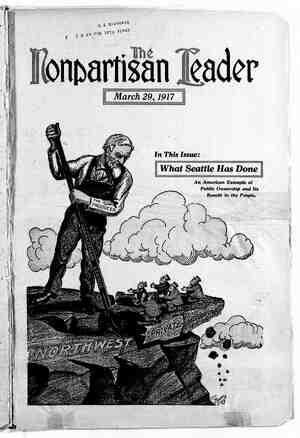

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, March 29, 1917, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

P SIX-MILLION investment of public funds in paying en- terprises. ord. to 20 cents a pound for fish at the re- tail stores. It was the old story of the control of the market at the terminals—the story of the tolls and profits taken by those who added nothing to the value of the products and who charged many times the value of the services they perform- ed. A MIRACLE WORKED BY PUBLIC ENTERPRISE But it is different in Seattle today. Nearly half a million people live in King county, Wash:, in which Seattle is located. Five years ago these peo- ple by their votes created the Seattle Port district and the Port Commission. They voted the commission $6,300,000 in bonds, a debt against the Port district, which comprises all of King county. With this money the Port Commission has restored the harbor of Seattle to the people, and made it a free port. Fourteen separate units in a compre- hensive plan of harbor development have been constructed, all owned and operated by the people. These units include a publicly-owned grain ele- vator, two public}y-owned cold storage plants, several publicly-owned wharves and two publicly-owned ferries. It is easy to enumerate these pub- licly-owned utilities and tell what they cost. But it is difficult by written language to convey the impression one gets by visiting them, talking with the fnen whose vision conceived them and whose genius built them, and watching the vast traffic—the people’s business —handled through these utilities which have opened one of the world’s biggest terminal markets on equal terms to the small and big producer and the small and big shipper. The useless toll takers at the gate have been driven out, like the money changers in the . temple of old, and a free people engage in free commerce. HOW FARMER SMITH TODAY IS TREATED IN SEATTLE Farmer Smith today lands his prod- ucts at a public wharf at Seattle. He pays a quarter of the wharfage he formerly paid. He does not have to sell his products to the commission men at their prices if the price is not right. He can take them to the Seattle public market and sell them direct to the consumers. Or he can store them for a nominal charge in a publicly- owned cold storage plant or warehouse §n which the charge is the same whether he is a big or little producer. If Olson, the fisherman, wants ice, the fish trust does not stick him three ° prices for it. He buys it at a publicly- owned ice plant. He can store his fish indefinitely at a publicly-owned cold storage plant that charges him no more for storage than it charges the big fish companies for the same serv- ice. The charge 1is one-half to a quarter what_it used to be. He buys his supplies and equipment and bait at a publicly-owned supply house that furnishes him what he needs as cheap as the fish trust can equlp its vessels. If the producer happens to be a grain grower or fruit grower the facilities at the terminal are equally capable of taking care of him. The publicly- owned grain elevator for bulk grain Probably the only publicly-owned and operated grain elevator in the United States. It is a part of the system of public warehou: Read the financial rec- It’s the best story of all. and the vast warehouses for sacked grain take care of the grain grower. The latest equipment is available for the fruit grower at the publicly-owned fruit storage warehouse. AN ACTUAL INSTANCE OF HOW IT WORKS Today a fruit grower, a truck garden- er, a_poultry man, a grain grower or a fisherman does not have to dump his product on the market, or throw it in the bay when the pecople are hungry for it. If he likes, he deposits his' product for indefinite storage at rates that are astonishingly small. The minute he deposits them he gets a warehouse receipt, stating the quan- tity and grade. On these receipts he can borrow up to the full value of his produtt without .and difficulty what- ever. I talked with a farmer I met at one of the public warehouses. He had deposited for storage 100 sacks of potatoes, when the market was $3 a sack, and he said that 15 minues after- ward he had borrowed on his warehouse receipt $300, the full value of his potatoes on the market the day he de- posited them. He was then superin- tending the loading of his potatoes on a commission house boat. The com- mission man had sought him out and offered him a good advance over $3 a sack for his product, and he was sell- ing, after he had stored his stuff two months. He reaped the profit on the advance in price and the commission man with the private storage facilities didn’t. A farmer does not have to go to Seattle to get the use of these facilities. No matter how small a farmer or how poor he is the Port of Seattle is not too big to take care of him. He con- signs to the Port, with instructions for storage, and the Port sends him his warehouse receipt. HAY BALING PROFITS AND THE PUBLIC DOCK A" striking example of-how things used to be and how they are was told me by G. F. Nicholson, chief engineer for the Port Commission. “Great quantities of hay are produc- ed on Puget Sound, for which there is a good market in Alaska and other places,” said Mr. Nicholson. *“Much of this hay is produced by farmers who can not afford to put in hay presses, either because they do not have the money or because it is a side line with them and the quantity of hay they pro- . duce does not justify the investment. Of course, the hay has to be baled by presses for shipment by vessel. Hay dealers owned presses and they charged from $5 a ton up for baling it. This was a price that took all the profit out of the business for the farmers. It was intended to do Jjust that, for the hay dealers wanted to buy the hay by the load and make the profit on the baling themselves. The result was the farm- ers could not sell baled hay. They sold their hay in bulk to the hay dealers, who made a profit on baling and on buying and selling besides. “This condition was so oppressive that the farmers in desperation formed a co-operative company; bought two hay presses and built a hay warehouse. This worked all right for a time, but co-operative companies often are badly managed, the members divided into factions and the competition of the big fellows, in the same business for profit, too great to overcome. The farmers were not satisfied with their co-opera- tive proposition and they came to the Port Commission for aid. We investi- gated the conditions in the hay busi- ness and found we could bale hay at a good profit for the Port at $2.50 a ton, half of the former minimum charge. The farmers were satisfied with this price. It was lower than their co-operative company could give them. So they turned over their baling ma- chines to the Port and the Port erect- ‘ed a shed for them on the wharf. Farmers can now sell baled hay and get the extra $2.50 a ton for it that formerly went to dealers. It is baled at our publicly-owned hay baling plant, and after being baled we can store it as long as desired by the farmers at our publicly-owned hay warehouse.” HALF OF TOTAL TONNAGE PASSES OVER PUBLIC TERMINALS These instances will give some idea how publicly-owned terminals can benefit producers and consumers of farm products alike. But this is only a portion of the work of the Port of Seattle through its public terminals. The publicly-owned terminal facilities last year handled half of the total ton« nage that went through Seattle. Five years ago all this great importing and exporting business, this transfer at tidewater from ships to freight cars and from freight cars to ships, was all handléd over private wharves which exacted an excessive and unreasonable toll. When the Port Commission open= ed its first public wharf the average wharfage charge at Seattle was 50 cents a ton. The Port Commission cut it to 20 cents and thereby put Seattle in the running as one of the greatest ports of the world. Business that had been driven away from Seattle by the rapacity of the private interests that controlled the waterfront and the terminal facilities began to come again to this great transfer point together with lots of new business. Private wharf companies were forced to meet the 20-cent rate of the publicly-owned wharves. In 1913 Seattle’s world trade—the value of total tonnage that went over its privately-owned wharves — was $124,130,845, according to U. S. govern- ment figures. In 1916, with the public wharves in operation, the total ton- nage was worth $413,000,000, and half of it went over the docks and through the warehouses owned by the people. Five years-ago Seattle was the twenty-second port of the United States, with Tacoma, its nearby rival, fast outstripping it; but to- day Seattle is the fourth port of the United States. It has paid Seattle to restore its harbor to the " people. . ENTERPRISES OWNED BY PORT OF SEATTLE The Seattle Port commission owns and operates for the people the fol- lowing projects: Smith’s cove terminal wharf and s, wharves and cold storage plants erected by a bond issue voted by the people of King county, Washington, in which Seattle is located. The building back of the elevator is the Hanford street publicly-owned wharf. Modern equipment enables the grain to be conveyed by mchinery out of or into ships or railroad cars. Th 3 D farmers has been so great that the Port Commission has decided to double its capacity. e (he patonagegficite slovator by the SIX 2