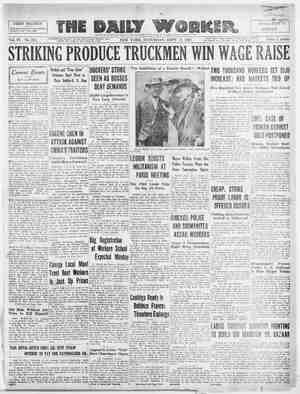

The Daily Worker Newspaper, September 17, 1927, Page 10

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE FOURTH TOWER (Continued From Page Five). more curious every day. For what crimes were these two people, so different, the direct opposites, one might say, to be led to the same death? I could not ask, somehow; the unfortunate are always supersensitive and most secretive. I drew close to them, closer perhaps, than I had been with those who argued political wisdom in the common celf but who can cooly remind a dear one that death awaits him? . Aloshenka made figttres from bread and drew a chess board on the boards of the bunk and taught me to play that wise game; we sat long days at it, he—awaiting death, and I—suffering for them both. The tireless Marin, in the red stockings striped with blue and the torn convict’s shoes, danced about the cell exactly till two o’clock mak- ing endless circles about the table which stood in the centres Two o’clock in the morning—it is a fearful hour, when from the tower they take a living man and lead him away to be hanged. And so Marin dances about the table, singing a sor- rowful prisoner’s song, usually the same one, “T stand on the keecha, Keecha so high, Take a look at freedom, Freedom nowhere nigh; Weep no more, Marusia, For mine shall you be, When I’m free Marusia You shall marry me. ° He is about forty-five and so strong that, it seems, if you harness him to a plow and yell loudly, it will cut a deep furrow. As soon as two o’clock comes, we at once lie down to sleep. Marin sleeps a deep, calm sleep—till to- morrow; and Aloshenka and I talk for an hour or so of his mother, of his little sister, Tanechka, who had passed with honors into the sixth grade of the gymnasium; Aloshenka had already been in the sev- enth year. He was sad because it was harder for Tanechka now that he no longer helped her with her studies when they came home from school.+ And Aloshenka also talked of his sister’s friend, of darkehaired Dunia, or Deena, as he tenderly called her, who had large, deep dark eyes and thick dark braids, a white neck and a delicate, somewhat olive-tinted face. Of her he spoke willingly and long, told how they walked on a high rock by the Volga, delighting in the many-colored lights of the ships, listening to the music of the ship’s whistles. And Aloshenka also told how on some holiday they gathered in the fields, about fifteen of them, all young, Dunia or Deena, the same with the thick black braids, his little sister, Tanechka, gymnasium students and even one university student who was a relative. They stayed there till dark, playing, chas- ing about. In the games Aloshenka’s cap was knocked off, the cap with his school emblem, Off went the cap like a ball, into the ravine. They searched for it, but what’s the use; it was spring and in spring the nights are dark. They did not find the cap and Aloshenka went home with nothing on his head. Then of all the luck—The same night and in that same ravine, expropriators had either been sharing or just unpacking the money taken from some gov- ernment wineshop. The police found some wrap- ping paper, other scraps of paper and, a short dis- tance away—Aloshnka’s cap. And hy this aap within a week they traced Aloshenka. He was ac- \ cused of participating in the expropriation and the court found the evidence sufficient—a court mar- tial does not trust witnesses overmuch—and so, just because of that cap, the damned prosecutor de- manded that Aloshenka be condemned—to death by hanging— “Mamma has gone to St. Petersburg,” says Aloshenka, “she is sure to get a pardon for me. We have friends there.” “Of course she will get it,’ say Marin and I. “Don’t fret, Aloshenka.” “T don’t fret—’ e “Let’s have another game.” “All right.” And we play. He plays absent-mindedly and though I could understand this wise game, this same chess, I give in to him, losing all the time. “You do that on purpose,” he says. I put on a hurt, even angry look. “Try to beat you! You’ve played thousands of times and I am only learning. You just wait till we are free. I’ll come over then and we'll play a real game of chess.” “Be sure to come.” And for the hundredth time he tells me his ad- dress. It is often so with people; one tells something of himself, speaks frankly, and then another wants to tell his seerets. Marin came and sat beside us on the bunks; we pushed away the chessmen on seeing his sad, thoughtful face. We understood and prepared to listen to his death-bed confession. Marin’s collar was unfastened, showing his strong broad chest, covered with red hair and in this guise he looked like a robber. His voice was somewhat hoarse, his eyes had a dry heavy look—I have seen such eyes in large animals locked in cages. He was a peasant from the village Marashkina. It seems there was some church holiday and there had been some drinking. The vodka was gone, they wanted more, and there was no money. They decided, he and his brother-in-law, to scare a cer- tain old woman of their village and then ask her for a rouble for vodka. They smeared their faces with soot, took an ancient revolver which could no longer shoot, and went off. The night was dark, the old woman lived alone. They knocked. She was still awake. She came down the stairs with a candle, opened the door-—she had recognized their voices— and when she saw their bsmeared faces, she only stopped to scream before she plumped down with heart failure. As luck would have it, the police sergeant was also coming to see her, probably to make a loan too. He heard the scream, rushed up. There they were, no place to hide, faces blackened, a gun in their hands—an apparent case of exprop- riation. He assumed his official dignity, locked them up and later sent them to the provincial capi- tal and there—the court martial. Painted faces, a revolver, a dead hag—-what other evidence did they need? And so, my young people, another death by hanging. re We live together for four months. Marin had been awaiting death for six and Aloshenka—almost that. It is hard on Aloshenka, he gets tired of evenings, maybe the nerves grow numb or the heart is turning to stone but he began to fall asleep early in the evening. It is not midnight yet and his eyes begin to close and his head nods over the chess- board, he makes false moves. Every evening Marin dances about the table, chanting his song, and what should I do? I lie on my hard bed and think that there are no paints in the world to draw the depths of agony felt by. a strong man who waits whole weeks and long months for an inevitable and violent death. é And so, one night, near two, when Marin was dancing about the table and quietly singing his sad little song and Aloshenka was sleeping, we heard the squeak of the lower door leading into the tower, the clash of footsteps on the stairs, the squeak of the second door and at last, at our own door, the clatter of the lock and the scraping of the bolt— Four armed men came in. And as soon as they had come in Marin went toward them, as though to give himself to them quickly, if only they would not touch Aloshenka. But they had come for him, for Marin. And Marin, with a chalky face, laid his finger to his lips, that they should make no noise, should take him quietly and not wake Aloshenka— quietly, on tiptoe, he came up to me, embraced me warmly, gave me a warm kiss, threw a farewell glance about the cell, bowed toward Aloshenka and— Do I remember anything of the night I spent over the sleeping Aloshenka? I remember only the morning, remember only his awakening. Would it not have been better had he never wakened? He awoke as though someone had set a spark to him, jumped up, sat down on the bunk and gazed long at the place where Marin always slept. Then he fell Wall Street After Six Here stillness reigns where once the babble broke Of greedy tongues and bankers sat at ease Surveying profits far from grime and smoke Of mills and mines and ships upon the seas. Whence comes these profits. A belated clerk Goes homeward now and here a painted drab Steals by to rendezvous. Scrubwomen work Far through the night. Here wends a lonely cab. And here I ponder on the broken hearts Of small investors and the bloody fray Of empires built and shattered on these marts, Of wars made here, ef murders day by day. Mad street! You are at rest a little while Ere comes another day with eries and noise Of frenzied trade. And so I only smile And think of how some day your eager voice Shall die when workers come into their right And profits have an end and man shall dream No more of wealth. I leave you to the night And that great day when labor rules supreme! —HENRY REICH, JR. on his straw pillow and sobbed. And in his grief I heard only one complaint. “Tt—it was not—fair—how could he go—without saying goodbye—to me?” . Then Aloshenka grew silent and was silent a long time, for whole weeks and even stopped playing chess. He did not sleep whole nights. Marin’s exe- cution must have reminded him of his own fate, just as horrible and merciless. He had been here seven months already, awaiting death, and it was near six months that I had been bearing my punish- ment for resenting an insult. And so one day a jailer comes to the cell, looks for me in the gloom with his eyes. “The governor wants to see you in the office.” I.go. Our footsteps echo hollowly in the grey and empty corridors, the rusty door-hinges squeak protestingly. In the office, as the other time, the gloomy governor sits bent over a heap of papers and makes me wait just as long by the door. Then he says sternly: “Well, now you have served your punishment. You may return to the common cell.” He lifts his head and looks at me as attentively as though he wanted to ask me something impor- tant—and could not. And here I felt that he was a man. “T can’t, sir,” I say, “leave me where I am.” The governer moved in his chair as though he were going to spring up, then his head sank as though he were bowing and he moved his hand slightly as though to say, “Very well. Go.” And again I was with Aloshenka who, I may say, met me with eyes as expectant as if he had been awaiting not me but his pardon. And when he un- derstood that I was not to leave him, became talka- tive again, and then and there we sat down to our chess. ~ I stay there with Aloshenka another month and another} no one else was brought in, thank God. Most of the time we talk about how hard it. must be for his mother to do so much in St. Petersburg because she has not enough money to bribe the necessary people. Aloshenka’s father had been a doctor, of small practice I suppose, and did not earn much, most of his patient being poor laborers and clerks. “Well, somehow or other,” IT say, “she is sure to get a pardon.” And; he, to reassure not himself but me, assents with a tired smile. “She is sure to get it. My little mother is very insistent. She’ll go to the minister himself.” She may be insistent but now Aloshenka did not go to sleep till almost three. And often I noticed that he pretended to be asleep to quiet me and I too would pretend to sleep. We were not allowed to put the lights out for the night and we usually slept together, face to face, in one bunk, and so I open one eye to see if. Aloshenka is sleeping and there is one of his eyes slightly opened. He is watching me too. Once, when we caught each other at our trick, all at once it seemed so funny that we did not sleep till morning, even sat down to chess and played right up to roll call and then began break- fast. And so we didn’t sleep all night. But all this was nothing., From that very night there began in both of us that disease they call insomnia. We could not have slept if our eyes were sewn up. Great God, we grew thin in one week, like living skeletons, eat we could not, our noses grew sharp, eyes liké coal, became delirious, we began to see all sorts of nasty visions, like sometimes we would hear them coming and could even hear the doors squeaking, the locks clashing, hear the rattle of locks, voices, Aloshen- ka’s name called, and once we both heard clearly, “We might as we hang Michael Vanitch too.” Yes, things began to go wrong with us. And so, at this same unlucky time, about two o’clock in the morning, when Aloshenka and I were playing chess, playing so that he moved both his men and mine and I too, the game seemed to drag, neither could win—and so they came. ;: They came. . .came with the strait jacket, thought he would resist because he was young, only seven- teen, was not prepared to die, perHaps—well, and so they decided to prepare him themselves. But he was ready, and I, I might say, with him. . .I can’t remember it all. And the strangest part was he went to death gladly, he saw in it the end of his suf- ferings and, perhaps, wished to rid me of mine. . . even the jailers were surprised. Only he lingered a moment on my breast, and his bv was so white” and his blue eyes burned with a flame I had never seen before, the eyes which now looked black, deep and bottomless. ‘ _ He did not cry. Kissing me thrice, like at Easter, Aloshenka slipped out into the corridor, the jailers followed, the door slammed, the bolts scraped, the lock clattered and—two months later I came to in a padded cell. . . .The night is so beautiful, everything is so happy, in the Volga is not water, but the real blue, what we painters call ultra-marine—and the lights glow so brightly, red and blue and yellow. FAC ena AOnET Mb SRNR (