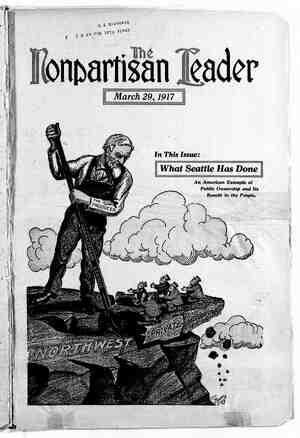

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, March 29, 1917, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

v “Spuds” and the Cost of Living Fewer Potatoes for More Money or More Potatoes for Less Money? The Farmer Has a Problem as Well as the Consumer HAT is the cause of the pres- ent high price of potatoes? It is not as easy to discover as some people in the cities, who imagine the farmers are making all the profits, imagine. Nor do the tales of potatoes being dumped into rivers to hold up the price explain it for potatoes have been too costly all season, and are too scarce throughout North America, to make this wanton method of raising prices necessary. There are many theories as to the cause of the high prices, but they differ 80 widely that none of them can be taken at full face value. Here, how- ever, are a few facts that show the difficulties of the prcblem. The United States is somewhere be- tween 75,000,000 and 100,000,000 bushels short-of its normal supply. Europe is getting no American grown potatoes, and war competition does not apply. The United States is already import- ing from Canada the first consignments of what will become as large a ship- ment as Canada can spare. = The United States for mearly 30 yvears has been importing in round numbers three times as many bushels of potatoes as it has been exporting, mostly from Canada, but sometimes from' Ireland. Last year the great northern potato states were drowned out. In the South there was also a shortage, but the South does not cut much figure, coming in principally for the May and June product, while the North supplies the bulk of the demand, and all that goes into storage for win- ter. The yield of potatoes in the United States in 1915 (1916 figures are not yet available) was 359,103,000, in 1914 it was 405,921,000 This year potato prices are higher than they have ever been, and people are organizing boy- cotts against them, hotels are serving them less lavishly, and families are using them sparingly. PRICES OUT OF REACH OF ORDINARY _POCKETS Prices are everywhere enormously out of reach of the ordinary pocket book. For instance the first week in March, Minnesota grown potatoes were quoted in Minneapolis in car lots at $2.55 to $2.75 per bushel. Kansas City was quoting similar kinds at $3 to $3.10; and Chicago was quoting Minne- sota and Wisconsin potatoes at $2.50 to $2.65 per bushel. People begin to refuse to eat potatoes at this price and think of them as luxuries. In New York, the pent-up city population formed into food mobs, and poured kerosene on potatoes and other vege- tables, overturned peddlers’ carts, and destroyed a considerable quantity of this costly food, blaming the small re- tailers for the high prices. The big newspapers carried comic stories of the sudden jewelry price of potatoes. For instance, a farmer bought matinee seats at a fashionable theater with a handful; a tippler bought a cocktail, gave a potato in pay- ment, and got back a nickle in change; an East Side huxter struck his fellow man with his fist and was fined a bushel of potatoes instead of the cus- tomary $b. Back of this confusion, tragedy and levity, back of the enormous quantity of potatoes that the United States’ 8,700,000 acres of potato fields produce, there must be something out of joint. Buyers for great distributing houses of the Twin Cities and Kansas City, A crew gathering the potato harvest in the Red River valley. These are Early Ohios, the choice crop of the Red River section, and the finest eating potato grown. The Red River valley crop is used largely for seed in Kansas, Oklahoma, lowa, Nebraska and other nearby states. : Potatoes so high that a poor man can hardly afford to eat them—annual production far short of annual needs—yet farmers don’t think it worth while to hold enough for seed. Why? Because the market is all in a mess with unregulated competition and excessive profits to speculators. It’s the same old story—the urgent need of market regulation, of state or government control of marketing facilities. now in the Red River valley, declare that no one has a corner on potatoes. One of the largest dealers in this staple testified in Chicago before a fed- eral investigating body a week or two ago that he had 1,000,000 bushels of potatoes in storage, but buyers in the Red River valley scout this idea. If he had, and there were several others like him, that would hardly make possible a corner in potatoes, which would sprout and spoil before the boycotters would succumb. Every farmer knows potatoes are perishable, and can not be hoarded like grain. Potatoes to bring profits must be sold to consumers early in the season. The South is already growing 'its 1917 crop, which will begin to come on the market in May, and potatoes of the 1916 crop will soon be- gin to dwindle in commercial impor- tance. No, with a new crop growing, and the people determined to stop eat- ing potatoes, the temporary hoarding of a small per cent of the crop does not account for the potato panic. THE FARMERS GET: LESS FOR BIGGER CROPS But out of this confusion snatch this fact and examine it awhile: in 1914 when the United States produced 405,- 921,000 bushels of potatoes, the farm value as shown by government figures was only $198,609,000; while in 1913 when the country produced only 331,- 525,000, the farm value rose to $227,- 903,000. In other words 405 million bushels brought the growers $29,000,000 less money than 331 million bushels. The farmers had the labor and expense of producing 74,396,000 more bushels of potatoes in 1914 than in 1913, and yet they got $29,294,000 less for that extra labor and expense. Farmers remember things like that. They need not study government re- ports to learn it. They know it by sweat, and backache, and burning sun. They know the year they got next to - nothing for their toil, and threw in the use of their good land free. They know the years they get a fair price, or a big price. The average farm price per bushel for potatoes in the whole United States in 1913, the year of a light crop, was 68 cents per bushel, while in 1914, the good year, it was 48 cents (barring fractions of a cent). In 1912 with more than 420,000,000 bushels produced, the average farm price was 50 cents; while the year before that Interior of a typical potato warehouse in the Red River valley. This particular building at Hawley, Minn,, is one of the latest and most approved con- struction and belongs to Leslie Welter, of Moorhead, one of the largest shippers in the valley. The sacks, sorter, and crew may be seen in the background. This building is 110 feet long by 30 feet wide and has a capicity of 35,000 bushels. outer wall is of solid brick, next comes a wall of hollow brick, then a three-inch air space, and a third inner wall of hollow brick, which insures absolute protec- tion from frost. EIGHT o Its with only 292,000,000 bushels it was 79 cents. In 1915 it was 61 cents. Farme ers can not forget such facts as those. They are thinking about them intense- ly right now. The gospel of making two blades grow where one grew be- fore, loses its appeal, when all this brain power and muscle power, and hard cash, that go into making that extra blade grow, brings in a smaller return than the one-blade effort. RED RIVER VALLEY TO BE SHORT OF SEED ‘With this in mind Red River valley farmers are selling themselves short of seed this spring. Potato handlers of the valley, and buyers for the big cities say there is not enough seed to plant even last year’s reduced acreage. Dr. Boyle of the extension department of the North Dakota Agricultural college agrees with them, and says he does not believe there is enough left in farmers’ hands to plant more than half of last Year's acreage. Figures on file at the North Dakota Agricultural college show that the cost of producing a bushel of potatoes inm. 1914 was 16 cents per bushel, in 1915, 35 cents per bushel; and for three years in Clay county, Minnesota, in the heart of the Red River potato section, $32 an acre. This year with prices what they are now, it would cost about $30 “an acre just for the seed in the Red River section, using about 12 bushels at a price of $2.25 or a little more per bushel. Farmers would rather take their $2.25 per bushel now, and save work and . expense, than put $30 worth of potatoes into the ground and take chances on having to sell the 90 or 100 bushels it might produce next fall at 50 cents a bushel. To plant potatoes at such a price for seed, would require _ the abandon of a hardened speculator. They won’t do it. PLANT FEWER POTATOES INSTEAD OF MORE This means in simple, hard facts, that the Red River valley will plant fewer potatoes, and that the crop from this section will be even smaller this year than last. For the same reason, (namely because Red River valley Early Ohio potatoes are so high), the farmers of the great Kaw valley sec- tion of Kansas and Oklahoma who re= plant their potato fields annually from Red River valley cuttings, are refus= ing to buy Red River seed. They be= lieve the seed at present prices would cost them more than they would get from the harvest and they too refuse to work for nothing. And, because economic conditions tend to equalize and counter balance each other, as~ water seeks a common level, the farm- ers in Wisconsin, eastern Minnesota and Michigan will likewise refuse to speculate in their own labor, and the fickleness of a season. i Thus the famous Early Ohios are going for eating stock in the cities and the fields are going to go half planted ' unless something not now on the calendar happens to prevent it, Let us snatch from the big confusion about potatoes, another group of facts. 7 The potato market is not only un= stable from one year to another, but from day to day, from city to city. Here is something that illustrates it. In Chicago a firm charges $10 per car for distributing potatoes—except that it 1s charging $15 this year because the (Continued on page 13)