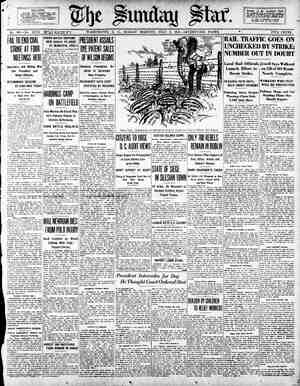

Evening Star Newspaper, July 2, 1922, Page 56

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

'Z" P LEARNED my fighting from my mother when I Was very youns. We slept In a lumber yard on the river front and by day hunted “for food along the wharves. When we got it the other tramp dogs would try to take it off us, and then it was wonderful to see mother fly at them and drive them away. When 1 was able to fight we kept the whole river range to ourselves. T had the genu- ine long “punishing” jaw, so ‘mother said, anq there wasn't a man or a dog that dared worry us Those were “happy days. those were; and we lived well. share and share alike. But one day a pack of curs we dfove off snarled back some new names at her. and mother dropped her head and ran, just as though they had whipped us. and though I hunted for her in every court and alley and ‘back street of Montreal, I never found her. One night a month after mother ran away I asked Guardian, the old blind mastiff, whose master is the night watchman on our slip, what it all meant. Then he tells me that my father was a great and noble gentleman from London. “Your father had twenty-two registered ancestors, had your father.” old Guardian says, “and in him was the best bull-terrier blood of England, the most ancientest. the most royal; the winning ‘blue-ribbon’ blood that breed champions. But. | you see. the trouble is, Kid—well. you ! see, Kid, the trouble is—your moth- er. “T¥ 1 said. and I got up and holding my head and tail high in the air. But I wanted to see mother that very minute and tell her that I didn’t care. * ¥ kX M[OTHER s what T am, a street 4 there's no roval blood in nor is she like that nor—and that's the worst—she's not even like me. For while I, when I'm washed for a fight, am as white as clean snow. she. and this is our trouble, she—my mother is a black and tan When mother hid herself from me I was twelve months old and able to take care of myself, and one day lhei master pulled me out of a street fight | 1 legs and kicked me good. au want to fight. do you?' says “I'll give you all the fighting you he. want!” he savs. and he kicks me again. So I knew he was my master, and 1 followed him home. Since that day T've pullad off many fights for him. and they've hrought dogs from all over the provined to have a go at me. but up to that night none under thirty pounds had ever downed me. But that night so soon as they car- ried me Into the ring I saw the dog | was overweight and that I was no match for him. It was asking too much of a puppy. The ring was in a hall back of a public house. I lay in the master's lap, wrapped in my blankef, and. while the men folks were a-flashing | their money and taking their last drink at the bar, a little Irish groom in gaiters came up to me and give me the back of his hand to smeil and scratched me behind the ears. “You poor litt'a pup” says “You haven't no show,” he says. “That brute in the taproom, he'll eat your heart out.” he. * ok % % 1 R could just remember what | did happen in that ring. He gave me no time to spring. He fell on me like a horse. He closed deeper and deeper on my throat, and every- thing went black and red and burst- ing; and then the handlers pulled him off and the master give me a kick that brought me to. But 1 couldn’t move none. “He's a cur!” yells the master, “a, sneaking. cowardly cur” And he kicks me again in the lower ribs, so that T go sliding across the sawdust. He picked me up by the tail and swung me for the men folks to see. “Does any gentleman here want to buy a dog.” he says, “to make into sausage meat?’ he says. “That's all he's good for.” Then I heard the little Irish groom ‘Il give you ten bob for the the master, ‘make 1t “Ten and his voice sobers a bit; shillings!" says two pounds and he's yours, But the pals rushed in again. Don't you be a fool, Jerry, “You'll be sorry for this when they sa vou're sober. That dog’s got good Dblood in him, that dog has. Why, his father—that very dog's father—is Regent Royal, son of champion Re- gent Monarch, champion bull-terrier of England for four years.™ But the master calls out, “Yes, his father was Regent Royal; who's say- ing he wasn't? But the pup's a cow- ardly cur, that's what his pup is, and why —TI'll tell you—because his mother was a black-and-tan street dog. that's why Some way 1 threw myself out of the master's grip and fell at his feet and turned over and fastened all my teeth in his ankle, just across the bone. When 1 woke, after the pals had kicked me off him, I was in the smoking car of a railroad train lying in the lap of the little groom, and he was rubbing my open wounds with a greasy, vellow stuff, exquisite to the smell and most agreeable to lick off. “Well, what's your name—Nolan? Well, Nolan, these references are sat- isfactory,” said the young gentleman my new master called “Mr. Wyndham, sir” “I'll take you on as second man, You can begin today.” My new master shuffied his feet. “Thank you, sir,” says he. Then he choked. “I have a little dawg, sir,” Bays he. “You can't kee him.” ‘Wyndham, sir,”" very short. Es only 2 puppy. sir” says my new master; “'e wouldn't go outside the stables, sir. Tt's not that,” says “Mr. Wyndham, sir” “I have a large kennel of very fine dogs They're the best of their breed in America. I don't allow strange dogs on the premises.” ERE ¢THE master shakes His head, and !4 motions me with his cap, and 1 erept out from behind the door. “I'm sorry, sir,” says the master. “Then 1 san't take the place. I can't getalong without the dog, sir. “Mr Wyndham, sir,” looked at me that flerce that I guessed he was go- ing to whip me, 50 1 turned over on ‘gmy dack and begged with my legs and tail, ‘ . *Wny, you bDeat him!™ says Mr. Wyndham, sir,* very stéri. - & says “Mr. | Trophy House, “No fear!” the master “He never learnt that from me!" He picked me up in his arms, and to show “Mr. Wyndham, sir.” how well 1 loved the master I bit his chin and hands. < “Mr. Wyncham, sir,” turned over the letters the master had given him. “Well, these references certainly are very strong,” he says. “I guess I'll Iet the dog stay this time. Only see you keep him away from the ken- nels—or you'll both go.” hank you, sif," says the master, grinning like a cat when she's safe be- hind the area railing. “He's not a bad bull terrier.,” says “Mr. Wyndham, sir,” “feeling my head. “Not that I know much about the smooth-coated breeds. My dogs are St. Bernards. What's the matter with his ears?” he says. “They're chewed to pieces. Is this a fighting dog?” he asks, quick and rough-ltke. I ran to the master and hung down my head modest-like, waifing for him to tell my list of battles, but the mas- ter he coughs In his cap most painful. “Fightin® dog. sir," he cries. “Lor’ bless you, sir, 'ees just a puppy, sir, same as you see; a pet dog. 8o to speak.” “Well, you keep him away from my St. Bernards,” says “Mr. Wyndham, sir" or they might make a mouthful of him." “Yes. sir, that they might,”" says the master. But when we gets outside he slaps his knee and winks at me most sociable. The master's new home was in the country, in a province they called Long Island. “Now. Kid." says the master, “you've &0t to understand this. When I whistle it means you're mot to go out of th ‘ere vard. These stables is your jall. And if you leave ‘em I'll have to leave ‘em, too, and over the seas., in the County Mayo, an old mother will ‘ave to leave her bit of a cottage. For two pounds I must be sending her every month, or she'll have naught to eat, nor no thatch over -er head; so I can't lose my place, Kid, an' see you don't lose it for me. You must keep away from the kennels,” says he. “The ken- nels are for the quality. I wouldn't take a litter of them woolly dogs for one wag of vour tail. Kid, but for all that they are your betters. same as the gentry up In the big house are my bet- ters. I know my place and keep away from the gentry. and you keep away from the champions. So T never goes out of the stables. All day I just lay in the sun on the stone flags, licking my Jaws. * * k X ! ! NE day the coachman says that| the little lady they called Miss Dorothy had come back from Rcthl and that same morning she runs over to the stables to pat her ponies, god she sees me. “Oh, what a nice little, white little dog, said she; saye she. hat's my dog, miss,”" says the mas- & me is Kid."” and I ran up to her most polite and licks her fingers. You must eome with me and call on my new pupples,” says she, picking me up in her arms and starting off with me. “whose little dog are “Oh, but please, miss,” cries Nolan, “Mr. Wyndham give orders that the Kid's not to go to the kennels." “That'll be all right,”” says the little lady; “they're my kennels, too. And the puppies will like to play with him." You wouldn't belleve me if I was to tell you of the style of them quality dogs. There was forty of them, but each one had his own house and a yard —and a cot and a drinking basin all to hisself. They had servants standing ‘round waiting to feed ‘em when they i was hungry. and valets to wash ‘em; and they had their hair combed and brushed like the grooms must when the go out on the box. Even the pup- pies had overcoats with their names on ‘em in blue letters, and the name of each of those they called champions was painted up fine over his front door. But they were very proud and haughty dogs, and looked only once at me, and then sniffed in the air. The little lady's own dog was an old gentleman bull dog and ‘e turned quite kind and affable and showed me about. “Jimmy Jocks,” Miss Dorothy called him, but, owing to his weight, he walk- ed most dignified and slow. and looked much too proud and handsome for such a siliy name. “That's the runway. and that's the says he to me, “and that over there is the hospital.” “And which of these is your ‘ouse, sir?” asks I, wishing to be respect- ful. “I don't live in the kennels, says he, most contemptuous. “I am a house dog. I sleép in Miss Doro- thy's room. And at lunch I'm let in with the family. I suppose” “says he. speaking very slow and impres- sive, “I suppose I'm the ugliest bull dcg in America.” and as he seemed to be so pleased to think hisself so, 1 sald, “Yes, sir, you certainly are the ugliest ever I see.” “But I couldn’t hurt 'em, as you say.” he goes on. “I'm too old,” he says; “I haven't any teeth. The last| time one of those grizzly bears” said he, glaring at the big St. Ber- nards, “took hold of me, he nearly was my death,” says he. “He rolled me around In the dirt, he did,” says Jimmy Jocks, “an’ I couldn't get up. It was low.” says Jimmy Jocks, mak- ing a face like he had a bad taste in his mouth. At this we had come to a little honse off by itself, and Jimmy Jocks invites me in. “This is their trophy room,” he says, “where they keep their prizes. “Mine,* he says, rather grand like, * re on the sideboard.” * K X X < THE trophy room was as wonderful as any public house 1 ever see. On the walls was pictures of nothing but beautiful St. Bernard dogs, and rows and rows of blue and red and yellow ribbons. And there was many shining cups on the shelves, which Jimmy Jocks told me weré prizes won by the champions. “Now, sir, might I ask you, sit,” says I, “wot is a champion?” At that he panted and breathed so hard I thought he would bust hisself. ‘My dear young friend!” says he. ‘Wheréver have you been educated? A champion is a—a champion” he| says. “He must win nine blue rib-| bons in the ‘open’ cl You follow me—that Is—against all comers. Then he has the title before his name, and they put his photograph in the sport- ing papers. You know, of course, that 1 am a champion,” says he. am Champion Woodstock Wisard III, and the two other Woodstock ‘Wisards, my father and uncle, were both champlons’ " THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, MOTHER! I'M THE KID! I'M COMING TO YOU, MOTHER, I'M COMING.” “But 1 thought your name was Jimmy Jocks," 1 said. He laughs right out at that. “That's my Mennel name, not my registered name,” he says. “Why you certainly know that every dog has two names. Now, what's your registered name and number, for instance?” says he. “I've only got one name,” I says. “Just Kid." Woodstock Wizard puffs at that and wrinkles up hls forehead and pops out his eyes. “Who are your people “Where is your home?" says he. “At the stable, sir,” I sald. “My master is the second groom." At that Woodstock Wizard 1II looks at me for quite a bit without winking. “Oh, well, says he at last, “you're a very clvil young dog,” says he, “and 1 have known many bull terriers that were champions.” says he. Then he waddles off, leaving me alone and very sad, for he was the first dog in many days that had spoken to me. But since he showed, meeing that I was a stable dog. he didn't want my company, 1 waited for him to get well away. * K K X THE trophy house was quite & bit from the kennels, and as I left it 1 see Miss Dorothy and Woodstock Wizard 111 walking back toward them, and that a fine, big St. Bernard, his name was Champion Red Elfberg, had broke his chain. and was run- ning their way. When he reaches o0ld Jimmy Jocks he lets out a roar, and he makes three leaps for him. 0ld Jimmy Jocks was about a fourth his size, but he plants his feet and curves his back, and his hair goes up around his neck like a collar. But he never had no show at mno time, for the grizzly bear. as Jimmy Jocks had called him, lights on old Jimmy's back and tries to break it, and old Jimmy Jocks snaps his gums and claws the grass, panting and groaning awful. The odds was all that Woodstock Wizard IIT was go- ing to be killed. But Woodstock Wizard I1I, who was underneath, sees me through the dust, and calls very faint, “Help, you!" he says. “Take him in the hindleg,” he sa “He's murdering me.” he says. And then the little Miss Dorothy, who was crying and calling to the kennelmen, catches at the Red EIf- berg's hind legs to pull him off, and the brute turns his big head and snaps at her. So I went up under him, and my long “punishing jaw" locked on his wooly throat, and my back teeth met. I couldn't shake him, but I shook myself, and thirty pounds of welght tore at his wind- pipes. I couldn’t see nothing for his long hair, but I heard Jimmy Jocks puffing and blowing on one side, and munching the brute’s leg with his old gums. When the Red Elfberg was out and down 1 had to run, or those kenpel men would have had my life. Well, “Mr. Wyndham, sir,” comes raging to the “stables and sald I'i half killed his Dbest prize winner, and he gives the master his notice. But Miss Dorothy she says it was his Red Elfberg whit began the fight, and that I'd saved Jimmy's life, and that old Jimmy Jocks was worth more to hér than all the St. Bernards in the Swiss mountains—wheérever they be. So when he heard that side of it, “Mr. Wyndham, sir,” told us that if Nolan put me on a chain we could stay. * x % % ® never worn a chaln before, but that was the least of it. For the quality dogs couldn’t forgive my whipping their champion, and they came to the fence between the kennels and the stables, and laughed through thé bars, barking most cruel words at me. I couldn’t understand how théy found it out, but théy knéw. Jimmy Jocks said the grooms had boasted to the kénnél men that I .was a son of Regent Royal, ‘aad that when thakeassl men asked who was my mother they had had to tell them that, too. “These misalliances will occur,” sald Jimmy Jocks, “but no well-bred dog,” saye he, looking most scornful at the St. Bernards, “would refer to your misfortune before you, certainly not cast it In vour face. I, myself, remember your father's father, when he made his debut at the Cryatal Palace. He took four blue ribbons and three specials.” | But the jeers cut into my heart, and the chain bore heavy on my spirit. About a month after my fight the word was passed through the ken- nels that the New York show was coming, and such golngs on as fol- lowed I never did see. The kennel men rubbed ‘em and scrubbed ‘em and trims their hair and curls aad combs it, and some dogs they fatted, and some they starved. No one talked SIDE from the songs that have left a lasting impression upon those who grew up dur- ing the war and immediately following it, there are many which have left a less stirring appeal and which will also live in the dark memorles of that would-be forgotten period. Among these I refer to “Lit- tle Giffin of Tennessee,” written im- mediately after the war by Dr. Frank 0. Ticknor of Columbus, Ga. Little Giffin went to the front when it was aptly said that the demand for sol- diers was robbing the cradle—went before he was sixteen and was ter- ribly wounded. Dr. Ticknor took him to his beautiful country home near Columbus, Ga., for treatment, and as soon as the boy was able to get about he slipped away and rejoined the army—this time to receive the wound which proved fatal. Dr. Tick- nor tells the story in these spirited lines: Out of the focal and foremost fire, Out of the hospital walls dire, Smitten of grapeshot and gangrene (Eighteenth battle and he sixteen Bpecter, such as you seldom see, Little Giffin of Tennessee. ““Take him and welcome!" the surgeon said: “Little the doctor can help the dead.” 8o we took him and brought him where The balm was sweet in the summef air: And we laid him down on a wholesome béd— Utter Lazarus, heel to head! And we watched the war with abated breath, Skeleton boy against skeleton death. Months of torture, how many such? Weary weeks of the stick and crutch; And still & glint of the steel-blue eye Told of a spirit that wouldn't die. Word of gloom from the war one da. Johnston pressed at the front, they say. Little Gifin was up and away; A tear—his first—as he bade good-bye, Dimmed the glint of his steel-blue eve, “I'll write if spared!” There was news of the fight: But none of Gifin—he did not write. 1 sometimes fancy that, were I king Of the princely Knights of the Golden Ring, With the song of the minstrel in mine ear, And the tender legend that trembles here, 1'0 give the best on his bended knee, The whitest soul of my chivalry, For Little Giffin of Tennessee. PR F course, during the dark years while the civil war lasted many beautiful and touching things were written which will tive as long as our literature endures. Our beloved Paul H. Hayne contributed his full share to the literature of that period, and his close friend and cotempo- rary, the immortal Timrod, likewise left his ‘gift to the cause which was lost. Timrod's “Carolina” has some- thing of the military aignity and tread of “My Maryland,” but the poem is too long to be quotéd here. However, one cannot resist giving a part of that deathless “ode” he wrote and which was sung on the occasion of décorating the graves of the Con- federate dead at Magnolia cemetery, Charleston, S. C., in 1867: Sleep sweetly fn your Bumble graves Sleep, martyts of & fallen case; Thogh yet fio marble column craves The plighim bere to pause. In seeds of laurel in the earth The blossom of your fame Ia biowa, And somewhere, waiting for its birth, The shaft 1s in the stone! Meanwhile, béhalf the tardy sears - Which keep in tedst your Storied tombs, l l OUR FAMOUS SONGS Little Giffin NE of the classics growing out of the clvil war is “All Qulet Along the Potomac Tonight,” the authorship of which has long been In dispute. And yet It matters little as to who wrote the glowing lines, for the poem is non-partisan and deals with a phase of military life which endears it to all. The poem took a strong hold upon the public heart and even to this later date has never lost any of its fevered Interest: “"All quiet along the Potomac,' they say, “‘Except now and then a stray picket 1Is shot, as he walks on his beat to and ffo, By a rifieman hid in the thicket, "Tis nothing: a private or two, now and then, Will not count in the news of the battle; Not an officer lost—only one of the men, Moaning out, all slone, the death rattle. All quiet along the Potomac tonight, Where the soldiers lie peacefully dream- ing; Their tents In the rays of the clear autul ‘moon, Of the light of the watch-fires beamicg, A tremulous sigh, as the gentle night wind Through the forest leaves softly is creep- ing; While stars up above, with their gittering eyes, Keep guard—for the army in sleeping. The Sponge Animal. IF the sponge as brought up fresh from the seashore were a familiar object few persons would be in doubt as to Mts being an animal. When fresh it is a fleshy-looking substance covered with a firm skin. Its ca ities are filled with a gelatinous sub- stance called “milk." American sponges and those of all other parts of the world are inferior to the spongés of the eastern shore of the Mediterraneon. The finest of all sponges is the Turkey toilet sponge, which is cup-shaped. The American sponge most nearly ap- proaching it in quality is the West Indian glove sponge. Traveler’s-Tree Myth. MONG the romantic stories of far- oft lands that have long main- tained their circulation and com- manded more or less belief is that of the “traveler's tree,” credited with posséssing a réservolt of pure water fitted to save the lives of wanderers ih, the desert. An American ecientist declares, from his own experience, that the tree grows only in the neigh- borhood of swamps and springs, and that, although it has a considerable amount of water in a hollow at the base of its leaf, the water possesses a disagreeable vegetable taste and, of course, 18 inferlor to othér water found in the vicinity. Solidified Petroleum. A.\X American consular officer in Frince has furnished some inter- esting details concerning the manufac- ture and use of petroleum briguets as fuel. It appears that these briquets weigh only half &s much as coal, and that they produce twice as much heat. They keep indefinitely in good condi- tion, it is said; are in no way danger- ous, give off no smoke or odor, and burn with a very white flame, eight or ten inches high. They consist 6f petro- leum, éither e¢rude or refined, mixed with certain chemicals, the precise na- ture of which is & trade secret, and #0lidified In molds under a pressure of ‘|¥ou wish, I'll enter your dog, |of nothing but the show, and the chances ‘bur kennels” the otifer kennels. One day Miss Dorothy came to the stables with “Mr. Wyndbham, sir,” and| seeing me chained up and miserable, she takes‘me in her arms. You poor little tyke says she. “It's crael to tie him up so: he's eat- ing his heart out, Nolan,” she sa: “I den’t knew nothing about bull-ter- “but I think Kid's got good points,” says she, “and you ought to show him. Jimmy Jocks has three legs on the Rensselaer cup now, and I'm going to show him this time s0 that he can get the fourth, and if too. How would you like that, Kid?" says she. “How would you like to see the most beautiful dogs in the world? Maybe, you'd meet a pal or two,” says she. “It would cheer you up, wouldn't it, K1d?” says she. “Mr. Wyndham, sir,” laughs and takes out a plece of blue paper, and sits down at the head-groom’s table. “What's the name of the father of your dog, Nolan?” says he. And Nolan says, “The man I got him off told me he was & son of Champion Regent had against Royal, sir. But it don't seem likely, does it?" says Nalon. “It does not!" says "Mr. Wyndham, sir,” short-like. “Sire unknown,” says “Mr. Wynd- ham, sir,” and writes it down. “Date of birth?’ asks “Mr. Wynd- ham, sir.” “]——I—— unknown, sir," says No- lan, getting very red, and I drops my head and tail. And “Mr. Wyndham, »ir,” writes that down. ‘Mother's name?” says “Mr. Wynd- ham, sl “She was a—unknown,” says the master. And I licks his hand. “Dam unknown,” says “Mr. Wynd- ham, sir,” and writes it down. Then he reads out loud: “Sire unknown, dam unknown, breeder unknown, date of birth unknown. You'd better call him the “Great Unknown,” says he. “Who's paying his entrance fee?” “I am,” says Miss Dorothy. * % % % ‘WO weeks after we all got on a 4 train for New York; Jimmy Jocks and me following Nolan in the smok- ing car, and twenty-two of the St Bernards, In boxes and crates, and on chains and leashes. But I hated to go. 1 knew I was no “show"” dog, even though Miss Doro- thy and the master did their best to keep me from shaming them. For before we set out Miss Dorothy brings a man from town who scrub- bed and rubbed me, and sand-papered my tail and shaved my ears with the master's razor, 80 you could most see clear through ‘em, and sprinkles me over with pipe clay, till I shines like a Tommy's cross belts. “Upon my word!" says Jimmy Jocks when he first sees me. “What a swell you are! You're the image of your granddad when he made his debut at the Crystal Palace. He took four firsts and three specials.” But I knew he was only trying to throw heart into’ me. We came to a Garden, which it was not, but the biggest hall in the world. Inside there was lines of benches a few miles long, and on them sat every dog in the world and they was all shouting and barking and howling so vicious that my heart stopped beat- ing. Jimmy Jocks was chained just hehind me, and he said he never een s0 fine a show. “That's a hot class youre In, my lad" he says, |100king over into my street, where there was thirty bull terriers. They was all as white as créam, and each 5o beautiful that if I could have broke my chain I would have run all the way home and hid myselt under the horse-trough. All night long they talked and sang, and passed greetings with old pals, and the home-sick puppies howled dismal. Next morning, when Miss Dorothy comes and gives me water in a pan, I begs and begs her to take me home, but she can't understand. Then suddenly men comes hurrying down our street and begins to brush the beautiful bull terriers, and Nolan rubs me with a towel and Miss Doro- thy tweaks my ears between her gloves, so that the blood rufs to ‘em and they turn pink and stand up straight and sharp. ow, then, Nolan,” says she, “keep his head up—and never let the judge lose sight of him.” Whea I hears that my legs break under me, for I know all about judges. Twice the old mas. ter goes up before the judge for fight- ing me with other dogs, and the judge promises him if he ever does it again he'll chain him up in jall. I knew he'd find me out. A judgé can't be fooled by no pipeclay. He can see right through you. EE 7THE ludging ring where the judge holds out was so llke a fighting pit that when I came in it and find six other dogs there L. springs into po- sition, so that when they lets go I can defend myself. But the master smooths down my hair and whispers, “Hold 'ard, Kid, hold ‘ard. This ain't a fight,” eays he. “Look your pret- he whispers. “Please, Kid, look your prettiest,” and he pulls my leash tight. There was millions of people a- watching us from the railin and three of our kennel men, too, mak- ing fun of Nolan and me, and Miss Dorothy with her eyes so big that I thought she was a-going to cry. The judge, he was a flerce-looking man with specs on his nose, and a red beard. The judge looks at us careless like, and then stops and glares through his specs, and I knew it was all up with me. He just waves his hand toward the corner of the ring. “Take him away,” he says to the master. “Over there and keep him away,” and he turns and looks most solemn at the six beautiful bull terriers. I don't know how I crawled to that corner. The kennél men they slapped the rail With their hands and laughed at the master. But little Miss Dorothy she presses her 1ips tight, and I see tears rolling from her eyes. The master, he | hangs his head like he had heen‘ waipped. 1 felt most sorry for him' than all. If the judge had ordered me right out it wouldn't have disgraced us so, but it was keeping me there while he was judging the high-bred dogs that hurt 8o hard, And his doing it so quick without ne doubt nor questions. You can't fool the judges. They ses insides you. But he guu:‘t make up his mind aboat them high-bred dogs. scowls at ‘em, and he glares at ‘em. And he feels of ‘em, and orders ‘em to run about. And Nolan leans against the ralls, with his head hung down, and pats me. And Miss Dorothy comes over beside him, but don't say noth- ing. A man on the other side of the rail he says to the manster: “The judge don’t like your dog?" “No." sald the master. “Have you ever shown him before?" says the man. g “No,” says the master, never show him again. says the master, ‘an’ he suits me! And J don’t care what no judges think.” And when he says them kind words I licks his hand most grateful. * *x % % THE judge had two of the six dogs on a little platform in the middle of the ring, and he had chased the four other dogs Into the corners, where they was letting on they didn't care, same as Nolan was. At last the judge he gives a sigh, and brushes the sawdust off his knees and goes to the table In the ring, where there was a man keeping score, and heaps and heaps of blue and gold and red and yellow ribbons. And the judge picks up a bunch of ‘em and walks to the two gentlemen who was holding the beautiful dogs, and he says to each “What's his num- ber?” and he hands each gentleman a ribbon. And then he turns sharp, and comes straight at the master. “What's his number?” says the -_( \iTh e Bar Sini Ster——Wyndham 'Kid’s Meteoric Career Among the Canine Champions——By Richard Harding DaViS “ana TH He's my dog."” judge. And Miss Dorothy claps her hands and cries out like she was laughing. “Three twenty-six,” and the judge writes it down and shoves master the blue ribbon. I bit the master and 1 jumps and bit Miss Dorothy and I waggled so hard that the master couldn’t hold me. When I get to the gate Miss Dorothy snatches me up and kisses me between the ears, right beéfore millions of people, and they both hold me %o tight that I didn't know which of them was carrying me. We sat down together and we all three just talked as fast as we could. They was so pleased that I couldn't help feeling proud of myself, and I barked and jumped and leaped about 80 gay that all the bull terriers in our street stretched on their chains and howled at me. But Jimmy Jocks he leaned over from his bench and says, “Well done, Kid. Didn't 1 tell you so? I saw your grandfather make his debut at the Crystal—" “Yes, sir, u did. sir,” says I, for 1 have no love for the men of my family. * k x % A GENTLEMAN with a showing 4% leash around his neck comes up just then and looks at me very critl- cal. “Nice dog vou've got. Miss Wyndham.” says he. “Would you care to sell him? “He's not my dog.’ oth were. “He's not for sale, sir,” says the maater, and J was that glad. “Oh, he’s yours, is he?” says the gentleman, looking hard at Nolan “Well, I'll give you $100 for him," says he careless like. “Thank you, sir, he's not for sale,” says Nolan, but his eyes get very big. The gentleman, he walked away, but he talks to a man in a golf cap and by and by the man comes along our street and stops in front of me. “This your dog?" says he to “Pity he's so leggy.” says he. had a good tail and a longer stop and his ears were set higher he'd be a good dog. As he Is, I'll give $50 for him.” But Miss Dorothy laughs and says: “You're Mr. Polk’s kennel man, 1 be- lieve. Well, you tell Mr. Polk for me that the dog's not for sale now any more than he was five minutes ago, and that when he is he'll have to bid against me for him.” The man looks foolish at that, but he turns to Nolan quick like. “I'll give you three hundred for him,” he says. “Oh, indeed!” whispers Miss Dor- othy, like she was talking to herself. “That's it, Is it," and she turns and looks at me. Nolan, he holds me tight. “He's not for sale,” he growls, and the man looks black and walks away. “Why, Nolan!" cries Miss Dorothy, “Mr. Polk knows more about bull terriers than any amateur in Amer- fca. What can he mean? Why, Kid is no more than a puppy! Three hundred dollars for a puppy!” “And he ain't no thoroughbred, neithér!"” cries the master. “He's ‘unknown,' ain't he?" But at that a gentleman run$ up calling, “Three twenty-six, three twenty-six,” and Miss Dorothy says, “Here he is, what is it? “The winner's class,” says the gen- tleman. “Hurry, pleate. The judge is waiting for him. I'm afraid it's only a form for your dog, but the judge wants all the winners, puppy class eve: We had got to the gate and the gentleman there was writing down my number. “Who won the open? Dorothy. “Oh, who would?” laughs the gen- tleman. “The old champion, of course. He's won for three years now. There he is” and he points to a dog that's standing proud and haughty on the platform in the mid- dle of the ring. * % k% says Miss Dor- holding me tight. *“I wish he asks Miss NEVER see s0 bsautiful a dog. so fine and clean and noble. Aside of him, we other dogs, even though we had a blue ribbon apiece, seémed like lumps of mud. He was a royal gentleman, a king, he was, and no one around the ring pointed at no other dog but him. “Oh, what a picture/ Dorothy. “Who Is he? says she, looking in her book. “I don't keep up with terriers ™ “Oh, you know him,” says the gen- tleman. “He is the champion of champiens. Regent Royal The master's face went red. *And this 1s Regent Royal's son” cries he, and he plants me on the platform next my father. 1 trembled so that 1 near fall. But my father he never looked at me. He only smiled, the same sleepy smile, and he still kéep his eyes ha!f- shut, like as no one, no, not even his son, was worth his lookin' at. The judge, he didn’t let me beside my father, but, one by one, he placed the other dogs next to him and measured and felt and pullea at them. And each one he put down, but Be mever put my father dowa. He | And then he comes over and picks cried Miss | ay | up me and sets me back on the plat- form, shoulder to shoulder with the Champion Regent Royal, and S0oes down on his knees and looks into our eyes. The gentleman with my father, he laughs and says to the judge: “Think- Ing of keeping us here all day, John?" but the judge, he goes behind us and runs his hand down my side, and hoids back my ears and takes my Jaws between his fingers. The judge was looking solemn, and when he touches us he does it gentle, like he was patting us For a long time he kneels in the sawdust, loog- ing at my father and at me, and no one around the ring says nothing to nobody. Then the judge takes a breath and touches me sudden. “It's his™ he says, but he lays his hand just as quick on my father “I'm sorry,” says he. The gentleman holding my father cries 0 you mean to tell me—" And the judge, he answers, “T mean the other is the better dog.” He takes my father's head between his hands and looks down at him, most sorrowful. “The king is dead,” save he; “long live the king. Good-by, Regent,” he says. * x % % O that Is how I came by my “in- heritance,” as Miss Dorothy calis it, and Jjust for that, though 1T couldn’t feel where I was any différ- ent, the crowd ftollows me to my bench and pats me and coos At me. And the handiers have to hold ‘em back 80 that the gentlemen from the papers can make pictures of me, and Nolan walks mé up and down so proud, and the men shakes their heads and says, “He certainly is the true type, he is After that, if I could have asked for it, there was nothing I couldn't get. Miss Dorothy gives me an over- coat, cut very stylish like the cham- pions’, to weéar when we goes out carriage-driving. After the next show, where I takes three blue ribbons, four silver cups. two medals, and bring home $45 for Nolan, they gives me a “regis- tered” name, same as Jimmy's. Mise Dorothy wanted to call me “Regent Heir Apparent.” but 1 was that glad when Nolan says, “No, Kid don’t owe nothing to his father, only to you and hisself. So, if you please, Miss. we'll call him Wyndham Kid." But. oh, it was good they was so kind, for if they hadn't been 1'd néver have got the thing that was more to me than anything in the world. It came about one day whén we was out driving in the cart they calls the dogeart. Nolan was up behind, and me in my new overcost was sitting beside Miss Dorothy. I hears a dog calling loud for help, and 1 pricks up my ears and looks over the horse's head. In the road before us three big dogs was chasing a little, old lady dog. She had a string to her tail. where some boys had tied a can, and she was dirty with mud and ashes and torn most awful. She was too far done up to get away. but shé was making a fight for her life and dving game. All this I see in a wink, and I can’t stand it no longer and clears the wheel and lands in the road and makes a rush for the fighting. Behind me I hear Miss Dorothy cry, “They'll kill that old dog. Wait, take my whip. Beat them off her! The Kid can take care of himself,” and I hear Nolan fall into the road and the horse come to a 8top. The old lady dog was down and the three was eating her viclous, but as I come up. scattering the pebbles, she hears and she lifts her head, and my heart breaks open like some one had sunk his teeth in it. For. under the ashes and the dirt and the blood, I can see who it is, and 1L know that my mother has come back to me. I gives a vell that throws them three dogs off their legs. ‘ “Mother!” I erfes. “I'm the Kid.” I cries. “I'm coming to you, mother. I'm coming.” * % * % AND I shoots over her. at the throat of the big dog. and the other two, they sinks their teeth into that stylish overcoat and tears it off me, and that sets me free, and I lets them have it. Nolan was like a hen on a bank, shaking the butt of his whip, but not daring to cut in for fear of hitting me. “Stop it."K14,” he says, “stop it. Do you want to be all torn up?” says he. “Think of the Boston show next week.” says he. “Think of Chicago. Think of Danbury. Don't you néver want to be a champion?” How was I to think of all them places when I had three dogs to cut up at the same timé. But in a minute two of ‘em begs for mercy. and mother and me lete 'em run away. The big one, he ain’t able to run away. Then mother and me we dances and jumps and barks and lsughs, and we trots up the hill, side by side, with Nolan try- ing to catch me and Miss Dorothy laughing at him from the cart. “The Kid's made friends with the poor old dog.” says she. “Maybe he knew her long ago, when he-ran the streets himsel: ‘When we drives into the stables 1 takes mother to my kennel and tells her to go inside it and make herself at home. “Oh, but he won't let me:" says she. ‘Who won't let you? s 1 “Why, Wyndham Kid," says she. looking up at the name on my ken- nel. “But I'm Wyndham Kid!" says I “You!" cries mother. “You! Is my little Kid the great Wyndham Kid the dogs all talk about?” And at that she just drops down in the straw and ‘weeps bitter. ‘Well, Miss Dorothy, she satt1ed it. “If the Kid wants the poor old thing in the stables,” says she, “let her stay.” “Indeed, for me,” says Nolan, “she oan have the best there i{s. But what will Mr. Wyndham do?™ “He'll do what 1 say.” says Mi Dorothy, “and if 1 say she's to stay. she will stay, and 1 say—shes to stay And so we live In peace. mother sleeping all day in the sun or behind the stove in the head groom's office. being fed twice a day regular by No- lan and all the day by the other grooms most Irregular. And as for me, 1 go hurrying around the coun. try to the bench shows, winnin, money and cups for Nolan and taki; the blue ridbons away from father. Copyright. All rights resartéd.