The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, October 11, 1903, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

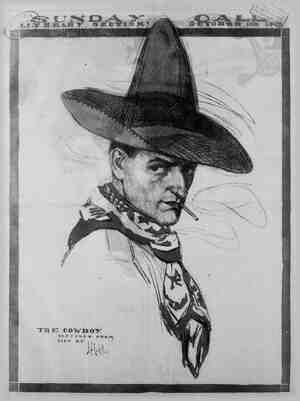

- I VERY LATEST LITERARY NOVELTIES & right, 1903, by T. C. McClure.) MULL ve! R ERMAN E thir B very musical and was The very much in love fect that he was very shy and very much in irbed sturbed other the on the bale ways cheered of his beloved “fiddle” - he knowledge that spring was com- n the spring that he fell in blonde, untidy looking tcllow who so ad- her irst sight. But Herman was a handsome fellow, despite the careless manner in which he dressed, and the new stenographer often glanced at him ap- provingly when she knew he was looking ther way. Drummond, the senior partner in introduced Herman to the new He knew Herman's repu- rmess, and only by a great >wn a smile when he saw lush conspicuously upon glance of the young tion over, Herman his books, more for g the blush die away other reason. As he pored ks he reflected with delight Helen Dumont, was ss hours were 1 the violin and f e companionship on the e balcony that he decided he was at ast in love. Then he took the violin to his confidence, cuddling it up to his ery softly a little love mtry, It was a sunshiny, and his feelings. He i ielen was musical. She be, her face was Eo sensitive, he decided As he played he heard a window raised e next door and reflected un- some o© would probably to him to keep his fiddle the daytime. Howeyer, no st came, and he changed the air he playing to Schubert's Serenade. had he taken up the.measurs n he heard a voice acco ing him No words were sung: it s a gort of humming, but in a voice of so pure a soprano quality that he was thrilled through and through. Then he played one of Sauer's peasant love songs, and the voice still accompanied him, this time singing the words very softly But other windows in his own house were "PLOT FOR THE STORY By M. J. T | by T. C. McClure) ideal June morning. A chorus of bird songs at aroused Cartright B w toric ancestor, who illed his food with a » the grass was still wet ed & passion for ugh the dew. He dressed refused to come at Cart- g. With an instinctive e magazine's style, he had rincipal characters of is st be two—a man and a er must be fine and sin orable, & gen ev ., who had made & place in the world by his own efforts. The girl must be sweet and true, with softly curling r, and wide, frank, innocent blue eyes. honor the world apart, b ve s, as if alone rness, cried each unto other. F: ng the drip- ping hat to its owner. She was the 1 of his story per He had ima is heroine wit ! bout her temples, j s did and she knew him for a 1 they were seated side by like 0ld friends. ed that her name was Ruth and that she was visiting at Miss Broadhurst knew ght, had read some of his ries ung man's character and chievements had been highly spoken of Lawtons, and although the y of their meeting at first tro lack of a formal introduction ceased to make itself felt That will ever be a golden afternoon in . ght's memory. At times he read from the book of poems with which Broadhurst had planned to while an hour alone by the river. More en they chatted of many things—plays And then long silences would fall, silence more eloquent than words, in which each seemed to read the other's unspoken thought. It was wonderful to the girl, this perfect sympathy and companionship with & man whom she had not seen until e few hours before. Two little clouds oc- casionally darkened Cartright’s sunshine; he was plighted to another, and on Miss Broadhurst’s slender, pink tipped third finger & splendid diamond flashed. He banished these thoughts whenever they came. “This one afternoon shall be ours,” he sald to himself. Quite naturally he fell to talking of his story and the plot that would not come. “The man is an athlete, a splendid fel- low in every way. Him I have modeled after Philip Lotridge, & friend of mine at college. He has won his way up from the ranks, bas my hero, and he is worthy of gny woman living, even the one my imagination has created for him. He has been abroad, and I've fitted him up with some of the experiences I had myself while reporting on a New York paper. But he is doomed to lose her. The Turks say, you know, ‘He that has many horses hath no wives.’ I've endowed him with money and graces of body and mind, but 1 cannot give him the girl he loves, “And she, Miss Broadhurst, if I can picture her as I see her, should make me famous. 1 thought one so sweet and charming could not exist, until I saw you, &nd you are her counterpart.” It was no idle compliment, no silly at- tempt fiirtation. Swiftly the girl gearched Cartright's mind and found him sincere. ““Thank you, Mr. Cartright,” sh said stmply,, yet she colored with pleas- ure. “It may seem queer,” he continued, “but there is & feeling, too strong to be overcome, that I must part them. I would give all I have, could they but marry; vet they cannot. It is what I call my literary comsclence. Often I know that my stories would sell better were 1 to change In some cases even & single paragraph. But I never do it.” sha s A 5. it ik it 9 97 SRIDE BV} Phillips. ——p His companion nodded. “I know the feelilng. When I was a little girl my er gave me the task of sweeping the 1 did not like it, and at first I did it hurriedly, leaving unswept the places I thought would not be discovered. When mother came to inspect the room her tone of mingled *reproof and surprise filled me h shame when she sald, ‘And my Ruth did not sweep behind the door!” all, yet whe or dc That was ver I am tempted to shirk, anything which is not right I think, sweep behind the door." naive simplicity delighted Cart- and he led her to talk of her home her friends and her daily occupa- Yet tr was never a word of the ring, nor the man who had placed it ipon her finger, and Cartright respected he fine delicacy of her nature. Everything must come to an end, and incomparable day was drawing to a close. With a start of surprise the girl noted the slanting sun. “I had no idea it was so late,” she said. “How the time has flown.” Cartright helped her to her feet, every nerve thrilling at the touch of her little hand H held it between his own, and bent uously toward her. eed we say said. “May I not call to- ler eyes to his. They wers troubled at his words, yet epths was an appeal he ld not mistake—an appeal to his chiv- “It must be good-by,” she said, om, * 50 am L” he replied, suppose after the 12th of ptember I must not even think of you any more.” the 12th? Why, that is r. Cartwright, there is the plot story.” be written?” he asked pas- . pleadingly. “That story is so the saddest I have ever known.” e sweet lips were tremulous, but the eyes were brave and steady now. “It must be written,” she said softly. “Your heroine was true and sweet. Help her to ‘sweep behind the door,’ to remain true to herself and her promise. And oh, believe me! Though they parted, those two in the story, she always remembered him, and,” breathlessly, Was sorry, per- haps, that—that they were not to be to- gether, nor even to see each other again.” “And he—the man In the story—was more than sorry. He would have said much, yet honor forbade. She gave him a rose which he always kept. And that is the end of the story.” The girl unpinned a rose at her breast. She kissed it and handed it to Cartright, and went her way unseeingly, for her eyes were fllled with tears. She turned once and looked back. He stood upon the spot where they had parted. The rose he held to his lips. 3 "HE HAD SECURED v:a.“msslon TO _SIT Ol 'THE FIRE-ESCAPE INTHE EVENINGS AND P HIS LA STy THE SUNDAY CALL. lo raised to protest at the music. From the window where the singer sat a silvery laugh floated out. The window closed and the voice accompanied his music no more that night. Next day at the office he stole many furtive glances at Miss Dumont and tried to decide whether he was in love with her or with the volce he had heard the night before—already he was beginning to think of it as The Voice, mentally cap- {talizing the words. Before the day was over he decided that he was in love with Helen Dumont. The graceful turn of her head and the, purity of expression in her big brown eyes seemed to him worth all the volces in the world. But in the even- ing The Voice again accompanied his violin playing and, for an hour, he was near to forgetting Miss Dumont. This went on al§ through the spring and Herman began to lose flesh uhder the strain of trying to decide whether he was in love with a beautiful girl or beautiful voice. Time and again wrestled unavalling with the shyness which prevented him from getting better acquainted with Helen Dumont. He often met her on his way home In the evening and knew that she lived somewhere close, but he could never quite get his courage up to the point of asking permission to call on her. Then he made up his mind that he would see the owner of The Volce. He knew that she lived in the house next to the place where he boarded, but & pro- jecting bay window cut off the view of this house from his window and he had no way of knowing what room the owner of The Voice occupled. One evening in June he made his op- portunity. At the end of a walts song which he had been playing, he softly laid down his violin and stepped on to the next armed fire-escape balcony. He was long armed and athletic, so it was with little difficulty that he worked his way along from one fire-escape to another un- til he had rounded the point of the bay e ara |V SUNDAY CALL’S HALF HOUR ‘STORIETTES -1- & window. The bright moonlight mnda"‘ easily visible on the fire-escape knew that he stood an excellent chance of being shot for a burglar, but physical danger was not half so terrifying as the prospect of continuing longer Wwith his love divided between a voice and a woman. As he reached the point of the bay window he peeped cautiously around it He saw a girl leaning out of & window and he instantly darted back. The girl was Helen Dumont. He had not known she Hved so close to him and he hoped she had seen him. He resolved to it where he was until the girl wit he Voice dow. He ! before he I refrain o been playing a few minutes befors. Again peeping cautiously around the wall he again saw o Helen Dumont. She saw him and laughed that sweet, silvery laugh he had heard before. It struck him suddenly and very for- cibly that he was a fool, a big German, musical, sentimental fool. The owner of The Voice was Helen Dumont. There- fore, he m be t s as much in lo with Helen as he had thought it possib to love a woman. Very quistly he made his way back to his own balcony and picked up his violin again, If, stupld fool that he was, he could not speak for him- self, he could make his instrument speak for him. The Voice was silent, but he did not care. He knew that she must understand. As a finale he played a com- position of his own and retreated within his .own window only in time to escape epithets hurled at him from balf a dozen nearby houses. And, once having told his love with the violin, he had less difficulty than he an- ticipated when he called on Helen Du- mont the following evening and proposed in due form. Mr. and Mrs. Herman Muller live in one of New York's prettiest suburbs in & cottage where violin music and singing can disturb no neighbors. The wife is just as happy as a woman can be whe takes vast pride in her husband's talent and stupidity; she is prouder even of his stupidity than of his talent. Herman— well, he has never gotten over falling In love with his fe twice, a thing possible only to stupidity like his. LEES’ LEGAL WOOING By John Barton Oxford. (Copyright, 18, by T. C. McClure) c——3 EE blotted the closely written page and pushed back his chair from the dainty desk before which he had been writing. He daid this that he might feast his eyes on the profile of the young woman who sat beside the big, red-shaded lamp, her brown head bent over some snowy linen in & diminu- tive embroldery frame. The room in which they sat was large and low-celled. It was, moreover, & homelike,~ comfortable sort of place. There were etchings on the walls, skin rugs on the polished floor, bits of dainty bric-a-brac on the mantel and desk; on the great hearth a little blaze sputtered cheerfully, bidding gay deflance to the raindrops which rattied against the win- dows. Lee thought of his own bare shack on the side of Bald Mountain—its rough in- terior; the clutter of papers and caps and spurs on his desk; the walls devoid of or- nament save maps and advertising prints; the floors long unswept, and the smell of old Jose's rather erratic cook- ing filling every nook and corner. As he contrasted his abode with this room he sighed, and at the sound the young wo- man glanced up quickly from her work. “Completed?’ she asked with a smile. “Yes,” he sald, “after a fashion—a rather original fashion, I fear, in the eyes of the law. I trust, however,” he added, with & laugh, “it won't be carried into court. Here it 1s.” He picked up the page before him and read aloud: “An agreement entered into on this, the twenty-firft day of March, A. D. 1301, by and betwsen John G. Lee of Santa Maria, County of El Placido, party of the first part, and Elizabeth M. Towne of Santa Maria, County of El Placido, party of the second part, witnesseth: “Party of the first part agrees to cultl- wvate the vineyard of the party of the sec- ond part for the period of one year; all laborers, implements and irrigation to be furnished by party of the first part; party of the first part to harvest the yleld and to dispose of such yleld in such manner @s seems me advantageous at the time of harvesting. “Party of the first part further agrees to pay to party of the second part one- half of the gross income thus derived; payment to be made to party of the sec- ond part upon receipt of money by the party of the first part. “Witness my hand and seal, “JOHN G. LEE, “Party of the First Part.” “If it's all right, you might sign beside my name,” he sald. “The document is perfectly satisfactory At itself,” she explained, “but really, it ¥ THE GRAMMAR OF LOVE---BY S. MARIE TALBOT. -# (Copyright, 1908, by T. C. McClure.) one at the ball last night, Priscilla.” *‘Oh, Dan!” “Hanged ‘wasn't, Pet!” Priscilla puther hands over her ears and re- peated the words “you wasn't” with out. raged grammatical scorn. ““The deuce! It's that old language busi- ness again, is it, Pris? I can't break off old habits—not even the eternal one of loving you, wife!” Somewhat mollified by the tender tone of his words, Priscilla put on her trim riding habit and was adjusting her hat before the glass when Dan called up from the lower hall: “‘Oh, Priscilla! Were it you who took my gloves from the hat rack?” Priscilla’s reply, “It was not,” was of 80 severe and stately a character that Dan down below shivered with silent glee; while up above the mirror reflected to his wife & coumtenance over the judftial sternness of which a smile flickered like summer lightning. They were soqn cantering down the beautiful hedge-lined country lanes, Dan's dog, Rev, bounding along behind. “Will ‘we go by Jackson's lane, Pris, or across the Glen pasture?” “Will we go?”’ echoed the girl. “Dan, your grammar will kill me yet.” ‘“What's up now, Priscilla?” Dan, blandly. “It is ‘up’ to you, Dan, to use your ‘shalls’ and ‘wills’ properly.” ‘Great Scott!” groaned her husband. “She uses slang! Ignoring the interruption, his wife per- sisted: “You should say, “Shall we go down it you inquired gisie o — -~ 2k tha ik " Jackson's lane? “I ses, Priscillal You shall go down Jackson's lane whether you will or not.” “Dan, you are simply absurd,” half- laughed, half-pouted his mentor, who was & bride just from Boston and doted on “language”’—such language s shuddered at the trenching of final letters upon the initial ones of the word following, and to whom Italian “‘a’” was fetish, and the un- defiled use of the futures a cult. Dan’s childish associations had been more with negro servants than with grammarians, all owing to the death of his mother and the indolent irresponsi- bility of his father. He was unable to the habits of speech of a lifetime en thought lightly of th ‘scru- pulosity”” of expression of the few Yan- kees he had known. He fell in love with Priscilla “head over heels—boots and all,” as he expressed It, when she came on a visit to an aunt of his, living near his own ancestral home. That he had been able to win the girl's heart showed that love laughs at gram- mars as well as at locksmiths. Bhe thought so trivial a matter as his wverbal {naccuracies could be easily mend- ed, and he believed that what to him was her puritanical primness of language would soon give way before the breezy ease and untrammeled freedom of manner and speech of his beloved South, disdain- ful of cramping rules and technical for- malities. In short, he was an educated man, iIn whom carelessness of expression was ingrained, yet whose vital and vig- orous ideas were wont to put to rout his wife’s vallant onslaughts in the line of rule and model. His wife would attack him with Rus- kin, to which he would listen with an im- patience only kept within bounds by his love for her. “Listen, Dan, to what he says: ‘A well- educated gentleman may not know many languages—may have read very few PO e B il el books. But whatever language he knows, he knows precisely; whatever word he pronounces he pronounces rightly; above all, he is learned in the peerage of words; knows the words of true descent and an- clent blood at a glance from the words of modern canaille: remembers all their ancestry, their intermarriages, distant re- lationship and offices they heid in any th an@in any country.’ Now, isn’t that fine, Dan?’ pleaded Priscilla. ‘And while this man of ‘words’ was tracing up their peerage his bosom friend was stealing away the heart of his wife and the foundations of his* home were crumbling beneath his feet. I don't know the ancestry of many words; but there is one that is of my own descent. It is the womd ‘Honor.’ You will always hear me speak that plainly with the true Carrol accent, in our home, for myself, for you and for the children who may be ours, please God.” “Oh, Dan,” whispered his wife softly, and they discussed grammar no more that day. Nevertheless when they were cantering along together Priscllla’s ears were keen to mark what was sald amiss by her husband, emboldened by his ever chival- rous patience with her grammatical ex- cursions. “I feel like I am the happlest man slive to-day, Priscilla.” “Incorrect use of ‘like,’” broke in his wife, knowing better, but disregarding the finer instinct. “But, Pris, I don't feel ‘as if'—it’s ‘like,’ that I feel. And now that I think of it! I don't feel like I was the happlest man alive. Have I corrected myself?"” Priscilla knew she was venturing too far. But when do we ever follow our strongest leadings? % 5 “Dan, if you love me as you say you do you would take more pains to speak correctly. Your ‘shalls’ and ‘wills’ put in right would make me sleep better A e nights. And your ‘shoulds’ and ‘woulds,’ if they would fall into line and keep step, my bliss would be complete!” All of & sudden, to their startled vision, appeared around a turn of the narrow hill road a team tearing with break-neck speed down the steep way up which their horses were climbing, and on which it ‘was impossible to pass them. The driver was thrown out as they rounded the curve and could be seen stryggling up from a pile of rocks upon which he had been hurled far below, in the ravine which skirted the road. The carriage was bounding violently from side to side. The two women and child in the back seat were at the mercy of the terrified horses, that were madly running directly toward Priscllla and Dan. Another moment and they would be upon them. At the foot of the hill was a rocky fora waiting to engulf the fated occupants of the vehicle if they should reach it alive, Paralyzed by fear, Priscilla knew in a maze of terror that Dan sprang from his horse, throwing her the bridle. Then she saw him, through a fear dim- med haze, rush just in time for the sal- vation of them all straight In front of the maddened brutes, with arms out- stretched to stop them. She heard his masterful command, ‘“Whoa, boys! ‘Whoa!" ::uho made a dash for their go sprang nimbly from side to side to avold being trampled under their hoofs. Again and again it seemed that their brute strength would overwhelm him as they plunged forward stralning to get free. The man and the beasts strove, it seem- ed to Priscilla eternal ages—until at last! —at last he was conquering them. With mouths dripping bloody foam, eyes start- ing from their sockets, they ly stood trembling, but still, save for an occa- sional trampling and champing of -their - 2 bits. This, too, ceased at Dan’s command: ‘““Whoa, boys! BSteady, boys!™ Their brute Instinct responded to the master without fear. He stood at length stroking their manes, Even then Priscilla realized in a dim unworded way a thing that was better than the subjection of signs and symbols to rule and law. She emerged from her crucible of agony with an aching ‘rellef that her husband was alive, while her own soul, shriveled by the refining fire, saw him with a larg- er vision, a deeper understanding. Proudly he 'marked his chivalrous bearing toward the unnerved, frightened women, who lauded his exploit in words of intensest gratitude. She noted with a swelling heart his bluff kindness toward the bruilsed and distressed driver, who came limping up to see the extent of the calamity, bloody and battered from his terrible fall. He made light of what he had done, calling it “nothing.” When the trembling animals were quite pacified, greatly to Priscilla’s\ap- prehension her husband turned the vehicle around about—a thing not done without much ado on the narrow shelf of a road—got into the carriage and took the reins with a firm hand to drive the ladies to their home, which was “but a mile or so back,” they had told him. Priacilla led his horse for him until he could deposit his charges at their own door. “Your man is too knocked up to drive,” he tactfully explained, as he saw the ladies tremulous at the thought of being trusted again to their unlucky Jehu. % “Dan, you are simply great,” Priscilla told him as they rode down the hill again toward home. “I'm proud of you through and through. But promise me never—never—never again to take so an.amuntt. It makes me faint but seems to me to be utterly superfiucus You know I trust you fully.” “I am vastly flattered by your faith in me,” he sald earnestly. “Still, business is business. Tell me how jong it is since the vineyard has given you moderats re- turns?” “Not since my brother died, three years @go,” she sald. “The first year I hired Juan Velasquez as superintendent. I left at the end of the season and bov a vineyard of his own down the r It was my fault. I gave him full sw. Then last year, Jim Bartlett, the SBan Joachim vineyards across the mountalns, took it on shares. The yleld was very good, but not as good as Bart lett's ‘excuses. Velasquez did leave me a little money from an off year, but Bart- lett took all the money of a good year— and boasted about it, too.” “The cu sald Lee, hotly. “You see,” he went on, “that's just why I insist on this agreement. You've only known me since I bought out the vineyard on the mountain eight months ago. I may be a bigger villain than both the others com- bined.” “You differ materially from Velasques and Bartlett,” she sald. “Heaven send 1 do,” he said sincerely. She came over to the desk and picked up the pen. “If you'll feel better about it, I'll sign,™ she sald. “I certainly shall,” he asserted. “Very well, then,” she laughed, “only remember, I shall expect great things, and if you don’t make enough for me to afford a piano I shall have you in court.” “I'll make it pay as it never has be~ fore,” he sald earnestly. “That's just what I fear,” she said, lay« ing down the pen. “I'm afraid you won'y be honest—to yourself.” “Oh, I'll be honest enough to myself, never fear,” he said, and added in & lower N tone, “about the vineyard.” “I want you to be honest te yourself about everything,” she sald. “You muset be or I won’t sign the agreement.” “Well, I can’t be honest about the agreement.” “Why not?” “Well,” he sald, “if I drew up the agreement to honestly suit mywelf 1§ would suit the party of the second part far less than this one suits me.” “1 insist you draw it up that way,” she sald. “I can read It, and If it lan't satis- factory I needn’t sign.” ““You won't be angry or think me a foof it I do?" he asked. “Of course not,” she assured him. “Very well. You make some more leavey on that tray cloth and I'll wrestle with the Ink pot once more.” There was silence for several moments while Lee's pen traveled rapidly over the paper. At length he pushed back the chair again. “It is finished,” he sald, “and ready for your—your disapproval. I realize after & reading of this I shall be cast into outer darkness. And so before that sad event occurs I want to ask you to think as kindly of me as you can.” He picked up the paper and faced her with a quaint gesture of appeal. “An agreement entered Into this day by and between, and so forth. “Witnesseth: Party of the first party, being a solitary resident on the bleall slope of Bald Mountain, in a dismal shack very dreary and lonesome, and further, being subjected—thrice daily—to the cull- nary machinations of a pseudo-cook, one Jose by name; sald party of the first part knowing, moreover, a delightful place In the valley just below him. and being pos- sessed of an honest, sturdy, sincere affeo- tion for the owner thereof, who is the party of the second part; pagty of the first part agrees to love, honor and pro- tect party of the second part; to give her all the happiness In his power so long as they both do live, provided the party of the second part will accept party of the first party in the bonds of matrimony.” His volce ceased, and for several silent moment she regarded him steadily. It's hardly satisfactory,” she said, T knew It." hardly " she sald as eye: fell and her face flushed “because no mention Is made of the ‘homest, sturdy, sincere af- fection’ of the party of the second part. If—if you can insert that I'll sign.” @i @ to think of it. What if those awful run- away horses had killed " and shuddered. s - “Then you could, should have been a widow, Pr!sc"ll:’u Voo “I neither will, nor shall, no lh:uld ordwch!d be a widow. rl_fim;-li; whep-¥ou do, Dan,” sob! —r bed Priscilla hys- “Never say die, little girl. We will be happy; nothing shall Pfl.cllh‘!" Pprevent it, my “You 'are a hero, Dan!” The sirk reached out her hand to him, and in their clasp thrilled between husband and wife the love that is above and by~ language, yond all speech and