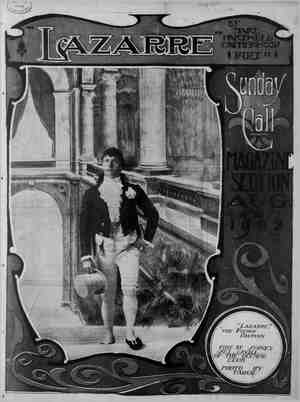

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, August 31, 1902, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SUNDAY CALL. our house!” 1 said. fit in these times. I ought with my King and my the knife. Often 1 am myself for slipping away. houid live to see diSguUStng f00iS of Paris, after the Terror men affecting the k and Komnan manner—greeting one her L & of the nead! They lack coliars, gray i cudgels, and souid have the hair fastened up with ves! The wearer of to be knocked on the head. These creaturs used to congre- gate at the old Feydcau theater, or meet & queue was likely around to talk cla vi The Marquis du Plessy drew himself together with a strong shudder. the desire to stand between him and the shocks of an alien world. Yet there was about him a tenacious masculine strength, an adroitness of self-protection which needed po ¢ fon. “Did the Indian tell you about a man named Bellenger?” 1 inquired. “Belienger is part of the old story about the dauphin’s removal. I heard of him first at Coblenz. And I understand now that he is following you with an- other dauphin, and objecting to you in various delicate ways. Napoleon Bona- r of France, and in the er of Europe, because he has 2 nice sense of the values of men, and the best head for detail that was ever formed in human shape. There is something almost supernatural in BRis grasp of affairs. He lets nothing escape him. The only mis- take he ever made was butchering tne young Duke d’Enghien—the courage and clearness of the man wavered that one in- siant; and by the way, he borrowed my name for the Duke’s incognito during the Journey under arrest! England, Russia, Austria and Sweden are combining egainst Napoleon. He will beat them. For while other men sleep, or amuse themselves, or let circumstances drive them, he is planning success and provid- ing for all possible contingencles. Take & leaf out of the general's book, my boy. No enemy is contemptible. If you want to force the hand of fortune—scheme!— scheme!—all the time!—out-scheme the other feliow!” The Marquis rose from the table. “I am longer winded,” he said, “than a man named De Chaumont, who has been importuning Bonaparte, in season and out of season, to reinstate an American emigre, 8 Madame de Ferrier.” ‘“Will Bonaparte restore her lands?” 1 ssked, feeling my voice like a rope in my throat. “Do you know her family?” . “I knew Madame de Ferrier in Amer- “Their estate lies next to mine. And what is the le De Ferrier like since she is grown ‘A beautiful woman.' “Ab—ah! Bonaparte’s plan will then be eesy of execution. You may see her here this evening in the Faubourg St. Ger- mazin. I believe she is to appear at Mad- &me de Permon's, where Bonaparte may ook in.” My host bolted the doors of his private catinet, and took from the secret part of & wall cupboard the Queen's jewel case. We opened it between us. The first thing I noticed was a gold snuffbox, set with portraits of the King, the Queen &nd their two children. How I knew them I cannot tell. Thelr pictured faces had never been put before my conscious eves until that moment. Other portraits might have been there, I had no doubt, no hesitation. 1 was on my knees before the face I had #een In my spasms of remembrance— with oval cheeks and fair hair roiled high —and open neck—my royal mother! Next I looked at the King, heavier of feature, honest and straight gazing, his chin held upward; at the little sister, a smaller minlg!ure of the Queen; at the ly molded curves o Vil f the child that Before could epeak I ro: n my arme around him. He wheelog. toos k‘Fvléa?f. stood at a little distance and We sald not one wo - traits, but sat down with ‘Tajers EoF, with &gain’ between us. FRR Bt e ,‘These stones and coins ~eler's, monsieur the Marqu?:.’:'” ?‘ile }}Ifd[ed his eyebrows. had ample opportunity, turn them into the exchequer %‘;"tfi: Count of Provence. “Before his quarc rel with the late Czar of Russia he maintained a dozen gentlemen-in-wait. ing, and perhaps as many ladies, to say nothing of priests, servants, attendants of attendants, and guards. This treasure might last him two years. If the King of Spain and his Majesty of Russia got Wind of it and shut off their pensions. it would not last so long. I am too thrifty “e Frenchman to dissipate the hoards of the s;a!z in foreign parts! Yet, if you Question my taste—I will n honesty, Lazarre—" & i I ask ‘I question nothing, monsieur! advice.” lso my “Eh, blen! Then do not be quif punctilious as the gentleman w oug:: turned out of the debtor side of Ste, Pelagle into an alley. “This will not do, says he. S0 around he posts to the emn- trance and asks for admittance again!” “Catch me knocking at Ste. Pelagle for admittance again!” “Then my advice is to pay your tailor, 1t he bas done his work acceptably.” “He has done it marvelously, especiall; in the fitting. v e 7 “‘A Parisian workman finds it no mira- cle to fit 2 man from his old clothes. I took the liberty of sending your orders. Having heard my little story, you under- stand that you owe me nothing but your soclety; and a careful inventory of this trus ‘We were a long time examining the con- ients of the case. There were six bags of coin, all gold louls; many unset gems; rings for the hand; and clusters of var- fous sorts which I knew not how to name, that blazed i a kind of white fire very dazzling. The half-way crown was crusted thick with colored stones the like of which I could not have imagined in 1 dreams. Their names, the Marquis tol me, were sapphires, emeralds, rubles; and large clear diamonds, like beads of rain. When everything was carefully returned to place, he asked: “Shall I still act as your banker?” I begged him to hide the jewel box again end he concealed it in the wall. ‘We go to the Rue Ste. Croix, Lazarre, which i& an impossible place for your friend Bellenger at this time. Do you déance & gavotte?” 1 told him I could dance the Indian corn dance, @nd he advised me to reserve this accomplishment. “Bonaparte’s police are keen on any scent, especially the scent of a prince. His practical mind would reject the Tem- ple story, if he ever heard it; and there are enough live Bourbons for him to watch.” “But there is the Count de Chaumont,” I suggested “He is not a man that would put faith in the Temple story, either, and I under- stand be is kindly disposed toward you.” “I lived in his house nearly a year.” “He is not a bad fellow for the new sort. I feel certain of him. He is coax- ing my friendship because of ancient ami- ty between the houses of Du Plessy and errier.” Dt ia you say, monster, that Bonaparte intends to restore Mme. de Ferrier's lands?” “They have been given to one of his rising officers “Then he will not restore them?” “Oh, yes, with interest! His plan is to give her the officer for a husband.” VIL Even in those days of falling upon ad- wenture and taking hold of life with the errogance of young manhood, I knew the value of money, though it has always been my fault to give it little considera- tion. Experience has taught me that pov- erty goes afoot and sieeps with strange bedfellows. But I never minded going @foot or sharing the straw with cattle. However, my secretary more than once took a hj and with me because he bore the bag; and I did not mind debt chasing my heels like a rising tide. Our Iroquois had their cottages In St. Regis and their hunting cabins on Lake George. They went to church when not drunk and quarrelsome, paid the priest his dues, labored easily, and cared noth. ing for hoarding. But every step of my new life called for coin. As 1 look back on that hour the dom- inating thought rises clearly, To see men admitting that you are what you believe yourself to be, is one of the triumphs of existence. The jewel-case stamped identification upon me. I feit like one who had communicated with the past and received a benediction. There Wwas special provision in the way it came to me; for man loves to believe that God watches over and mothers him, Forgetting—if I had ever heard—how the ents dreaded the powers above when they had been too fortunate, I went with the Marquis in high spirits to the Rue Bte. Croix. There were pots of incense sending little wavers of smoke through the rooms, and the people might have peopled a dream. The men were indeed all smooth and trim; but the women had given rein to their fancies. Our hostess was a fair and gracious woman, of Greek ancestry, as Bonaparte himself was, and her daughter had been married to his favorite general, the Mar- quis told me. I notice only the unusual in ciothing; the scantiness of ladjes’ appare! that clung like the satin and lay upon the oak floor in ridges, among which a man must shove his way, was unusual to me. I saw, in space kept cleared around her chair, one beauty with nothing but san- dals on her feet, though these were white as mlk, silky skinned like a hand, and ringed with jewels around the toes. Benaparte's youngest sister stood re- ceiving court. She was attired like a Bacchante, with bands of fur in her hair, topped by bunches of gold grapes. Her robe and tunic of muslin fine as air, woven in India, had bands of gold, clasped with cameos, under the bosom and on the arms. Each woman seemed to have planned outdoing the others in conceits which marked her own fairness. I lcoked anxiously down the spacious room without seeing Madame de Ferrier. The simplicity, which made for beauty of houses in France, struck me, in the white and gold paneling, and the chimney, which lifted its mass of design to the ceiling. 1 must have been staring at this and thinking of Madame de Ferrier when my name was called in a lilting and ex- cited fashio “Lazarre!” There was Mademoiselle de Chaumont in the midst of gallants, and better pre- pared to dance a gavotte than any other charmer in the room. For her gauze dress, fastened on the shoulders so that it fell not quite off her bosom, reached only to the middle of the calf. This may have been for the protection of rosebuds with which ribbons drawns lengthwise through the skirt, were fringed; but it also showed her child-like feet and ankles, and made her appear tiptoe like a fairy, and more remarkable than any other fig- ure except the barefooted dame. She held a crook massed with ribbons and rosebuds in her hand, rallying the men to her standard by the lively chatter which they like better than wisdom. Madamoiselle Annabel gave me her hand to kiss, and made room for the Marquis du Plessy and me in her circle. I felt abashed by the looks these cour- tiers gave me, but the Marquis put them readily in the background, and delighted 1nlf(he poppet, taking her quite to him- self, “We hear such wonderful stories about’ you, Lazarre! Besides, Doc- tor Chantry came to see us and told us all he knew. Remember, La- zarre belopged to us before you discov- ered him, monsieur the Marquis du Ples- sy! He and I are Americans!” Some women near us commented, as seemed to be the fashion in that soclety, with a frankness which Indlans would have restrained. “‘See that girl! The Emperor may now imagine what his brother Jerome has done! Her father has brought her over from America to marry her, and it will need all his money to accomplish that!" Annabel shook the rain of misty haird at the sides of her rose pink face, and laughed a joyful retort. “No wonder poor Prince Jerome had to g0 to America for a wife! Did you ever see such hairy faced frights as these Pa- risians of the empire. Lazarre fell ill looking at them. He pretends he doesn’t see women, monsieur, and goes about with his coat skirts loaded with books. I used to be almost as much afraid of him as I am of you! ““Ah, mademoiselle, I dread to enter pa- radise.” “Why, monsieur?” “The angels are afrald of mel” ““Not when you smile.” “Teach me that adorable smile of yours!” “Oh, how improving you will be to La- zarre, monsieur! e never pald me a compltment in his He never sald anything but the trut! “The lucky dog! What pretty things he had to say!” Annabel laughed and shook her mist in great enjoyment. I liked to watch her, yet I wondered where Madame de Ferrler ‘was, and could not bring myself to in- quire. ““These horrible incense pots choke me,” Annabs abel. “I like them,” said the Marquis, “Do you? So do L,” she instantly agreed with him. “Though we get enough incense in church.” “I should think so! Do you like mass?’ “I was brought up on my knees. But I never acquired the real devotee’s back.” “Sit on your heels,” imparted Annabel in strict confidence. “Try it.” *“I will. Ah, mademoiselle, any one who could bring such comfort into religion might make even wedlock endurable!” dame de Ferrier appeared between the curtains of a deep window. She was talk- ing with Count de Chaumont and an offi- cer in uniform. Her face pulsed a rosi- ness like that quiver in winter skies which we call northern lights. The clothes she 'wore, being always subdued by her head and shoulders, were not noticeable like other women's clothes. But I knew as soon as her eyes rested on me that she found me changed. De Chaumont came a step to meet me, and I felt miraculously equal to him, with some power which was not in me be- fore. “You scoyndrel, you have fallen inlo luck!” he said heartily. “One of our proverbs is, ‘A bl find an acorn once in a whil ““There isn’t a better acorn in the woods or one haruer to shake down. How did you do it?” I gave him a wise smile and held my tongue; knowing well that if I had re- mained in Ste. Pelagie and the fact ever came to De Chaumont's ears, like other human beings he would have reprehended my plunging into the world. “We are getting on tremendously, La- zarre! When your inheritance falls in, come back with me to Castorland. We will found a wilderness empire!” I did not inquire what he meant by my inheritance falling in. The Marquis pressed behind me, and when I had spoken to Madame de Ferrier I knew it was his right to take the hand of the woman who had been his little neighbor. “You don’t remember me, madame?” *Oh, yes, I do, Monsieur du Plessy; and your wall fruit, too!” “The rogue! Permit me to tell you those pears are hastening to be ready for Yyou once mor “And Bichet! Bichette alive “She is alive, and draws the chair as well as ever. I hear you have a little son. He may love the old pony and chair as you used to love them.” “Seeing you, monsieur, is like coming again to my home!"” “I trust you may come soon.” They spoke of fruit and cattle. Neither dared mention the name of any human companion associated with the past. I took opportunity to ask Count de Chaumont if her lands were recovered. A baffled look troubled his face. it “The Emperor will see her to-night,” he answered. “It is impossible to say what can be done until the Emperor sees her.” “Is there any truth in the story that he will marry her to the officer who holds her estate?” The Count ’S;o:mTA. fble." “No—no! at’s impossible.’ “Will the officer gell his rights if Mld: eme de Ferrier's are not acknowledged?” “I have th&ught!c that. And I want to consult the Marquis. ‘When he had a chance to draw the Mar- quis aside, I could speak to Madame de Ferrier without being overheard; though my time might be short. She stood be- tween the curtains, and the man in uni- form had left his place to me. nd pig will , monsieur—is dear old nd I am glad,’ 1 “I am here because I love you. . She held a fold of the curtain in her hand and looked down at it; then up at m “You must not say that again.” “Why?” “You know why."” “I do not.” “Remember who you are.” 1 am your lover.” She looked quickly around the buzzing drawing-room and leaned cautiously nearer. “You are my sovereign.” “I believe that, Eagle. But it does not foliow that I shall ever reign.” “Are you safe here? Napoleon Bona- parte has gpies.” “But he has for old aristocrats like the Marquis du Plessy.” ““Yet remember what he did to the Duke d’Enghien. A Bourbon Prince is not al- lowed in France.” “How mauy Iyeo le consider me a Bour- bon Prince? T told l_zmx why I am here. Fortune has wonderfully heiped me since I came to France, Laxarre, the dauphin from the Indian Ec‘amnvl“ brazenly asks you to_marry him, le ! WHer face ‘blanthed white, but she ughed. "fio ~se Ferrier ever took a base advan- tage of royal favor. Don’t you think this is a strange conversation in a drawing- room of tne empire? I hated myself for being here—until you came in. “Eagle, have you forgotten our supper on the island?” “Yes, sire.”” She scarcely breathed the word. “My unanointed title is Lazarre. And I suppose you have forgotten the fog and lherounmm. too?’ Yyes Her lifted chin expressed a strength I could not combat. The slight, dark-haired irl, younger than myself, mastered and rew ‘me as if my spirit was a stream, and she the ocean into which it must flow. Darkness like that of Ste. Pelagie dropped over the brilliant room. T was nolfiing after all but a palpitating_boy, veniuring because he must venture. Light seemed to strike through her blood, how- ever, endowing her with a splendid pallor. “I'am going,” I determined that mo- ment, “to Mittau.” The adorable curve of her eyellds, un- like any other eyelids I ever saw, was lost to me, for her eyes flew wide open. o She looked around and hesitated to pro- nounce the name of the Count of Pro- vence. b ‘l‘Yel. I am elongs to me. 4 “Yo{\ have the Mar%ul! for a friend. “And I have also Skenedonk and our tribe for my friends. But there is no one- who understand that a man must have some love.” ‘“‘Consult Mart}uis du Piessy about go- ing to Mittau. It may not be wise. d war is threatened on the frontier. “I will consult him, of course. But I am going to find some one who oing. Kzal"l".. there were ladies on the ship who cursed and swore, and men who were drunk the greater part of the voyage. I was brought up in the old-fashioned way by the BSaint Michels, 8o I know nothing of present customs. But it seems to me our times are rude and wicked. And you, just awake to the world,” have yet the innocence of that little boy who sank into the strange and long stupor. It you changed I think I could not bear t “T will not change.” . A stir which must have been widening through the house as a ripple widens on a lake, struck us, and turned our faces with all others to a man who stood in front of the chimney. He was not large in person, but as an individual his pres- ence was massive—was penetrating. I could have topped him by head and shoul- ders; yet without mastery. He took snuff as he slightly bowed in every direction, shut the lid with a snap and fidgeted as if impatient to be gone. He had a mouth of wonderful beauty and expression, and his eyes were more alive than the eyes of any other man in the assembly. 3 his gigantic force as his head dipped fo ward and he glanced about under his brows. ““There {s the Emperor,” De Chaumont told Eagle; and I thought he made in: decent haste to return and hale her away before Napoleon. The greatest soldier in Europe passed from one person to another with the air of doing his duty and getting rid of it. Presently he raised his voice, speaking to Mme. de Ferrier so that all in the room might hear. ““Madame, I am pleased to see that you wear leno. I do not like those English muslins, sold at the price of their weight in gold, and which do not look half as well as beautiful white leno. Wear leno, cambric or silk, ladies. and then my man- ufacturers will flourish.” I wondered if he would remember the face of the man pushed against his wheel and called an assassin when the Marquis du Plessy named me to him as the citizen Lazarre. “You are a Jucky man, Citizen Lazarre, to gain the Marquis for your friend. 1 have been trying a number of years to make him mine.” “All Frenchmen are the friends of Na- poleon,” the Marquis said to me. I spoke directly to the sovereign, there- by violating etiquette, my friend told me afterward, laughing; and Bonaparte was a stickler for precedent. “But all Frenchmen,” I could not help reminding the man in power, ‘“are not faithful friends.” He gave me a sharp look as he passed on and repeated what I afterward learned wae one of his favorite maxims: “A falthful friend is the true image.” VIIL “Must you go to Mittau?’ the Marquis du Plessy said when I tofd him what 1 intended to do. “It is a long, expensive post journey; and part of the way yom may not be able to st. Riga, on the gulf beyond Mittau, is a fine old town of pointed f‘nble! and high stone houses. But when I was in Mittau I found it a mere winter camp of Russian nobles. The houses are low, one-story structures. There is but one castle, and in that his Royal Highness the Count of Provence holds mimic court.” We were riding to Versallles, and our horses almost touched sides as my friend put his hand on my shoulder. “Don’t go, Lazarre. You will not be welcome there.” “I must go, whether I am welcome or not.” “But I may not last until you come back.” “You will last two months. Can't I post to Mittau and back in two months?" “God knows.” I looked at him drooping forward in the saddle, and said: “If you need me I will stay, and think no more about seeing those of my own blood.” “I do need you; but you shall not stay. You shall go to Mittau in my own pos carriage. It will bring you back sooner. But his post-carriage I could not accept. The venture to Mittau, its wear and tear and waste, were my own; and I promised to return with all speed. I could have un- dertaken the road afoot, driven by the necessity I felt. ““The Duchess of Angouleme is a good rl,”” sald the Marquis, following the ine of my thoughts. “She has devoted herself to her uncle and her husband. ‘When the late Czar withdrew his pen- slon, and turned the whole mimic court out of Mittau, she went to her uncle, and even waded the snow with him when they fell into straits. Diamonds given to her. by her grandmother, the Empress Mar'a Theresa, she sold for his support. But the new Czar reinstated tnem; and though they live less pretentiously at Mittau in these days, they still have their priest and almoner, the Duke ' of Guiche, and other courtiers hanging upon them. My boy, can you make a court bow and walk backwards? You must practice before going to Russia. B “Wouldn't it be better,” I said, ‘for those who know how, to practice the ac- complishment before me?" “Imagine the Count of Provence step- ping down and playlns royalty to do that!” my friend laughed. “I don't know why he shouldn’t, since he knows I am alive. He has sent money every year for my support.’” “‘An ‘established custom, Lazarre, gains strength every day it is continued. You see how hard it is to overturn an exist- ing system, because men have to undo the work they have been doing perhaps for a thousand years. Time gives enor- mous stability. ~Monsieur the Count of Provence has been practicing _royalty since werd went out that his nephew had died in the Temple. It will be no easy matter to convince him you are fit to play King in his stead.” This did not 'disturb me, however. I thought more of my sister. And I thought of vast stretches across the center of Eu- rope. The Indian stirred in me, as it al- ways did stir, when the woman 1 wanted was withdrawn from me. could not tell my friend, or any man, about Madame de Ferrier. This story of my life is not to be printed until I am gone from the world. Otherwise the things set down so freely would remain buried in myself. Some beggars started from hovels, run- ning like dogs, holding _diseased and crooked-eyed children up for alms, and Eleldlns for God's sake that we would ave pity on them. When they disap- peared with their coin I asked the.Mar- quis if there had always been wretched- ness in France. “‘There is always wretchedness every- where,” he answered. ““Napoleon can turn the world upside down, but he can- not cure the disease of heredi pover- ty. I never rode to Versailles without en- countering these people.” ‘When we entered the Place d'Armes fronting the palace, desolation worse than that of the beggars faced us. That vast nohlwfle. untenanted and sacked, sym- bolized the varnished monarchy of France. Doors stood wide. The court was strewn with litter and fllth; and grass started rank betwixt the stones where the proud- est courtiers in the world had trod, I tried to enter the Queen’s rooms, but sat on the steps leading to them, hofdinl my tead in my hunds. It was as impossible as it had.been to enter the Temple. The fountains which once made a con- cert of mist around thir lake basin, sat- isfying like music, the Marquis sald, .were dried, and the figures kroken. Millions Pad been spent upon this domain of kings and nothing but the summer’s natural Yyerdure was left to unmown stretches. The foot shrank from sending echoes through empty palace apartments, and from treading the weedy margins of canal and lake. % “I should not have brought vou here, Lazarre,” saild my friend. “I had to come, monsieur.” ‘We walked through meadow and park to the little palaces called Grand and Petit Trianon, where the intimate life of the last royal family had been lived. I looked well at their outer guise, but could not explore them. The groom held our horses in the street that leads up to the Place G'Armes, and as we sauntered back, I kicked old Jeaves which had fallen autumn after autumn and banked the pa 1t rushed over me again! I feit my arms go above my head as they did when I sank into the depths of recollection. ‘“‘Lazarre! Are you in a fit?” The Mar- quis du Plessy seized me. “I remember! I remember! I was kick- ing the leaves—I was walking with my father and mother—somewhere—some- where—and something threatened us!” 5 “It was in the garden of the Tuileries,” sald the Marquis du Plessy sternly. “The meb threatened you, and you were going before the National Assembly! I walked ?éhlnd. I was there to help defend the ng. We stood still until the paroxysmal rending in my head ceased. Then I sat on the grassy roadside trying to smile at the Marquis, and shrugging an woloiy for my weakness. The beauty of the arched trees disappeared, and when next I recognized the world we were moving slowly toward Paris in a heavy carriage, and 1 was smitten with the conviction that my friend had not eaten the dinner he ordered in the town of Versailles. I felt ashamed of the weakness, which came like an eclipse and withdrew, leav- ing me in my strength. It ceased to visit me within that year and has never trou- bled me at all in later days. Yet, incon- sistently, I look back as to the glamour of youth; and though it worked me hurt and shame, I half regret that it is gone. The more I saw of the Marquis du Ples- Sy the more my slow, tenacious heart took hold on him. We went about every- where together. I think it was his_hope to wed me to his company and to Paris, and shove the Mittau venture into an in- definite future; yet he spared no pains in i:hlalnlng for me my passports to Cour- and. 3 n At this time, with cautious, half-reluct- ant hand, he raised the veil from a phase of life which astonished and revolted me. I loved a woman. The painted semblances of women who inhabited a world of sen- sation had no effect upon me. “You are wonderfully fresh, Lazarre,” the Marquls said. “If you were not so big and male 1 would call you made- moiselle! Did they never sin in the Amer- ican backwoods?’ 3 Then he took me in his arms lke a mother and kisséd me, saying, ‘“‘Dear son and sire, T am worse than your great- srandfather!” Yet my zest for the gayety of the old city grew as much as he desiréd. The golden dome of the Invalides became my Eixbble of Paris, floating under a sunny y. Whenever I went to the hotel which De Chaumont had hired near the Tulleries’ Madame de Ferrier received me kindly, having always with _her Mademoiselle de Chaumont or Miss Chantry, so that we never had a word in private. I thought she might have shown a little feeling in her rebuff, and pondered on her point of view re- garding my secret rank. De Chaumont, on the other hand, was beneath her In everything but wealth. How might she regard stooping to him? Miss Chantry was divided between en- forced deference and a Saxon_necessity to tell me I would not last. I saw she considered me one of the upstarts of the empire, singularly favored above her brother, but under my finery the same g‘arench savage she had known in Ameri- Eagle brought Paul to me, and he tod- dled across the floor, looked at me wise- ly, and then climbed my knee. Doctor Chantry had been living in Parls a life above his dreams of luxury, When occasionally I met my secretary he was about to drive out; or he was returning from De Chaumont’s. And there I caught Iy poor master reciting poems to Anna- bel, who laughed and yawned, and made faces behind her fan. I am afraid he drew on the Marquis' oldest wines, find- ing indulgence in the house; and he sent extravagant bills to me for gloves and lawn eravats. It was fortunate that De Chaumont took him during my absence. He moved his belongings. with positive rapture. The Marquis and I both thought it prudent not to publish my journey. octor Chantry went simpering, and abasing himself before the French mnoble Wwith the complete subservience of a Blaxc‘n when a Saxon does become subser- vient. “The fool is laughable,” said the Mar- quis du Plessy. ‘‘Get rid of him, Lazarre. He s fit for nothing but- hanging upon some one who will feed him.”” “He {s my master,” I answered. a fool myself.” “You will come back from Mittau con- vinced of that, m}r boy. The wise course is to join yourself to events, and let them draw your chariot. My dislikers say I have temporized with fate. It s true I am not so righteous as to smell to heaven. But two or three facts have been deeply impressed on me. There is nothing more aggressive than the vir- tue of an ugly, untempted woman; or the determination of a_young man to set every wrong thing in the world right. He cannot walit, and take mellow Interest in what goes on around him, but must leap into the ring. You could live here Wwith me indefinitely, while the nation has Bonaparte like the ‘measles. When the disease has run its course—we may be able to bring evidence which will make it necessary for the Count of Provence 'Igh:“"’ten here that France may have a “I am L want to see my sister, monsieur.” ‘And lose her and your own cause for- ever.?” But he helped me to hire a strong traveling chaise, and stock it with such comforts as it would bear. He also turned my property over to me, recom- mending that I should not take it into Russia.” Half the jewels, at least, I con- sidered the property of the Princess in Mittau; but his precaution influenced me to Ieave' three bags of coin in Doctor Chantry’s care; for Doctor Chantry was the soul of thrift with his own; and to send Skenedonk with the jewel case to the Marquis’ bank. The cautious Oneida took counsel of himself and hid it in the chaise. He told me when we were three days out. It is as true that you are driven to do some things as that you can never en- tirely freo yourself from any life you bave lived. " That sunny existence in the Faubourg St. Germain, the morning and evening talks with a man who bound me to him as no other man has since bound me to him, were too dear to leave even briefly without wrenching - pain. I dreamed nightly of robbers and disaster, of being ignominiously thrust out of Mit~ tau, of seeing a woman whose face was & blur and who moved backward from me when I called her my sister; of troops marching across'and trampling me in the earth as straw. I groaned in spirit. Yet to Mittau I was spurred by the kind of force that seems to press from unseen distances, and is as fatal as tempera- ment. ‘When I pald my last visit at De Chau- mont’s hotel, and sald I was going into the country, Eagle looked concerned, as @ De Ferrier should; but she did not turn her head to follow my departure. The gnma of man and woman was in its most lindfold state between us. There was one, however, who watched me out of sight. The Marquis was more agitated than I liked to see him. He took snuft with a constant click of the Iid. The hills of Champagne, green with vines, and white as with an underlay of chalk, rose behind us. We crossed the frontier, and German hills took _their places, with a castle top?ln‘ each. I was at the time of life when interest stretches eagerly toward every object; and though this - journey cannot be set down in a story as mine, the novelty—even lon the risks, mfichucu and wearinesses of continual post travel, come back like an invigorating breath of salt water. The usual route carrled us eastward to Cracow, the old capital of Poland, scatterad in ruined grandeur within its brick walls, Beyond it I remember a stronghold of the middle ages called the fortress of Landskron, The peasants of this cnuntr{ men in shirts and drawers of coarse linen, and women with braided hair hanging down under linen vells, stopped their carts as 800n as a post-carriage rushed Into sizht, and bent almost to earth. At post-houses the servants abased themselves to take me by the h In no other country was the spirit of man so broken. Poles of high birth are called the Frenchmen of the north, and we saw fair men and wo- men in sumptuous molonaises and long ol ‘who appeared luxurious in their traveling carriages. ~But stillness and Ssolitude brooded on the land. From Cra- cow to Warsaw wide reaches of forest darkened the level. Any open circle was beited around the horizon with woods, pines, firs, beech, and small oaks. Few cattle fed on the pastures, and stunted crops of gra. fint. grain ripened in the melancholy From Cracow to Warsaw is a distance of one hundred and thirty leagues, if ths postilion lied not, yet on that road we met but two carriages and not more than ?agggze:acfia;mfi Scatatierlng wooden vil- 3 ne of 2 long intervals. Tt Pc;n-houses were kept by Jews, who fed fis dn the rooms where = their = families f\;e X Mllk and eggs they had none to S":;‘uos‘; tshned thelrdbedb were piles of round, unéenanted b}$ i seldom clean, never ©Sgars ran beside us on the wretched roads as neglected as themselves. W%ere our horses did not labor through sand, the marshy ground was paved with sticks and boughs, or the surface was bullt up With trunks of trees laid_crosswise. In spacious, ill-paved ‘Warsaw, through which the great Vistula flows, we rested two days. I knelt with confused thoughts trying to pray In the Gothic cathedral, :‘{:hwl:‘l)l‘(lcd p&!tdlt into the old town, of ses and narrow stre 3 part of Paris. Tl In Lithuania the roads were paths wind- ing through forests full of stumps and roots. The carriage hardly squeezed along, and eight little horses attached to it in the Polish way had much ado to draw us. The postilions were young boys in coarse linen, hardy as cattle, who rode bareback league upon league. Old bridges cracked and sagged when we crossed them. And here the forests rose scorched and black in spots, because the peasants, bound to pay their lords turpentine, fired pines and caught the heated ooze. ‘Within the proper boundary of Russia our way was no better. There we saw queer projections of boards around trees to keep bears from climbing after the hunters. The Lithuanian peasants had few wants. Their cars were put together ‘without nails. Their bridles and traces were made of bark. They had no toos but hatchets. A sheepskin coat and round felt cap kept a man warm in cold weather. His shoes were made of bark, nndf his home of logs with pent-house roof. In houses where travelers slept the can- dles were laths of deal, about five feet long, stuck into crevices of the wall or hung over tables. Our hosts carried them about, dropping unheeded sparks upon the straw beds. In Grodno, a town of falling houses and ruined palaces, we tl_;lesl.ed again before turning directly north. There my heart began to sink. We had spent four weeks on a comfortless road, working always toward the goal. It was nearly won. A speech of mv friend the Marquis struck itseif out sharply in the " northern light. o re_not the only pretender, my dea¥°go; Don’t go to Mittau expecting to be heralded as a novelty. At least two casants have started up clainfing to be ?he prince who did not die in the Temple, and have been cast down again, com- laining of the treatment of their dear flster! g'J"he Count d'Artois says he would rather saw wood for a 1lvln§ than be king after the English fashion. would rather be the worthiess old fellow I am than be king after the Mittau fashion; especially when his Majesty, Louis XVIII, sees you coming!"” IX. Purposely we entered Mittau about sun- set, ;ph!ch ‘was nearer 10 o'clock than 9 in that northern land; coming through wheat lands to where a network of streams forms the river Aa. In this broad lap of ihe province of Courland sat Mittau. Yel- gava it was called by the people among whom we last posted, and they pro- nounced the word as if naming sométhing as great as Paris. s It was already July, St. John's day be- ing two weeks gone; yet the echoes of its markets and feastings lingered. The word “Johanni” smote even an ear deaf to the language. It was like a dissolving fair. “You are too late for Johanni,” sald the German who kept the house for trav- elers, speaking the kind of French we heard in Poland, ‘“Perhaps it is just as well for you. This Johanni has nearly ruined me!"” Yet he showed a disposition to hire my singular servant from me at a wage, walking around and around Skenedonk, who bore the scrutiny like a pine tree. The Onema enjoyed his travels. It was easy for him to conform to the thoughts and habits of Europe. We had not talked about the venture into Russia. He sim- ply followed me where I went without asking any questions, proving himself a faithful friend and liberal minded gentle- man. ‘We supped privately, and T dressed with care. Horses were put in for our last short post of a few streets. We had suf- fered such wretched quarters on the way that the German guest-house spread itself commodiously. Yet its walls were the flimsfest slabs. I heard some animal stretching and whining in the next cham- ber. On the post-road, however, we had not always a wall betwixt ourselves and the dogs. The palace in Mittau stood conspicuous upon an island in the river. As we ap- proached, it looked not unlike a copy of Versailles. The pile was by no means brilliant with lights, as the court of a king might glitter, finding reflection upon the stream. We drove with a clatter upon the paving, and a sentinel challenged us. I had thought of how I should obtain access to this scheduled royal family, and Skenedonk was ready with the queen’s Jjewel-case in his hands. Not on any ac- count was he to let it go out of them until I took it and applied the key; but gaining audience with Madame d’Angouleme, he was to tell her that the bearer of that casket had traveled far to see her, and waited outside. Under guard the Oneida had the great doors shut behind him. The wisdom of my plan looked less conspicuous as time went by. The palace loomed silent, with- out any cheer of courtiers. The horses shook their straps, and the postilion hung lazily by one leg, his figure distinct against the low horizon still lighted by after-glow. Some Mittau noises came across the Aa, the rumble of wheels, and a barking of dogs. ‘When apprehension began to pinch my heart of losing my servant and my whole fortune in the abode of honest royal peo- ple, and I felt myself but a poor outcast come to seek a princess for my sister, a guard stood by the carriage, touching his cap, and asked me to follow him. ‘We ascended the broad steps. He gave the password to a sentinel there, and held ‘wide one leaf of the door. He took a can- dle; and otherwise dark corridors and ante-chambers, somber with heavy Rus- sian furnishings, rugs hung against the walls, barbaric brazen vessels and curious vases, passed like a half-seen vision. Then the guard delivered me to a gen- tleman in a blue coat, with a red collar, who belopged to the period of the Marquis du Plessy without being adorned by his whiteness and lace. The gentleman star- ing at me, strangely polite and full of sus- picion, conducted me into a well-lighted 1oom where Skenedonk waited by the far- ther door, holding the jewel-case as tena- ciously he would a scalp. I entered the farther door. It closed be- hind me. A girl stood in the center of this inner room, looking at me. I remember none of its fittings, except that there was abund- ant light, showing her clear blue eyes and fair hair, the transparency of her skin, and her high expression. She was all in black, except a floating muslin cape or fichu, making a beholder despise the fin- ery of the empire. ‘We must have examined each other sternly, though I felt a sudden giving way and heaving in my breast. She was so high, so sincere! If I had been unfit to meet the eyes of that Princess I must have shriveied before her. side her figure swayed, and another young girl, the only attend- ant in the room, stretched out both arms to_catch her. We put her on a couch, and she sat £ping, uupgonefl by the lady In walt- ng. Then the tears ran down her face, and I kissed the transparent hands, my own flesh and blood, I believed that hour as I believe to thi: 0 Louis—Louis! The wonder of her knowledge and ac- ceptance of me, without a clalm bein; put forward, was around me like a clou “You were s0 like my father stood there—I could see him a parted from us! What mirac) stored you? How dld you find here? You are surely Louls?* 1 sat down beside her, keeping one hand b“fiefin mlnle.b 5 “Madame, I believe as you believe, that I am Louis Charles, t;e dauphin of And I have come to you first, as my own Hesh and blood, who must have more knowledge and recollection of things past than I myself can have. I have not long been waked out of the tranced life I formerly lived.” have wept more tears for the little roken in intellect and exiled e thin wethan for my father and puother. . ‘Fney weré at. peace. but yoil, poor child, wiat hope was there for you! Was the person wiio had you in charge kind ‘to you? He must have been, You have grown to be such a man as 1 wou.d Lave you!" Everybody has been kind to me, my sister.” &2 hey look in that face and be unl%i:‘::‘g Y the"thousana questions have to ask must be deterred unul the hing sees you. 1 cannot wait® him to see you! Mademoiseile de t.nug,s,y. send a message at once to the Kingl B The lady in waiting_witharew to the door, and the x-ayalx Duchess quivered with eager anticipation. e tave Bad pretendea dauphins, to add tnsuit to exile. You may not take the hung unaware as you took me! He wi have proofs as plain as his Latin verse. But you will find nis Majesty ail that a father cou.d be to us, Louis! I think there never was a man, so unselfish!— except, indeed, my husband, wnom you cannot see until he recurns.’ Again 1 kissed my sister’s hand, =Wo gazed at eacn other, our different breed— ing stil mdKing strangeness between us, acress which [ yearned, and she examined me. Many a time since I have reproached myself for not improving those moments with the most canad and mnight- minded Princess in liurope, by fore- stalling my enemies. 1 should have told her oi my weakness insiead of sunuing my strengih in the love of her. I saowid have mace her see my actual posidon and the natura: antagonism of the King, Who would not so readily see a suong personal resemblance when that was not emphasized by some mental stress, as sne and three very diifcrent men had seen it. Instead of making cause witn Ler, how- ever, I said over and over—‘Marie ‘Therese! Marije Therese!”—like a home- sick boy come again to some familiar pres- ence. “You are the only cne of my fam- ily I have seen since wakng, except Louis Phiiippe.” “Don't speak of that man, Louis! I de-~ test the house of Orieans as a_Caristian should detest only sin! His father doom- ed ours to death!” “But he is not to blame for what his father did.” »‘What do you mean by waking?" :‘Coming t0 my senses.” “‘All that we sha.l hear about when the King sees you.” I knew your picture on the snuffbox.” ‘*What snuffbox 7" iThe one in the Queen’s jewel-case.” ““Where did you find that jewel-case?” “Do you remember the Marquis du Plessy?” “Yes. A lukewarm loyalist, if loyalist at all in these times.” “My best friend.” “I will say for him that he was not among the “first emigres. If the first emigres had stayed at home and helped their King, they might have prevented the Terror.” “The Marquis du Plessy stayed after the Tuilleries was sacked. He found the Queen’s jewei-case and saved it from con- fiscation to_ the state.” “Where did he find it? Did you recog- nize the faces?” “Oh, instantly.” The door opened, deferring any story, for that noble usher who had brought me to the presence of Marie Therese stood there, ready to conduct us to the King. My sister rose and I led her by the hand, she going confidently to return the dauphin to his family, and the dauphin going like a fool.” ‘Seeing Skenedonk standing by the door, I must stop and nt the key to the lock of the Queen's casket and throw the lid back to show her proofs given me by one who belleved in me in spite of myself. The snuffbox and two bags of coin were gone, 1 saw with con- sternation, but the Princess recognized 80 many things that she missed nothing, controlled herself as her touch move from trinket to trinket that her mother had worn. ““Bring that before the King.” she sald. And we took It with us, the noble in blue coat and red collar cartying it. His Majesty,” Marie Therese told me as we passed along the corridor, “tries to preserve the etiquette of a court in our exile. But we are paupers, Louls. And, mocking poverty, Bona- parte makes overtures to him to sell tae right of the Bourbons to the throne of France!"” She had not yet adjusted her mind to the fact that Louis XVIII was no longer the one to be treated with by Bonaparte or any other potentate, and the pretend- er leading her smiled like the boy of twenty that he was. “Napoleon can have no peace while a Bourbon in the line of succession lives.” Oh, remember the Duke d'Enghien she whispered. Then the door of a lofty but narrow cabinet, lighted with many candles, was opened, and I saw at the Tarther end a portly gentleman seated in an arm- chair. A few gentlemen and two ladies in waiting, besides Mademoiselle de Choisy, attended, Louis XVIII rose from his seat as my sister made a deep obeisance to him, ana took her hand and kissed it. At once, moved by some singular maternal im- pulse, perhaps, for she was half a dozen years my senior, as a mother would Whimsically decorate her child, Marie Therese took the half circlet of gems from the casket, reached up, and set it on my head. For an instant T was crowned in Mit- tau, with my mother’s tiara. I saw_the King’s features turn to gran- ite, and a dark red stain show on his Jjaws like the coloring on stone. The most benevolent of men, and by all his traits he was one of the most benevolent, have their pitiless moments. He must have been Frepared to combat a pretender be- fore I entered the room. But outraged majesty would now take its full venge- ance on me for the unconsidered act of the child he loved. “First two peasants, Hervagault and Bruneau, neither of whom had the au- dacity to steal into the confidence of the tenderest princess in Burope with the to. kens she must recognize, or to penetrate into the presence,” spoke the King mow an escaped convict from Ste. Pela- gie, a dandy from the empire!” I was only twenty, and he stung me. “Your royal Highness,” I said, speak- ing as I believed within my rights, “my sister tries to put a good front on my intrusion into Mittau.” I took the coronet from my head and gave it again to the hand which haa crowned me. Marie Therese let it fail, and it rocked near the feet of the King. “Your sister, monsiear! What right have you to call Mme. d’Angouleme your sister?” ““The same right, monsieur, have to cjll her your niece.” The features of the Princess became pinched and sharpened under the soft- ness of her fair hair. h-'?sn—e, if this is not my brother, who is a7 Louis XVIII may have been tender to her every other moment of his life, but he was hard then, and looked beyond her mward the door, making a sign with his a; hand. That strange sympathy which works in me for my opponent, put his outraged dignity before me rather than my own wrong. ~Deeper, more sickening than death, the first faintness of self-distrust came over me. What if my half-memories were unfounded hallucinations? What 1t my friend Louis Philippe had made a tool of me to annoy this older Bourbon branch that detested him? What if Bellenger's recognition and the Marquls du Plessy’'s and Marie Therese’s went for nothing? What if some other and not this angry man had sent the money to America—. The door ofenod again. We turned our heads and grew hot at the cruelty which put that idiot befors my sister's eyes. He ran on all fours, his gaunt Wwrists exposed, until Bellenger, advanc- ing behind, took him by the arm and made him stand erect. It was this poor creature I had heard scratching on the other side of the inn wall. How long Bellenger had been before- hand with me in Mittau 1 could not guess. But when I saw the scoundrel who had laid me in Ste. Pelagle and doubtless dropped me in the Seine, ready to do me more mischief, smu‘f and smooth shaven and fine In the red-colldred blue coat Which seemed to be the prescribed uni- form of that court, all my confidence re- turned. I was Louis of ce. I could laugh at anything he had to say. vaBnecmém hl'x;x entered ‘d priest, who ad- ed up the room and made’ obe!san to the King, as Bellenger aid. 5 Mme. d'Angouleme looked once at the idiot and hid her eyes; the King protect- ing her. I said to myself: It will soon be against m: yours, that she hides her t’ ce{rle:nthunel of Pr.a:lence!" e e was as e man said to witness: o b “We shall now hear the truth.” The few courtiers, enduring with hardi- ness a sight which they perhaps had seen before though Mme. d' uleme had not, made a rustle among themselves as if echoing: »Yes, now we shall hear the truth!" The King again kissed my and placed her in a seat beside his chair, which he resumed. yworth,” ‘‘Monsieur he “having stood on tfi‘:“mfld with that you breast, not ace, my ex- the Abbe said. e At i S s AR AR M e AR o i S N RN . 9 o e s o R LA S S I rtyred sovereigm, as priest and s, 4 eminently the one to con- duct an examination like this, which touches matters of conscience. We leave it in his hands.” h, filne and sweet of Abbs . Ragewany facing el- sence, siood by the King, l»errfger and the idiot. That poor creature, astonished by his environment, gazed at the high room corners, or smiled experi- mentaily at the courtiers, stretching his cracked lips over darkened fangs. “You are admitted here, ; said the priest, “to answer his Majesty questions in the presence of witnesses. “I thank his Majesty,” said Beilenger, The abbe began as if the idiot at- tracted his notice for the first time. “Who is the unfortunate child you ith your right ha o ne huphin of Erance, monsieur the abbe,” spoke out Bellenger, his left hand n_his hip. 3 “Vvh.u!p Take care what you say! How do you know that the dauphin of France is_yet among the living?" Bellenger's countenance changed, and he took his band off his hip and let it own. B oeivea e prince, monsieur, from those who took him out of the Temple Prison.” e “And you never exchanged him for an- other person, or g‘nowed him to be separated from you?" Bellenger swore with < ghastly lps— “Never, on_my hopes of salvation, mon- sieur the abbe!" “Admitting that somebody gave you this child to keep—by the way, how oid is he?” o “About twenty years, monsieur. “What right had you to assume he w: the dauphin?” “I had received a yenrli pension, mo: sieur, from his Majesty himself, for the maintenance of the prince.” “You received the yearly _pension through my hand, acting as his Majesty's almoner: His Majesty was ever too bountiful to the unfortunate. He has many dependents. Where have you lived with your charge?” “We lived In America, Sometimes. in the woods, and sometimes in towns. ““Has he ever shown hopeful signs of recovering his reason?” “Never, monsieur the abbe.” Having touched thus lightly on the case of the idiot, Abbe Edgeworth turned to me. The King's face retained its rlflfl. hardness. gBut Bellenger's pass from shade to shade of baffled confidenc: covering only when the priest said: “Now look at lh{,ntyo\l_'l}t man. Have you ever seen him before?” 3 “Yes, monsieur, I have; both in the American woods, and in Paris. “What was he doing In the American ‘woods?"* “Living on the bounty of one Cou t de Chaumont, a friend of Bonaparte's. “Who is he?” “A French half-breed, brought up among the Indians. ‘““What name do “He is_ called Lazarre.” “But why is a French half-breed named Lazarre attempting to force blmgelt on the exiled court here in Mittau? “People have told him that he re- sembles the Bourbons, monsieur. *“Was he encouraged in this idea by the lfleng of Bonaparte whom you men- tioned > “I think not, monsieur the abbe. But I heard a Frenchman tell him he was like the martyred King, and since that hour he has presumed to consider himself the dauphin.” “Who was this Frenchman?" “The Duke of Orleans, Louis Philippe de Bourbon, monsicur the abbe. There was an expressive movement among the courtiers. “Was Louis Philippe instrumental in sending him to France?’ “He was. He procured shipping for the tetender.” % pretender reached FParis *““When the what did he do “He attempted robbery, and was taken in the act and thrown into Ste. Pelagie. 1 saw him arrested.” ‘“What were you doing in Paris?” “I was following an watching thi dangerous pretender, monsieur the abbe. *“Did you leave America when “The evening before, monsieur. And we outsailed him." 3 *Did you leave Paris ‘when he did?” “Three days later, monsieur. But we passed him while he rested.” “Why do you call such an insignificant person a dangerous frelmd‘r? “‘He is not insignificant, monsieur; as ou will say when you hear what he did n Paris.” “He was thrown into the prison of Ste. Pelagie, you told me.” “‘But he escaped by choking a sacristan so that the poor man will long bear the marks on his throat. And the first thing 1 ‘knew he was high in_favor with th Marquis du Plessy, and Bonaparte spoke to him; and the police llu;hefl at com- plaints ‘lodged against him." ““Who lodged complaints against him?" “1 did, monsieur.” “But he was too powerful for you to touch?” “He was well abbe. srotectad. monsieur the He flaunted. While the poor e and myself suffered inconvenience and fared hard—' “The poor Prince, you say?" “We never had a fitting allowance, monsieur,” Bellenger declared aggressive- ly. “Yet with little or no means I tried to bring this pretender to justice and de- fend his Majesty’s throne." “Pensioners are not often so outspoken ln1 their dissatisfaction,” remarked the priest. I laughed as I thought of the shifts to which Bellenger must have been put. i&bb? e%d;ewonh with merciless dryness nquired: ‘‘How were you able to post to Mittau?" ““I borrowed money of a friend in Paris, monsieur, trustlnf that his Majesty P @ would requite me my services.’ “But why was it necessary for you to post to Mattau, where this pnunder would certainly meet exposure?’ “Because I discovered that he carrfed with him a casket of the martyred ‘(]}ue!e’;fs Jewels, stolen from the Marquis u essy."”" “How did the Marquis du Pl possession of the Queen's jcwda‘”‘"m 'gh!n:hl ;lo n]ot knovlv‘. ‘But the jewels are the lawful property of Madame d‘Angouleme. He must have knt;wt'll: theg" Tould be setzed.” = oug! necessa; 0 dence against him; monsteure s T °V “‘There was little danger of his himself upon the court. Yet you are rBatl!laer to b&sfl&mandod than ellenger. s pretender kno were in Paris?” b . W . I took s to ki him from knowing how I :::ghed lll:l." “You say he flaunted. When he left Paris for Mittau was the fact generally reported?” “No, monsteur.” ‘“You learned it yourself? “Yes, monsfeur.” “But he must have known you would P tett witn secrecy “He left great , monsieur the abbe. It was given out t he was m'gslga soln.‘:l to coml'.ry)i: r t made you su t ‘was ing to Mittau?" g o “He hired a strong post-chaise and made many prej tions.™ Pl"But :jmn‘: t.n fflugg.;;l; Marquis du ess Iscover e rol wh’ didn’s he lf)(;h;' and dtake (thnl thief?”" N ‘“Dead men don’t follow, abbe. The Marquis du Plu"m hmmm? on his hands, and was kill day after this Lazarre left Paris.” Of all Bellenger's absurd fabrications this story was the most ridiculous. I laughed again. Madame a'Angouleme fook her hands from her face and our eyes met one finstant, but the idiot whined g:: :‘.‘ gut:‘. She shuddered and covered The priest turned from Bellen; to me qmu};led.‘ fair-minded uyn-lm":nd in- ““What have you to say?” oll lmhd a 'r;at deal to say, nly hearer I expected to convince was my sister. If she believed in me I did not care whether the others belleved or pot. I was going to be; George, the moun an Bellenger’s fear of me. and his Loufs Philippe told him the larger por- tion of the money sent from Europe was given to me. Facing Marle Therese, therefore, Instead of the Abbe Ed orth. I spoke her rame. She looked up once mere. And mstead of being in Mittau, T was sud- denly on m:h?‘lcl::z- at thnmilvlln! o cape, ¢! . stretched beyond a multitude M flaming eyes, mouths, coarse lips, the heads orna- though the luminated by torches, mented with a thre thing K into the caps. My hand m::hd“:fn for llrpmrt. and met the clip of my mother’s fingers. I knew it she was Lowering between and a ‘earless palpitat itue. The - {lish, roaring mob s above an forced, ery—* the Queen!" n'anulmh-.