1,082 hardware, 870 furniture, 749 coal, 614 meat, 556 tailoring, 380 millinery, 100 bakeries, and 83 restaurants. Six even conducted their own under- taking departments, and so took-care of their mem- bers to the very grave. Many of the societies find it profitable to produce part of the goods which they sell. All of the larger societies operate their own bakeries, tailoring, dress- .making and millinery branches, and repair boots and shoes. In general, however, production is left to the Wholesale Co-Oper- ative society, an organization which we shall discuss next week. These co-operative societies, scattered .through 1,400 cities and towns in the British Isles, are open to any one who wishes .to join them, but most of the members, like the farseeing man who foupded them more than a century ago, are the laboring people of Britain. They thrive best in the great industrial centers where they originated. They are, indeed, an institution “of the people, by the people and for the peo- . ple.” - > ) (A second ‘article on the ’ workings of the co-operative system in wholesaling will ap- pear in next week’s issue of the Leader.) . the 1,400 co-opera-