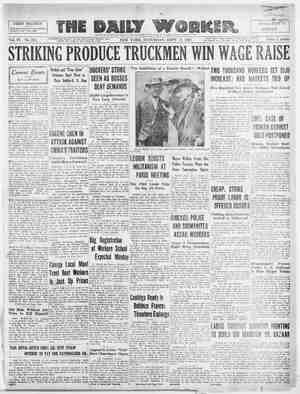

The Daily Worker Newspaper, September 17, 1927, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

The Economic Theory of the Leisure Class EDITOR’S NOTE: The following review of: Bukharin’s great theoretical work, appeared in the August issue of “The Communist,” theoreti- cal organ of the Communist Party of Great Britain. The need for intensified theoretical study is as pressing in the Workers (Commun- ist) Party of Americagas in the C. P. of G. B. The leaders of the Russian Revelution never issed an opportunity to add to their store of retical knowiedge end this book of Buk- n’s was first published in 1919 while civil war raged thru Europe. * SIO revolutionary theory, no revolutionary move- 4Y ment,” says I.enin in one of his famous pole- mics against the Mensheviks. It were well if sach a text could be hung up in the bedroom ef every British socialist, that aims at passing for a revolu- tionary. For the proletarian movement of this coun- try, except for a very small circle, still maintains its traditional aversion to theory. How much this aversion to theory is responsible for the confusion and pessimism that is rampant everywhere at pres- ent is a matter for some hard thinking to be done before our movement strikes the high road to revo- lutionary action, and ceases to prattle about de- fending, or overthrowing capitalism. Lenin’s text is of particular importance to Com- munists. There is no section of the working class movement so zealous and indefatigable in the fight against capitalism and the capitalists as the Com- munist Party. But this very zeal has its disadvan- tages, especially for a numerically small Party like ours. There is the danger—a very real danger, we think—in pursuing the manifold mundane tasks, all of which are necessary and important, of ignor- ing theory and theoretical self-study in preference to what is called “practical work.” The lack of time and opportunity and poverty amongst the workers may be added to the handicaps, but these in no way invalidate the warning, or the danger. It was the fashion when the Communist Party of Great Britain was being set up some seven years ago, this month, to talk of being realists and to extol the virtues of practice over theory, and there was some justification for that fashion at that time. The socialist movement was passing through a critical period. Thrones and governments were in the dust, or in the balance. The test upon the socialists had to be clear, simple and straightforward. The test then was, for or against revolutionary action sym- bolized in the Russian revolution; Bolshevism or bourgeois democracy and constitutionalism. But adhesion to the Soviet Republie and the re- volution brought more to the ranks of Communism than those genuine proletarians who had no use either for the bourgeois democracy or its supporters, who were leading the workers’ movement. A goodly number of sentimentalists, careerists and phrase- mongers were caught up in the tide towards Com- munism, chiefly from the side of the intellectuals. We could name a number of these who have passed through the ranks of our Party, each of whom ean be placed in one or the other of the above cate- gories. In all of these cases (it is not necessary to give names) we had a great deal of lip-service to Communism, but no understanding of Communist theory. It is a curious fact that the vilest slanderers of the Communist Party are the renegades. How often do we hear reproaches hurled at our members for their “ignorance and stupidity”? How often do we hear the Party leadership traduced and the insinua- tions made that the Communist Party would be all right if it wasn’t for its leaders? Meaning by that, we suppose, if the leaders were made up of amiable fellows with whom they would never be called upon to have theoretical quarrels, there would be room for them. The fact is that all these ex-Communists have been tested at the bar of theory and *found wanting. That, however, does not excuse our mem- bers from removing all grounds for the stigma of “ignorance and stupidity.” ‘The way to do that is to cultivate self-study, hard thinking, and more the- A useful contribution to the material for theo- retical thinking is being added to the library of Marxist literature issued by Martin Lawrence, in the translation into English of Bukharin’s “Economic Theory of the Leisure Class.” This book, the author teils us, was completed in 1914, and after an ad- venturous career, occasioned by the war, the MS. found its way to Moscow, to be published in Febru- ary, 1919. It is a trenchant and logical criticism of the famous Bohm Bawerk, the Austrian economist, who was peddled about so much in this country a decade ago by the I. L. P. and anti-Marxists, as the destroyer of the Marxist system. Our readers who remember this period will be interested to learn that, even while we in this country, and, in our own way, were defending Marx against Bohm Bawerk, Buk- harin was sitting in the class room of the University of Vienna copiously noting the fallacies of this same professor—notes that were to expose the futility of the professor’s apology for the rentier class, and to provide our proletarian movement with a first-class Aheoretical defense against the would-be destroyers of Marxism. ‘By THOS. BELL (London) Some idea of the scope of this book may be gathered from what Bukharin himself teils us. While in Vienna he went through the library scrupulously noting the standard economists. Imprisoned just before the war, he was subsequently deported, and went to Switzerland. At Lausanne, he studied the Anglo-American economists. We next find him in Stockholm in the Royal Library and, on his arrest and deportation to Norway, he continued his studies in the Nobel Institute, Christiania. Subsequently, we find him studying in the New York Public Library, U. S. A. The result is 34 pages of this book, comprising 158 notes alone, a veritable mine of information in themselves. ~- In the author’s preface, he makes an observation, as we think of timely importance for “British” Marxists. Hitherto;there have been two types of criticism by Marxists, either exclusively sociological, or exéessively methodological. “Marxists,” says * Bukharin, “must give an exhaustive criticism of the latest theories, not only methodological but socio- logical, and a criticism of the entire system pursued to its furthest ramifications.” And, regarding, as the author does, the Austrian school as the most powerful opponent of Marxism, he applied this rule to Bohm Bawerk as the representative type of this school, demolishing his entire system with that ruth- less logic associated with the name of Bukharin. “The Economic Theory of the Leisure Class” com- prises an introduction, five chapters, and a con- clusion with a critical article on Tugan-Baranov- sky’s Theory of Value, as well as an appendix, notes and index. In his introduction, the fundamental tenets of Marx are vindicated, i.e., the facts of con: centration in capital, the syndicates, trusts, bank- ing organizations, and their penetration into indus- try. Two tendencies are in opposition to Marxism; one, the historical school and the other, the abstract school. Faced with competition from England, the German bourgeoisie demanded protection for its national industries, and the German protective tariff movement became the cradle of the historical school. This school was a reaction to the cosmopolitanism of the classical economy. Being negative towards abstract theory it landed into a narrow-minded em- piricism, reminding us of some types of “theorists” here in England, who spend their time collecting conerete data, while leaving the “laws” till later. From the historical school we get a history of prices, of wages, credit, money, but no theory of wages, ‘no theory of prices. Karl Menger, as father of the Austrian school (though Bohm Bawerk was its most outstanding representative) waged war on the historical school. After carrying off some victories, Menger turned on Marxism. In essence, the new “abstract” method is in complete opposition to Marxism. It is the bourgeoisie on its last legs. With the development of capitalism there appears the rentier class of mere coupon clippers, owners of gilt-edged securities. This section of the bourgeoisie is not a true class, It is only a parasitival group, playing no creative part in industry. It knows no social life. All social bonds to it are loosened, It has no intereste in social wel- fare generally. Its one obsession is fear for the proletarian revolution. fi In contrast with this rentier or leisure class, the proletariat are held captive in huge cities. It readily acquires and develops a collectivist psychology, with keen sense of social honds and social welfare. The proletarian class has no fear of social catastrophe, am 4 on e since it knows it must destroy, and clear away the refuse of capitalism before it can build. Thus, we see the difference between the Austrian school, and Marxism as a social psychological contrast. Having explained this contrast, the author goes on to analyze it from the standpoint of logic, with a treatise on objectivism and subjectivism ‘in po- litical economy. Since Marxism deals with the causal chain linking up social phenomena, and sees a social process independent of individual motives, it is ob- jective. On the other hand, since the labor theory of value of the classical school, particularly Adam Smith, is based on an individual estimate of com- modities, corresponding to the quantity and quality of labor used, it is a subjective theory. The method ‘of Marx is not to start with individual motives. As buyers and sellers, individuals go to the market, the product dominating the creator. No doubt, there is a connection between individual and social wills, but Marx’s method is to examine and ascertain the law of the relations of this social phenomenon. The method of the Austrian school is to abstract the historical and organic methods, and start from the “atom.” Thus we get, as illustrations, - “a man in a desert,” “an individual in a primeval forest,” and other variations of the “Robinson Cru- soe” legends, forgetful that the economic motives and categories associated with the illustrations, come from a definite social relationship. It is as if we were to speak of dukes, earls and lords in primitive ancient society, to endow these terms as being eternal. Modern political economy can only have as its object a commedity society, i.e., a capitalist society. In this society the individual will and purpose are relegated to the background, as opposed to objec- tive social phenomena, Only in a socialist society will the blind social element yield to a conscious cal- culation by the community. Relations between men being simple and clear the fetishism attached to the present relations among men will disappear. The unhistorical and subjective. method of the Bohm Bawerks is particularly revealed in their de- finition of capital, where the stone of the ape and .the club of the savage are classified as the germ of capital. In contrast with Marxism which defines capital in accordance with its historic use, viz., a means of producing wealth with a view to profit, the Austrian school limits capital to being merely a means of producing more wealth, i.e., as universal for all time. Yet another fundamental trait of the Austrian school is the emphasis laid upon consumption, and the consumer. Whereas the classical school ap- proached the economic problems from the standpoint of the producer, individualism finds its parallel in this subjective-psychological method of the “Robin- son Crusoes” of the Austrian school. Its ideology is the elimination of the bourgeoisie from the pro- cess of production. Passing to the newer Anglo-American school, rep- resented by Bates-Clark, Bukharin shows us it is not difficult to find the ideological basis of this school. This basis is to be found in the process. of the transformation of industrial capitalism to mili- tant imperialism, and where the less individualistic become trained in organization of entrepreneurs. The method of investigation is social-organic. The American school, the author warns us, though the product of a progressive bourgeoisie, is nevertheless a declining one. ° It is interesting to note that this theory of mar- ginal utility was put forward mathematically by a German, Herman Gossen, as far back as 1854. In- deed, many of the theses ascribed to the Austrian and Jevonian school are to be found in Goosen’s work. This the English Professor Jevons acknowl-_ edges. But the international rentier found his learn- ed spokesman in Bohm Bawerk. In Bohm Bawerk’s theories he found a pseudo-scientifiec weapon, not so much in the struggle against the elemental forces of capitalist evolution, as a weapon against the ever- menacing workers’ movement. We think we have said enough, however, to arouse the interest and curiosity of the reader, to procure this most important book. From the marginal utility theory of value to the theories of profit enmeshed in statistical formula, Bukharin pursues the fallacies of these apologists of capitalism with irresistible logic, revealing their theoretical work to be a “barren desert,” In his introduction, the author says, “It may ap- pear unusual that I should publish this book ata moment when civil war is rampant in Europe. Marx- ists, however, have never accepted any obligation to discontinue their theoretical work even at pe- riods of the most violent class struggle, so long as any physical possibility for the performance of such work was at hand... A criticism of the capi- talist system is of the utmost importance for a proper understanding of the events of the present period.” : This understanding, the British workers need now more than ever. This book of Bukharin's will prove an indispensable help. “Phe Eeonomic Theory of the Leisure Class,” by N. Bukharin is issued by the International Publishers, New York, and can be secured also from the Daily Worker Publishing Co., $2.50, * LAE