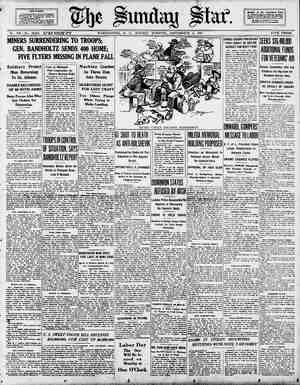

Evening Star Newspaper, September 4, 1921, Page 45

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

OU get very few things in this world unless you go after them. ventures as of any other de- This is as true of ad- sirable matter; and when a man is as bored by his existence as Morley Smith was, it is not strange that he should seek adventure. As he sat in his easy chalr at his c'ub—a most highly respectable and} gloomy club—his life seemed to him akout as tame and coloriess as pos- sible. He was close to fifty vears old, a bachelor. and with enough money to do what he wished. Something like eight yvears he had been sustained by an ambition. He lived at the club, finding that the most comfortable mode of life, and for eight years he had planned and mildly schemed to become the ten- ant of B.oom 45, room in the club. the air, so that one was not awak- For the most desirable It was high in By Ellis Parker Butler stories it contained. He was an ex- tremely deliberate reader. He often spent several months over & short popular novel, but the impressions made on him by what he read were for that reason tremendously deep. He inyariably declared that what he was reading was “beastly rot,” that being a safe attitude for criticism to take: but he was in no way com- petent to judge whether a book was trash or not, and he.accepted as deep philosophy some of the flossiest weavings of the most trivial fiction- ists. The short stories in the book he happened to pick up were neither trash nor trivial, although they were the most absolute fiction, and Morley Smith devoured them as thoroughly and as slowly as an inchworm de- vours a leaf. They were stories of adventure, true Arablan Nights, but the Bagdad was the city Morley Smith knew best— New York. It was as if the stories had thrown open a huge door that Morley Smith had not known existed. One walked through that door into a Tealm ot adventure such as Morley Smith_had not imagined possible in New York. Behind every door, the The Amater Aenturer' one who was accustomed to the duil elegance of wealthy town and coun- try houses. There was a atrong. warm odor of cooking foods, a min- gling of various dinmers, not pleas- ant to & man who had dined; yet it was not as unpleasant as might have been expected. The figured carpet on the stairs was worn to the warp on the edges of the treads. The cheap natural oak railings were in need of varnish, and the single gas jet flared at one corner. Morley Smith looked upward. Dimness and adventure were there! He mounted the stairs. He mounted slowly, s0 as not to lose his breath. As he neared the third floor. he saw more light, for a door was ajar; and as he raised his head to the level of the landing he saw a woman standing in the doorway, awaiting him. “Oh! excuse me!” she said, although she had done nothing to call for ex- cusing. “I thought it was Frank. The amateur adventurer was be- fore the door now. He removed his hat. “No,” he said. “My name Is Smith. I have a card here somewhere. May I come in?* 1 suppose you want to see HE, MORLEY SMITH, WAS ACTUALLY IN A STRANGE FLAT WHERE HE HAD NO BUSINESS TO BE. ened by early street noises; it was|author told Morley Smith, adventure flcoded by the morning sun in win ter; it overlooked the small roof- xarden next door, from which on pleasant evenings during the warm period very music sounded. Every resident member of the club coveted Roem 45 and made rlang ta cnm.n:e it when old Jason Birch gave it 4p! Every ome knew old Jason Birch would not give it up until he died. For eight years, therefore. Morley Smith had had a real object in life: but now Jason Birch was dead. and Morley Smith was domiciled in Room 45, and he felt that life- had temporarily lost its savor. When a man's one great ambition is achieved he feels lost. Morley Smith may be described. beginning at the ground, as the neatest shoes (which he called boots), the best-fitting spats and_the most beautiful trousers in New York. He was an ade at_saying “Oh! T say. old cha Once a month he looKed at his envelope of club checks and hoped the club book- keeper had totted the beastly things up correctly, what? Regularly once a month he took his pocket check- book and the bank's statement to the cashier of the Ancient National Bank and said: “Tot this up for me, old chap, will you? I can't make the beastly affair balance ‘There was always several thousand dollare balance to his credit; so it did not matter much whether it balanced or not. He did not spend all his time in the club. He knew many people. Fifth avenue and the adjacent streets were spotted with doors that gladly opened to him and he was continually being dragged to some elegant coun- try place on Long Island or else- where. He endured all this with proper resignation, but was tremen- dously bored by it all. The club bored him; life bored him. When the chappies began to come into the club wearing their khaki- colored uniforms his life bored him more than ever. They, lucky lads, were going to have a taste of what was doing. and they showed it in their faces and in their manner. They were brisk and business-lik aven in the club. They spoke audi- bly and as if they no longer feared the draperies. Morley Smith, sitting in the red-leather chair and saying, say, waiter, a brandy and soda, what?’ felt tremendously out of it He wished he was one of the lads and hooked up to this war thing somehow; and he would have been. but for certain infirmities that did not show on the surface. The men in the club were not all like Morley Smi There may. have been_a dozen more or less like him.. but he was the true fine flower of clubdom. He was a clubman. Every proper club has him, in varying num- bers. He does not know anything about anything worth knowing. He has a store of entirely incorrect in- formation, picked at random. * - hogs? Yes, I know them: the woolly beggars with the tails.” Or “Roumania? One of those little countries they carved out of Poland, you know. They keep their women in harems—what?’ For many years, being a clubman was a_ thor- oughly complete occupation. A man might be a banker or a poet or a clubman. It was a respected and re- spectable occupation. Suddenly, with the war. being a clubman became nothing at all. The banker began financing for the gov- ernment or selling bonds for the go: ernment. The poet began writing patriotism. For the genuine clubman there was nothing. You jolly well can’t be a professional clubman in a manner noticeably to assist the government. To sip a rickey and say, “I say! the Germans gre a rotten lot, what?" doesn't bite very deep when the younger chaps are actually wear- ing the khaki color and the banker member is just dropping in for a moment between momentous confer- ences having to do with billio of dollars or hundreds of thousands of tons. One gets pushed to one side and feels lonel. Morley Smith stood this he could. Once or twice he said to 2 banker member. “I say. old chap, if you see a chance to work me into this some way——" and was met with an “I'll_ remember it. Smith.” which weant Smith would be the last man 10 be asked to take part in tae big work on hand, and after standing on the edge of a group for a few min- ates with his glass in his hand, Mor- ley Smith would go back to the red easy chair and sip in silence. It became intolerable. His life seemed as colorless as a bit of water- soaked paper drifting aimlessly in a vast ocean. and It was while he was feeling thus that he picked yp a book erd to read ¢ short, ! waited for the coming of the ad- nturer, and he proved it by giving instances that became short stories of such interest that Morley Smith forgot to sip his drink as he read. Behind every door! You merely pick- ed out the door and tapped on it, and the- door. opened, and the adventure was there! *x % ]\IORLEY SMITH finished the book +'% and looked up at the famillar surroundings of the lounging-room of the club. A great city teeming with adventure, and he sitting here in this deadly, borsesome hole, dying of slow ennui! I say—what? He felt in his breast-pocket for his purse, opened it and assured himself that there were enough twenties among the smaller bills to see him through any reasonable adventure, replaced the purse and tapped the bell for a final drink. He drank with a sense of pleasant excitement, made sure he had a couple of clean handkerchiefs in his pocket (he never Frank? You are the insurance really! No, nothing _like Quite another matter, I a: sure you.” She took the card and read the name. ‘'Well, I expect Frank any min- ute” she said. “He ought to be here now. You can come kifo the parior and wait, if you want to. I'm getting dinner, and it will barn if I don't attend to jr.” She hurried ahead of him and lighted a gas jet in the paricr. It ‘was quite plebeian: furniture that pretended to be carved but that was really cut out of flat slabs—install- ment Stuff, very evidently—all cheap. It was beginning to show wear. too. The plush was going the inevitable way of all cheap plush. U going the way of all cheap rugri ‘That's the ‘most comfortable in a minu Sometimes he is a little lat> when he stops to buy something extra for supper—mean dinner. I'm from the west, and I never get over saying ‘supper.” Out there we had dinner went out without taking that precau- ; iR the mildle of the day. you know.” tion) and walked out to the coatroom. Arthur held the comfortable, fur- lined coat as Morley Smith siipped his arms Into it. He caressed the ten-dollar hat with a soft brush be- fore he handed it to Morley Smith with a “thank you” that was either In gratitude for the amount Morley Smith had entered against his name on the Christmas gratuity-sheet of the year before, or in gratitude for what Morley Smith was expected to sign this coming Christmas. To the doorman who opened the door of the taxicab standing before the club Morley Smith mentioried a street and number. ‘The street and number he had chosen at rando in the manner of true adventurers, and before they reached it he saw the driver scan- ning the house numbers. They drew up before a church. “I think this is it, driver doubtfully. Morley Smith looked at the church. sir,” said the | It was an entirely respectable and. sedate church, dark as to windows and evidently locked and barred as churches are for five nights in the week. “I say, you know,” said Morley s this east or west?” said Morl “It must have been west. ‘Try the same number west. my man. The driver wheeled the taxicab and bumped toward the west. When he had crossed 6th avenue he looked :ahc:mmtoh:hc cab as If wondering er his passenger wa: sober, but th it oo showed that Morley Smith was en- tirely sober. He was sitting erect, a plain, old-fashioned flat-building, one of a.long row. Morley Smith opened the door and stepped out. “Charge it to the club, Mr. Smith?" asked the driver, and the amateur |door. adventurer felt a comforting sense of safety as he heard the driver. If death lay at the end of this adven- ture, he would not have disappeared utterly. The driver would report. A fresh sense of caution came with this thought. “Ye: he saild. “And say, chauffeur! Come back for me in two hours, will you? I'm going in here”"—he pointed to the door of the flats—“and when I come out, I'll wait in the restaurant yonder. If I'm not there at 9 o'clock, tell the police, will you? Thanks. This is for you. The flat-building was divided In the middle by a hall. Morley Smith could see this through the panes of beveled glass in the doors. He pushed the doors open and entered. He found himself, on the street level, in a imall vestibule with walls tiled below and hideously decorated above, and set In the tiles were two rows of letter boxes, each with a push but- ton. In the small slots above the letter boxes were names. Some wers cut from visiting cards and some were written. Morley Smith examin- ed them all—Hirsch, Casey, Wildman and so on—and pushed the button below the box that proclaimed itself the temporary property of F. X. 'y. There was a mysterious click- Ing in the lock of the door that separated the vestibule from the hall, and Morley Smith opened the door while the clicking continued. He knew enough about fiats to know this 'was an invitation to enter. The-hall- was not: at.all-inviting 40! st | don’ lights from the lamps | « rant across as Moriey Smith looked & man came-out of the fone. Really!” said the adventurer. ‘Every one doés.” “You had better take off your co: or you will be cold when you go out. ‘Ah—may I ask what—ah—your husband’s occupation may be?" asked the amateur adventurer. He was really having quite a thrill of excitement. He, Morley Smith, was actually in a strange flat where he bad no business whatever to be, talking to a fair-faced young matrcn whose saucy eyes denied her sedate mn:anner, and the husband was iue at any minute. It is true that the was nothing in the young woman's manner to suggest that she feared her husband would rush into the flat in a drunken frensy and throttle her unless the visitor prevented him, but it was adventure none the less. Already Morley had learned that in the West dinner is called supper and is had In the middie of the day. I say, what? “Well, T guess maybe Frank had better tell you all that himself.” said Mrs. Casey, answering Morley Smith's last query. “I always think a woman should not mix into things like that. So just make yourself comfortabl Tl have to look after my dinner. She went as far as the door. "1l just close this door, 't min she said. “I'm cooking chops. and the smoke is something dreadful sometimes.” *x k VVEEN she had closed the daor and had retreated down the long elescope” hall to the kitchen the adventurer felt, for a moment or two, scanning the bulldings as they passed | that he was taking a silly risk. He by them. The taxicab stopped before [dropped his coat over the back of his chair, stood his stick against it, placed his hat on the floor and with cautious tread approached the clesed As quietly as possible he turned the knob. The door opened easily. He was not, as he had feared, locked in! As cautiously as before ke went back to his chair. - Even through the closed door he could hear a faint noise of spluttering chops. He heard the siss of them as Mrs. Casey turned them other side up in the pan. A faint odor of browning pork came through the door—possibly through the key- hole—and, although Morley had already eaten, his appetite leaped into new life. He had not eaten pork chops for y not for many By Jove, as soon as this ad- was_ended he would go somewhere and have a brace of pork chops! What? If+he was still alive, what As the adventurer sat there.in the commonplace little fiat parlor,- wait- ing for the real adventure to begin, he had nothing to do. He shook out one of the spotless handkerchiets and brushed a nose that did not need brushing. He removed one glove and folded it carefully. He looked at the shockingly bad pictures on the wall (installment-plan stuff) and then walk- ed to the window and looked out. Here and there across the way were lights in the windows, but most of the windows were black, the families being in their dining’ rooms.. He looked down and saw, a policeman standing under a lamppost slapping his arms across his chest. The it- spot in the street was the the way, restaurant carrying two or three pa T bags. As he closed the door ind him. the man looked up to the very window where Moriey Smith stood and waved a d. ‘The adventurer stepped back and moved softly to his chair. Buddenly he had an overwhelming feeling that he was not at all' an_adwventurer probing the mysteries of a modern Bagdad, but a sflly and reasanless in. truder into the privacy of a very or. dinary home. He felt, at that mo- ment and for a cousiderable time mf- and an ordinary young hu bring- ing home additional provender in pa- per bags, and he, Morley Smith, sit- ting in the parior without the stght- est_excuse to glve the hwsband for being Morley Smith felt deeply-and pain- fully the differemce between ‘the sort of chaps an author -cldr[toh adven- tures and himself. of ‘those chaps would have a lot of things to-way. don't yeu know! The things the chap would say would make /. all right— make an advemture of it. Morley Smith realised suddenly ‘that, by Jove, he didn’t have & thing to say, what? This chapple would come up the stairs and open the d-sor and see him and say, “Well, what is 1t?" and Mor- ley Smith would not know what it was, or how to say It was mot any- thing. He would luok a perfect fool, what? silly busines: He heard the be,) ring In the kitch- en in answer to ‘the husband’s touc on the button bedow, and he imagine the answering <lick in the lock of the entrance dcor downstairs. He walked to the -door that led to the outer hall. It was locked! He might have escaped that way. He heard Mrs. Casey w Alking to the other door -—the door f'som the marrow hall into lthe outer Fall—and he fled back to his_chair. Hello, Tpots!” he heard the hus- band 1/ the wife. “Late, but I bring you something. How's her kid- lets?” He hesrd the kiss. “I sm ¢}l something good!" he heard the hu gband say, and then he did not quite aear what the wife said. but he knew It was warning that a man was in t'je parlor. “That so?" said the husl/ind. “Take these packages, will yor Tdrs. Casey opened the parlor door. “This is my husband, Mr. Casey,” she +aid. “This is his card, Frank. Il 4ot _you men be" ing out his hand. with just a guick gl’:nce at the card. Morley Smith took the hand, and as Mr. Casey walked to a chair e noticed that the {young fellow limped and that he limped badly. He had not noticed that he limped as he came out of the restaurant. For & moment or two the young man looked at Mr. Morley Smith, and they were miserable mo- ments. “Well?" said Mr. Casey His eyes had, Morley Smith saw, become hard and suspicious. There was nothing of the lightness and care-free badinage with which he had greeted his wife in the young man's manner now. He was stern, keen and alert. Tne adventurer eyed him crit- ically. If the young fellow became angry it would be an even match, he figured. The young man looked hard of muscle, and he would be guick, but Morley Smith had weight:and he was not altogether out of training. “All right—say. it!" said Mr. Casey. The adventurer, as he had feared, had nothing at all to say. It oc- curred to him to say that it was pe- culiar—what?—to call dinner supper in the west, but the remark seemed inane under the circumstances, and he did not say it. “I suppose you are from the in- surance company,” said Mr. Casey, seeing that the stranger meant to say nothing. With all his heart Morely Smith wished he was. He wished he could say he was. He regretted that he had not flatly denied to Mrs. Casey that he was from the insurance com- He felt, more than ever, that not cut out to be a modern venturer. A writer-chap would ve said to Mrs. Casey, “That may be, or that may not be” or some- thing of the sort, don't you see? A writer-chap would have been up to th not from an in- said the adven- Mr. Casey seemed disappointed. “You're not from the-car company, are you?” he asked, as if this was a new idea and one he had not pre- viously entertained. It was Morley Smith’s opportunity. “That may be. or that may not be,” he sald non-commitally. ‘'Well, you ought to know." said Mr. Casey with a slight laugh. *I don’t if you don't He became more gracioys. He be- came actually friendly. 5 “1 may as well tell you right now,’ that there is nothing to see on my leg.” 2 said Morley Smith. He began to feel on safer ground. For some unknown reason the young Mr. Casey and he seemed to be changing places. He felt it. Instead of being reserved and suspicious, the young man was becoming friendly and open. “There may be a little black-and- blue left,” said Mr. Casey, “but you can’t expect a bruise to show for- ever. Quite s0!" said Morle That would be monsense, whatr: ‘Anyway, if you wanted to see the bruises, you ought to have come sooner,” said Mr. Casey. ‘The insur. ance doctor saw them all right. And this limp it gave me—I don't know when 1 will get rid of this limp.” 2 " sald i ot nowing whaioid, Horley Smicn. you don’t need to come any SF Jthat!” said Mr. Casey angrily. nt daiming you lamed me for life, or anything like that, but T've Bot case enough to Sue on and to get big damages. too. Any fury— and a street car corporation’ don't stand half a chance. I mean, a man gets his rights from a fury— My good man,” Morley Smith heg:fl rather patronizingly. 2 - ght, then.” said Mr. Case hotly, “I'll sue! 1 thought you had come up here to settle this business like one man with another, and was ready to do the fai; o Tont r thing with e stopped short. In makin, movement. Morley Smith had dia: arranged his coat so that the luxuri- ur lining was exposed, Casey's eye dwelt on it F “Now mow who you are!" sald angrily. “I call it sneaky, I ;‘: coming up here this way. Well, I've BOL your mame now, and my wit. neases will know you whem I get you into court. They'll Wentify you, easy enough. One—two of = them said you were driving that man- killer auto of yours the way no man ought to drive. They'll say that in court for me. When your car knocked me in front of the street car— of thai *x MR. CASEY stopped short again. There was a blank look on -the face of his visitor. As a matter of fact, the adventurer was trying to plece things together, to leave some sort of sense out of the tangle of words Mr. Casey had thrown at him. For a minute he had felt safe—Casey thought he had come to adjust some claim Casey had against a trolley company. Now the adventurer was all at sea again. His brain would not cope with this new complication. He was willing to some one— any one—if he could get out of this man's flat without weeming ridic- ulous, but man would not let him be any one for more than a mintte at & time., Then he wanted him to be some one else. Mr. Casey, on his side, saw the mystification on Morley Smith's face. He hesitated. He was worrled. He could not de- cide whether Morley Smith_had come to settle for the trolley company or to settle as the owner of the auto- mobile. He had not expected either. In his heart he knew he had had no business to be ing the street in the middle of tie block. The auto- mobile’s fender had twr.a him and had sent him into the fender of the rolled him | ash 1sed— he saw this wll fed. well . e Thhis oarior ho Bad 2ot thongnt I say, you, know, it was a | h d | The young husband advanced, hold- | Il with relief. “I sa; ! might be thrilling, but Morley Smi begi A THE MIRRORS OF DOWNING STREET" * » SOME POLITICAL REFLECTIONS BY “A GENTLEMAN WITH A DUSTER.” ted by @. P. Putsam's Sons. ' s .fl"llm".ud.l Feature 8y An (The Right Honorable Devid Lioyd u Manoneotor, 1508: on of the Jate Willlam George, v of the 8 Usitarian Schools, Ed a Welsh 1916; Prime Minister, 1916-20.. i F you think about It, no one since . Napoleon has appeared on the earth who attracts so universal an interest as Lloyd George. This is a rather startling thought. It is significant, I think, how com- pletely a politiclan should over- hadow all the great soldiers and ailors charged with their nation’s | very life in the severest and infinitely ithe most critical military struggle of man’s history. A democratic age, lacking In color {and antipathetic to romance, some- jwhat obscures for us the pictoial |achievement of this remarkable fig. iure. He lacks only a crown, a robe {and a gilded chair easily to outshine iin visible picturesqueness the great ‘emperor. His achievement, when we {consider what hung upon it, s great- | ;er than Napoleol the narrative of his origin more romantic, his char- acter more complex. And yet, who idoes not feel the greatness of Na- poleon?—and who does nmot suspect the shallowness of Lioyd George? History, it is certain, will unmask his pretentions to grandeur with a irough, perhaps with an angry hand but all the more because of this un masking posterity will continue to crowd sbout the exposed hero ask- ing, and perhaps for centuries con- tinuing to ask, questions concrening his place in the history of the world. How came it, man of straw, that In Armegeddon there was none great- er than you?” * *x ¥ ¥ T HE coldest-blooded among us must confess that it was a moment rich in the emotion which bestows immortality on Incident when this son of a village schoolmaster, who grew up in a shoemaker's shop and whose boylsh games were played in the street of a Welsh hamlet remote from ail the refinements of civiliza- tion and all the clangors of indus- trialism, announced to a hml.leu[ Europe without any pomposity of phrase and with but a brief and con- temptuous gesture of dismissal the passing away from the world's stage ©of the Hapsburgs and Hohenzollerns —those ancient, long glorious. and most puissant houses whose history for an aeon was the history of Eu. rope. How is that this politicia; attained to such super-promigencer” Another incident helps one, I thi to_answer this question. Eariy 1y the struggle to get muniti, British soldiers a Mmeeting oforll.?l l'g: principal manufacturers of ments was hald in “'hllehlll-r"!::h the object of per their (rade secrers o7& them to pool For a long time this meeting ‘was more than a lnt.‘catll‘on of espomaibis o sible workpeople and lhlrellolllel'l“’fo:hteh‘: tp:zl.:::“’;oo'b:"'u competing under- . impracti fakIaws ol practicable if not At a moment wi manufacturers, hen the proposa the government ssemed’ Tonr My Lioyd George leaned forwar. chalr, very bale, very qulet snd very earnos “Gentlemen," he said in a voice that uced an extraordinary hush, “have you forgotten that your sons. at this very moment, are being killed —killed in hundreds and thousands? They are being killed by German guns for ‘want of British guns They are being wiped out of life in thousands! Gentlemen, give me guns. Don’t think of your trade secrets. Think of your chiidren. Help them! Give me those guns.” This was no stage acting. broke, his eyes filled with tears and his hand, holding a piece of note- paper before him, shook like a leaf. His voice In being assured that the insurance company would allow him twenty-five dollars for the time he had remained at home. Now he moistened his lips and started at Morley Smith, trying to_decide what to say next. Mr. Casey felt that he must be care- ful. If he laid the blame for his acci- dent on the car company. and this man was the owner of the automo- i bile, he would get nothing: if the man was an adjuster for the car company and Casey laid the blame on the auto- mobile, he would get nothing. He felt it would be too raw to ask the man who he was and then base his claim accordingly. At that moment Mrs. came to the parlor door. “I'm sorry, Frank,” she maid, “but if you walit another minute the chops will be dried to chips. If Mr—Mr. Smith will excuse you—or maybe he will have just something with * “Do, won't you?" urged Mr. Casey y!” said Morley Smith. *This 't it, eat- is going it a bit strong, Is ing_your dinner for you?” “Oh, we would be pleased,” Mrs. Casey. “Sure! If you don’t mind taking what we've got.” said Mr. 5 Morley Bmith felt a new thrill of exultation. The adventure was ad- venturing after all' Why, by Jove, he was get along of those writer-chips woul have: got along! I say, what? That book- fellow was all right, what? As he ate his dinner (and _the chops were not dried to chips), Mor- iey Smith felt that the adventure was better than an extra dividend. He would not have missed the ad- venture for & thousand dollars. A bit of class, coming into a chap's home and being fed and all that, when nobody kmew him from Adam! The adventure was not, to be sure, a: thrilling as some he had read in the book, t he was glad it was not. Later adveatures. on other evenings. said was satisfied to n thus and work up to murder, abduction and the rest. Mrs. Casey 'was a nice little hostess, She talked _enor but she talked more of her husband than of other 008, at & bIE | ¢ho rnnin ne reason he birthday had come around and he had hurried across the street to buy a set of furs he had seen in a window— muff and stole, fifteen dollars com- lete. 7 x “They were just elegant!” she sald ‘enthusiastically. saw them my- self.” 1" exclaimed Mr. “Fifteen dollars, His coat had cost eight hun “Well, Frank oould afford It Fant asnand | Wers not quite pan: nt “We're not qu! - ::n » birthday only eomes once a yea; “Really!” sald th he felt he Birthdays do & year, you know. amed. what? h then silly. j LLOYD GEORGE. —_——— The trade secrets were pooled. The supply of munitions was hastened. 1Y This is the secret of his power. man of our period, when he is pro- foundly moved and when he permits his genuine emotion away, can utter to carry him an appeal mefence with anything like so compell- ing & simplicity. His failure lies in| “That is the life of the poo: a growing tendency to discard an in- stinetive emotionalist for a calculated astuteness which too often attempts to hide its cunning under the garb of honest sentiment. His intuitions are unrivaled: his reasoning powers in- considerable. V =% % * HEN Lloyd George first came to! _ London he shared not onmly &l room in Gray's Inn, but the one bed! that garret contalned with a fellow countryman. They were both incon- veniently poor, but Lioyd George, the poorer in this. that as a member of parliament greater. The fellow-lodger, who aft- erward became -private secretary to} one of Lloyd George's rivals, has told | me that no public speech of Lloyd his, expenses were the George ever equaled in pathos and power the speeches which the Young|ism of member of parliament would often{were disordered and crude; neverthe- | hungry days. seated.on |less . the spirit that make in thos the edge of the bad ‘or pacing to aidiwas to con-| There was not a man who heard him | encouragements whose humanity was not®quickened. in the imporgant years of boyhood. The story was the story of his idowed mother amd of her hero No | struggle, keeping house for her shoe- making brother-in-law on the little money earned by the old bachelor's village cobbling, to save sixpence a week—sixpence to be gratefully re- turned to him on Saturday night. he ex- claimed earnest Then he added with bitterness, “And when'I try to give them five shilling a_week in their old age I am called the ‘cad of the cabinet Nothing in his life is finer than the struggle he waged with the Ifberal cabinet during his davs as chancellor of the exchequer. The private oppo- tion he encountered in Downing street, the hatred and contempt of some of his liberal colleagues. was exceeded on the other side of politics only in the violent mind of Sir Ed- ward Carson. Even the gentle John Morley wag troubled by his hot in- sistences. “I had better go.” he sa‘d to Lioyd George, "I am getting old 1 have nothing now for you but criti- cism.” To which the other replied, “Lord Morley, I would sooner have your criticism than the praise of any man living"—a perfectly sincere remark, sincere, 1 mean. with the emotional- the moment. His schemes informed them dike:a ‘mew birth in the politics fro in the room, speeches lit hy onelog the: wirdle world. A friend of mine passion of justice and directed to cn-{ f great object; lit by the passion of justice, directed to the liberation of all peoples oppressed by every form of_tyranny. This spirit of the intuitional re-|tg former, who feels cruelty and wrong like & pain in his own blood. is stilltion about the hills of present in Lloyd George, but it is no longer the central passion of his life. It is. rather, an aside; as it were, a'He has ceased to be a prophet that revives on memory hours. On several occasions he hasij in leisure spoRen to me of the sorrows and suf- ferings of humanity with an unmis- takable sympathy. I remember was a moving narrative, for never once did he refer to his own personal charl e look band, his “Yes? “You parlor, that! . nevs s ow: One of the paper bags had contained otte russe. say!” he Do away er once express re- n loss of powerful said suddenly. He ed from Mrs. Casey to her hus- eyes bright with a big idea. queried Mr. Casey. were going on a settling with me. you know Y. bit about Back there in the Cracking idea. h suits and juries and all that sort of thing, what? Beast- ly nuisances, the lawyer chaps. Sup- pose 1 buy the lady a birthday pres- ent, what? You know what I mean, old chap—let you buy it, and all that. What say we settle up the damages right tle. 0 thing—" he He stopped. visitor nine, now?" He drew his purse from his inside pocket and placed it on the table. Mr. Casey moved his chair back a lit- w, I'm willl ten’ n. From the purse his taking bills—one, two, three—six, Morley Smith ing to do the fair twenty-dollar seven, eight, felt in the purse, but there were no more twen- He slid the pile to Mr. Casey.! “What say?’ he asked. ties. Mr. fore twen Casey woul ty-five ld have fought be- he would have accepted less than dollars. ought to be worth that. accident took the A\u‘{a two hundred dollars in his hand. *Fair and liberal, I call it—dont as well a5 one | you, Toots' “Bu t we can't that for furs in 1y. asked Casey. tottering along. Jolly nice had.’ you, Morl hi bit of it, though” he said firm- “You'll see “We're ever so much obliged to said Mrs. her hand. Yes, thanks,” said Casey, and he shook hands warmly., ‘The amateur into the hall an and out into the crisp, cool He felt uplifted, his taxicab waiting and_hailed and drove to th and hugged it she cried. “Two dol 3 folded the bills and handed them her. “It's yours, kid,” he said. bellave mel™ “What?”" “That's one guy that won't hold Morley ‘l‘!‘: l’h.lh 1ease. the al over. ey Smith put his purse back pocket, buttoned his coat and “Well, thanki possibly spend all to that, what?” he be ime T've Casey, giving him in!amusing adventure, he has retah {amus : ned particular one occasion on which he!littie of his original genius except its Penstock and dam, told me the story of his bovhood; i | I | i told me that he had seen pictures of Lloyd George on the walls of peas. ants’ houses in the remotest villages of Russia. But those days have departed and ken with them the fire of Lioyd George's passion. The labored perora- f his ancestors, repeated to the piont of the ridiculou is all now left to that fervid period. Sur- ounded by second-rate people, choos- ng for his intimate friends mainly rich, and now ¢horoughly liking the game of politics for its it quickness. * * ¥ % 1S intuitions are amaziag. He as. tonished great soldiers in the war by his premonstrations. Lord Milner, a cool critic, would sit by the sofa of'the dying Dr. Jameson telling how Lioyd George was right again and again when all the docidiers were wrong. Lord Rhondda, who disliked him greatly and rather despised him, told me how often Lloyd George put heart into a cabinet that was really trembling on the edge of despair. It seems true that he never once doubted ultimate victory, and, what is more remarkable, never once failed to read the German's min I think that the doom that has fallen upon him comes in some measure from ! the amusement he takes in his mental quickness, and the reliance he is some- times apt to place in it. A quick mind may easily disorderly mind. More- jover, quickness is not one of the great qualities. 1t is, indeed, seldom a pari- rer with virtue. Morality appears on the whole to get along better with- out it. When we consider what Lloyd George might have done with the fortunes of humanity we are able to see how great is his distance from the heights of moral grandeur. He entered the war with genuine pas- sion. He swept thousands of hestitat- ing minds into those dreadful furnaces by the force of that passion. From the first no man in the worid sounded so ringing a trumpet note moral indig- nation and moral aspiration. ~Examine his earlier speechés and in all of them Fou will Snd that his pamsion to de- dations of morality and was Peace with a sword. Germany had not so much attempted to drag mankind back to barbarism as opened a gate through which mankind might march to_the promised land. This was in 1914. But soon after the great struggle had begun the note changed. Hatred of Germany and fear for our allies’ steadfastness oc- cupled the foremost place in his mind. [venturer went out|Victory was the objective and his down the stairs night. He saw it He had had ing of his life. danced around Frank X. Casey elated. club. “But, long! I oan ®ee his finish. 0t even ask me to can see » gaia |in & mu“u got sign a re- him trotting back me to sign before You watch!™ randy | bad "l‘l._rnnt ‘:t 1@ m'ln.': |l Mr. o Botng o let hars G was_Supremely and blessedly : content- with himself and the clul ghrht-n. Just the sam T get e e i 3 ey Bmith toyed with his ‘fork. | ventures, * | definition of victory was borrowed from the prize ring. A better world had to wait. He became more and more reckless. There was a time when his indignation against Lord Kitchener was almost uncontroliable. For Mr. Asquith he never entertained this violent feeling, but gradually lost patience with him, and only decided that he must go when procrastination St to jeopardize “a knockout ow. Any one who questioned the cost of the war was a timid soul. What did it matter what the war cost so long as victory was won? Any one who questioned the utter reckiessness ‘which characterized the ministry of mu- ritions was a mere fault finder. And the end of it was the humili of the general election of 1918. ‘Where was the new world :hen? He ‘was conscious only of Lord North- cliffe’s menace. Germany must pay and the kaiser must be tried! There was no trumpet note since. The truth is that Lloyd George has gradually lost in the world of polit- fcal makeshift his original enthusi- asm for righteousness. He is not a man to the exclusion of good- exclusion of badness. pure and impure; good and wonderful and common- place; in a word, he is everything.” * * % % DETECT in Lloyd George an in- creasing lethargy, both of mind and body. His passion for the plat- form, which was opce more fo him than anything else, has almost gone He enjoys well enough a fight when he is in it, but to get him into a fight is not now o _easy as his hangers-on ould wisl The great man is tired, and, after all, evolution is not to be hurried. He loves his armchair, and he loves talking. Nothing pleases him for a longer spell than desultory conversation with some one who is content to listen, or with some one who brings news of electoral chancey Of_cor his fati mounts ree, he is e tired man, ue is not only physical. ) up in youth with wings like an eagle, in manhood he was able to run without weariness, but the first years of age find him unable to walk without faintness—the supreme itest of character. If he had been able to keep the wings of his youth I think he might have been almost the greatest man of British histor: But luxury has invaded, and cynicism, and now a cigar in the depths of an y chair. with Miss Megan Llovd rge on his arm, and a clever poli- j tician on the opposite side of his hearth, this is pleasanter than any poetic vaporings about the millen- nium. > One scems to see in him an illus- trious example both of the value and perils of emotionalism. Before the war he did much to quicken the so- cial conscience through the worl at the outbreak of war he was the very voice of moral indignation; and during the war he was the spirit of victory; for all this, great is our debt fo him. But he took upon his shoulders a responsibility which was nothing less than the future of civil- ization, and here he trusted not 1o vision and conscience, but to com- promise, makeshift, patches; and the future of civiligation is still dark, in- deed. This, I hope, may be said on his be- haif when he stands at the bar of his- tory, that the cause of his failure to ! serve the world as he might have done, as Gladstone surely would have done, was due rather to a vulgarily of mind, for which he was not wholly responsible. than to any deliberale choice of a cynical partnership wiin the powers of darkness. Trapping Eels. "THE eel is like the salmon in ita life habits. Both are salt-water fish jwhich migrate annually from the ocean to fresh water. and return later to the sea. The motive of thiz migration is dif- ferent. however. The salmon comes from the oceam to spawn, and (h» young fry are reared in fresh water The eel goes to the sea to spawn and rear its young, and return, often hun- dreds of miles, to the muddy bottoms of fresh-water ponds and streams 10 grow and get fat. So eels are always best with us in the Jate autumn, at the time of their return to the sea. A certain river in Maine has its headwaters in a chain of twenty-four muddy lakes and small ponds, and the number of eels which travel through it. spring and autumn, enormou At 4 dam where an iron “penstoc was newly placed to lead the water down to a turbine wheel, a strange ccident happened. { The penstock is five feet in diam- | eter, two hundred feet long, and falls | ifty-two feet, and when autumn came ! the eels tried to pars through it. Such were their numbess that the 400- horsepower tdrbine was choked and topped by their bodies. A day of #d work:was required o clear the but He | | H i st i The “and ‘Penstock and wire | netting of course interfered with the migration of the eéls of those ponds iand streams. This, howeve: ! appeared . o ynderstand | tarmers, who Tiked _t barrel of eels for winter, went on setting eel-pots on the wrong side of the dam, just as before, for they sup- posed that an eel lives in the mud at one particular spot all its life long. T HAT summer & naturalist. who had heard the story. came to see the and while looking {about he explained the migrations of eels to one of the boys there. Now, many boys would have for- ! gotten it all by the next day; but this !lad was bright enough to concluds that if eels were all going one way at one particular time, then would be a . good time to catch them. i” He ana two- other lads put their ! heads together and late in October ! they attached a strip of wire netting two feet high along the whole top | of the dam and made It fast at both | ends. When, after the autumn rains, water overflowed the dam. it ra through the nettmg., but the eel could not pass. They had 1o g0 to a | point near the south end of the dam. Where the boys had folded the netting into a kind of tunnel, with an ori- fice four inches in diameter at the down-stream end. Now, to this orifice the boys had attached a piece of old fire hose. twelve feet long. and had rum the other end into &_hogshead at the foot of the dam. They bored auger holes in the staves of the hogshead to let_out the water. This eel trap, founded on actual knowledge of the life habits of eel. was an immense success, for eels in great numbers on their way seaward came nosing along the netting. and, finding only one way out, landed in the hogshead below. One might. fol- lowing a heavy rainstorm, the boys found the hogshead full of eel During. the next five nights they caught nearly fourteen barrels of eels, which they sold on the spot for three dollars a barrel. Jumping Stars. NE of the most interesting things appearing in the telescope when that instrument is pointing heaven- ward is the appearance of jumping stars. Of course, we can see stars twinkle without a telescope, but with a telescope they may seem to jump and actually to dance. The cause is the same—mixing currents of light and heavy alr causing refraction or bending of the rays of light coming from the star. We can see the same phenomenon by looking at a small object in & room through the air di- rectly over a hot radiator. The ob- Ject seems to p and dance, as if playing hide and seek with itself. This jumping in the telescope or twinkli: to the naked eye has also been explained by what is called in- terference, If two sources of light re placed close to each other, then on a screen placed properly we can catch an alternate band of white and dark lines. Of course, if the eye be placed at a dark line it can see neither source of light. .The pro- duction of these dark lines is accom- plished by different light waves reach- ing the screen In opposite phases so as to blot out or cancel the effect due to each. In like manner it can be shown that if the star has polychro- matic light, it can, and has actually been observed to, change color from this effect alone. ‘The best time to observe this effect of star dancing Is on a cold, crisp night. The telescope should be pointed to & twinkling star as near the hori- =on as can be found, as to see a slar &n” :I‘eh a-m we thlv. .‘m rm much more atmosphere to see one in the zenith, and there is. chance for vari