Evening Star Newspaper, June 19, 1925, Page 12

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

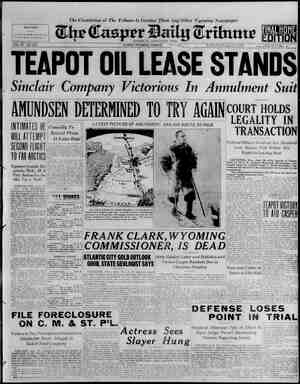

12 Writer With Amundsen Gives Log of Polar Preparations Infinite Care Taken to Assure Success of Epochal Flight—Skilled Men Chosen to Accompany Norwegian Explorer. James B. Wharton, special cor- respondent of The Star and the North American Newspaper Alli- ance, was the only American jour- .malist with the Roald Amuwndsen expedition. Wharton'’s log of the expedition is a complete narrative of the first attempt to reach the Pole by airplane to the arrival at Kings Bay. Here Amundsen him- self took up the log BY JAMES B. WHARTON. Chapter 1. BAY, Sptizbergen.—A small group forms. in the railroad station at Oslo, Nor- way, on the evening of March 31. What's up? What are about? What? Why, it's Roald Amundsen setting out for the North —that white-haired man—there—with the ruddy, seamed face, smiling out genlally through the open window of the carriage—there—with the red rose in his lapel against the back- ground of a thick, gray suit. The slight, dark man beside him is Ells- worth, Lincoln Ellsworth, the Amert- can, who put up half the money for the expedition. They're off to fly to the North Pole. Some stunt, eh” With a half century of vigorous life behind him, 30 of those vears. off and on, spent above the Arctic Circle or below the Antarctic Amundsen Jooks once again toward the North. Those clear, blue eyes, crow’'s-footed about their onter look across the heads of the little crowd into t North and see there snow and ice limitless expanses of blank whitenes: The crowd i ce. It takes only two unoft cing. black beaver- capped n to keep it in order. But it's Most of its members know A en personally. Norway & a tiny land. and the name of Amundsen is a gzreat one. Oslo fsn't like New York: just four newspaper cameramen lined up to make a pic ture for tomorrow morning’s edition. blinds. When eyes regain the crowd is receding, s and shouting, * with the quick, sharp accent of the Norwegian tongue, like the cry hunter baiting his hound. Amundsen turns into the sec- ompartment he shares with Ellsworth. As he slightly thick foreizn Encglish, he “They cheer now, gnything. I don't like that. better wait.” Welcomes Race to Pole. rds fe INGS the people accent of his before I've done They'd m or of his As the ing sun the snowy hilltops and across the clear waters of the fjord, .Amundsen talks But he neve too long, too He cently of past itions in North_and into the South, and confidently of the pres. ent one. He mpetitors, he says. He wani the Pole to be a race and not a walk-away. At Hamar, in_the nighf train pulls -minute while we taurant, just like the one ris- burg, Pa._or any of those stations starting ok into the West, for a bite of supper. His fellow diners recognize Amundsen, ch him with intere: admiration and entertainment—be cause every other face is turned to- ward the thick-set, stalwart man in the thick, gray suit, with the red rose 1n his coat lapel. All through the carly half of the night, ch station where the train wup forms outside his win- A shou of the ple oblige Amundsen to raise his window blind and peer out. until some member of the group, with the familiarity of a littie land. comes forward, shakes the explorer’s hand and w luck. In Norway addresscd as Capt Amundsen, but Amundsen. We step off the train at a reasonable hour into the bright, small northern town of Trondhjem. We see immedi- ately that it was freshened last night by a light fall of snow. The white- painted fronts of its frame houses— houses that might stand in any New England village—glisten in the reflec- tlon of the brilliant northern sunlight. or Mr. alw: as Roald Polar Stamps Popular. The local photographer is at the station to meet us, and after him a kindly gentleman takes us home for break here e of us— Capt. Amundsen, . the ex- pedition’s leader Johan Mathe- son, its physician, and I, corre- spondent of The and tile North American Newspaper Alliance, and the only American represent- ative with the expedition. The rést, with the exception of Schulte Frohlinde, director of the Dor- mier ne nt, and two me- chanics, who will make the next Hbat, are already in Tromso, on the niorthern coast of Norway, which is ‘r-e the expedition's real starting nt. ;Over breakfast, a typical Nor- egian breakfast of coffee and milk, eeses and marmalades and a dozen fferent cold cuts, we hear that, one hour after the sald of polar fight stamps had begun today in Trondhjem, 12,000 of these stamps were bought up f the public. The special stamp, put t in seven varicolored denomina- tons, represents one of the means of nuncing the expedition. After all the troubles Capt. Amundsen has had d@uring the past vear, this bit of news gratifies him :Soon after midday Hong Harald, a Norwegian coastal éamer of under 1,000 tons, which arry us to Tromso. Amundsen < through the hundred students, stinguishable from the other town: f8lk by their tiny, tasseled caps. fter ‘the students have tired of eering Amundsen, they cheer the 1§cal cameraman, as he perches about ¢ steamer’s rail to make a picture ithe crowd of Trondhjem’s citizens ho turned out to see the Arctic ex- orer off on his ambitious project. i There aren't two-dozen passengers I told in the first and second class bin. Besides the four of us—mem- rs of the expedition—the others are all business men, wives and child- R returning to husbands and fathers i various smali, Northern ports. De- pite the smallness of ship and pas- senger list, everything is comfortable id the mess excellent. We are grate- 1 for these last modest comforts, r, beyond Tromso, there will be lfew more. We pick our way swiftly, unerring- Iy among the islands along the West coast of Norway. The air is as bril- llant as the sparkle of the sunbeam through a polished wine glass. The sky a mild blue, the water a clean, light green. The cold is dry and in- vigorating. On_either side of us, a quarter of a mile to starboard and a half mile to port, mountains rise up out of the water, unevenly tossed up hills streaked with snow. The Win- ter has been unusually mild; nowhere havé we vet seen any great depth of snow. Towards sundown we sail directly at what appears a solid range of these low mountains. Suddenly our swhistle blows, a break appears, and We swing into it as an auto takes a we board the down, with the | sharp corner. Our bow nearly scrapes the sheer mass of rock to starboard, our stern just escapes that to port. Now we're crossing a patch-of open sea. No longer protected by the long line of islands, we catch the swell of the Northern North Sea, or the Norwegian Sea, 2s it is sometimes called. We roll a bit as we o to bed. The atmosphere today is even more brilliant than yesterday, although vesterday that would have seemed |incredible. The snow is thicker and | whiter on the mountains, while these | fragments of nature are more numer- {ous, more barren and jagged. It is colder, much colder, yet a dry cold | that does not penetrate. | Amundsen Gay as Boy. Just before midday mess we cross Ithe Arctic Circle, which lies on lati- |tude 66.30 North. This crossing, however, gives us merely an imagin- ative thrill. Had we crossed it on the longest day of the year—on Mid- summer night's eve—we .could have seen, at midnight, the midnight sun. Still, the fact that the Arctic Circle is behind us is proof that we're truly forging North. All day we zig-zag across open water, tying up at wharves here and there, while hoxes, barrels and bags all the most heterogeneous kinds of cargo—are loaded and unloaded. Some of these stops are at towns of one, three, five thousand inhabitants; others are merely steamship company docks, surmounted by a board shanty, its sole relationship with civilization ppearing in the advertisements plas- tered on its front | At every stop we amuse ourselves by going ashore, crunching through the snow to the post office and in- Guiring for Polar stamps. Most of the offices have already sold out; others haven't received any of the issue: at only two can we purchase the limit allowed a single individual —five of each of the seven varieties. We pocket these triumphantly, feel- ing certain that, after we've reached the North Pole, these same stamps will assume more than ordinary worth. Always Capt. Amundsen, as full of | enthu. v, interests Mr. | Ellsworth and me in everything, ani- | mate and inanimate, about us. He | knows the names of all the mountain pass—the Seven Sisters on Man Woman. eider duck swimming alongside. He tells us how these duck breed, in great communities, on the barren |islands, farther North, and how, in |the Spring of each year, the eider |down is gathered from the nests. He points out to us the fishermen's | boats, chugging out to the codfish | grounds, and explains the marvelous manner in which our ship nav through narrow passages and among the rocks and islands which hug the northern coast of Norway. What Capt. Amundsen doesn't know, the doctor tells us. He, one of Norway's | best skifers, has friends every | port we make. He learns all the news and pa in s telligence. The doctor’s an ideal man for the kind of expedition we're about to embark upon. He always has something new to produce, like the box of cakes from some acquaint- ance along the way, which he brought out when we sat over our after-din- ! | ner coffeein the saloon toda During the day’s journey we leave behind us Solstad, Skaalvaer, Nord- vik, Selsoyvik—cold, northern names |all—and at twilight reach Bodo, hud- |dled at the foot of the mountains. Before supper we talk a walk through congruity of snow piled against the | plate glass of electrically lighted win- | dows filled with women's hats, shiny, new shoes and other familiar manu- factured goods. When a man lives in great cities he is inclined t@ think that all the world’s highways lead only to those great cities. He's mistaken. They don’t. Each Bodo is its own center. | The coming of the Kong Harald | here is really no different from the arrival of the Leviathan at New York. No, the ilatter really hasn't nearly so much importance. At 9 o'clock we draw away from the cheerful lights of the town. Out of the lonely group on the pler an individual steps forward, wawes his arm and, in a powerful, Norwegfan | voice that carries clearly through the night air, shouts: “Ro-o0-ald Amundsen, God Lykke!” CHAPTER 11 April 4 when we leave the steamer Kong Harald at Tromso. the early hour here latitude it is already full daylight. The town appears before our sleepy eves as a formless mass of frame houses stretching from the water straight up the side of a snow-covered hill. While the raucous winches of <he little coastal steamer rattle away at their task of unloading odds and ends of freight we crunch through the snow along deserted streets lined with siient houses. We turn a corner, the noise of the winches is lost, and we reach the town's leading hotel—the Grand—an unpretentious, frame house that not yet shows any sign of wake- fulnes: In two hours news begins to come to us. The rest of the expedition isn’t here, as we had thought, but at Nar- vik, some 150 miles to the south, |aboard the Hobby, which is loading the |crated airplane that arrived there by | steamer from the German Dornier plant at Pisa, Italy. Here we find only three of our party—our two me- teorologists and a mechanic from Der- by, England. Roald Amundsen, as usual, is breaking the trail. So, inasmuch as we've gotten ahead of the crowd, we can pause and look at Tromso, which liegon a diminutive isiand hemmed in by ®ater and moun- talns covered with a smooth layer of snow that turns orange and blue when the sun shines upon it. Today the weather is gorgeous, and not at all cold. It is like yesterday, our last day on the water, when we lay out on deck, muffied in our furs, and read. It has been quite as strange a Winter here as farther south. Last New Year day, so we are told, flowers were picked about Tromso. Sleigh Bells Jingle. We feel that we are fairly far North, yet Tromso is a town of some sig. nificance, with a population of 11,000 persons and at least six automobiles, the largest of which belongs to the lo. cal brewery. Tromso is apparently something of a shipping center, lying as it does on the lane of sea traffic int, northern Russia. While from ov land, from across the top of Sweden, come occasional Lapps, = picturesque creatures who wander through here to and from their great herds of rein- deer left in some snow-bedded moun- tain pass hidden from us by the en- circling ranges. Life might be dull for us, despite the merry jingle of sleigh bells on the streets, were we not aware, every moment, that we are on the edge of something stupendous. The realiza- tion of where we are, why we are here and of what the next two momths may hold for us is all absorbing. Then, there is always some article of equip- ment to buy and much profuse enter- tainment to enjoy. The most interesting of the various He's the first to see three | on to us various odds and ends of in- | |snow-packed streets and see the in-| T is 6 o'clock in the morning of | Despite | on the 70th| THE EVENING STAR Arctic equipment we've made the ac- quaintance of here is the Lapland boot, a great, loose, soft leather shoe packed with dried grass—sennegras— to keep the feet warm. The Lapps, jwho developed this type of boot through centuries, wear it only with {the dried grass inside, without even a {sock. It is virtually the same as the { “Muckaluck” shoe worn in Alaska. We are constantly entertained. Capt. Amundsen is living with the leading local apothecary, Fritz Zapffe, who is coming with us as general provisioner for the expedition. Satur- day he hung out a Norwegian flag, in honor of his guest. Sunday it was torn to shreds hy the wind that blew the panes of glass out of my bedroom window. Nothing daunted. Apothe- |cary Zapffe had another flag fiving Monday. Drink Norwegian Way. Mr. Ellsworth and I, living at the Grand Hotel, join our leader for cof- fee every afternoon. And since the Norwegian apparently never drinks a cupof coffee without a liqueur along- side of it, we two strangers to al- | coholic beverages (we are Americans) | have learned to drink after the Nor- | wegian custom. It g { One’s host says “Skoal,” looks you {in the eye, nods, drinks, 1doks you in the eye, renods, and it is over. You must do likewise. Last night, at a formal dinner at the home of the har bormaster, up on the hill, Mr. Ells worth and 1 got it down to perfection. Even Capt. Amundsen admitted that. To April 6, the Farm, the Nor- wegian naval transport, which is to be one of our two ships, arrives in port rom Horton, the naval station of Oslo. We go aboard immediately and see what an uncomfortable voyage we are about to make between here and Kings Bay, Spitzbergen. Yet, we shouldn't complain. We | reckon the duration of this polar ex pedition in months, instead of years, as Roald Amunds 1 Scott—as every Arctic explorer hith- erto has done who depended upon a ship rather than’an airplane. Why, our party is going to be a de luxe one. We're drinking foul-tasting cod liver ofl and are outfitted in furs, but we're merely” going up into the Arctic in early Spring. to return by late Spring. It's the Winter that counts: then’s when the Arctic takes her toll of lives. At last, April 8, the Hobby arrives, and the Amundsen-Ellsworth North Pole flight of 1925 is for the first time completely assembled. We are delight- ed to see them come stamping into the hotel at breakfast time today. The great, dark Viking, Hjalmar Riiser- | Larsen, and his handsome flving mate, Leif Dietrichson. They are “the two who will pilot the two planes toward the North Pole probably around the middle of May. And after them come the rest. Roll of Expedition. Here are the names of the full 20 of us: Capt. Roald Amundsen, Norwegian, and Lincoln Ellsworth, American, leaders of the expeditions Hjalmar Rifser-Larsen, Leif Dietrifhson and Emil Horgen, the first #wo pilots of the planes and the third the reserve pilot, and all lieutenants in the Nor- wegian navy; Oskar Omdahl, Norwe- gian, and Carl Feucht, German, flying mechanics; Adolf Zinsmayer, German, and Fred Green, English, base me. chanics; Heinrich Schulte Frohlinde, German, technical director of Dornier plant at Pisa; Jack Bjerknes, Norwe- glan, and Ernst Calwagen, Swede, me- teorologists; Fritz Gottlieb Zapffe, Nor- wegian, general manager and provi- sioner; Paul Berge, Norwegia operator; Dr. Johan Matheson, | gian, physici inar_Olsen, {gian’ steward: Martin Ronne, ginn, sailmaker; J. Devold, Norwegian, | wireless operator; Fredrik Ramm, Nor- {wegian, journalist, and James B. Whar- {ton, American, journalist | The Farm, Capt. Leif Hagerup, jcarries a crew of Norwegian naval sailors of 32. The Hobby, with Capt. Holm and Capt. Johannessen, designated as “ice captain,” carries a crew of 11. he time of our departure has drawn very near. At the moment I'm drinking a cup of coffee in my corner room of the Grand Hotel, from which {T get a view of the main street of the town. The hallways are in a bustle. | Great boots are stamping on the stair- |way. Dunnage bags, fur coats, rifles, |shotguns, motion picture cameras, |long, slender bundles of skiis are being | swished through the yard aboard the hotel sleigh. Now it is almost midnight. Every- thing is aboard thé Farm, on which !most of us shall voyage away from {here into the north. The moon hangs | mistily over the top of a mountain. The air is laden with the balm of Spring. Outside my window the citi- izens of Tromso are singing a song in { honor of one of Norway's greatest and most beloved sons. At 4 a.m., if our meteorologists say {the weather is right, we hope to get off. We're thrilled—just like kids— with the drama of it. It's bound to be ja_tremendous adventure. The drama jof it is almost as livid as that of the jwar, and—thank God'—it is without the cértainty of terror that the war held for those who really experienced lit. CHAPTER III. UR two little ships, finally loaded with the precious cargo of crated airplane | members and stores for the great adventure, leave Trom- so, Norway, early in the morning of {April 9. We reach the wharf at 5 o'clock, to find a fresh breeze pleas- jantly in action, dissipating the pe- culiar sultriness of the night. With- in a half hour our boat is swinging away from the quay, where a little {group of people has assembled to bid us godspeed and good luck. Most of them have stayed up all night and they are not very demonstrative, be- ing too fagged to give us even a weak cheer. As for us—we, too, had been up all | night, and are so jaded as to be ap- preciative of nothing but sleep. There is none of ws aboard the 400-ton Farm who stops to realize that this {is a momentous occasion; we are |thinking only of finding some place aboard the crowded little steamer where we can stretch out or curl up —and sleep. . We are awakened at 8 o'clock for | coffee. Warmed a little internally, and somewhat refreshed by our cat-nap, we are able to realize how frail is our little craft for these Arctic waters, and Ihow trightfully the ship is loaded for |battling with severe weather. There are 20 men of the crew for- ward in the foc’sle, more than enough for comfort—and vet 6 additional persons, members of the expedition, must join them. Aft there are four cabins normally occupied by the ship's officers, but already doing double serv- fce. The remainder of our passtngers are bunked on the benches and floor of the narrow little saloon. Baggage and freight are strewn everywhere. Boxes and trunks block the companionways. Hindquarters of beef and forequarters of mutton are lashed against every end of spare rig- ging. Skils, dunnage bags, gun cases, crates of provisions, are scattered across the open deck aft. Again we sleep. When we awaken it is early afternoon and we are sur- prised to find the ship riding at anchor in a cove in the lee of a low mountain. The open sea, our eaptain fears, is dangerously rough for ships carrying as deck load the crated parts of two airplanes worth $100,000, on which the whole fate of the expedition depends. Then, while we wait, we lose our companion ship in a sudden fog. There is a council of war,and as the sea has moderated a little, we decided to pro- ceed, believing that the other ship has already pushed on. 1 make my home in the foc'sle and find life there as agreeable as any life can be in a ship’s forward area. The sailors, firemen and engineers, who swing their hammocks here each night are a youthful, clean, happy lot. One - ve-{find any ve- | speculate Franklin Ba; is, of course, an expert on the mouth organ and another is a good tenor. A familiar tune, “Peggy O'Nefll,” trans lated into Norwegian, is their song hit of the moment. Life here is free and easy, but increasingly uncom- fortable as the days pass without a good wash or a change of clothing. Early one evening a severe storm blows up and turns us landsmen—and not a_few of the crew—fairly inside out. success. The foc'sle, all night long, { surpassedghe imagination of the most lurid of movie directors. The mes: tables overturn and c across the floor; a bucket swings off its hook and joins the melee; ham- mocks creek and swing sickeningly; the sea foams at the closed portholes, vibrates throygh our steel sides, slushes down through the open hatch. The next day the weather favors us a trifie. We begin to recover our health. Yet the one worry only yvields to another. We become alarmed as to the whereabouts of the Hobby. Al though the Hobby is 200 tons heavier than the Farm, it is badly loaded, with virtually“all its cargo on deck and | nothing in the hold. Its huge cases of hulls, wings, tails and engines are lashed securely, but one can never know what unexpected forces the vio lence of the sea may produce. After midday mess our ice pilot goes aloft to the crow’s-nest, but falls to trace of the Hobby. We on possible misfortunes which may have befallen her. Not only are the planes aboard her, but four important members of the expe- | dition—Lieuts. Riiser-Larsen and Diet- richson, Fred Green, the Rolls-Royce mechanic, and one of our cinema operators. Ice Hampers Navigation. 1t* grows colder. The thermometer 1s now 10 degrees below frezing. The temperature of the water, 100, is 'W below the freezing point; it only fail to thicken into ice because of its salt. Some snow is flying through the air v s our rigging. For the first time we see the “ice horizon,” or “blink,” a long strip of white along the water’s edge formed by the reflection of the day- light upon the great ice fields. During the night we pass our first ice—an insignificant quantity of slush ice floating on the water. Bear lsiand, the only land between northern Nor- way and Spitzbergen, is passed at mid- night. We are now almost half way to Kings Bay, our destination on the {west coast of the Island of Spitzber- gen. Just after midday a strong wind, blowing up from starboard, kicks up a rough sea that rolls us mightily There is no longer any seasickness among us, but it is uncomfortable for firm on the deck. At 5 o'clock, on latitude 74.30, we meet with some real ice. At first chunks of it, merely flecking the sea. Then thickening into fields of loosely floating cakes. Here and there an odd piece resembling an upturned stalac { tite, wierdly eroded the action of the water, floats calmly by. { One can imagine anything out of | the fantastic_shapes of foating ic(—fl great polar bear swimming througl | the water; an Indian paddling a ca- noe; a white, swathed corpse. Some of the ice is larger now, as long as the beam of our ship. Careful sea- manship is necessary. Our ice pilot, | John Nass, is on top of the wheel- house; Capt. Hagerup on the bridge. We must dodge each chunk, or take it easily along our sides, for we have Ino protection on our bows. The ice looks soft and fleecy, but two-thirds of every chunk is beneath the sur- face. When one does bump us hard, it floats past with a spot of red paint it has taken from our plates. We are now simply on the_ edge of the ice. The great fields lie {o the east of us, between here and the White Sea of Russia, whence the ice is being blown by the prevailing southeast wind. No Sun; No Shadow. There's scarcely any night now. We are experiencing a dull, gray world without the beauty and joy of con- trasts. No sun, no shadows, no night. It is strange to look upward from m: mattress on the foc'sle floor and see gray light coming through the hatch at 11 o'clock at night. From now on we shall have shorter and shorter nights. If we could only have some real sunshine! Every day we hope to see the sun pierce the depressing thickness of clouds that have hung over us since we left behind the north- ern coast of Norway. Easter Sunday—and instead of best clothes we are a bit dirtier than we ‘were yesterday or the day before. Our only Easter parade is a cold proces- sion of ice cakes, passing by almost endlessly. Since last evening it has hindered us seriously. When we get into the thick of a field, our engines are shut down and we drift slowly through, while the ice crunches omin- ously and continuously along our sides. Our position is somewhere off Prince Charles Island, which lies beside Kings Bay. We had hoped to reach port tonight, but with the trouble ‘we have met in the ice jams we are sure to be delayed. The best we can hope for now is to make land early in the morning. Even so, we don’t know whether we can get up. to the quay at the coal mining station there. It may be necessary, if the ice re- mains, to anchor in the midst of it off shore. Easter Sunday—and our only recog- nition of it is a particularly good din- ner, with three kinds of drinks— liquors, wine and Madeira saved from Capt. Amundsen’s South Pole expedi- tion of 1911. Also, during the after- noon, a peculiarly fragrant and potent punch which the Norwegians call “eggdosos,” somewhat like a _thick eggnog. No lilies, but not a bad Easter Sunday at that, We try to sleep, but with slight | reen madly | and icicles form here and there on| a landlubber never to feel his two feet | , WASHINGTON, D. C., FRIDAY, JUNE 19, 1925. CHAPTER 1IV. ODAY we have arrived. The | final preparations for the | great Arctic flight can now begin. The little village of Ny Aalesund, at the end of Kings Bay, consisting of a dozen wooden shanties and a coal mine, is man’s most northerly habitat. Beyond us toward the Pole lie only water, ice and snow, animals and wild fowl. 'Even the Esquimeaux, who live mainly in that portion of Greenland | which lies below the 79th latitude, are south of us. It is 1:45 o'clock in the morning of April 13 when we reach the mouth of Kings Bay and push in until halted by the pack ice. We throw out our anchor on the solid sheet of white and come to rest along its edge. Our position at the moment is the most northerly of any vessel in the world. The Hobby is still somewhere be. hind us—we are surprised and disap- pointed not to find her already here— while a coal boat, also halted on the edge of the ice, lles just a ship's lergth southward. After breakfast a heavil stranger arrives off our hows and tells us that the ice stretches solidly 3 miles to shore. The whole vast ex- panse of it, he says, has formed dur- ing the past two days, when the tem- perature fell to about 19 degrees below freezing. Soon a group of us are following his footmarks toward the landing place at Ny Aalesund. For 10 minutes it feels good to stretch our legs, but after that we find the going more and more tiresome, for the ice Is soft on top and our feet sink into it an inch or more at each step. When we reach land. it takes our last ounce of strength to clamber up the snowy bank and stagger wearily to |the home of the directors of the mining company. They give us whisky, dry stockings and slippers, while our soaked footwear hangs beside the sit- ting room stove. Michael Knutsen and Peter Brandal lare our hosts. Two men with vigor- ous bodles and powerful wills, for they |are the men responsible for keeping alive this northernmost outpost of man. In 1917 they organized the Kings Bay Coal Co. and established the set- tlement of Ny Aalesund. Knutsen, who would be taken for an Irishman any day, learned of the North in one of its best settings. He was in the Klon- dike gold rush of ‘98, when he once bought eggs at $300 a dozen—gold dust quotation—and knew personally Jack London’s character, Swiftwater Bill. Ran|lrk3ble Coal Fields. After they have delivered to Roald Amundsen some mail sent here three vears ago to await his 1, they tell us about their town of Ny Aale- sund. The mines produce the finest coal in the world—its high grade be- ing due to its wealth of oil. Thrown into a stove, it catches fire and burns like wood. About 100,000 tons of it are taken out of the mines each year and shipped south to Norway during the Summer months. I am shown about 50,000 tons lving in great, snow- covered piles, awaiting shipment. The population of the shanty town, |about 400 miners with their families, exist all Winter without communica. tion with the outside world. Pigs are kept and slaughtered for fresh meat, goats are raised to provide milk for the children. During the Summer the steamers bring a supply of stores am- ple to last through the rest of the vear. November, Decémber and Jan- uary must be dismal months in Spitz. bergen. The nights are 24 hours long. For that quarter of a year lights must be used even at mid-day. The vehicular traffic of the place is maintained by six horses—small, shag- By animals of the Russian type—and a three-mile stretch of railway, the northernmost in the world, of course, boasting two antiquated locomotives. Sitting on Top of the World. While we wait for the first shore meal we have had for nearly a week, Knutsen takes a globe from the top of his bookcase and shows us where we are. It is startling. On the little globe, we are but a_thumb’s knuckle away from the pole. Other known land lies farther north—Franz Joseph Land, Northern Greenland and Grantland— but all uninhabited. Above the seven- tv-ninth_latitude, which cuts across Kings Bay, there is no human life. As we look at Knutsen's globe, we realize with amused interest that we are literally “sittin’ on top o' the world.” A The Island of Spitzbergen, recently conceded to Norway, was known to the Vikings as early as 1194. They called it Svalbard, meaning cold coast. Later Russian fur trappers from along the shore of the White Sea safled here and built huts. Norw gian hunters followed the Russian then came the English, the Danes and finally Dutch whalers, who used the island as a base for their whale hunts in the Polar Sea. The latter named it Spitzbergen, or “pointed mountains.” The island has_an extent of 25,000 square -miles. Its mountains and ragged shores maintain a great quan- tity of reindeer, fox and polar bear. Last year 300 huge white bears were killed and their skins taken south. In the encircling ice and water are whale, walrus and various kinds of seal. Gulls, auks and puffin use the island as a nesting place, while inland are many ptarmigan. Only inland 1is there any vegetation. In the evening we return to our boat,-and shortly some one sees smoke out on the Polar Sea. It is& pleas- ant sight and one that stills our wor- ries and fears, for we know that smudge is the Hobby. In 20 min- utes it has stuck its bows into the ice alongside of us. It is a strange sight lying there, its deck piled 20 feet high with the dismembered bodies of two airplanes and the crated wings extend- ing fully 10 feet overside. It resem- bles a pack mule. p Since early morning the coal steam- booted Ship Amundsan’s Rovke | Semmm—— { (irptane Abruzzis Nansen's Grealy's 1q0 ” » e 390 4g0 a3 Dotted line indicates Amundsen’s course from Kings Bay, Spitzbergen, to a point about 150 miles from the magnetic pole. Here their planes landed. The air route of the return to North Cape, where the party boarded a vhaling vessel is shown also, the arrow indicating wherc the whaler abandoned the plane in a storm at Lady er Knut Skaaluren has been des- perately fighting the ice. Steaming forward and backward, it has been breaking a lane through three miles of solid frozen water. We follow 200 vards behind, with the Hobby as far again behind us. Our battle with the ice has become a real life-and- death struggle, because of a quantity of larger bergs that have begun to come fnto the harbor from the open sea. If we cannot force our way into the thinner sheet ice we may easily be crushed. All day long it is a slow, tedious grind, but by evening we are all three alongside the landing. In the morning the unloading of the Hobby begins. We who come from closer to the earth’s girdle are not yet used to the strangeness of Spitzbergen's weather and light. The weather has been can tankerously varfable today. Snow and sunshine every other moment; snow falling upon us and sunlight out on the mountains yonder: a calm when the cold fsn't felt, then a stiff wind that cuts into the flesh. - The unending light is really confus- ifg. Although we shall not see the midnight sun for six days—until April | 20—already it stays light during the full 24 hours. Tonight, sitting in a chair in the middle of my room, I read until a quarter to 12 o'clock. I un- dress and go to bed with the sun- light gilding the mountain peaks, as at dawn In the South. CHAPTER 5 E are now hard at work as- sembling the airplanes for our flight. Amundsen—and all the rest of us—are filled with increasing confidence as we watch our two great flying boats nearing completion—perfect em- bodiments of man’s highest achieve- ment in grace, power and speed. All members of the party are now getting settled ashore, each man find- ing space as best he can wherever a bunk or corner is available in one of the shacks. It is good to be off the overcrowded ship. Luckily, I have landed a room to myself in the hospital, with a com- fortable bed, sheets, and one of those marvelous orwegian stoves which never go out. - My window owerlooks the blue-green edge of a glacier, and bevond are three snow-covered peaks, Thre Crowns-Svea, Dana and Nora,” S0 named in the common lan- guage of the three Scandanavian ccuntries long before the Vikings. A superb view of snow and ice and Jagged mountains bathed 24 hours a day in sunlight. The work of unloading the two air- planes progresses rapidly, beginning early in the morning in a snowstorm, and ending late in the evening under a cloudless, blue sky, with long shad- ows thrown across the, ice and snow. The weather continues clear and cold. Today, April 17, it is 5 degrees above zero Fahrenheit, the coldest we have yet felt. All the assembling work on the planes must be done out in the open and the severe cold is a hardship to the mechanics—Fred Green, from the Rolls-Royce plant in Darby, England; Carl Feucht and Adolph Zinsmayer, from the Dornier plant in Pisha, Italy, headed by the technical director of the factory, Heinrich Schulte-Frohlinde. Still, whatever the weather, we must forge ahead with the assembling. Speed in our final preparations is now essential. Algarsson, the Anglo-Ice- lander, who wants to beat Amundsen to the North Pole in a blimp, shall not catch us napping. We know he is now at Liverpool, with his ship, The Iceland, waiting to set sail for Spitz- bergen. By the time he reaches here we expect to have our planes ready for the hop-off, and perhaps all ready at Danes Island or in open water be- yond if we can find any. Amundsen isn’t worried. He feels that his handi- cap is so great there will scarcely be a race. Algarsson, we hear, intends to descend at the pole by means of a rope ladder, while his blimp flies slow- Iy over the earth’s upper axis. It sounds like a difficult feat. Amundsen and Ellsworth, on the other hand, hope to find a suitable landing place for their planes at the pole, but even if that should be impossible, they can take approximate observations from the traveling airplanes. For either ob- servations from the air or from the ground they are taking along in each plane a regular ship's sextant. Ells- worth, who is a civil engineer, has thoroughly mastered this means of taking observations and will ‘be as now at Liverpool, with his ship The his position should his plane alone reach the area of the pole. Airplanes Are Called “Whale: One of the planes, the N23, is al- ready on land today with its motors partially installed, while the N24's hull lies on the ice beside the Hobby. It is the first opportunity most of us have had to get soma tangible idea of the planes. This Dornier type of fly- ing machine is called theé Wal, Ger- man for whale, and the general ap- pearance of the body couldn’t be bet- ter described in any single word—un- less it were possibly shark. The type is very seaworthy in ap- pearance. The motor gondola, with wings stretching out on either side, stands on top of the hull, with a pro- peller blade fixed on either end. The bottom of the hull is ridged like a rowboat. There are four separate compart- ments, joined by a round dootway, like a porthole. " The first compart- ment is very small, and called the gunnery or observer's cockpit. Then comes a 'ger space, the pilot's cock- pit, with rbom for two men. There are also two driving wheels, enabling either the pilot or mechanic to take over control of the machine instantly. Next toward the rear is the gasoline compartment, containing 10 great cans with a capaclty of about 40 gallons each. At the rear is a compartment for luggage. The planes are made of duralumi- num, a metal as light as aluminum and as strong as steel. The material has been tested down to 100 degrees below zero centigrade without loss of strength, so that it certainly can’'t be affected adversely by any cold that may be encountered on the flight be- tween here and the Pole. The con- tents of the gas tanks will enable the planes to remain in the air 20 hours. As the flying time between the hop-off base and the Pole i reckoned at seven to eight hours, this leaves a fuel safe- ty margin of four to six hours. The boats can land on snow, ice or water. Floats are fitted on elther side of the hull to insure stability on water. In landing on ice unprotected by snow there might be some danger of break- ing the hull. If forced to make such a landing, the safety of the machine will depend upon the delicacy with which its pflot can touch the ground. 108 -Miles per Hour in Speed Test. The total weight of this type of Dornier Wal machine is 7,700 pounds, while it can carry a useful load up to 6,200 pounds. The span of the grace- ful, flying creature is 74 feet, wing area 980 square feet, and In length, from tip to toe, 58 feet. Its maximum performance in our speed tests is 108 miles an hour. but its rate for cruis ing is calculated at between 85 and 90 miles. In the motor gondola are two Rolls-Royce engines, one a tractor and one a pusher, the one for the for- ward propellor and the other for the stern blade, each with a practical horse power of 360. They are timed to run together. Each has 12 cvlin- ders, arranged in two rows inclined at an angle of 60 degrees. Our tests show that these engines eat up gasoline at a rate of 193.6 pints per hour and 6.33 pints of ofl hourly. While there is no chance of cither ofl or gas freezing—our air- plane altitude flights have shown just how much cold qur ofl and gas can stand—the planes will carry on their polar flight Thermix lamps, which heat with a non-combustible flame, and will be used if the planes land at the Pole and the engine oil should thicken These flying twins of ours are, one can see at a glance, just about the most perfect specimens of the art of aircraft manufacture. They are all German machines, built in Italy simply because the Germans are for- bidden, under a clause of the treaty of Versailles, to construct in Ger many any machines of this tvpe Pilots Ready and Eager. Here on the shore of Kings Bay they are being put together by the mechanics who made them, ard they will start off toward the pole piloted by two men who have been flying all kinds of aircraft for the past 10 yvears and have had special training with the Dornjfer Wal recently in Italy. Our pllots and mechanics are all ready and eager for the hop-off. hijalmar Riiser-Larsen, a dark haired Viking who tips the scales at nearly 300 pounds, is a lieutenant in the Norweglan Navy. During the war he was attached to the Royal Naval Air Service in England, and later, in 1921, studied airship navi- gation with the illfated American members of the crew of R-38, the Zeppelin which crashed over Hull, Enkland. He is a competent, confi- dent man, a suitable lieutenant for the intrepid Roald Amundsen, who will ride with him. Leif Dietrichson, also a lieutenant in the Norwegian Navy, is slighter, but still a big man, with light hair and clear blue eves. His experience on the water and in the air is_as thorough as his team-mate's. He, with his native intelligence and vigor, will be a trustworthy pilot for Lin’ coln Ellsworth in the second machine. The flight mechanics will be Feucht, a German, and Omdal, a Norwegian naval lieutenant. The former is considered Dornier's finest mechanic. He saw service during the whole of the war on every air front, including even Turkey; was three times wounded and twice crashed. Several scars of these vari- ous catastrophes remain on his swarthy alert face. He is a_Southern German, his home being in Friedrich- shafen, synonymous with airplanes and airships. Omdal has- been with Amundsen during the past three years on Arctic work. He was aboard the Maud, the ship now lving off the Siberian coast, in which Amundsen tried to drift across the pole. Later Omdal studied flying at Mineoia, flew planes in Alaska, went to England to study the Rolls-Royce motor, and joined the ex- pedition directly from Pisa, where he was working at the Wal factory. It seems safe to predict that, if these two polar planes develop any trouble during the flight, it wont be because of amateurism anywhere. CHAPTER 6. * UR meteorologists are now, per- haps, the busiest men of -the whole expedition. They are on the job 24 hours in the day. Their work never ends, because there is always weather. They keep at their observatlons, their charts and their reports inde: fatigably. They are working in an atmospheric area and under condi- tions hitherto unknown to thelr sci- ence, for no meteorological work on so extensive a scale has ever before been done along the seventy-ninth parallel of latitude, North. Four times dajly these weather sharps fill in a chart of the Arctic winds, down on the surface and also up above at various altitudes, show- ing temperatures, barometric pres- sures and many other important characteristics. All this data is studi- ously assembled and studied in order to forecast that -particular 24-hour period when the planes can best make their polar spurt. Our veteran meteorologists are sur- prised at the quantity and variety of weather to be found in these Arctic regions. They learn several new things every day, and are full of con- versation which means little to the layman but which seems to interest them extremely. Today, however, April 21, they sur. prised ‘us with thg announcement that “Spring is coming!” Despite the three to six feet of snow on their laboratory doorstep; despite the icy blasts which bite our faces and nip our fingers, these men of science de- clare solemnly that it is beginning to be Spring! And, curlously enough, now that they mention it, we begin to agree with them. It isn't as cold as it was, and the sun is warmer and more frequent. The wind s more fitful. During the day furs aren’t necessary so long as you keep in motion. A wind jacket outside a sweater keeps me warm enough. That's the prin- ciple of everyone's dress up here— something outside to break the wind and a bit of wool underneath. With gloves it is the same. Most of us wear woolen mittens, which enable the fingers to keep each other warm, either with a canvas wind covering or woven closely enough to keep the wind outside. Footwear for Arctic Spring. Footwear is the most serious prob- lem, particularly at this time of year, when, some days, the snow begins to | thaw. A man nceds something now that is not only warm, but water- tight. The fancy sports boots which most of us brought along from New York, Lordon, Paris or Berlin are without exception found impractical. They succumb especially to thawing salt’ ice. Nearly everyone has dis- carded all these costly shoes for the cheap Laplander's boot, Which we saw in Tromso for the first time out- side of a museum. Just at present it proves ideal, although later, when the ice and snow turns to water, in May and June, rubber {s needed. The pilots of the two planes, Lieuts. Riiser-Larsen and Dietrichson, are EXPLORERS' DARING WING HIGH PRAISE Norwegian Press Pays Glow- ing Tributes to Amund- sen Party. By the Associated Press. OSLO, Norway, June 19.—The Aft- enposten, commenting on the return to Spitzbergen of Capt. Roald Amund- sen and his Polar expedition, terms the flight the greatest, most interest- ing and most adventurous that could have been made for exploration of the unknown parts of the globe. Ac- cording to the messages received, the paper says, he achieved scientific re- sults beyond any attained by previous Arctic exploration. The fact that the Pole was not reached, the newspaper finds of little importance, since the observations taken b the flvers ex clude the possibility of finding land this side of the Pole. It is expected here that Amundsen will follow out his determination, ex pressed before his polar attempt to Nor on his return from Eulogize Amundsen. This flight, it is believed, will be attempted as soon as his remaining plane is returned to Kings Bay and overhauled. . The Aftemposten expresses the thanks of the nation that Amundsen did not abandon his intention to to the Pole, but held fast to ideals and determinations of his vout “We have no gpeater name than Amundsen’s in Arctic history” the newspaper says. “We have special praise and salutations also for the foreigners in the party. Lincoln Ells worth, the American, and Karl Feucht, the German mechanicia: both of whom risked their lives in the undertaking. We appreciate high- 1y their contribution.” The Tidens Tegn characterizes Amundsen’s trip as “a dash for new knowledge” and says its greates achievement is the fine example o endurance and will power established by the members of the expeditior The Morgenbladet declares tha Amundsen’s observations co m the theory of the Arctic explorer. Dr Fridtjof Nansen, that the North Po! is surrounded by a deep water ba and confirm also the declaration ¢ ‘Admiral Robert E. Peary, the Ameri- can discoverer of the North Pole, thut the pole i covered by ice #nd water “However, the scientific result of the expedition cannot stand compari- son with the personal work of these six men, who held their own against nature’s hinderances by superht toll and succeeded in ing the way back and at the same time mak- ing scientific observations,” the Mor- genbladet adds. busy choosing the best articles for the flight out of the abundant equij ment on hand. Mr. Ellsworth brought from America a great quantity of special equipment—sealskin parkahs gloves, reindeer sleeping bags, kan muckalucks, the Hudson's Bay Company, common American lumberma of thick wool with a rubber galosh over its foot. All these things ar getting a practical test in comparisorn with the native equipment procured in Norway. For the flight, all equip ment must be pared down to a mini mum welght, because the greater part of the useful life of the airplanes must be given over to gasoline. The six men who fly must choose the warmest and lightest, and leave all clse hehind. A single mistake might Cost a life. Tonight, as proof of Sprinds ar- rival, a stiff wind has blown up, bear- ing against our window panes with the slash of a hard-driven rain. The meteorologists give it a velocity of 30 miles an hour. While the temper- ature is only 16 degrees below freez. ing, it feels much colder. Outside the wind cuts into the flesh so keenly that there are not many people to be seen out in the snow. Slow But Sure. A week of life at Kings Bay has gone by. Everyone's efforts or inter ests are concentrated on the assembly of the airplanes which proceeds slowly but surely ‘langsam aber sichert,” say the German mechanics. These days are the ebb tide of action, There was enough of it in getting up this far North so early in the Spring. There will be plenty more when the two planes are ready to take the air Until then we simply keep bus in a dull sort of way. But we do keep busy, all of us for there is no excess personnel on the expedition. None of the 21 of us came along without reason. ‘We have our own home now—a low shanty with snow reaching up to { eaves. Here we meet for meals thrice® daily. The effect of the clear cold air on our appetities keeps the cook, Olsen, busy 12 hou day, at least Our evening meal t ther is some. thing of an occasion. The bareness of the shack is hidden by bunting and flags from the Farm, drinks are served, a phonograph is set going and we sit up until nearly 2 o'clock in the morning, offering skoals to each other. The mechanics keep nearly as busy as the cook. Although there Isn't a great deal of work for them to do the planes having been transported in a fairly complete state—yet th cold slows down what necessary wor they must do. Both flying hoats are now lying side by side on land, lack ing only their wings. These are still up on the Hobby's deck and we can't get them off until the aaluren, the tramp steamer which roke the ic lane for us through the harbor last week, leaves the pier and lets the Hobby take her place. Work for Everybody. Old Martin Ronne, officially desig nated as sailmaker, but quite as truly polar valet to Capt. Amundsen, spends his_days oiling his master's packing and unpacking equipment, and obligingly providing anything for any one who wants anything. from a pair of boots to a length of twine. He. too, has set himself up in the hospital shack, in a little room with a bed and sewing machine in it. Ronne was with Amundsen when he went to the South Pole; his kindly, wrinkled face shows the marks of the years it has weathered in rigorous climates. “There is always work enough for everybody,” he say: ‘We have two cinema operators, be- sides a half-dozen of us who take still photographs. Nearly _every morning and afternoon, or night, for the light is always favorable, there's something_going on to be photo- graphed. There is a constant tempta- tion to spend valuable films on that which has no closer connection with the expedition than the scenery, which is very beautiful. Every hour of the day the land- scape seems to change aspect with the ‘variation of the sun around our horizon, The sun, of course, at this latitude travels almost horizontally, instead of vertically, around us. At night the view of the mountains is finest, when the light is soft and yellow. By day it has a- white hard- ness that forces us to wear yellow glasses. (Copyright, 1025, in United States, Can- ada, South America and Japan by 'North Ameérican Newspaper Alliance: in England by Central in Germany and Austria by Verlag Ul in France by Petit Pa- risien: in Italy by Corriere della Sera: in the Nothfirlu;dl by Able\lwo Rnu\en: sche Cour- ant; in y Dagens Nyheter: in Den- mark by Politiken: in Finland by Helsingin i in N orwegian Sanomat: in Nerway by N Club. Al rights reserved.) .