The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, March 22, 1903, Page 3

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

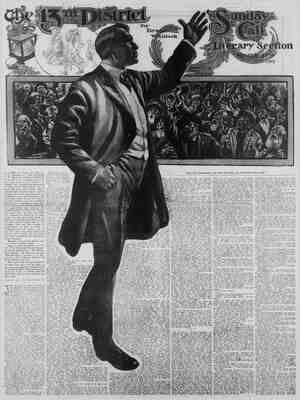

) THY SUNDAY CALL.. was in the forty-t .. Was I not, Colonei ihe torty-fourth,” corrected the col- d Congress witn sely o be sure, the forty-fourt very fine I formed a He was very high a fine man,” sald Gar- v in hus ofiice.” He was a very good him. We sat on the sgether. Did he ave a good practic . “OR, yes, the best at the Grand Praitie ar. He was the best jury lawyer we “3er had there “Yes, he was a good speaker: teach in the party credted by cullarly strong character heaied at ueath? “Well, it's pretty much healed now; fer @ long time it bothered us, but we never bear of it any more.” retty pupuwar with the people, Was the his pe his was ery.” would presume so.” The great man closed his eyes as if shutting in same im- Garwood went ntion of his name LOW. , indeed,” said the candidate. sed a pegiment about there, daid on, *“the bare will set them wild “He he Yes—the old Ninety-third—the Bloody Ninety-third they cailed it. A number ¢ his old soldiers will be at your meeting afternoon.” The candidate reflected that most com- munities like to think that ments have been k Lut he did not say he train sped on, then Garwood heard stop, heard the cheers and cries of the rowas outside, heard the rich voice of andidate speaking, heard the restless u on again with while the little two shin- tracks dissolved into one disappearing nt of the perspective far behind. The cheers faded away and he tried to imag- ine the sensation of the man for whom «li this outcry was being made. The great man seemed to take it coolly encugh. Either such things had grown common to him, or he had trained himself Ly a long course of public life to appear if they had, for when he was not mak- s ‘on the rear platform or nds with little delegations that to go to the Lincoln ceting resting in his stateroom. lie was not well, Garwooq heard the col- onel explain to some one, and had to conserve his energies, though some athlete in training he seemed ° to rest and sleep between his exer- ¢ private car and as the train began te with familiar forms, men with whom he had battied in conventions for s, he had fled to the easier society he denser atmosphere of the smok- car, greeting countless friends from all over the district and dging the cam- paign work Garwood felt he should be himself. But the magnetism of his , the joy of being in a pres- n were courting in those days, a desire to feel to the ut- netion of riding in a private there. P in had reached Atlanta Hill, and its noise subsided. The engine no er vomited black masses of smoke, seemed to hold its breath s, with seemed swiftly spires and of Lawndale showed an in- t above the trees and then out on the e train sped on toward Lin- overcoat he h speech, for much as to tching col and &s the ff heavily and the'train oln Rankin appeared, hot e said to Garwood, “we're s have all been askin’ fer 2 asked s hat did vou em you w old ‘man; out of his sight; they Garwood, half o ell them?" here closeted he wouldn't.let y t's what I told em They heard the strains of a marching band and then a cheer arose. cheering as the en- gine slid on past the weather-beaten stu— d stopped, puffing importantly as knew how big a load it had bauled. then the candidate appeared and mid- in a cheer the crowd ceased, strick- into silence by the sight of him. He instant, pale and distinguish- o his cleanly chiseled facc, an impersonal smile, almost the same as a d he were unaccustomed to him, crewd, committees, even ps of the railway carriage, for n lrelped him vn if i not know how such things were and -might injure himself. Looking fully to his right and to his left, still impersonal smile on his face. ate set his patent leather boots ntered platform and then sigh- looked around over the crow was all confusion where they stood, but Rankin was already beside the candi- date, calling him “Mr. President” as he introGuced to him promiscuously men who had pressed forward grinning in a not al- together hopeless embarrassment. All this time the airman of the Logan County committee was fluttering about, striving to recall the orderly scheme of arrange- ment he had devised for the occasion. He Lad written it all out on a slip of paper the night before, having the carriages numbered and in a bracket set against each number the names of those who were to ride In that carriage, just as he had seen the thing done at a funeral. But row he found that he had left his slip of paper at home and he found that he had forgotten the arrangement as well, just &= 2 man in the cold hour of delivery for- gefs a speech he has written out and bur- dened his memory with. As the chairman turned this way and that several of his townsmen noticing the indecision and per- plexity written on his face, with the pit- less American sense of humor, mocking- ly proposed: “Thiee cheers for McBain!" As the crowd gave the cheers the chair- man became redder than ever and en- treated the driver of the first carriage to come closer. The driver drew his horses, whose talls he had been crimping for two weeks, nearer the curb and then the chairman turned toward the candidate and sald: “This way. Mr. President.” The candidate had been standing there smiling and giving both his hands to men @nd women and children that closed upon him and as the chairman looked toward bim he saw Garwood standing by his side. The chairman had forgotten Garwood. In fact he had not expected him until evening and he had no place for him in kis scheme. Rankin saw McBaln’s pre- dicament and promptly assuming an of- ficial relation to the affair gently urged their Presidential candidate toward the Before the candidate would move, how- ever, he looked about and sald: “Where's the colonel?” Then the small man In the modish blue clothes appeared from behind him and the candidate sighed as if in relief. They 2ll heiped him into the carriage and he smiled in gratitude. The colonel climbed into the front seat facing his chief. Then another traveling companion of the can- didate, a man who ‘was slated for a cab- inet position, followed him. Garwood seemed about to withdraw and had raised his hand to lift his hat when Rankin The crowd began i Garwood, there's to demur, knowing that no place had been reserved for him, but Rankin began to shove from bebind and Garwood found himself sit- ting in the game carriage with the Presi- dential candldate. The chairman, who tad expected to ride with the great guest Limself, scanned the line of carriages drawn up for the others in the party and hen slamming the door shut on them d te the drfire All right, Billy.” The drums rolled again and the band began to play. The captains of the march- ing clubs shouted their military orders and the carriage moved. Theé crowd cheered and the candidate turning, be- came suddenly grave. His pale face flushed siightly as with an easy, distin- gulshed air he lifted his high hat. Gurwood saw that Rankin had secured a seat in one of the carriages farther Lack in ihe line.and that half a dozen wspaper men, whom the local chairman failed to take into account, were standing with bored, insouciant expres- £l , waiting to be assigned to vehicles, realizing that the affair depended, for all Leyond a mere local success, upon their presence. At the last minute they were crowded into a hack in which some of the iocal leaders of the party had hoped to display their importance before their neighbors. The slight seemed a littie thing at the time, but it eventually creat- «d a factional fight in that county. The local chairman himself was compelled to mount beside the driver on one of the vehicles. Amid a crash of brass, the throb of drums and a great roar from human throats the procession wound up the crowded street. , All the way the side- walks were lined with people and all jthe way the candidate lifted his high hat with that distinguished gesture. The whoie county had come in from the country and farmers’ muddy wagons were hitched to every rack, their owners cling- ing to the-bridles of horses that reared a2nd piunged as the bands went by. One tewnship had sent a club of mounted farmers, who wore big hats and rode horses on whose hides were imprinted the marks of harness, and whose caparisons were of all descriptions from the yeilow peits of sheep to ican saddles, denot- ing a terrible scouring of the township Lefore daylight that morning. These men were stern and fierce and formed 4 sort of rude cavalry escort for the great man whom they cheered so hoarsely. The pro- cession did not go directly to the court- Louse, for that was only two blocks away, but made a slow and jolting progress along those streets that were decorated fcr the occasion. There were flags and bunting everywhere and numerous pic- tures of the candidate himseif, of vary- ing degrees of likeness to him and pic- tures, too, of his ‘“running mate’’ the ndidate for Vice President, who at that ninute was enjoying a similar ovation in scme far off Eastern village. Some of the honseholders, galled by the bitterness of purtisanship, flaunted in their windows pictures of the candldate’s rival, but the sreat man lifted his hat and bowed to them, clustered in silence before their residences, as impartially as he did to those of his own party. . In the last two blocks before the pro- cesslor reached the courthouse square they could hear a man speaking and Gar- waod knew'that the voice was the voic: of General Stager. The old courthouse standing in its ancient dignity in a park of oak trees, lifting its plastered columns with a suggestion of the calm of classic beauty, broke on their sight .and the music of the bands as they brayed into the square filled the whole area with the'r triumphant strains and cheer on cheer leapeds toward them. The music and the cheers drowned the voice of General Sta- ger and his audience suddenly left him @nd surged toward the approfiching pro- sion. The cheering was continuous, = candidate’s white head was bare most f the ttme and when the carriage stopped nd he was assisted up the stgps into the speakers’ stand the .hands ° exultantly rlayed “Union Forever, Hurrah, Boys, Hurrah!" the horns fairly singing the werds of the song. General Stager, red and drenched with perspiration, advanced to shake the hand of the Presidential candidate and the spectacle set the crowd yelling again. It was the same speech he had dellvered all along his itinerary, though his allusions 1o the splendid agricultural community in which he found himself, the good crops that had been ylelded to the hand of the husbandman, gave a fictitious local color nd his touching reference to his old friend, General Bancroft, by whose side he had at Washington through so many stir- ring years fraught with deeds and occa- s of such vast import to the national life and his glowing tribute to the Bloody Ninety-third brought the applause rolling Lp to him in great waves. He spoke for 1early an hour, standing at the railing with thé big flag hanging down before him and a big, white water pitcher stand- ing close beside; behind him were the vice presidents sitting with studied grav- ity; near by the reporters writing hurried- 1¥; before him and around him, under the green and motionless trees a_vast multi- tude, heads many of them bared, faces upturned, with brows knit to aid in con- centration, jaws working as they chewed on_their eternal tobacco. Out at the edges of the crowd a contin- ual movement shifted the masses and groups of men; along the curb were lines of wagons, with horses stamping and ewitching their tails; across the street on ihe three-storled brick biocks the flutter of flags and bunting. The oid courthouse, frowning somehow with the majesty of the law, formed a stately, solemn back- ground for it all; overhead was the sky, piling rapidly now with clouds. The whole square gave an effect of strange stillness, even with the volce of the speaker ring- ing through it; the crowd was silen:, treasuring his words for future repetition; treasuring perhaps the sight of him, the sensation of being in his actual presence, for the tale of future years. But suddenly, in a ‘second, when the crowd was held in the magic spell of his cratory, when men were least thinking of such a thing, he ceased to talk, the sgeech was over, the event was closed and the great man, not pausing even .ong enough to let the vice presidents of the meeting shake hands with him or t5 hear the Lincoln Glee Club sing a campaign song, looked about for the colonel, climb- ed out of the stand into his carriags and was whirled away, lifting his hat, still wiih that distinguished air, amia chcers that would not let the campaign song be- gin and with little boys swarming lika outrunners at his glistening wheels. ‘When the meeting was over Garwood went to the hotel to wait for Rankin, who had & mysterious but always purposeful way of disappearing at -times of such po- litical excitement as had been rocking Lincoln all that day. Garwood had long since learned when Rankin thus went un- der the political waters to await calmly his reappearance at the surface and so he wrote Rankin’s name and his own name on the blotted register of -he hotel and asked for a room. He had scarcely laid down the corroded pen the landlord found in a drawer when a voice beside him said: ““Did you see it yet, Jerry?"” Garwood turned to look in the grinning face of Julius Vogt, who had comsa over with the Grand irfe “‘excursion™ that morning. “See what?” asked Garwood. “Why,” saild Vogt, drawing something from his pocket, “Pusey’s articla about you—there,” and he ogened a copy of the News and gave it to Garwood. “Oh!" sald Garwood, “that!—I saw part of it.” And he smiled on Vogt, whom he felt Ifke striking. “Well,”” gald Vogt, still grinning, though tis grin was luun; something, “I jus’ thought, maybe—" “Thanks,” said Garwood. Several others of the Grand Prairie boys, as any one, considering them in their Wllflc&; capa- city, would have called them, had/drawn near, attracted by their candidate for Congress, whose wide hat rode above all the heads in the crowd. Doubtless they expected Garwood to open the paper, but he was too good a politician for that. As he stood there Ire {dly picked at the rag- ged edges of the sheets and when he spoke seemed to have forgotten it, for he how'd you like the speech?” * sald Bllly Feek. . “You bet” sald Doris Fox. “Didn’t he lam it into 'em?” sald Burr Ripplemann. 5till their eyes were on the paper, which Garwood seemed to be in danger of pick- ing_to pieces. “‘Yes, it was fine an effort as T ever heard under such circumstances.” He carelessly thrust the paper inio the side ocket of the black alpaca coat he wore. ‘he boys were sober faced again. “Gemn’ back with us tq-night, Jerry?” sald Elam Kirk. “We're goin’ to hold the train till after your speech. ““Reckon not.” Garwood replied. going over to Pekin in the mornin, looked at his watch. “Well!” he exclaim- ed, “it's nearly supper time and I haven't given a thought to what I'm going to say to—mghll.‘ b“ 1l you come and have a lit- tle drink before supper?” The boys grinned again, saying they didn't care if they did and foliowed Gar- wood toward the dingy barroom, making old jokes about drinking, in the manner of the smail town, the citizens of which, because of their- stricter moral enviren- ment, or perhaps of more otficious neigh- bors,.can_never induige in tppling with the freedom of city-bred fellows. Gar- wood could not escape without a joke at his expense, attenipted by some oneé of tha party whose appreciation of hospitality Was not refined, and though it made him shudder he had to join in the laugh it- provoked. But when he could get away from them at last he went to the roum e bad taken and there, seated on the edge of the bed, he opened rthe paper and keid it in the window to’ <n the fading light. It had been issued at noon that cay and given an added importance by the word “‘Extra!” prined in black and urgen. type at the head of its pige. Iut below Garwood read ancther word, a word that needed no buld type to mnake it black—"Boodler!”"—and tnen his own name. Pusey had adroitly chosen that day as the one most likely to'ald the effect ot his sensation and the opposing commit- tee had gladly undertaken to circulate hundreds of copies at the Lincoln rally. The article was obviously done by Pusey himself and he had taken a keen delight in the work. He had written it in the strain of one who performs a painful pub- lic duty, the strain in which a Judge, gladdened more and more by his own ut- terance, sentences a convicted criminal, though without the apology a Judge al- ways makes to ‘the subject of his dis- course in carefully differentiating his ot- ficial duty from his individual inclination. Garwood forced himself remorselessly to read it through to the very end and then abstractedly sitting there in the fad- ing light that straggled in from the dirty street outside he picked the paper into little pieces and sprinkled them on the floor. The letters of the headline were printed on his mind and as he sat there in the darkness and viewed the litter he bad made, seeing it all as the ruin of his Iife and hopes, he flung his great body neadlong on the bed and buried his face in_ his hands. » Half an,hour later Rankin thrust his head In at the door and called into the azrkness that filled the room: **Oh, Jerry!” He haltingly entered, plercing the gloom and dimly outlining the long form of bis candidate stretched on the frail bed. “Jerry! Jerry!” he said. Garwood's form was tall when it stood erect in the daylight; it was immense when it lay prone in the dark. There was sumething in the sight to strike a kind of superstitious terror to the heart and Rankin's elemental nature sensed some- thing of this, but when Garwood heaved and _gave a very human grunt Rankin cried In an approach to anger: “Aw, git up out o' that! Don’'t you kear the band tunin’ up outside?” The crowd in town had been gradually Gecreasing all through the waning after- noon; the multitude that had come to bear a candidate for the Presidency would not stay to listen to a candidate for Con- gress. With the falling of the night there had been a gathering of gray clouds and at the threatening of a storm the crowd thinned more and more. Gradually the weary ones withdrew, the howls of tipsy counirymen on the sides of the square subsided, the rural cavalry galloped out of town with parting yells for their can- didate, the square in the falling rain plis- tened under the electric light that bathed the ancient pediment of the courthouse with a modern radlance. At 9 o'clock Garwood finished his speech, ceremonious- Iy thanking and bldding good night a lit- tle mass of men who huddled with loyal partisanship around the bandstand, with a few extinguishing torches reeking un- der his nose, with the running colors of the flags and bunting staining the pine boards on which he rested his hands and with a few boys chasing each other with .sh“arp cries about the edges of the gath- ering. ‘VIL Ethan Harkness, having finished his la- bors, such as the labors of a bank pres- ident are, sat at his old walnut desk in the window of the First National Bank Wwaiting for Emily to come and drive him home. The old man had set his desk in order, with his big gold pen laid in the rack of his inkstand, his blotters held dowh_by a paper weight and a leat of Lis calendar torn off ready for the next day’s business. The desk was in sucn order as would have made the worktable of a professional man unfamiliar to him, but as he waited KEthan Harkness rear- ranged it again and again, absent-minded- ly, chauging the position of the blotters, wiping_his pen once more on his gray hair. Then he drew out his gold watch, aujusted his spectacles, took an observa- tion of the time and looked with an air ol incredibility into the street. Any break in the. routine of his life was a pain to Ethan Harkness and jt was with a res- ignation to this pain that he called: “‘Morton, bring me a paper! I might as well read it if I've got to walt,” The old teller, a white-haired, servile man with the stoop of a clerk in his shoulders and the disindividualized stare of a clerk in his submissive eyes, came shuffling .in with the paper he himseif bad been reading. Harkness took it re- luctantly. His life was as methodical as his calendar and If he read the evening paper before supper he would have noth- irg to do after, for he could not go to bed till 8 o'clock. If he he awoke too soon in the morning and then he would reach the bank before the mail had been delivered. Thus it will be imagined how serifous would be the train of con- Eequences set in mtion by one irregularity in his day. But he took the paper. It was the News and his eye lighted at once on the article that Pusey had written about Garwood. As he read it a great rage gathered in bis breast, a rage compounded of many emotions, which gradually took form, first as a hatred of Garwood for his misdeede, then of Pusey for laying them bare. Ethan Harkness was not a man of broad sympathies. What love he had was be- stowed on Emily; he had lavished it there ever since his wife had died. He gave 80 much to her that he had none left for others and he stood in the community as a hard man, just the man who had built ug his fortune by long years of la- bor and seif-denial that made him impa- tient of the fraiitie8 which his fellows in the little community, in common with their brothers in the wider world, found it so hard to govern and restrain. He sat there mute and implacable, with bis fist, still big from the farm work it had done in early life, clenched upon the News, while Morton clanked the bars of the vault in fastening the place of treas- ure-for the night and slipped here and there behind his wire cage, pretending little duties to keep him from facing his employer when in such a mood. It was after 5 o'clock when the surrey lurched Into the filthy gutter and when Harkness saw that Emily was not in it he felt his rn.ie with Garwood increase for depriving him thus of the pleasant hour to which he looked forward all the afternoon. He rode home in silence be- hind old Jasper, who tried in his com- panionable way by making his character- istic observations on men and things to draw his master out of his moody preoc- cupation. Harkness found his daughter at the sup- per table, and when he saw her he at once yearned toward her with a great wish to give her such comfort as a mother would have supplied; but with something of his own stern nature she held herself spiritually aloof, and he ate his cold meat, his fried potatoes, his peaches and cream and drank his tea without word from her, beyond some allusions to the heat of the sultry day, the prospect of rain and the need of it at his farm lying at the edge of town. Her face was white, but her eyes were rot red or swallen and she gave him no sign whether or not she knew of the blow that had been struck at the man she loved. He thought several times. of tell- ing her or asking her about it, but he was always half afraid of her and h submitted to her rule all the years when * the electric .light swinging an gfmone -else was strong enough to rule When supper was done she disappeared and as he suained his ears from s li- brary, where he was reading ail alone, he heard her close a door upstairs and leck it. Later, when he went up in his stocking teet, having left his boots down- slairs in the habit he had brought out of the poverty of his boyhood into the com- furt of his age, he paused a moment by her door and raised his hand as if to knock; but he could not figure it out, he said to himself, so he changed his mhd and went tg bed, leaving it all to time. When Emily went to her room she sat at her dressing table a moment looking at her own reflection until her features became so strange that a fear of insan- ity haunted her and then she half un- dressea and lay down upon her bed. She told herself that she could not sleep that light and yet after her first burst of tears sne fell into the sound and natural slumber of grief-stricken youth with its vague apologetic hope that the whitening bair will show in the morning. Far in the night she awoke with a strange ignorance o. time and place. She shivered with the chill of the night air. Rain was falllng and she heard tne lace curtains at the windows scraping in the wind against the. heavy leaves of a fern she was nurturing and with a woman’s Intujtive dread of the damage rain may do when windows are open she arose to close them. The cool air swept in upon her, -driving the fine mist of the raln, but she let it spray a moment upon her face, upon her grens( before she puiled her window down. Outside the yard liY in blackness and she looked down on it long enough to distinguish all. its familiar ob- Jects, each bush and shrub and tree; she saw the lawn mower stranded by the walk and she thought how her father would scold old Jasper in the morning; and tken she thought it strange and un- real that she couls think of such irrele- vant things at such a time. Yet every material thing w: ngreuslve:{ creaking at the corner of Ohio street with the ratn slanting across the ovoid of light that clung around it showed that; everything the same—vyet all changed with her. She turned from her window. The dark- ness {ndoors was kind, it seemed to hide the wound that had been dealt her and ste hastly undressed and got to bed, curling up like a little child. Then she lay and tried to think until her head ached. She had been thinking thus ever since the cruel moment that afternoon when she had picked up the News on the ‘veranda, Her heart had been light that day. She had thought of Jerome as he traveled in his private car with a coming President. She had gone with him to Lincoln and seen him riding through the crowdei streets; had beheld him in the flare of terches, his face alight with the inspira- tion of an orator, his eyes fine and spark- ling, as she had so often seen them blaz- ing with another passion; had heard his ringing voice and the cheers of the frantic people, massed in that remembered Equare. And so in the afternoon she be- came impatient for the cry the boy gave when he tossed the local papers on the flcor of the veranda. She had swooped down on them before the boy had turned his little back and mounted his wheel. And the thing that first struck her eye had smitten her heart still—the headlines bearing Garwood's name. She had caught at the newel pogt in the wide hall to keep from falling. It had not then occurred to her to doubt the truth of the tale Pusey had told. She had not yet progressed in politics or in life far enough to learn to take with the necessary grain of salt everything a news- paper prints. The very fact that a state- ment was in type impressed her as abun. dant proof of its truth, as it does chil- dren, young and old, a fact which has prolonged the life of many fables for cen- turies and will make others immortal. It seemed to her simply an inexorable thing and she turned this way and that in a vain effort to adjust the heavy load so that it might mcre easily be borne. But when*she found it becoming intolerable she began to seek some way of escaping it. In that hour of the night she first doubted its truth; her heart leaped, she gave a halt-smothered laugh. Then she willed that it be not true, she determined that it must not be true, and with a child-like trust in his emnipotence she prayed to God to make it untrue. And so she fell asleep at last. All these hours of the night, in a far humbler street of the town, in a small frame house where nothing could be beard but the ticking of an old brown Seth Thomas clock, a woman lay sleeping. Her scant, white hair was parted on her wrinkled brow, her long hands, hardened by the yenr,' of work, were folded on her breast and her face, dark and seamed as t was, wore a peaceful - smile, for she had fallen asleep thinking of her boy, laughing at his traducers and praying. pronouncing the words In earnest whis- pers that could have been heard far back in the kitchen, which she had set in shin- ing order, that her boy's enemies might be forgiven because they knew not what they did. VIIL ‘When Rankin came home from the Lin- ccln mass meeting he seemed to have reached that stage in the evolution of his eampaign when it was necessary to put forth mighty claims of victory. He de- clared that he had never had any doubt of ultimate success at the polls, though he admitted, with a vast wave of his arms to embody the whole magnanimity of his concession, that he had felt some- what disturbed by that apathy which was the result of over-confidence. But the meeting at Lincoln, he said, had complete- Iy dispelled these fears. He sald that the meeting at Lincoln had been a great out- pouring of the common people and that they had gone home so deeply enthusias- tic after the sight of their great leader that it was now only a question of major- ities. And as for Garwood, why, he had never been so proud of the boy in his life. The visit of the Presidential candidate would increase the normal majority of 2200 in the Thirteenth District to 3000, but Garwood was bound to run at least 500 ahead of the ticket. Rankin had publish- ed these views extensively as he sat .in the smoking car of the excursion train that {olled over from Lincoln the night of the big meeting. The Grand Prairle boys had been disturbed by the story printed in the News, but Rankin laughed at their lonr;. Just as he had laughed at Gar- wood. “Why, it'll do him .good!" Rankin de- clared, bringing his palm down on the knee of Joe Kerr, the secretary of the Polk County Central Committee. ‘Do him good, I tell you. It's worth a thousand votes to us in Polk alone to have that lit- tle cur spring his blackmallin’ scheme at this stage o' the campaign. It's as good as a certificate of moral character from the county court.” “Do you think it's a blackmailin’ scheme? asked Kerr. Eink {t!" cried Rankin, “why, damn it, man, I kn it—dldn’t you hear how Jerry threw rg out of his office the day he tried to hold him up? Why, he'd 'a’ killed him if I 'hadn’t held him back. You'd ou{ht to post up on the politicai history of your own times, Jo. The men who were perched on the arms and han \ng over the backs of the car seats, pitching dangerously with the lurches the train gave in the agony-of a bonded indebtedness that pointed to an early receivership, laughed above the groanings of the trucks beneath them. THey had gathered there for the delight it aiways gave them to hear Jim Rankin t:lk, a dellght that Rankin shared with them. § § “Wky didn’t you kill him, Jim?" one of them asked. ““Oh,” he saild with an affectation of modesty as he dropped his eyes and with his hand made moral protest, “I wanted him tc print his story first. T'll have to kill him some day, but I reckon I won't have time before election.” ‘While Rankin was extra nt in talk he calculated pretty accurately the effect of his words and never said ‘many things, in a pelitical '“E“ least, that came back to plague him. is conception of Pusey's motives was eagerly accepted by his own rarty men and they went home with a rew passion for work In the wards and townships. '\ ' Pusey meanwhile had been standing o street corners in Grand Praliris bis cane and glancing out with shifty eye from under his yellow straw hat, but men avoided him or when they spoke to him did sd with a pleasantry that was wholly feigned and always overdome, because tbey feared to antagonize him. Rankin had not seen him since the publication of bis screed, but one evening, going into tbe Cassell House, he saw the solled lit- tle edftor leaning against the counter of the cigar stand. The big man strode up to him and his red face and neck grew redder as he seized Pusey by the collar of his coat. “You_little snake!"” Rankin cried, so that all the men in the lobby crowded eagerly forward in the pleasant excite- ment the prospect of a fight still stirs in the bosoms of men. “I've got a notion to pull your head off and spat it up against that wall there!” He gave the little man a shake that jolted his straw hat down to his eyes. ““You just dare to print another line about us and you'll settle with me, you hear? Tl puil your head off—no, I'll pinch it off, and—"" Rankin, falling of words to.express his contempt, let go Pusey's coat and filliped directly under his nose, as if he were shooting a marble. Pusey glared at him with hatred in his eyes. “Dor’t hurt him, Jim,” one of the men in the crowd pleaded. They all laughed and Pusey's eye grew keener. “Well, I won't kill you this evenin',” relented Rankin, throwing to the floor the cigar he had half smoked, “I wouldn't want to embarrass the devil at a busy time like this.” . , The Chicago papers had not covered the Garwood story, as the newspaper phrase is, thcugh the Grand Prairie correspond- ents had giadly wired it t6 them. But the Advertiser, as’ well as one or two other papers in the Thirteenth District, which were opposed politically to Garwood, had not been able to resist the temptation to have a fling at him on its account, though with cautious reservations born more of a financial than a moral solvency. The Evening News with all the undimin- ished relish Pusey could find in any mor- sel of scandal, had continued to display its story day after day with what it boasted were additional detalils, but on the cay following the incident in the Cassell House Pusey left off abusing Garwood to abuse Rankin and smarting under Ran- kin’s. public humiliation of him injected into his attack all the venom of his-little nature. He Kkept, however, out of Ran- kin'’s way and all the while the big fel- low as he read the articles chuckled un- til his fat sides shook. Jim Rankin was the most popular man in Grand Prairie; men loved to boast for him that he had more friends than any three men in Polk County and the sym- pathy that came for Garwood out of a natural reaction from so much abuse was ircreased tod sworn fealty when Rankin was made the target for Pusey's poisoned shafts. When the story first appeared the men of Grand Prairie had gessiped about it with the smiling toleratfon men have for such things, but now it was a common thing to hear them declare that they would vote for Garwood just to show Fres Pusey that his opinions did not go for much in that community. Emily Harkness did not leave the house for days. She feit that she could not bear to go down town, where every one would see her; and there was nowhere else to go, save into the country, and .there no one who lives in the country ever thinks of going unless he has to. She had entrenched herself behind the idea that the story was untrue and she daily fortified this position as her only pessibie defense from despair, seeking es— cape from her reflections when they be- came too aggressive by adding to her in- terest in Garwood’'s campaign. She knew how much his election meant to him in every way and though she preferred to disassociate herself from the idea of its effect on her own destiny she quickly went to the politician's standpoint of viewing it now as a necessary vindication, ax if its result by the divine.force of a popular majority could disprove the as- sertions of Garwood's little enemy. Emily read all the papers breathlessly dreading a repetition of the story, but her heart grew lighter as she found no_ fur- ther reference to it. She had ordered the boy to stop delivering the News and she enjoyed a woman's sense of revenge in this action, believing that it would in scme way cripple Pusey's fortunes. She resolved, too, that her friends should cease to take the sheet, but she could not bring herself to make the first active step in this crusade. Meanwhile she had watched ‘for an in- dignant denial from Garwood himself, and she thought it strange that none appear- ed. But finally, striving to recall all she knew of men’s strange notlons of honor, and slowly marking out a course proper for one in Garwood’'s situation to pur- sve, she came to the belief that he was right in not dignifying the attack by his notice. She derived a deeper satisfaction wken the thought burst upon her one day, making her clasg her hands and lift them to her chin with a gasp of joy such as she had not known for days that the same bigh notion had kept him from writing to her, though her conception of a lover's duty in correspondence was the commom~ one, that Is, that he should write, if only a line, every day. But Garwood was busy, she knew, with his speaking en- gagements in Tazewell and Mason coun- ties and she tried faithfully to follow him on the little {tinerary he had drawn up for her, awaliting his coming home in the calm faith that he would set it all aright. IX. The strong-limbed girl who went strid- ing up the walk to the Harkness' porch ‘was the only intimate of her own sex that Emily had retained; perhaps she retained ker because Dade Emerson was away from Grand Prairie so much that custom could not stale this friendship. The girls had been reared side by side, they had gone to the same school and later, for a while, to the same college; and they had glowed over those secret passions of their young girihood just as they had wept When their lengihened petticoats com- pelled them to give up paper dolls. Dade Emerson, however, had never shared Emily’s love of study; she con- tormed more readily to the athletic type at that time coming into vogue. In the second year of Dade's college course old Mr. Emerson died and his widow, under the self-deluding plea that her grief could find solace only in other climes, resolved to spend In traveling the money with which her husband's death had dowered her. Dade Emerson entered upon the Lotel life of the wanderer with an en- thusiasm her black gowns could hardly conceal. They tried the South for her ‘mother’'s asthma and the North for her bay fever; they journeyed to California for the gooé the climate sure tow« do her lungs, and they crossed the Atlantic to take the baths at ‘Wiesbaden for her rheumatism. ‘While her mother devoted herseif to a querulous - celebration of her complaints Dade led what is known as the active out- door life. She learned to row and to swi she won a medal by her tennis playing and she developed a romping health that showed in the sparkle of her dark eye, in the flush of her brown cheek, in the swing of her full arm or the beau- tiful play of thej muscles In her strong shoulders as she'strode in her free and graceful way along the street or across the room. She climbed Mont Blanc; she withed .to try the Matterhorn, but the grave secretary of the Alpine Club denied ner permission when she dragged her breathless mother ur\ea summer up to Zer- matt to try for this distinction.. In the summer under notice her mother had declared that she must see Grand Prairie once more before she died and they had come home and thrown open the old hcuse for its first occupancy in two years. When the Emersons arrived ai Grand Prairle Dade had embraced Emily fervidly and the two giris had vowed that their old intimacy must Immediately be re-established on its anclent footing. With Ler objective interest in life Dade had no difficulty in glving her demeanor toward Emily the spontaneity it.is sometimes necessary to feign toward the friends of a bygone day and stage of development; and B0 she swung into the wide hall and falrly hl'nm:led Emily, who had come to meet her. “I've been just dying to see you, deah,” she sald, in the new accent she had ac- quired while in Europe, which was half Eastern, half English. She kissed Emily and flung herself into a chair in the parlor, whither Emily was already pointing the way. Her fre wholesome personality, her suminer g ments, the Very atmosphere of strengil and health she breathed were weicvine slimuiants to Emily. “It's sownright hot, I say,” Dade con tinued, wriggling until her skirts fluffed out all over the front of her chair anu showed the plaid hose above the low, Lroad-heeled shoes she wore. She gianced around io see if the windows were opeu Beastly!” she ejaculated. And tnes she took a handkerchief and polished her face until its clean tanned skin shone. 1 say,” she went on, tossing her hand- kerchief into her iap, ‘I dwn't slecp a wink thinking about you last night. I had to run ovah to see you abouc it di- rectly 1 could leave poor mamnma. Isn't 1t too—" “It'’s awfully good of you to come, dear,” Emily got in. “l've been intending to have you over to take dinner and spend the day. But now that you are back for good—' “Back for good!" sald Dade. *“Mai non, not a bit of it. Mamma says si and w! cawn’t enduah this climate, coula? We're off directly we can decide wheah to go. She wants to go up into the White Mountains, but I've just to go some place wheah they have golf links, don’t you know? The truth js, Em, it's impossibie in this stupid, provincial old hole—I'll be every bit as fat as magpma if I stay heah a minute longah—"" “You miss your exercise?” said Emily, lolling back on the cushions of her divan in an indolence of manner that told how remote exercise was from her wish at that moment. “Don’t speak the word!” cried Dade, pushing out one of her strong hands re Pellantly. I positively cawn't find a thing to do. I tried a cross-country walk yesterday and got chased by a stupid fah- mah and nearly hooked by a cow—to say nothing of this rich Iliinois mud. Mamma owns a few hundred acres of it, Dieu merel, so we don’t have to live hayh on it, though if the—what do you say?—les paysans—Kkeep on crying for a decrease in rent 1 fawncy yol'il see me back hyah actually digging in it The picture of the Emersons’ tenants which Dade drew struck a pang in Em- ily's sociological conscience. She pitied the girl more for her inability to estimate the evils of a system which left her free to wander over the earth seeking that exercise which her clamoring muscles de- manded, while those upon whose labors she lived had to exercise more than their overwrought muscles required thap she did for the remote prospect of her being doomed to labor on the corn lands of Poik County. “I'd go down to Zimmerman's saloon and bowl if it wouldn't shock you all to death. But tell me, how do you feel about bout what—your need of exercise?” “Mon Dieu, no—about the terrible ex- [ose of that interesting protege of yours? On ne pourrait le croire—c’est affreux!"” “Well, no,” Emily said, with a woeful laugh, “if I undemstand your French.” ““What!™ exclaimed the girl. “I thought you were so deeply interested In him. Haven't you worked hard to give him some sort of soclal form, getting him to dawnces and all that sort of thing?” *“No, not to dances, Dade. He doesn't dance.” “Oh, to b‘ suah. eahd"—she? gave heahd that he . lous when you went® to visit Sallle Van Stohn in St. Louis and dawnced with all those men theah. And 1 didn't blame him—those St. Louis men are raeally lovely dawncers, bettah than the Chicago men—they have the measure, but not the grace—though the St. Louis men are nothing at all to the German of- ficers we met at Berlin. Why, my deah, those fellows can waltz across a bal room with a glass of wine on each hand— raeall, She stretched out her well turned arms and held their pink palms up to picture the corseted terpsichorean. “But why didn't you teach him to dawnce?” Emily did not conceal with her_little laugh the blush that came at thls minder of her attempts to overcome Gar- wood’s pride, which had rebelled at the fudignity of displaying his lack of grace in efforts’at the waltz or the easier two- step. **He wouldn't learn.” ““How stupid! But that's nothing now to this othah thing. Had you evah dreamed of such a thing? I thought from what you wrote me that he was the soul of honah. “So he is!"" declared Emily, lifting eyes that blazed a defiance. “But won't it Injure his chawnces of electicn?” “No!"” Emily fairly cried in her deter- mined opposition to the thought, *no, it won’t.”” She sat upright on the divan and leaned toward her friend with a little You don’t mean to tell me you think it true, Dade Dade ceased to rock. She looked at Emily with her black eyes ‘sparkiing through their long lashes and then she squeezed her wrists between her Kknees and sald: I heahd that—and I a ringing laugh— was , downright Harkness, you're in love with Emily's gaze fell. She thrust out her lower lip a little and gave an almost im- perceptible toss to her brown head. She stroked a silken pillow at her side. Dade’s eyes continued to sparkle at her through their long lashes and she feit the convie- tion of their gaze. “Well,” she said at last, gently, going to marry him.” Dade continued to gaze a moment longer and then she swooped over to the divan. She hugged Emily in her strong young arms, almost squeezing the breath from the girl's body. “Bless you, I knew it!" And then she kissed her, but suddenly held her away at arm'’s length as if she werg a child and said with the note of reproach that her claim as_a life-long intimate gave her voice: “But why didn't you tell me?” ou're the first I've toid except papa,” said Emily. “C'est vrai?” said Dade, her jealousy appeased. “Then it's all right, deah—and it's splendid.. ] think. He's a typical American, you know, and the very man you ought to marry. Mamma's been afraid I'd marry one of those foreighnehs and so have I—but it's splendid. And I tell you she settled herseif for con- fidences—“I'll come back from anywheah to the wedding to_be your mald of honah —just_as we used to plan—don't you know? Oh, I'm so glad, and I think it's roble of you; it's just like you. It']l elect him, too, if ydu announce it right away. 1 say, I'll give a luncheon for you and we can announce it then—no, that wouldn't be correct, would {t? We'd have to have the luncheon heah—but it'll elect him. It would in England, where the women go in for politics more than you do, m'est ce past e always spoke of her own land from the detached standpoint a long residence abroad and sometimes a short one gives to expatriates. “And—let's plan it all out now, dyvah. Will you have it at St. Louis, and Doctah Storey >—why—there—there now—" Emily had pillowed her head on Dade’s full bcsom and her long-restrained tears had flooded forth. The larger girl, with the motherly instinct that comes with full brimming health, wrapped her friend in her arms and soothed her, though dis- engaging one hand now and then to wipe the perspiration that bedewed her own brow. e two girls sat there in silence, rocking back and forth among the pil- lows in the darkened parlor, until Dade suddenly broke the spell by sitting bolt uprhifhl and exclaiming: ‘“Mon Dieu, there comes that big De Freese girl. I'm going.” And she rose to effect her inconsistent desertion at once. Turning in from the street a large, tranquil blogde, gowned and gloved and bearing a chiffon parasol to keep the sun from her milky complex- hn.dwal calmly and coolly crossing the yard. ‘She’s got call In her eye!" exclaimed Dade. And then she burried on, before she fled, to say all she had left unsaid: “T'll be ovah this afternoon and we'll plan it all out—and I'm going to make mamma spend next wintah in Washing- ton. It'll help some of her diseases—what's “I'm