The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, October 25, 1903, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

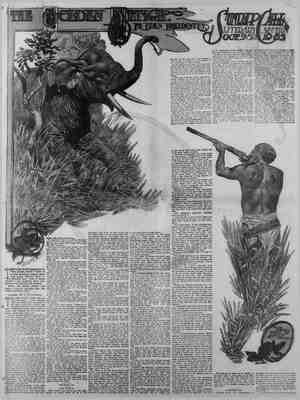

'MALLORY'’S By ¥ Trevelyan. , + ILE it usually hap- pened that Mallory got what he wanted in the world it was by no means due to chance. When he wafited anything be began by looking the fleld over carefully, noting all the salient points—the advantages and the disadvan- tages. Then, with his feet up and & cigar tween his lips, he would consider all eveilable methods of securing the thing Gesired He was & handsome, vigorous man of 50 years when business affeirs making it necessary for him to spend & number of months in New York a letter of introduc- tion secured him the very delightful privi- legpg of rooms with the Fosters, whose story of waning fortunes he had heard from the friend who sent him to them The ominous length of bis upper lip w: ‘ Bertha - hidden under a short, gray mustache, or Miss Foster would have known from the first that it was useless to oppose him »d was set upon anything. ce of his youth was & beauti- as faint and elusive scent of lavender. But he had been it for twenty years, having been & widower with two children. at in the great dim drawing-room, everything was eloquent of other days, awalting- Miss Foster's appearance, he noticed eral things—touches unusual in stif city drawing-rooms, but which made for homeness. He sighed with a altogether out of keep. ing with his height, breadth and florid- ness In the midst of his r appeared, her delicate slightness height- ened by the massive doorway in which ehe stood framed for 2 moment. As he rose to greet her he wondered 1dly what could have given her that harassed look— with the oval face and Her smile, he thought, and girlish, and in a few were talking with the ease acquaintance. like air that sat amus showed him the rooms verie Miss Foster and uncertain income, and ext day found him installed in them. Often g the following monthe he an hour with the mother ¢ with hidden amuss the lhtter's unnatural little air of riiness. She would forget and laugh yly at times. Then, in a mo- e seemed to remember that she onger young, and she became e the saic, careworn woman wing her mantle of years un- about her. It was as If she U t to be surprised by rushed out to meet it. His speculative glance now told him that she could not be more than 40, 1f she were t But by the way in wiuch she was always ting forward the oung girle of her acquaintance it was hought herself too old erest to any man. old regime,” Mal- nd has probably con- sidered herself an lady ever since she emerged from ber teens. She hasn’t been sbie to assimilate this bachelor-woman and he smiled to himself. ne way, Miss Marion,” “I have tickets rrow night he sald for the Be good and ere was a flash of surprise in her that for one brief, fleeting moment ly that he must have taken his senses. Then courtesy pre- and after hesitating for ap- ble moment, in which it was ap- hat she was casting about in her 1 for some plausible excuse, she ac- the time arrived she was dis- an uncomfortable conscious- had the air of a person who that she was going to be a subject ckly exchanged glances and half- g commen All this Mallory di- forth every effort to arself to such good pur- d of the evening she chatting &s unconcern- Grundy did not exist. beginning things this excellent (Copyright, 1003, by T. C. MeClure.) HEN Morris heard that the freedom of camp life was to be disturbed by the advent of girls, unlike the right good captain of the Pina. fore, he was gullty of & “big, big D.” Holbrook and Beaton looked sheepish. They and Morris were a trio of Yale se- niors who had slipped away from New Haven in the interlude between the clos- ing of exams and commencement for one last jollification at Seaton’s summer home on the Sound before they went their sev- eral ways. To him and Holbrook the plan had seemed rather a nice one. “Oh, come, BiL” said Holbrook. “They're awfully jolly girls. It won't be s0 bad.” “Oh, of course not,” returned Morris scornfully. “I know how it will be. We'll have to wear collars and shave and do the “sassicty’ act. They'll think it's too cold to go in swimming, and they won't know how anyway, and they'll expect to be taught. They'll insist upon going salling, and they’'ll scratch all the paint off the @eck with their high-heeled shoes, and - —_— ‘went smoothly for & while. Walks, drives and theaters followed and apparently Miss Foster's feir of appearing ‘‘kitten- ish” slumbered. To Mallory éach hour spent in her soclety’ made him long for more. Bhe was so deliciously contradic- tory. Then, of & sudden, all the old, prim re- straint returned to her manner. Three consecutive invitations were refused with excuses 80 fiimsy that even the most ob- tuse person must have seen through them. As before, he divined the meaning of it ell. Some 1dl her dormant sensitiv writhing under i{t. She doubtless imag- ined that people were saylag that that old maid, Marion Foster, | ng to catch Mr. Mallory, and her nner was her flerce, wordiess refutation of it. The lines el heart ached for her. “] want to speak to you, Miss Foster,” he said In a determined way, he was about to pass him in the hall one day ‘with her usual brief greeting. #he replied somewhat un- they sat down in the “Something i bothering you,” he began, fixing his glance searchingly upon her. “Come now, be frank. If there is.any way in which I can be of service to you, tell me.” nothin, she protested hastily, least, nothing much.” Then with attempt et lightness “she added, ‘Women who have neither fathers nor brothers to look out for them often have to worry, you know.” Another sort of woman might have sald “husbands,” but to Miss Foster, whose consclousness upon the subjects of 1o nd matrimony wae as shrinking as that of young girl, such a rema would have been impossible. Even In that moment Mallory chuckled to himself, yet would have liked to take her in his arms and put himself between her and the world forever. “Marry me,” he sald softly. “Give me the right to take care of you. I should count it a great happiness.” Her face went scarlet. “Such a subject ms scarcely the proper one for jest,”” she retorted with dignity. “If you will excuse me, I have duties to attend to,” and she rose to leave him. “One moment."” His volce rang a trifle sharp and clear with command. The Mallory who achieved what he wanted ifi life was speaking. Miss Foster seemed to feel this, and she sat down again as obediently as a child, though he could see that her hands were quivering nervously. “You have misunderstood me,” he said in a calm, decided voice, which somehow thrilled her with the certainty that he would bend her to his will. “I have no intention of indulging in the “Jim was lying in his bunk.” | they'll scream and get seasick if it's rough. And the chaperon will corner me and bore me stiff asking me about my studies and whether I'm any relation to somebody or other of the same name Who graduated in '67. No, thank you! None of it in mine.” Accordingly, when Holbrook and Sea- ton, shaven and shorn, in immaculate neg- ligee shirts, collars and white ducks, came down to the pler to help the girls and their youthful chaperon ashore, Billy was discovered in a ragged flannel shirt, open at the throat, a pair of old golf trousers, rubber boots and & three days’ growth of beard, engrossed in manipulat- ing a long fishpole off the neighboring rocks. Holbrook and Seaton marched off up te the house, carrying dress suit cases, and Morris saw them no more that night. He cooked his solitary supper, smoked his solitary pipe and turned in early. With a feeling of righteousness, he woki at € in the sweet, cool June morning, and getting Into his bathing suit proceeded down to the dock for his morning plunge. Holbrook and Beaton were still sleeping the sleep of the just and the midnight rollicker. The tide was high, the air filled with the sweetness of honeysuckle and musical with the call of birds. A giri in a red bathing suit stood at the end of the dock in the early sunlight. Morris was in time to see her throw her bare arms above her head, spring lightly upward and descend in & stralght limbed dive into the rippling water. ““Great Scott!” he remarked to himself, “that was a corking dive, all right.” He waited until she appeared on the surface, swimming on her side, and then, with & run and eap, was after her. She glanced back she heard his splash and smiled as he came up blinking. “Good morning,” she called. “Better mot §o too far to the east' he called back. “The tide’s running pret- ty swite.” y'-nnuu." she and swept away with long, even strokes, in the op- posite direction. Morris caught up with her. ‘““Water's pretty cold this morning,” he affably. Cold as your welcome ,"" she enswered, showing her whité teeth. “But I like it, It's exhilarating!” She turned over on her back and float- ed contentedly, Morris was somewhat abashed at the slight ambiguity of her re- marks. Presently she swam toward the dock and Morris saw her climb the slippery ;mnuarunmuvultom"flh- ouse. Twenty minutes later he found his com- panion of the waves sitting on the dock hair down drying it in the sun. Morris etill wore the disweputable trousers, but his white sweater was pass- ably clean, and he wore golf stpckings and yachting shoes, It was noticeable that he had just had a remarkably clean shave. He was meaning to take a little sall before breakfast. EADINESS sentimental talk of a man of 25" he went on, taking one of her slim hands in his and looking at her a bit quizszically. “Love, of course, is & matter of years. A man and woman of 50 would only be ridiculous if they essayed to speak that langua, “But I'm only 38!"” she exclaimed, sur- prised into protest. Mallory could have roared with laugh- ter at the innocent “only.” As he had supposed, then, it was not that she really , thought herself outside the pale—it was only that of one sensitively afraid that she ought to think so. He could not entirely banish the teasing smile from his eves, and she felt vaguely that she had walked into the trap he had set for her. “But, of course, it's absurd for you to say such things to a woman of my age— and for me to listen,” she continued cour- ageously, though Mallory noticed that she no longer made as if to leave him. “My dear Miss Foster,” he sald per- suasively, “we won't talk of that phase of the matter at all. I should not be say- ing this to you if I had not a very deep regard for you—and you, I fancy, would not be listening.” There was a little incoherent murmur which he took for assent. Then he con- tinued with an anxious air: “But there is an ethical side to the mat- ter that persons of our age should con- sider. You would be doing a beautiful act if you would take my children and me in hand, and I could make things so THE SUNDAY CALL. “A little hand clawed the air.” sunburnt “much easier for you and your mother.” “That will bring her,” he exu.ied to .himself, “But I thought your children were grown?” “They're over twenty,” he admitted boldly, “but that is the very age at which young people most need the controlling influence of home.” He could see that she was weakening, and he wisely refrained from further per- suasion, murmuring only, *“We need you, dear.” (AR e S S SR T B e On the steps of her new home, as the carriage dashed up the drive, she noticed that a small group awaited them. A mo- ment later she was clasped in a bear hug by a bright faced girl, who said, “My dear little new mother,” so warmly that she loved her on the spot, as well as the manly youth who laughingly took her next, pleading, “Me, too.” “And this Is my husband, Ralph,” the girl explained as another young man step- ped forward. *“And this, Janet, Harry's wife.”" Then & nurse moved forward into the circle, holding a bulky armful. “And this, mother,” continued the girl proudly, “is your little granddaughter.” 8o these were the “children” who need- ed her. - The second Mrs. Mallory swept the group with an eye that sought her per- fidious husband. He had disappeared. Then she buried her convulsed face in the soft, sweet smelling bundle contain- ing her new grandchild to smother her (Copyright, 1903, by T. C. McClure.) LLYN HARDIN was a man who, though but 37, had traveled till he was well wearled with the world. Without family or ties, no one cared when he came nor where he went, so that, whenever he did think of settling down, it was with a very decided picture in his mind. A picture of a home that was home in the fullest of the word, where there reigned a wife whose life would be bound up in that home; where there romped little children who would ‘welcome him with smiles, and with droop- ing faces see him go. And it was this feeling, but AQully realized, that made him look upen Miss Ellison with some- thing of doubt, albelt much of admira- tion. % Life was joyous to Allce Hjlison. Her blood ran high and nothing had crossed her path that tended to make her feel aught but the joy of lving. It was nat- ural, therefore, that she should laugh and dance and sing. Bometimes, though, it palled on her and she would sit within the silence of her room, wondering why she could not “fall in love, really and truly and deeply.”” And always at this wonder the picture of Allyn Hardin rose before - - “Miss Foster appeared.” “Alice! Miss Ellison—"' Jaughter. < e e ——— —- - 'L‘ TS ——* By F. B. Wright. I_"_‘"'— = —— (Copyright, 103, by T. C. McClure.) g—3 FOUND the old man in his favorite place, a grassy nook on the mountain side, gazing across the lake to where the opposite mountains rose from the water's edge. Darrel had a great store of wisdom— not the wisdom of towns, but the lore 9t the woods, of the snow-born streams and the mountains. His voice was as soothing as the wind through the great pines, or the rush of the river through its gorges. “It was twenty vears ago tifjt Mary came here with her father, old man Drury. He took up a claim down to the end of the lake. Mary was just a little DANGERS OF THE DEEP By Ruth Edwards. 2 He jumped down into the trim little sloop, and began to take the covers off the salls. He whistled softly to himself; and the girl on the dock watched him, her blue eyes shining through her long wet locks. With a cheerful hum and clatter of rigging, the white sall ran up the mast and swung to and fro on the ‘wooden boom. *“Want to come?” said Morris suddenly to the girl on the dock. “Oh, may I? Do you really want me she cried. “Sure!” said the laconic Morris. Out they danced into the sparkle of bright waves. The wind swept the girl's hair from her face in a long shining banner, She fang to herself, too happy to talk. Occasionally her eyes met Biily's as he sat contentedly at the helm, and were met by an answering smile. He liked her silent good-fellowship. She didn't alk you to death the way most girls did. @ whistled an accompaniment to her gay song. “It is awfully good of you to take me along like this,” she sald at last. “Espe- cially when I know your opinion of girls as a race. The boys told us what you sald when they broke the news of our arrival to you.” *Oh—oh—did they? I beg your pardon,” stammered Morris, “Oh, don't apologize, I understand how you felt,” sald his companion laughing. “We are In the way, I know.” “It girls were all llke you I wouldn't care how often I found them in my way,” remarked Morris boldly. “Was the fishing good yesterday?”’ she inquired wickedly. ‘You seemed so in- terested in it.” Morris blushed. “Oh, come now, don’t rub it in. T see what I missed all right.” “We were dreadfully hurt,” she went on in mock sadness. ‘“We tried to think it was unintentional, but the boys speed- fly set our minds at rest oft that score.” “You must have thought me a regular boor. What can I do to prove to you that I'm sorry?” Morris asked, waxing tender in the sunlight of her mischievous emile. His companion was evidently practical. “I know. Let me steer for a while,” she sald eagerly. « “Why, sure!” he answered, and gave his place at the heim, he, the self-elected P : : gal then, that I could take on my knees, an’ play with an’ teach to fish, an’ pad- dle a canoe. An’ year by year she growed and growed,,pretty as some flower put down here in a crevige of the rocks. "An then one day—I mind it well—I seed she was a woman an’' that I loved her. Thar wasn't neveg no spring like that spring, nor no day l‘(e that day. “I didn't tell her so—I was feared al- most to touch her, 1 was so rough an’ rude an' she so like a flower, but I thought on her a heap. It didn’t make no difference whar 1 was, layin’ out on the mountain side with only the stars for roof, workin’ in the shaft or settin’ in my shack listenin’ to the wind howling through the timber an’ the crackling of the fire, Mary was everywhar. She was in the first siar that came shining out at night, in the first flowers that sprung up in the bottom lands. The voice of the river in the shallow places was like her laughter.” The old man pointed a sinewy finger down toward a clump of trees below us. “It was thar on that point, with the river on one side and the lake on the other, that I built my house, setting up here of an evening. It was to be a real house—not a log shack—an’ vines all over it, an’ a garden. Many a night I've bullt that house, an’ lived in it, an’ watched Mary rockin’ the cradle. I used to travel, too, them nights, me an’ Mary, to the East an’ far off kentries what she’d read about. “Jim used to wonder why T left him an’ come out here by myself, but it was be- cause 1 wanted to be alone an’ think about it all. I never told him nothin’ of how I felt. g “An' then one evening I went down to Mary's house for to tell her. It were gettin' dark, as it might be this very evening. I landed quiet an’ came up the path, an’ then 1 knowed what I might bave knowed all along, for Jim an’ Mary was settin’ lookin’ at the sunset—an’ each other—an’ 1 knowed they loved each other an' that was nigh ten years ago. “I had forgot that I was old an' rough, an’' she was young, an' that it was as natural for her to love Jim as flowers to love the sun, but I didn’t think of that then. I was wild like as I paddled away up the lake an' climbed the trail to the shack an' sat thar in the dark cursin’ him. God forgive me. “He come home by and by, did Jim. I could hear him whistling way down the mountain side as if he was happy. He sat in the doorway, lookin’ up at the stars an' taikin’ about the claim we had, an’ if the mine panned out, an' of the money we'd get for our red cedar logs. An’' then he said, shy-like, as if 'twas something wonderful, ‘What do you think, Jack,’ says he, * going to be married soon— to—to Mary,’ he says. “It was after Jim had quit an’ gone to bed an’ I reaming abroad through the dark that I felt it. All night I tramped through the timber, thinkin’ an’ fightin’ with the wild beast in me. I had loved her first. Thar was plenty other women for him to be happy with. What right had he with his good looks and youth to come between us—he, my pardner, to steal the flawer I had watched and tended. “I was crazy that night—plumb crazy. Along toward day 1 come down the moun- tain straight as a stream for the cabin, an’ with my mind made up. I would kill him whar he was. He should never have Mary -as for me, I warn't thinkin’ about myself. I went into the shack an’ found my hunting knife. Jim was lyin’ in his bunk, the faint light from the window on his face, an’ he was smilin’. Once I tried to send the knife down an’ falled, an’ skipper, never known before to relinquish “twice I tried, but again the strength in the tiller to any human being. He showed her how to steady the course over the sunny soun She was an apt pupil and laughed gleeftilly as they met the waves. Morris, watching her, resolved that he ‘would breakfast at the big house if suf- ficlently urged. ‘When Seaton and Holbrook came down to the dock some time later for their dip they held their breath in astonishment at beholding the sloop heeling over to the breeze, a girl at the tiller, while the cyn- ical Billy sat beside her and dried her hair with a Turkish towel. “Gee whiz!” exclaimed Holbrook, *“will you look"at that? If there isn’t Billy jol- lying the chaperon!” my arm seemed to give out. I stood thar lookin' down at him, an’ then I flung the knife away an’ came out here an’ watched the dawn come up over the mountains an’ the mist roll offer the lake, an’ thought of all that Jim had been to me—an’ of Mary. It was natural she should love him an’ not me. Me! I was right old enough to be her father, let alone bein' rough and ill-fayored. As for Jim—how was he to know that I cared, or if he did know, he couldn’t help lovin’ whar nature told him to. Like to like. Youth to youth, who could help lovin® Jim—or Mary. “I wrastled it out here with the sun comin’ up a glory over the mountains, an’ at last I seen how foolish I had beén. an’ knowed it was Mary's happiness I wanted —an’ Jim's. “They was married an’ lived here for a while, until Mary's little gal died, an’ then she couldn’t seem to bear the place, an’ Jim took her East—him an’ me, for what I had was his'n. L get a letter onct in a while. They're happy an’ doin’ well.” Darrel pointed to a vine-covered boulder nearby on which there was cut a rude cross. “After little Mary died—so pretty, so tiny—I brung her here in my arms, an’ laid here thar—Mary cryin’ beside me— an’ now I love to come here an’ set after the day's work is done. No, I couldn’t go East. I couldn’t leave her,” he sald simply. The blush had died from the sky. The crests of the mountains shone out cold and white. The night had come—but it was a night radiant with the light of myriads of stars. *+ her, and her heart grew tender. And then something would crop up like weeds in the parable, choking out these tiny seeds of love. And that something was piti- fully like the vision that had but j,:llt ut the clear blue ey - mouth so firmly set with determination, the chin so square that she would rise impatiently, crying out: “‘Ah, no, he would never be tender, nor sweet, nor—nor—"" For she, too, had her plcture of what a home should be, and while she scarcely dared dwell on it, as he could do, it was there, in the clouds above her head. A home in which there was a woman whose lite’s one alm was to keep the tired lines from her husband's face, the worrying cares from his heart, to maintain forever .the smiles on those little upturned faces at her knee. But the husband must be one with a heart warm enough to take and profit by the sympathy she held out to him in such good abundange, a man who could understand the hearts of those little children, in the arms of that woman. 8o, thinking much but understanding little of each other, they went their sepa- rate ways, until one morning early, when a train drew out from the depot, Alice seated in the chair-car, Allyn swinging on to the step of ghe last coach. He was off on his vacation, and in the curlings of the smoke he saw not the face of Alice Ellison, but cool, green nooks by running streams. He heard the crunch of the dried leaves beneath his feet, and lllell the tugging of the trout upon his ne. He had bld Alice good-by two evenings before, expecting to leave the city then, and he recalled her look of good, frank friendship, as she had put her hand in his. “What a pity there is not more to her,” he mused; “she is so attractive, but he lacks weight. The train was coming to a stop, and Allyn rose and went out on the platform. They were slowing into a picturesque lit- tle town, with green trees in sight of the depot, and big, sprawly southern homes, white and green in the sunlight. Was that Alice? Yes, there on the lower step of the coach ahead of him she stood, with an impatience barely hidden by her qulet manner, waiting for the traln to stop. She was smiling, oh, so brightly, and the train had scarcely come to a stan still before she had sprung down and was running across the platform to meet— Allyn Hardin could not believe his own eyes. A little girl, with brown legs flashing bare above low socks, and face, left bare by the bonnet that hung about her neck, reflecting the brightness he had seen on Alice's, came rushing down the platform, too. With a shriek 'of joy, she threw her- self into Alice’s open arms. The whistle blew again. Alice was mov- kg ¢ kcwnd they lved each other.” ——— e +CUI}’SID Louise H. Guyol. - ing off with a young man and woman who had foined her. pi “Miss Ellison! How do you do? Alice turned about quickly. “Oh!" she gasped. “I thought you were in Wisconsin.” She moved toward the train_not losing hold of the little hand that lay in hers. “I coyld not get off. you were aboard”—the tr “Good-by, good-by." “Bon voyage!" called Alice. ing toward the child, “Wave by-by Mr. Hardin." A sumburnt little hand clawed the air, and Alice, raising her head, looked up at Allyn. They both laughed. On the rest of that north-bound trip all that Allyn saw was a little country raflroad station, with its usual motly setting. Standing forth from it all were the same two figures, the Madonna and the child—one in gown of soitly clinging blue, the other in ruffied white apron. The two weeks' visit to her bfother came to an end, and the train was fast drawng Alice Elllson away from the sweet peace of the country into the rush and whirl of that old life in the city. Leaning back in her chair dreamily looking out of the window, she came to the conclu- sion that she was tired of herself. She sighed and rose wearily. Swaying with the motion of the car, she made her way toward the Pullmans. It was Octo- ber; perhaps she might find some of her friends returning to the city. Pausing a moment on the threshold of the sleeper, she looked down the red-plush aisle. A few feet in front of her a man was geated, with his back turned toward her. He had light hair, “just like Mr. Har- din's,” and standing on the seat beside him was a little child. The car lurched, and the little fellow swayed, only to be caught by a strong arm that threw him downward; then the man's head darted down and Alice smiled at the screams ot childish laughter, She watched them for a moment, then the child, peering over the man’'s shoul- der, called out, “Pretty lady, pretty lady!” and she, feeling too weary to more than smile at the little fellow, turned to go back to her uninteresting book. The train was crossing the long bridge over Lake Ponchartrain, and Alice paused in the vestibule between the Pullman and the chalr car. Standing at the window she looked out upon the, vastness of the moonlit lake and sky and felt very tired and small and useless. She was not blue, nor was she morbid: but, somehow, her heart rebelled at going back to that old life in the city, so empty. so shallow, so— Wish I had known in was moving. Then, bend- to “Alice! Miss Ellison—" “Why—why—where did you come from?* Her voice trembled, but she did not care. She held out both hands to Allyn Hardin, and as his own closed over hers a sudden picture flashed before her. She heard again those peals of childish laugh- ter, saw again a man’s head bend swiftly down, like a great boy’s, beneath the tug of baby's hands; saw a face, habitually cold, alight with something divinely warm as it had looked at her across the sunny head of Jittle Alice, from the narrow doorway of a fast receding train. Her heart gave a bound that frightened her, and, drawing her hands away. she turned and ‘looked again upom the moonlit water. “I was called home unexpectedly on business,” Allyn was explaining, when he noted that she was not listening. He stepped nearer to her side. “Miss Ellison,” he began, then he saw how the moonlight was caught and shim- mered In the tears that lay on her cheek, and which she could not help any more than she could have told the reason why they fell. “What's the matter, Alice?” There was a long pause, and when she answered her volce was like a tired child’s. “Nothing. Only I'm so tired.” She had turned and, Involuntarily, stretched forth her hands again, but Allyn‘'s hands slipped past her’'s, and he folded her in his arms. “Oh, Alice,” he murmured; “Alice, you don’t know how I love you.” She raised her wet face to his, and as he bent low over her the weight slipped from her heart, and the old life, that had so tired her, became a thing of the past A STUDY IN HEREDITY | Fable for the Foolish. ] +. e — — HE male portion of the human race above 4 years of age Is di- vided into two parts, those who remember the days of their youth with pleasure touched with regret —that they are gone—and those who have substituted an abridged edition of ‘the Rollo books for their youthful memories. The former seldom have any children of their own and are pointed out to the off- spring of other men as sad examples of an illspent youth; the latter are usually pillars in the church and shining speci- mens of good citizenship. It is of & gen- tleman who belongs in the latter class that we propose to unfold a few well and carefully chosen thoughts. Solomon P. Eogy was the gentleman's name; if you hadn’t known it you could probably have guessed it on the first trial. In his old age this highly respect- alle person was all that any could have wished, and a whole lct more than some people liked, but we deeply regret to state that when he was younger he was not only a boy but also one of the boys, which is a very different propesition. They treasure his memory yet in the lit- tle old town where ha was wont to infect the. atmosphere and on extra dark nights they bring it out to assist the villaga street-lighting department. It was con- fidently expected that he would be hanged before he was 30 years old, and the life insurance company that would have con- sidered him a desirable risk would” bave cenvicted itself in the eyes of the popu- lace of imbecility in- the first degree. However, it fell out in the course of time and inhuman events of one sort and another that Solomon contracted a case of chronic matrimony and put all his other evil ways far behind him. Some men take the Keeley cure and some try matrimony; it all depends on the temper- ament—and the wife. In fact, some try matrimony first and the Keeley cure af- terward. As a result of Mr. Fogy’'s mat- rimonial experiment a young Solomon soon appeared on the scene. This event marked a definite stage in the career of Mr. Fogy; hitherto, as has been carefully hinted, he had put in the greater part df his time increasing the acreage of wild oats and otherwise adding to the cares of the recording angel. From this time forth, however, he could have posed as the model for a young ladies’ boarding school without turning a hair. But all this was past and by way of be- ing forgotten when young Solomon regis- tered in the Maison de Fogy. It would never do, argued Solomon S8r., for the stald father of a family to be seen in the company of the insidious and enervating cocktall that walketh by noonday or of the exhilarating but equally deadly high- ball that fiyeth by night. So he cut it out and set up in business as general guide, counselor and friend of the young and erring. There is nothing that so quali- fles a man to point out the way of life to the perishing as to have perished a little himself in his youth. Thus it was that Solomon Sr. exchanged the spirituous for the spiritual and became in his declin- ing years—declining because that was what he always did now whenever he met any of his old but unregenerate friends—a pillar of the church and one of the prineipal props of an otherwise lop- sided soclal system. As young Solomon grew to manhood he began to display tendencies that filled his father’s heart with sorrow, mixed with anger. He had never been allowed to mingle in any soclal gathering more ex- citing than the giddy whirl of the straw- berry festival at the Methodist church or to indulge in any beverage more stim- ulating than the common or garden birch beer. Yet, in spite of his father's fre- quent injunctions to assoclate only with people who could do him good, ne be- gan to be found in the company of dis- solute youths who foregathered with strong drink when it was raging and could look a full house in the face without bat- ting an eye. When his father remon- strated with him for his’ waywardness he replied that he was obeying the paternal injunction to be found only with those who could do him good. The ambiguous nature of this exceeding soft answer was not revealed to the stern parent until he discovered the exact extent to which his offspring had been done. It happened that about the time that the injured father was seriously contem- plating the advisability of severing dip- lomatic relations with his erring offspring the said injured father paid a visit to the town of his birth. It will be remem- bered that he had departed from the same town several years prior on what was confidently declared by the best au- thorities to be a through ticket to the gallows. When he returned after many years clad in the full garb of respecta- bility and propriety and bearing upon his manly brow the marks of a virtuous and prosperous life there was great wonder- ing among the oldest inhabitants, and by way of making him feel good they forth- with began to recount his youthful ex- ploits. As Solomon Sr. sat by and heard them tell over the many reasons for the belief that he could never by any possi- bility come to the end of his days in a peaceable and orderly manner he did a little wondering himself. In fact, it took him some time to recognize his own youth in the guise in which it was kindly pre- sented for his edification by these friends of his youth. Little by little, however, it broke in upon his darkened Intellect that his own memory of his early days was abbut as near like the real thing as a Government weather report is to being an accurate forecast of the article that Jupiter Pluvius and the rest of the crowd are proposing to serve up for the delectation of the sons of men on the fol- lowing day. Phii AT Y\ S ‘“His father remonstrated with him.” The last blow came when one old gray- beard, who ought to have been preparing for a safe passage across the river Styx instead of indulging in sinful recollections of a dissolute past, told him that Sglomon Jr. was an exact image of what Solomon Sr. and his accomplices had been in their bold, bad past. This remark set the old man to doing a little high-class recoliect- ing on his own account. with the result that he came to the conelusion that the best way to reform & boy is to begin with his father about twenty years prior to the boy’'s birth. As has probably been guessed already by the good guessers, the boy made the riffle all right in the course of time and without any particular help from the old man. When the hot blood n his veins had cooled a trifle he saw the error of his ways and settled down to assist his paternal ancestor in propping up the ex- isting state of society. At last accounts he was one of the most substantial and popular props in the business. The general conclusion to be drawn from this highly edifying and otherwise useful tale of real life s to the effect that there is a general tendency In the sci- entific world for ¢hips to bear a close re- semblance to the old block and that the best way to rid a boy of his bad habits 1s to let him wear them out. (Copyright, 133, by Albert Britt.)