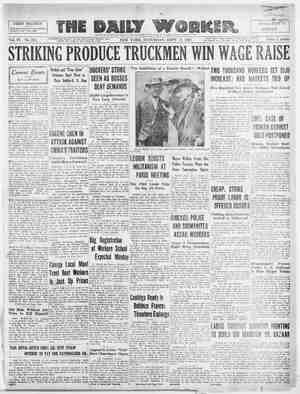

The Daily Worker Newspaper, September 17, 1927, Page 9

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

tt The Fourth Tower OU say that your epoch is heroic, that our time has passed, that we are no longer capable, are worn out, that our time was not, after all, interes- ting; but I will tell you, young people, that every epoch was heroic, people always knew how to die stoically, not only for an idea, but sometimes just like that. If it wouldn’t bore you, I can tell you of just such an episode. By trade I am a painter, and can even make pictures. Of course one must know how to make pictures, there are even places, they say, where that trade is taught, but I, with my fifty years, what had I to do with places of learning? It was in 1905, that year of liberty, when our party group aled to me. “Michael Vanitch, please paint the party slogans on a red banner, but make the letters in gilt, please.” Of course I did my best. On the black banner I painted in Slavonic letters, in silver, “Eternal Memory to Those who Fell in Freedom’s Cause.” On the red one, I painted in gilt, “Long Live the Democratic Republic, Long Live the Social De- mocratic Labor Party of Russia, Proletariat of all Countries Unite!” The Bolsheviks in those days, - don’t let it peeve you, my young people, were all for the democratic republic. With these banners, we all went out to. make a demonstration against the Black Hundreds. We were about thirty, with sticks and pikes and revolvers, that wouldn’t shoot a cat—to say nothing of a man,. especially if his coat were lined. Well, we marched about with the red and black banners and once the Black Hundreds surrounded us and nearly threw all our fine fellows over a precipice. They had about three thousand and we, as I said before, were about thirty. Well, we came out of it with honors; some forged ahead, while the others raised their sticks like spears, and the Black Hundreds were frightened. They divided and let us march through. That same day we hid the banners in a safe place and soon the police began to catch us—raid after raid, arrest after arrest. They came to me too, turned every- thing upside down, even chopped up the potatoes in the cellar with their swords. Then they pulled off the rag mats which my wife had spread, to rip up the floor, I suppose, and jumped with satisfac- tion. The banners, my young people, I had painted in my cottage, on the bare floor, and the paint soaked right through the satin and stuck to the boards. “Long Live the Democratic Republic”, was painted in gilt, lengthwise across the floor, and crosswise, in large silver letters. “Eternal Memory to Those who Fell in Freedom’s Cause”, “Here,” said the sheriff joyfully, “this is the headquarters of the most important socialists. There it is, word for word like the banners. What more can we want? The governor will praise us. Come on, now, get ready!” Well, I got ready and we went, for such a long time as makes me sick to think of. The trial was eight months Tater and then I was sentenced to four years and sent to the first annex of the provincial prison. I 7 * * From the investigation cell I was transferred to the common one, where I received better treatment. This gladdened me, like a breath of freedom. The others in the common cell were all fine fellows, sociable and educated. They started working on me at once. There I first learnt Marx’s theory and Frederick Engels’, as much of course, as I could, with my brain. We had all kinds of arguments, almost fights sometimes, especially with the Social Revolutionists. The mensheviks usually replied (A Story; with sneakiness and silence. The bolsheviks would get them into a corner and they would just stand there, neither yes nor no, or with a contemptuous smile say, “O, they are all demagogues, idiots, boneheads” and so on. But such irresponsible dec- larations didn’t affect the bolsheviks.. However, I didn’t get much time to learn political sciences as the governor of the prison found out that I was a qualified painter and in addition, could make pic- tures, so he sent me out to work—to decorate his house with painted designs. I did it well; he praised me but didn’t pay anything. He showed off to visitors, boasting what sort of convicts he had, regular. painters and artists. Now, at that time I got a money order for five roubles, I didn’t know from whom and was dreadfully astonished. My wife, I thought, or the party had sent it. “Well,” I thought, “let’s have a celebration. I'll treat the whole cell,” and so I wrote a note of hand and a large order and sent them to the governor. But it turned out differently — In the evening, that same day, they brought the order — biscuits, tobacco, tea, sugar, and even sausage. Here it entered my mind to look at the back of my money order. over! The money order wasn’t for me at all. Every- thing was right, my full name given and family, but the feminine signature and handwriting was not right. My wife’s name is Katerina and the one signed’ was Avdotia and there were all kinds of tender words there and talk of affairs not cor- responding to mine at all. Well, we gathered up the whole order, packed it and sent it back to the prison office. “Received this by mistake, beg you to find the rightful owner and give him the whole order. We enclose the stub of the money order.” We sent the order away, talked a little, saying that I was in too much of a hurry to make the order —perhaps the owner didn’t want those things at all —and then forgot all about it. Life is full of mis- takes. As soon as we finished forgetting about it, the governor’s assistant, Storky he was nicknamed, burst into the cell. He was long and spare, with a yellowish color and a loag thin beard, crvel as the devil and considered &ll the convicts his slaves, worse than cattle. Well, he burst into the cell and rushed straight at me. “What’s this, you son of a gun, cheating, are you? What right have you to take other people’s money?” “T didn’t take anything, sir, it was a mistake.” “Silence! I will flog such scoundrels .. .’ My head swam. around and my face burned. I said to him, hoarsely, “T am unarmed and can’t kill you, dog, so take this,” and I spat right into his face. Storky dived into his pocket and pulled out a gun, waved it in my face, but didn’t shoot — he was a great coward—poked about with it, stuttered and spluttered and flew out, with my spittle in his thin beard. In an hour, the lock. rattled again, the jailer came in and said to me, “Come, on, you’re wanted in the office.” Well, to the office I went, the warden behind me and after him the convoy. The political cell hums with indignation: “Don’t flinch, Michael Vanitch, we'll stick up for you, declare a hunger strike, start a fuss, call the attorney-—don’t flinch.” And I don’t flinch. I am desperate and burning with indignation. The governor is sitting in his office, bent over some papers. He did not even stir when I entered. THE HORNET’S NEST. I looked and almost fell - (Translated from the Russian oF G. Ustinov By VERA and VIOLET MITKOVSKY.) We stand, I just inside the room, the warden in the doorway. We stand ten minutes, fifteen. The governor keeps on sorting his papers and doesn’t even raise his head. I clear my throat. It is tiresome to stand still. The governor starts on a new packet of papers. I clear my throat again. The governor pretends he has no time to spend on bagatelles while important work remains unfinished, so we stand there for another fifteen minutes. I clear my throat, cough, even blow my nose five times, but the governor is absorbed in his papers. x Then he raised his eyes to me. “Well,” he said reproachfully, “what done now you numbskull?” He shrugged his shoulders helplessly and sank back into his work. “IT can’t save you,” eyes off his papers. “JT haven’t asked you to do so, sir.” Silence. In about five minutes the governor made a gesture with his hands as if he wanted the guard to leave. The guard went out and we keep still again, I by the door and the governor at his papers. “Well,” he repeated, “do you know that if the matter should come to trial that—” and he passed his fingers across his neck very expressively. “Oh well,” I said, “first he calls me a scoundrel and now you want fo hang me.” The governor covered his face with a paper, as if reading it very carefully. Then he suddenly threw it down on the table and said, “Storky will never forgive you and I can’t make him. I will punish you myself and he, as my sub- ordinate, may consent.” I stand still near the door and the governor stares out the window and chews his pencil. Suddenly he turns to me. ‘Do you want to go to the fourth tower for six months? If not, it’s the trial.” The fourth tower! It hangs as a curse over the whole prison, the prison which is a curse in itself. “Allow me to think, sir,” I answer, “I will give you my answer in an hour.” “All right.” It was not in vain then, that I had decorated his house for nothing. I see he is sticking up for me, wants to repay me. Well, I think, life is good enough pay, I may accept it, but I had better con- sult my comrades first. I returned to my cell and told everything. The whole cell darkened and fell into silence as if there were not forty men there, but dark night in a still forest. Who are the condemned locked in the fatal fourth tower? What murderers and cut-throats? Can a peaceful man in trouble live with them? At last. someone said firmly and decisively; “Go!” And the whole cell, which had almost stopped breathing for a few minutes, drew in its breath just as firmly and decisively as the one who as- signed me to the accursed tower. And so, my young people, I got ready and went. I am not so easily frightened, but while I walked through the endless gloomy corridors, smelling of dampness and, perhaps, of blood, I thought many things. And when the locks rang and the bolt scraped, I felt as though it were the scraping of my skin as it was torn off my back. Then the door squeaked like a knife across my heart, I and my baggage, that is my bedding, were pushed into a half-lighted cell, large, smelling of dinginess and emptiness. I sat down on a bare bunk, threw my luggage on it and looked—where are those who are doomed to the agony of waiting for death? Sud- denly from a dark corner I hear a deep voice, “Hello, there, friend! Can’t say we are well met. What for?” A short, strongly-built man, in a convicts’s smock and woman’s stockings, red striped with blue, came up to the bunk and gave me his hand. He was red and hairy and, judging by their strength, his hands were those of either a peasant or a laborer. No one else can have such hands. “Hello,” I answer and press his hand. At the same time a little figure comes from an- other corner, a tall ‘thin sort of figure, stretches out his hand and says in a thin voice, like a girl’s, “Hello, comrade.” Here, I remember, I could not help smiling. Such a youngster, with fair hair smoothly combed, such a thin girlish face and—the convict’s clothes which hang on him like a woman’s smock on a scare- crow. “Hello, comrade,” I say to him and, of course, squeeze his hand. gently. A gentle man must-have corresponding treatment. a press the little hand and wonder, “Now, who will come out of the third corner?” But no one else appeared. These two were the _ incorrigible criminals who had committed unpardonable offences against unfortunate humanity, whom the crown prosecutor, that vigilant watch dog of society, was to destroy by means of strangulation. Well, day after day passed, friendly-like, as al- ways among the unfortunate. The older, the red one, was by surname Marin and the other, who looked like a girl, was called Aloshenka. And here I admit, though it was not a nice thing, I became (Continued On Page Six). have you he said without taking his