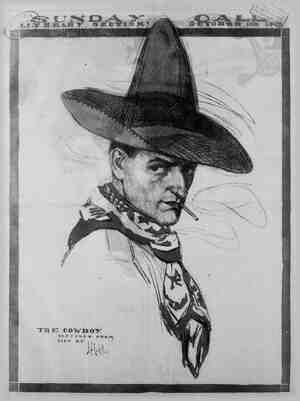

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, October 11, 1903, Page 2

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

CTYEIS is the fourth and last in- stallment of “Lees and Leaven,” which is E. W. Townsend’s latest work, and a book that has de a remarkable impression, a to be read and reread. ext Sunday, following the Sun- Call's Literary policy of giving aders the best and most absorb- ovels of the day, “The Golden ” will be published. The name ne ie something to conjure with. watch for this story after read- installment. ure, Phillips & Co. and horror- the fallen man “It's htened ent over ttered & plteous ery Paxton!” Is 1t asked the officer uneas- recognized the n e. short time ago that he had in bis favorite e, daily, Turnbull!” exclaimed the glad you happened along ? y men, I seems to have a cut to ring up an ambu- TI'm a ing get to heil out of here with him,™ cer said, noticing a ma near. The stranger was attitude of the three " the body, fallen, mo- “What 1s 1t?” he said e dully reflecting & near 10t seeing the face, her officer, who the street. “And so witnesses over on the co! u t make no holler about a police | was not listening. “Poor boy! y he whispered, as he rested s hea x on his arm. for a quick,” he said, ran to the corner bad to be properly dressed 6 surge sald after a brief ex- n. “Have you sent in an ambu- he esked of the police. mbulance,” Turnbull said sharp- ulance cases are news storiea. sust not get into the newspapers.” ught was of Grace. ty police officer sighed with re- ere was a reason, he did not know e what, why Turnbull did not want T own; that me that he a newspaper ‘‘roasting, ject of that treatment, “roasting’’ was done experience the officer cassured, he took a friendly man- Make room too curious air.” 10! the sur- Decide quick ere 15 to be taken Harry with the car- s £ it to ke him y in the bull said, as he lift Howard into the was up, sewing, when Harry t nto the room and frightened he looked so wild. ‘Howard Paxton!” he cried. “From my old home. He was al- - se. Hurry, Bessie! The be The d s com S the m olly gan to quiet him, but the g & bruised nce of two men ca s that Tur could not. He head aside, weaker than Bes- work, the surgeon began his when ssle was a quick-witted assistant a P e prepared the bed »ed the surgeon 1 . X ere another room? Can I go gomewhere &lse—near by—until—for & lit- tle? Turnbull asked of Harry. Harry sald, drawing him ner room, where he lighted the o a little bent figure rose £e ur ed in a corner and asked in a 1r ned tone, “What's the matter, He 1 stared, to find the figure in g at him. o work “Aren’t you one of in the office?” he s, Mr. Turnbull.” en what in the name of heaven are you doing here?” she's my sister,” Harry whispered. She's r. You know me. You've ten it me—8miling Harry. Paxton. He always helped me at school.” Varry was in a frenzy of excitement and kept repeating over and over, “We were boys together; he helped Harry at school.” But Turnbull had forgotten him, the staring figure on the bed. even where he was, in the eagerness with which he lis- tened for sounds he dreaded, to hear from ~ Dext Toom. “Find out for me at least if the man is #'ive or dead,” he whispered hoarsely to skt “He's alive,” said Harry. when he re- turned to Turnbull. “They shaved the hair away and the doctor's stitching, and Bessie—" “Don’t tell me those things, yeu hound!” moaned Turnbull. “Have you been say- ing that you knew Mr. Paxton? How the devil Aid you ever know him?” “Alwaysi Always!” Harry orled, eager to free his mind on this important sub- ject. “I'm from his home, too I'm Harry Lambert. I slways knew him. He was niger to me than any one else. Helped me with arithmetic and history.” But Turnbull was again listening for any sounds from the front room, other han the quiet even voice of the surgeon, ecting Besste. got a paper with his father’s name his mind te Does does a m father’s, I could sh to him end the po- startling u know & r. Turnkt deed? hat was h r is dead? Eb if it's any goc t told.” cried too, lice were) “Listen n? Turnbull “Did he o is 1t?" whispered Nora. “Harry, tell me, who 1s in there?” Paxton. Howard Paxton. I know whispered Nora. the gentleman who gave me the money the night I wouldn’t have had the rent, and when we had the nice dinner. That was his, too—the money for that.” “Was 1t?” asked Harry, quick tears coming to his eyes. “He was always bet- ter, kinder than other men to me.” He turned again to Turnbull. “Would I have to go to court If I gave Howard the pa- per I've kept all this time?” “What paper?’ asked Turnbull, but so sharply that Harry was frightened and only eald, “I never meant to keep it. If it's any good to him he can have it. Is a deed val -t The doctor stepped to the door and m to Turnbull. Bessle had quickly leared away all traces of the dreadful —the blessed work!—and Howard, his head neatly bandaged, lay on the bed, still unconscious. “It's & bad scalp laceration only, sa far as the superficial wound itself goes,” the surgeon said, “but there are some symp- toms of concussion of the b Can he be moved from he urnbull asked “Yes; better now than later—and he should be. T s no place for him.” Turnbull called to Harr “Get into the carriage we came in and go to this a dress as fast as can. Don't ¢ ut the gentieman—Y eorge Bannister.” “I'll hurry,” answered Harry excitedly, changing his apron for an old overcoat; one too old and torn and stained.to be pawned “Can’t the doctor do something for Harry's cuts first?” asked Bessie timid There were a number of scratches on the sea-foo the sur- geon quickly ssed. stop- ping in his work to examine curious'y old dimple-Jike scar on Harry's cheek Then Har ke w hurried be a alr and be gone surgeon n ambulance—one elt Hospital in time there id Turnbull. “Go to any You are very thoughtful.” The surgeon went away, and Turnbull sat by the bedside, murmuring: *Poor Who I8 to tell her? If T hed only with him In time!” He w of his troubled thougt ly: “Will H messenger to ride in off that sta ut Bessie asking tea into trouble with the police over The doctor sald it was a police wound.” “Harry?’ repeated Turnbull vaguely, not removing his fixed gaze from How- ard’s face. “Harry, my hus—the sea-food man, who helped you. Turnbull glanced about the roon, “We shall not trouble the police—the vermin!— about this. There's no trouble for Harry there.” She was sitting on a trunk, he on the only chair. The bed and a small cookstove completed the room's furn‘ture. ‘Will you take this for the heip Harry been to us?” and he gave her a ten- r bin “I've often heard Harry speak of Mr. Paxton as the only boy friend he had in the West, where he was to school. I wouldn’t take it,” she added, weeping softly, “only that we are 8o poor now.” The surgeon returned, saying that an ambulance was at the door, and a minute later Harry came back, with George Ban- nister. The latter was white and trem- bling with rage—he had forced the true story of the brutal attack from Harry— and his torrent of anathemas was 0 unceasing, so picturesque, so baleful, that the surgeon more than once looked up from his careful preparations to move Howard to glance at the young man in surprise. Although the Bannister family had re- turned to thelr city home for the winter, George kept and lived in his handsome bachelor apartments. There Howard was taken, unconscious, but none the worse for the trip, the surgeon said. He watch- ed over Howard, resting in Geogge's bed, while the others talked softly in an ad- joining room, and just before daylight reported that Howard had recovered con- sclousness and was in a favorable cop- dition. but was not to be disturbed until club XLwE M N the surgeon returned which he promised to do at noon. Turnbull told George that he had been at work in his office until nearly mid- night, and tben had gome to the office of the paper on which Howard was em- ed to. ses him about some work he had found for him. He learned that How- ard was out on a murder story, and he 1) was on his way to the police ., where he expected to find How- learn where he was, when he m n his pitiable piight. " cried George. ‘‘The Sloux! The th T'll find the murderer who struck Howard and kill him. My father himself shall prosecute the ruffian. The hroat!” of the kind,” Turpbull said ing weari n the first place we couldn't get a witness, Even that half-witted sea- food man would not dare tg testify to what he knows. . And do we want Howard's sister to read the story? She must know nothing 1f we can prevent {t."” He was silent while George fumed and fretted and swore; making frequent tip- toe trips to the bed room, and at last busying himself putting away Howard's clothing, which had been hastily thrown about the room. He gathered up a num- ber ngs fallen from the pockets, among them a letter addressed to Grace. “That’s the trouble on his mind,” George said, throwing the letter to Turnbull. “The poor fellow is muttering her name, over and o in his sleep.” Turnbuil took the letter, laid it on the table before him, and looked at it a long time before giving it to George to return to Howard's pocket. It was a letter Howard wrote to his slster just before he started out on the story, intending to post 1t. “From Tu something 1 said, heard to-dav,” as he gave the letter to his companion, “I've a strong impression that Paxton reveals in that letter facts about his affairs which he has tried to conceal from his sister. If it is o, I hope it necd never be sent. I had good news to tell him about some of his work—that's why T followed him.” It was not stran that Turnbull, with his intimate knowledge of Howard's af- fairs and his svmpathetic perceptiong s ened by his feelings for Grace, had 50 close conjecture as to the con- tents of the letter. Perhaps, had he read it, he would bave known better than an- other, the heart-ache, the brulsed prida, the stormy half-dazed mind, with which the letter written in its brave at- tempt to conceal the truh—yet tell 1t! s was the letter: ‘Dear Grace—I shall certainly punish you severely—as dear old dad used to say when we'd worried him to his wits’ end, but never got the punishment we de- rved—if you breathe another anxious cath aboyt me. I am all right, dear, nd we are all right. I'm as lion hearted as a lion and never doubt that I'll come bright side up with a smile. Now, after that boastul language, 1 feel like a hang- man to have to write in this same letter I cagnot send a red cent this week. Whew! perhaps it doesn't rasp a fellow’s pride to have to say that sort of a thing for the first time. But as it I the cheer- ful truth and as there's no earthly way out of telling it—why, there you are! But don’t you be anxlous for old ‘Paxy,’ 1 was known in football days to your youthful rage. Remember? I never was @ g@r at running around the ends, but at bucking the center, when we simply had to make a gain, ‘Paxy,’ you may re- call, was not without hard earned Kudos. “‘Of course I've done a lot of cheerful Iving to vou ahout my affalrs, but you must forglve that, bacause I had the best of excuses—I thought I wouldn't be found out. I've taken a reporter's place on the highly ornate, but low sal- arfed, paper whose letter head I'm using, but it's only a stop-gap. Turn- bull has been & trump in showing me the ropes, and under his advice I've filled up the offices of a dozen week- lies and monthlies with short storles, poems, jokes—oh, but I'm a joker!—and about every description of literary ware. But one must wait for aeceeptance—or rejection—and then most of them pay only when the matter is printed. So I must wait and in the meantime make confes- sion of my bankruptcy. Just keep your pretty upper lp firm and your dimpie in full play, and no one will be the wiser. Of course Turnbull knows, but he is too experienced to make my position harder by offering help. George, I've managed to keep in ignorance, I think, for if he guessed, he’d pawn his last possession and offer me a loan! Perhaps George guspects that I'm not buying bonds to any great extent for he's strangely soll- citous about my dinners these days. I have to accept more invitations to dine with him than I want to under the eir- cumstances, in very fear that, if I decline, he’ll guess the truth. He says that his people enjoyed very much having you over with them Thanksgiving, and that they are going back to the country over the holidays and we are to be asked. You must go, Grace, not only because you will have a good time, but for the sake of THE SUNDAY CALL, appearances. Make my excuses again and tell Madge any fib you think of to keép her from guessing why I'm such a bad correspondent these days. Also do not be alarmed if 1 don't call on my regular days, for my duties here may require a quick jurmp out of town any time. There! In & rambling way I've made my confes- slon. But it's not a confession of faliure. Not much! Play ball! Lovingly, “HOWARD.” Turnbull was writjng at the table. “We must send some ‘sort of word to Miss Paxton,” he sald, as George continued his visits to the bedroom, his tramping about the parlor, his uninterrupted mut- terings. “Precious small store of gold and silver about Howard's pockets,” he sald, “so far as I have discovered. I've a notion now, Turnbull, that he was harder pushed than any of us knew. Brass-plated im- becile that I am! not to have guessed the whole truth instead of the half. Here am I, a scribbler of doggerel, a town crier, making more money than is good for me while he—oh, if I'd only known!" “And cut the man's heart out with an offer of help!” muttered Turnbull, who was still writing. When he' finished, he showed this letter to eGorge: “Dear Miss Paxton: “If a man will pursue the delights of a reporter's life he must some time pursue them out of town, and on short notice, as perhaps your brother may have told you. Howard had no time to write to you— he ran me out of breath on the way to the train—but he asked me to attend to a matter he'd overlooked and I do so by sending you for him the fifty dollars you'll find enclosed. I think that his as- signment is a sensational lot of ship- wrecks up at the end of Cape Cod, so do not expect to hear from him for several days. I heard at the office that rafl- road tracks and wires are all down in that interesting but stormy land. It I did understand him as to the amount, be good enough to let me ow if your holiday plans require another remittance, as I have oth- er funds belonging to Howard. Sincerely yours, VID TURNBULL.” “Well, you're a cheerful and artistic Har,” George said. XVII-A MAN'S FACE IN THE LIGHT. Howard's letter tells as much as needs be told about his experiences in ‘the early days of his struggles to earn a living in a field injured for him by his connection with the Chronicle. Howard lied to Grace, swore that his temporary difficulty was not nearly as great as she imagined, laughed at her fears, and managed to send the board money and sometimes something more, though he went witRout dinner to do so. But Grace was not wholly ' begulled, though she never guessed half the truth; and now bent all her efforts to gaining an order from silk or wall paper makers. How much her mind was troubled nobody but one guessed. Jack Worthington di- vined more than even Miss Hartley. It had become his almost daily custom to meet Grace and her lively witted friend on their way home from the school and with the quick sympathy of a lover he saw that Grace was distressed; and he was utterly miserable that he could not offer aid—could not appear to know, even, the real cause of her growing sadness. But he loved her more. He determined to end his own suspense and then perhaps she could be brought to give him the priv- ilege of ending the cause of her unhappi- ness. This determination was very much in his thoughts when Mr. Bannister came to him one day and sald, “Jack, your father and mother will soon be home. What am I to tell your father is your determin- ation In the matter o. — “In the matter of a choice of a wife Jack interrupted, with a smile. “It is this: My cholce of a wife shall be my choice—if T am so fortunate as to be ac- cepted. You question me at a moment when I can give a definite answer. To- day 1 shail ask Miss Paxton to marry by “If that is your decision, God speed you!” the lawyer sald, and left the room. ‘When Jack had forced his way through the holiday crowds along Twenty-third street and across Sixth avenue, he did not make any pretense of not looking for Grace, but with eager eyes scanned the throng for her familiar figure. Now that he had resolved to know his fate he was almost feverishly anxious to realize his hopes or—but he would not admit doubt: she must love him because, surely the best of reasons, he loved her so much! He saw them approaching, walking more slowly than usual, Florence talking ear- nestly to Grace and he hastened to greet them. Grace was silent and he saw that she had been weeping. He looked from her tn Flarence heseechinely and the lat- ter, with a responsive glance at Jack, said, "I am going to shop; but Grace Paxton; who has & headache because she works all day and all night, and worries the rest of the time, is going as straight home as ever was.” She gave Jack an- other look as if saying, “and you are go- ing home with her.” She avolded Grace's detaining hand, hurried ahead a few steps, turned, and sald, “Mamma Is to meet me, %o you two go home and have tea together,” and rushed on Into the crowd. They walked on for a time In silence, close together, so as not to be separated by the surging crowd; and then, dfter glancing at her sad face with a love in his own eyes which she saw, and sometimes met with her own eyes, steadi- Iy, sometimes drooped her eyes before, he said to her gravely, “Will you not tell me why you are unhappy?’ Her eyes met his agailn, wistfully, as if it would be a reilef to tell him eéverything, but she did not speak and he added, “Because I love you very much and want to comfort you if 1 can, to sympathize with you, to help you—because I love you very much!" He had forgotten every one of the thou- sand phrases he had thought of to tell his love; forgotten the time, place, cir- cumstance he had Imagined would mo favor his declaration, and in the solitu of the crowd, unmindful of the world that pressed them close side by side—or else would part them—he seemed to be alone with her, and in homely words which he had not numbered among all those he had rehearsed, he told her over and over he loved her. 3 no, no!” sheswhispered, “you must I am unhappy! I am unhappy!” Yot because 1 say I love you?" N0, no, ne! You must not!” Something in her voice exalted the young man. The crowd, with its thou- sand interests, the busy, the idle, the hunted, swept and surged about them, few seeing, none caring, though some may have mused a moment on one group of the passing picture, & young man, with exylting eyes, close guarding a young woman whose eyes were downcast, and filled with tears—but not wholly sorrow- you tell me what makes you un- In Mrs. Hartley’s little parlor she ald tell him. Howard had gone out of town, the night before, she said. That morning she had received a letter from a news- paper friend of his, containing a message from Howard. But the letter was de- signed to keep from her some misfortune of Howard's. It was meant to deceive her, she had felt sure, as soon as she read it. Why? Yes, she would tell him all—because it contained a sum of money, as if coming from Howard, which she did not. believe Howard could have sent. Her fears aroused, she had gone at once t. Howard's bachelor apartment. She w: told that Howard had not lived there for months, although he always called there for malil He had done that, Grace then knew to keep up the decep- tion, and this letter was a part of the same decelt. Her heart was utterly miserable. She had been a burden, In- stead of a help, to her brother: and If she had not been blindly seifish, thinking only of her own plans, never of his, she would have discovered the truth befors, and gone to him and shared his poverty, per- haps helped to make it less hard; anyway been by his side to encourage him, instead of burdening him with her selfishness and extravagance—and she was very misera- ble. Now, Howard was always being ship- wrecked and she did not even know where his room was, to go there at once, and Iive near him and share his lot, whataver it was: and be there to welcome him when he returned from his shipwrecks. And she was very miserable and it had been a relief to her to tell her troubles and she wanted a man’s advice and perhaps Mr. ‘Worthington could advise her. He wanted to advise her to let him help Howard. He recalled their talk once about the false pride of those who would not take help from even those who cared for them and wanted to help them. FHe ventured: “'Can we not arrange some plan for me to help Howard until”—he began, but stopped for the look in her eyes. She did not say anything, perhaps she could not speak, for the hurt he had given her. But he saw, without one word be- ing said, that his advice could not take the shape of an offer of the kind help he would have gladly extended to Howard; that if he did not want to imperil his own chance of recelving the word he longed to hear Grace speak, he must respect the pride for her brother he saw shining In her eyes. “May I see the letter you re- ceived?" he asked. Bhe showed him the letter. Tt had been written with overmuch artfulness to de- celve her, but Jack, reading it, sald, “Surely this is not so hopeless; Howard is not in the difficulty you fear. Turnbull must know.” “He 1is trying to decelve me about Howard, because he—" 'She stopped ith a blush. thington looked up quickly from the letter. “F se he loves yo he sald ““Oh, ne he cried. “Because he knows Howard's first thought is always of me!" “I will see T said Jack, “and robull, learn what I can.” “And find out where Howard’'s room is, 80 that I can move into one near his and be there when he returns.” “And I will come there for you." “For me?" “To take you away as my wife.” “I have not sald that I will marry you.” “But you willl" “No. I shall live with" Howard and study and work—design—and help him.” “Howard will be a successtul, busy man and won’t want you around him.” “You are a successful, busy man.” “I agree to try to be one when you are my wife.” “I1 haven't said that I love you.” “You do.” ““How do you know?" CRuse you haven’'t sald that you de no! It seemed only a minute or two later, but it was really an hour, when Grace :ud Florence and her mother are com- ng.” “May I tell them?" he asked “No. I haven't promised.” “Then I shall go,” he laughed, not at all in the manner of & man whose doubts had not been removed. When he had opened the parlor door, he turned back: “I'm going to the theater to-night with the Buntons. It's a theater party, and a long-standing engagement. If you care, I'll not go—have an {liness.” “Have a good time,” she laughed, and ran past him and up the stairs, colliding with Florence, coming down. “Turn around so that I can see your face in the light, young man,” Florence said to Jack, who walited for her at the front door. x congratulate you,” she added, after a llaf‘cs at his face. “I'm the happlest man in the world™ declared. ! R e “You look it,” was her comment. XVIII-DAISY BUNTON'S DISCOVERY. Jack Worthington econtinued to look happy as he sat in one of the boxes oc- cupied by the Bunton theater party that night. He sat by Daisy, who was very handsome, and looked so joyous that Qthers besides Isaac Bunton ascribed a sentimental reason for the elation of the young couple. ley were to return to the Bunton's for supper, and in the party's distribation Jack was to carry Daisy and Mr. Bunton In his own electric brougham, the others to follow in their several carriages. There was a crush at the exit, the passage to the carriages being half blocked by idlers. peddlers, newsboys, carrtage callers and pickpockets, whom the police at Intervals drove away. The men on the box of Jack’s brougham caught early sight of thelr master and made a quick approach to the theater front, and he, giving Dalsy his arm, started through the crowd, Mr. Bunton following close behind. A news- boy, @ lad with a lighted maten, making persistent offer of it, and a peddier, calling Plaintively, “Sea food! Sea food!" blocked the way. Jack felt Daisy start and trem- ble, and thinking she had been :ostled by the peddlers, he thrust out a vigorous arm to clear the path. The movement turned the sea-food man around, until Lis smil- ing face, scarred by a number of fresh scratches, came full under the glaring electric light. “Don't push me,” he wailed. “Sea food! Sea food!" Dalsy sank, so that Jack had to support her. He motioned to the footman who stood by the open door of the brougham, and the man quickly helped his master lift Daisy into the vehicle. “Come Mr Bunton,” called Jack nervously. Ther Was no response nor was Mr. Bunton in sight. He hesitated. Other drivers were noisily demanding the right of way, and the rest of the party had gone to the end of the block for their carriages. “To the Buntons'—and hurry!” he sald to the footman, and entered the brougham. He pressed a button that flooded the interior with electric light, and saw that Daisy was motionless and seemingly uncon. scious. He had not reached his age—this conspicuously rich New Yorker—without having had some experiences which made him now consider for a moment if this could be a vulgar device, but abandoned the thought, seeing that the sirl's usuvally high-colored face was deadly white and that she was scarcely breathing. Then he became deeply concerned—alarmed. It was but a short trip to the Buntons he thought thankfully, and took the girl's cold bands and chafed them vigorously They had nearly reached the house when she opened her eyes, stared at him, moaned, and closed them again.