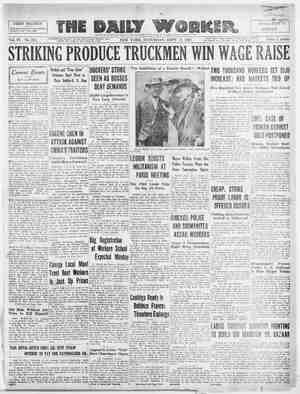

The Daily Worker Newspaper, September 17, 1927, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

A Critic Earns His Thirty Pieces of Silver VEN anarchist-socialists, who ought to know better, and of course social-democrats, of whom it would be expected, have been deceived by polemicists of the capitalist press when the latter charge Sovict Russia with the heinous crime of “Standardizing the Human Soul.” No part- truth could be more untruthful; yet T. R. Yzarra, reporting to The New York Times that “A German Critic Sees Russia Exceeding America in Uniformity,” selects that age-old prevarication to entitled an article " whose bald-faced fact-twisting would do credit to a seventeenth century Dominican. Herr Rene Fulop-Miiler, we learn from Mr. Ybar- ra’s report, has made an intensive study of Soviet Russia, starting out with an unbiased mind, and, upon the conclusion of his investigation, finding that “Bolshevism is a great peril to society.” Me- thinks I have encountered the quotation before— but before we indulge in sarcasm at the German critic’s expense, let us see if he has presented any new promises to support this cob-webbed deduction. Mr. Ybarra, in his report, is reviewing Nerr Fu- lop-Miller’s “The Mind and Face of Bolshevism” and “Lenin Und Gandhi.” It has not been my good fortune to be able to procure these books, and since I have not read them, I shall not indulge in the popular sport of capitalist-reviewers and attack them without first a reading. But I have followed Mr. Ybarra’s report very closely to his last punctua- tion mark: he it is upon whom my gun is trained. If Herr Fulop-Miller turns out to be “the man be- hind the man behind the gun,” he also will be sub- jected to polemical attack. What is Herr Fulop-Miller’s impression of Rus- sia, after “an exhaustive and unbiased investiga- tion”? “Everything that happens in Russia today” (I now quote from “The Mind and Face of Bol- shevism’”) “happens for the sake of the mass; every action is subordinated to it. Art, literature, music and philosophy serve only to extol its im- personal splendor, and, gradually, on all sides, everything is being. transformed to the new world of the ‘mass man’ who is the sole ruler.” The result? As Mr. Ybarra says Herr Fulop- Miller found it, “they shouted their command to the Russian poets” and lo! a new ‘mechanized’ poetry arose in the land. They regimented the philosophers and svon the outlines of a new stand- ardized philosophy, ruthlessly opposed to everything idealistic, to crown the victories already won in the domain of polities and economics. They issued their orders to the Russian sculptors and soon buildings and monuments dotted Russia, conceived accord- ing to the dictates of the new “machine art”—huge embodiments of the revolts against’ all that which in the past had meant art to mankind. They wayed their magie wands in the direction’ of the, Russian theatre and: up cropped ‘a new form of: ‘drama, more radical than anything hitherto dreamed of— playhouse without any stage, actors dancing on wires over the auditorium, gymnastics instead of dialogue, “the most extraordinary physical distortions giving an impression of ‘complete insanity.’ “And the new Russian music that sprang to life was of a piece with all this, with its ‘conductor- less orchestras,’ and similarly revolutionary mani- festations. As for religion, the Soviet dictators were inexorable in trying to uproot everything resemb- ling religion as it was in the Russia of the czars. And all this for the ‘collective man,’ the ‘dividual’.” Mr. Ybarra, in condensing Herr Iulop-Miller’s ob- servations, has turned many,a pretiy phrase. But pretty phrases have an unfortunate habit of meta- morphosis into boomerangs, under the critical eye of the honest logician. i Not only Communists, but many capitalist social- ists, acknowledge this to be the “machine age.” Insofar as economies is akin to liter- ature and art—and I am sure Herr Fulop-Miller will admit the relationship, the literature and art of , the period will always be a part of the period. Therefore, what Mr. Ybarra, and Herro Fulop-Miller are attacking is not the mind of Bolshevism, but the age of Bolshevism. The art of a period must be of the same stuff as the period itself. Even Mr. Ybarra cannot change the trend of arts and letters. But—does this result in standardization? If the Russian audiences encourage stich innovations as “conductorless orchestras,” “stageless theatres,” is that an unhealthy attitude? Conducted“orchestras, and theatres with stages have their exponents every- where else in the world. Experimenting with art, and the encouragement of such experimentation, is, to my mind, the manifestation of greater in- dividualism than one can find in any other nation. But Herr Fulop-Miller and Mr. Ybarra would have us believe that all orchestras are without con- ductors, all theatres without stages—that the Rus- By WILIg DE KALB ‘ sian leaders “shouted their command and lo!” every- thing became standardized. If this were so, why is it that the Russian peasant is as familiar *with the photoplays ef Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pick- ford as the German salesgirl? Or the novels of Jack London? Or the sweet strains of Dvorak? Certainly these literary gentlemen must realize that the revolution, the Bolshevik revolution, is still on in Russia. Where formerly the struggle was between Red Guard and White Guard, now it is between Communism and Capitalism. It is revo- lution, none the less, as bitter, and as revolutionary. Then, why should not the art of the period por- tray this transition period? Is it “standardization” when it does so? Of course, I know that their quar- rel is not with the art of the period, but the period itself: but, were it the art, they would have to change the age-old tendency of art to represent its era. for all of me, they may try. Just what is this terrible “standardization” under which the Russian suffers? So far as i can see it, Herr Fulop-Miller must consider me to be standing on my head, for only in Russia can I find individual- ism, and everywhere else standardization. In Rus- sia, the worker, having a voice in the factory sov- iet, can express his individuality in the manage- ment of the affairs-of his business. Can the worker in any other country do the same? In his factory unit important questions of government are voted on. His. representatives ritin his government, he paints his own pictures, he plays in his own orches- tra, he acts in his own plays on his own Stage. He does not, as in America, hire a sort of priest-craft to supply art, literature, music and theatricals. In all of these he plays his own part—and, considering his inexperience, he does it well. More than that. In what other nation is the gen- eral public so interested in national affairs? In in- Fair Day By CORRINE M. GRAYSON. AIR DAY! A half mile track surrounded by a wilderness of Mencken morons. Boys sing-song- ing “Ice-Cold-Pop-Lemonade-Ice-Cold-Pop-Lemon- ade.” Shouting from the dilapidated grandstand for favorites. Band blaring underneath. Tents. Bally- hoos. “Boxing inside, 25¢ admission. Moral and Refined.” Monkeys chained to little tin autos, melancholy beasts, blinking frightened eyes at the children of all ages poking at them beneath the curtains. ; : Hot dogs. Waffles. A lost urchin rubbing grubby fists in tear-filled eyes. ‘A stable full of pigs, un- believably fat. New-born litter sucking and squeal- ing. Cows in a bigger shed. Sleek, mild-eyed. Well- bred. An underfed, flat-chested, pot bellied girl holding a ricketty baby pities the poor dumb beasts. The ma-a-ing of sheep in the next building brings a crowd to watch the shearer, solicitous of their comfort and appearance. The prize-winning cows from the State Insane Asylum. If the occupants of that institution had only had such prenatal care as the cows upon which they feed. An oasis is the Fine Arts Builling—not because of the fine arts, but because of the tempting array of vegetables, fruits and the cooling fountain in the center. Fine arts! daubs of patriotic and sickly sentimental appeal. Commercial signs and posters! Outside the sun is hellish. Dust clogging the pores and stuffing the nostrils, kicked up in miniature yellow clouds by stumbling, vapidly staring passers- by. 5 “Bye-Bye Blackbird”-—the’ merry-go-round’s cal- iope always a year behind with the popular songs. Flittering red and green birds at the end of sticks. Ferris wheel creaking as it bears its burden of giggling, screaming youth, | Strutting policemen, swinging sticks, ogling, de- manding free drinks and getting them, Solemnly a six-foot gawk stands in the shade of a ticket win- dow, chewing ice-cream candy, mouth red and white patches. Pop-pop-pop of air rifles. “Right this way. A dime, ten cents for the bigg*:st show on earth.” Torn paper, lunch boxes, tin foil, cigarette butts, whorls and eddies of dust. Tired faces, dirty brats, powder-caked. noses, scowls, honking horns, clang- ing, crowded trolleys. Fair Day! ' ey Spt ternationa; affairs? Of their own accord, groups of workers express their interest, their opinion, their sympathies, °n al! important international questions by means ¢f resolutions, parades, demonstrations, funds. Nicaragua, China, Passaic—questions about which the average worker knows little, if anything, are of intense interest to the Russian of today. Standardization? I cannot understand how even the most dishonest hypocrite could apply it. Let us see how much individualism is manifested by the workers in other lands. ‘All must slave for their wage. They have no voice in their government or their industry. heir “culture” consists in read- ing those books that are read the most; looking at those pictures that are praised the most; seeing those plays that have been seen the most: hearing that musie that has been heard the most. National affairs they are not interested in; their newspapers print, instead, crossword puzzles. International af- fairs? So far away—dismissed with a shrug of the shoulders. Standardization? I know no other name far it: Formerly, sociologists were of the epinion that the individual could only express himself in his leis- ure time. The soviet system of the conduct of in- dustry has: proved this to be partly a fallacy. Even in one’s working hours one can be himself. But leisure provides the greatest opportunity. True. And under Communism, the individual will secure greater leisure. Certainly not under capitalism. “But one moment!” I can imagine Ybarra ‘and Fulop-Miller exclaiming. “You are considering only the workers!” Certainly. And so are they. For Russia is a workers’ country. There, they claim, the workers are standardized. In capitalist countries there are workers and idlers. These, I claim, (and in some instances, Herr Fulop-Miller agrees with me) are standardized. How then, do the writers make out a case for their conclusion? Let us examine their phrases. “They shouted their command to the Russian poets. . .” I see Herr Fulop-Miller has read the Pravda. When Josef Stalin, secretary of the Rus- sian Communist Party, writes a critical article on the poetry of the day, complaining that the poets are writing about the October Revolution when they should be giving their energy to the transition period, which is comparable to a criticism of Georg Brandes who once charged post-war literature with sustaining post-war turbulency, is that ‘Sssuing or- ders.” “shouting commands,” “regimenting,” “wavy- ing magie wands,” or is it not the same type of criticism, performing its function, as we find in capitalist countries? One must not be harsh with Herr Fulop-Miller for this poor choice of language-—it would be con- fusing to, him, finding a politician, and a peasant, who also has an aesthetic sense, and is qualified as a literary critic. It rarely happens elsewhere, except in Russia. Out of generosity, these pretty phrases of Mr. Ybarra and Herr Fulop-Miller might be dismissed as unconscious ranting. But then, in the face of contrary facts, they charge “as for religion, the Soviet dictators were inexorable in trying to uproot everything ‘resembling religion as it was in the Rus- sia of the czars.” : What was really done? The grafting, lying, im- moral and discrepit clergymen were given their walking papers. Honest priests could do business so long as there.was a demand for their “sacred” wares. Is this “inexorable”? Instead of the head of the government encouraging people to go to church, they were encouraged to learn to read and write. “Inexorable”? I suppose Messrs. Ybarra and Fulop-Miller, in a Cook’s tour of Russia, stopped long enough in Moscow to see an inscription, “Re- ligion is the opium of the people,” near a cathedral. The inscription does make one inclined to adjectives like’ “inexorable,” if one is a capitalist apologist. . But it does not deter any Russian, if he is religious, from enjoying his daily or weekly hypodermic of religion. Since the Soviet government came into power, the monopoly on religion has been taken away from the Orthodox Church, and all churches, if they are kept clean, and do not graft, can go on dispensing their narcotic till the customers are fin- ally satiated. “Inexorable’? In hurling insults, the writers have merely hurled boomerangs. It is apparent then, that Herr Fulop-Miller has proved nothing. In finding that “Bolshevism is a great menace to society,” I should like to call him mistaken; instead I must use a harsher word, I must accuse him of dishonesty. > I can only label him a critie turned hypocrite. His usage of the old red herring as a conclusion, and premises as absurd as biblical astronomy, have re- vealed him>to the discerning reader to be a literary Judasy a critic who betrays the confidence of his readers. And I think, due-to the ponderous nature of his books, capitalism will cheat him of his thirty picees of silver. : : eee RE a: RP nner sree nnn nme