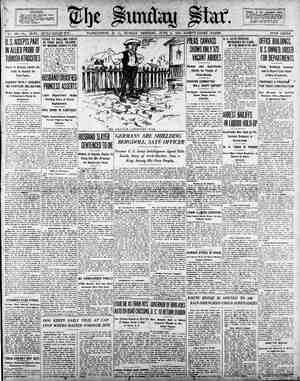

Evening Star Newspaper, June 4, 1922, Page 79

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

INVISIBLE COLOR BOOK' " e ——————p——2 LEARN TO DRAW So you can make little 'pigtureg of your own to paint And color like you have learned to do by painting the INVISIBLE pictures in thig beok. _Read carefully the following simvle instructions and you will quickly learn how to draw the objects your ART teacher has suggested h‘:fi' LESSON 11! Remembering that the A, B, C's of drawing are, A, the circle; B, the aquare, and C, the triangle, let us take just one of them today for our lesson: A, the circle, and see what ‘we can make with it alone. We have separated A into parts that are of different sized ‘circles and lines of different lengths. Notice in the pic- ture how you can draw many objects ‘with these same lines, without using ‘any of the parts of B and C. Try now to see in other objects around you the simple lines of A, B and C. Editor’s Note to Parents . This course of instruction for the¢ little ones is intended and plan to give them an understanding of, the few simple fundamental shapes that are used in the construction of all pictures, and to teach them to| look for these shapes in the objecta they are always trying to make pic.} tures of. Every child loves to dravi.& With an understanding of the A, B, C’s as outlined in these lessons, it will be very easy to teach them to draw well in a short time. The lesd sons will advance a little each weeld with an added interest to the child.! A serapbook kept of these lessons will be of value not only to, the " child, but many older and advanced, students. ~ . A GENTLEMAN OF-THE-ROAD By Hal Clifford ' HE day had been long and without interest for Charles Murray as he sat at the desk in the little telegraph office where his fathér was employed by the railroad as agent and operator. The station grew hot and stuffy to him as the afternoon advanced; Charles began to think about the ald swimmin' hole, where he knew most of the boys of his age would be. His duties around the office robbed him of many of the sports the other boys enjoyed. He had prac-' ticed sending and receiving on the instruments since he was a small boy and had learned much of the business connected with the office. At the age of 14 his father had come to depend upon him as an assistant. Often he would leave him in charge of the office to answer the call or report a passing trajn to the dia-; patcher while he went on some errand uptown. His father had just left the office on such an occasion, saying he would be' back in half an hour. Charles was tired now of trying to copy any more of what the instruments were saying; everything was going so fast it was difficult for him to write it down; some of the words he was unable to catch at all. The fellow in the gen- eral office was sending with a “wig-wag” and it required mere of an expert than Charles to catch every word. He hoped that some day he would be able to do it. He walked outside and sat down in the cool shade close to the open window where he could still hear the instruments and listen to what was going on over the wire. He had been sitting there but a short time when his attention iwas called to a man not far from the office, walking on the track, toward him. As the man approached Charles could see that his clothes were shabby and he was unshaven. “Another bum,” he said to himself, and paid no further attention until the man spoke to him and said: s “Hello, son, what place is this? Move over a little and allow a gentleman to sit down, will you? Why all the grouch on such a fine afternoon?” Charles moved o' r on the bench to give the man room, who continued with hig questions, askin; — A “Who is the ‘Ww.-talk” in the ‘wickie-up’? No one present, 1 see,” he said, glancing in at the window. “Isn’t that fine to have a boy like you who is respon- gible? Father can go away for an hour or so and everything is O. K. when he returns. You should be proud of the trust, m’ boy. While the other boys are off swimming or wasting their time playing you sit here growing into a useful, capable young man, who will take his place some day in the great industry of railroading. Do I make myself clear? Have you a match, please? Thank you.” When he had concluded Charles looked at him, wondering how it was that he could know about his father and that he was taking care of the office. Before he could ask the man continued. “You are asking me how do I know that your father is ‘wi-talk’—and that you are in charge of the office in his absence? Deduction, son—and experience— observation, as it were. One learns much by travel and thinking. You wish to know also the meaning of ‘wi-talk’ It is an Indian expression and means ‘wire- talk,’ used by them instead of operator or telegrapher. You have lost your il} bumor; 1 saw you smiling; that is good; you should learn to be happy; only old, disappointed men can be unhappy, and even they can learn to enjoy themselves #f they try. You thought when I came up that 1 was just a bum. Well, maybe 80, but 1 like to think that I am ‘A’ Gentleman of-the-Road.’ If 1 knew you better 1 might tell you who I a—"_ " “Wait!” Charles broke in, “the call,” he said, and hurriedly went into the office to answer it. He hesitated, wishing that his father was there to take the message. It was the General Office calling, and be knew that he would be unable to copy fast enough to keep up with that “wig-wag” instrument. He also knew that the fellow sending with it never slows up for anybody. He at last timidly, answered and tried to ask the operator to send slow, but he had no chance; the message started immediately, addressed to his father, and read “M. L. V. is on No. 3. Stopping there to take No. 2 back. Deliver following message. Impor- tant. Signed H. L. R.” Charles was only partly thru writing it when the operator tontinued with the important message. He had to stop him until he could finish with the first. This made the fellow very mad, and when he again started to send Charles knew that it was hopeless for him to try to copy that important message for the Superintendent—“M. L. V.” He opened the key repeatedly a'{d tried to tell the fellow to send slow so he could write it. .Each time made it tore difficult for Charles, until at last he was helpless and unable to make out ‘e word from the humming instrument as the words flew in. Again he was about ! 10 open the key to stop the message until his father ‘returried when the man had left on the bench outside leaned thru the window and said: *“Let him go son. Just tell him that you are in a.hurry and wish he would speed up a littl Tell him that and then listen to the music. He is a wonderful sender, I must say. - Charles hardly knew what to do now, but was prevailed upon by the man tel) the operator that he was in a hurry and to show a little speed. With thad he closed the key and listened. The instruments seemed to almost jump into a higher pitch as they hummed to the rapid clatter of a greater speed. Charles sat at the desk spellbound trying to catch the drift of the meutce.; He had| | never heard any one send like that before. His new friend smiled at hém and said. “How do you like it, son? Do you) "think any one could put that down? Huh! I used to know a young fellow who would go to sleep and write that fast on a typewriter 4nd never miss a word @ it. His name was Jose. I met him when I was traveling in India; very smar lad he was, one of the best in the wireless service during the war. We were together for two years in Paris. I wish he could hear this fellow send—it very fine work. He would enjoy the spacing and expression he uses. The sage is nearly finished; if you will make two copies of it I will dictate for There—he is done; give him the 0. K., son.” ¥ Charles could only wondler at such a performance of sending and receivin he had witnessed for the last five minutes. When he had his paper ready fo: two copies, by inserting a carbon paper, the man dictated the message word { !word as it had come from the wire. - The mon dictared the message word {or werd as # had come from the wird - ~ 'His father returned as they were finishing with the long telegram n’fl Charles told him of what had taken place in his absence. ; No. 3 pulled into the station a few minutes later and the luperintende:B ‘walked toward the‘office. Charles smiled and handed the important message him. ! His friend had disappeared around the corner of the station and was asleep, lying on the express truck in the shade. Charles was on the point going in search of him when the superintendent called to him. “Did you co this from that fellow in X’?” “No, sir,” replied Charles. “This is your writing, isn’t it?” he asked. ) L “Yes, sir,”%answered Charles, “but I did not take it from the wire. M_fl friend, ‘A Gentleman of-the-Road,’ received it and dictated for me.” The superintendent looked again at the message for a moment, then tul‘ned] to Charles. “A Gentleman of-the-Road, you say? Why, there is only one ma in the country that I know of who could copy and dictate from that man in ‘X, Where is he?” . ' A few minutes later the superintendent introduced Charles and his fa to the man who had helped the boy take the message. He said to them: "Mlog me to present my brother, I have been looking for him for five ysars to him the superintendent of telegraph of our road.” (The End)