The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, April 14, 1901, Page 9

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

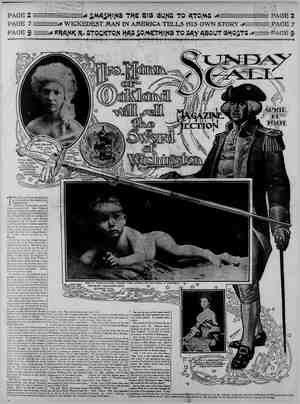

x = \u \ W\ R. FRANK R. STOCKTON oc- cupies so unique a fleld in American literature that it has puzzied many eminent critics to classify his work. I read, some while ago, an article by Ed- Gosse, who described Mr. Stock- outlook on life and people as a “literary squint.” s criticism was, of course, of the he saw him in his books. If Ed- e had selected a nearer view of an author, he would have seen with & pair of deep set, warm, eyes that gleamed with intelligent, lighting up & very serious nela in its quiet re- ous force and mental en- humor almost choly ne m with two such eyes “‘squints’ gh the originality of his readers “squint.” abt, the trouble with alth meeting of the Authors' New York, Richard Watson f a young writer to propose & con- ¥ every month. kind stories do You propose \der. like ‘The Lady or an attractive idea. fledgling, and hiw rded in the office as an m in thelr reception “squint™ \ asked take & knowledge. It is impos- eblle look at Mr. Stookton without a st irritating, suspiclon that the answer to his lit- n, “The Lady or the alm ne knows ask him about it he looks avel into & far off dls- nd in his slow, n, his eyes e of myster easy er of speech he says: know which it was. I mnever ew whether it was the Lady or the I'd like to know my- er Honestly, 't you easily have extended the story and gratified our curlosity?” “How could 1? The story didn’t have much over fifteen hundred words, and when I got to the end of it I just stopped, hat's ts success was a great sur- prise to me. When the opera was pro- duced taken from the story a lady whom 1 knew suggested that the last act could reveal Tiger one night and the Lady the ne: ately, so that the audiences would never know which they were going it the theatrical folk wouldn't wces, and they never did to see, b take those c! Theatrical literature is something which the mekers of literature understand bet- 2 they are reputed to understand 1gh Mr. Stockton expressed no rd play writing, et way that he in- » write a play some day. Literary Ethics in Humor. ¥ h my book ‘Squirrel Inn' was I can claim no greater dis- achlevement than hav- he said, and he tly on his lap and f of that event, s the author of most dramatized ries, eoccrding to modern tenets ere is @ suggestion In this view of matter whether the gaping wounds the st ng process of dramatizers ag to literature are not separating terary men from the theater en- ry bumorist would never say , as the comedians say of and their plays, “It is to and 1 have gyen found that the have written representative mor nearly all have the same ainst the broad grin and the terous laugh that imply deliberate hu- x ose on the part of the author, ely, silently, of course, on of being funny men in the ho strive to be funny at of literary ethics. When I Mr. Stockton that he was a humorist he %ooked at me and was doubtful whether ation was complimentary or clves no doubt, I suppose my morcus,” he said, his face nd thoughtful than a pro- sor of science, “but I don't know that ers are different frem oi1dinary t they do anything that or- ary people would not do in certan sit- sations. I always try to retain simplicity »f characterization in any dllemma of plot.” “How 8o you work out these peculiari- 7ng,u:nt]y the tary to what I am dic Indi fference of ™Y ties of human nature?’ I asked, bravely, He paused a moment, shifted uneasily in his seat, evidently uncertain whether to make the confession or not. “I live in the country—I love the coun- try,” he said at last, and there was no humor in the sincerity of his sentiments as he went on: ““The characters in the country are more individual; they have more room to move ebout in than in the city. I never took much interest in the city people, perhaps because I never cared much to under- stand them. It seems to me as though the townsfolk are all more or less alike— they imitate each other so much. Not that country people are more eccentric than the rest of the human famuy. I don’t mean that, because I don’t find them #0, but I believe in native conditiors that can be easily traced and explained and understood.” He hesitated a moment, for he talks slowly, because he thinks too rapldly, rerhaps, and then said: “It's a hard mat- ter to trace the native in a big elty; loses track of himself somehow or other in the crowded procession of town life.” A Reportorial Experience. he “Have yqu never lived in a elty™ I asked. “Yes, T worked on a newspaper in Phil- adelphia once, and"'—he stopped short, un- certain whether his reminiscence of news- paper work in Philadelphlia would be re- speettully received by a New Yorker, “You were say{ng you lived in Philadel phia,” 1 eald encouragingly, "“Did you ke 1t “Well, T wasn't what you would call a reporter,” he continued, genulnely apolo- getic of that fact, “but I used to write on different subjecta.” “Did you ever go out on an assign- m “Once—once only, and I covered myself with glory, if you will allow me to say so. 1 was told to get a report of a horti- Itural and florists’ exhibit made at a great fair that was held in the city for some big charity. Oh! it w fair—a whole square of Ph closed in glass. Well, I strolled in and saw at once that to make an exhaustive report of the matter would need an extra press in the printing department of the paper and a knowledge of Latin beyond any compositor ever born.” “What did you do?” “I went quietly to every exhibitor and asked him to write me a careful report of the technical history of his own exhibit. The next day I collected my stack of amateur manuscripts, containing expert descriptions, ani wove out of the mass an article so learned and complete on the subject that a man who was sent to re- port the matter for a horticultural paper lost his job, and they used a clipping of my report. Oh! yes, the editor knew that I loved the country and flowers and trees, and so on, and figured that I was the best man to handle a horticultural article.” “In the realm of imagination you have no such expert testimony to draw upon?” I said. ou mean in fairv stories?” “Yes, that is one phase of fiction for children.” I suggested. “I don't write for children,” he sald: “1 write for adults, or at least for peopls who can read and wrile!” “Aren’t felry stories written for chil- dren?” “Some of them have that distinction among generous but misguided parents, I always felt that the writers of fabhy stories were too prolific with fairy wings. It never seemed natural or reasonable that even fairies should be always spread- | ing their wings and leaving every onc else in the story standing around feeling sma'l and inefficlent In their infericrity o® legs | and arms. But, of conrse, these remarks apply only to my style of fairfes.” “Fanciful subjects usually take poets’ license!” Isaid. “‘Of course, I don’t mean to suggest that fancy should be banished, but there are S0 many things that have a better right to wear wings than fairfes. For instance; one can quite imagine a fairy livery sta- ble, where one can hire a bee, or & swell pair of high-stepping butterfiles, har- nessed to a comfortable wagon made of honeysuckle to take tho air in."” How promptly and essily, without any attempt at manner to display the matter he conveyed, did his mind travel Into the fantastic world! I told him this, and in- ferred that one of the most remarkable features of his stories was their fantastic touch. It transpired trat he had always had it, even from the very first story he ever wrote. “What was the nature of the first serial tating, Jiscaumgg"s’z,, % ~ Sscre "N\ Sorry thewr — story you ever wrote?” I asked him. “Let me see—oh, yes, now [ remember," and with the cffort of recollection camw a relaxation of arms, iegs and body, tor- gotten by the mental absorption of the man. “My first story was written for a maga- zine published before rne war, and after the war broke out was never heard of again. I never saw put three parts of it in print, when the war came and swal- lowed the magazine and the rest of my manuseript. I've often wondered what, became of that storv.” “What was it called?”’ I asked, break- ing the pause that followed. “I called it ‘A Story of Champagne,’” he said. “It was historical in a way. It was a tale lald in the French province of Champagne. The only feature that I re- member of it was a situation that seemed very pathetic. Some one had left a for- tune in his will to some one else and the heir to this fortune was, of course, de- prived of the will by the villany of some- body or other. This young man was very anxious to discover the will, and hunted ceaselessly for it. It so happened that at the very moment when the will was belng N ] pever knew A Lhether it was the Ylve elwoys felt or ghosts, rofe’ssion rot, half apprtuated THE SUNDAY OCALL. I3y »” 4 T (0 Lo dont writ sard burned by the villaln he chanced to be passing the house where this deed of de- struction took place, ard some charred portions of the burned documents fled up the chimney and dropped on his face.” “Did he recognize the will?” I asked eagerly. “I don’t know exactly how it was done, but he brushed the charred paper off his nose with his thumb aad forefinger, incl- dentally losing forever a great fortune in the smudge on his face.” He concluded this reminiscence in a sad, soft volcs, without a smile on his face, then got up and walking over to the window, looked solemnly out upon the Broadway cabie line. Ghosts That Are Out of a Job. “What about ghost stories? Do you be- HE field of the camera {s now prac- tically unlimited. The photographic lens is now turned upon other worlds and it reveals hitherto hidden mys- | teries of the heavens. tely it has been “ directed to submarine d8ths, and now we | have the strange creatures of the sea and river as they live and move in their na- tive element. In this latter regard Dr. R. W. Shufeldt of this city has demonstrated the won- | derful possibilities of photography under water. Dr. Shufeldt, who is well known as a scientist and writer, has co-operated with the Fish Commission in his labors, and has reached, as intimated, most as- tonishing and encouraging results. Dr. Shufeldt’s subjects were taken in the aquaria of the Fish Commission's build- ing while floating idly in the water or swimming about for exercise or in search of food, 0 that the pictures represent the fishes as they habitually live instead of under such extraordinary conditions as leaping into the air after a fly or pro- jecting themselves from the water to es- cape a pursuing ememy. The fish with which Dr. Shiifeldt seems to have the best luck is the common fresh water sunfish, known to many outside of the sclentific world as “pumpkin seed.” The Intricate markings and mottlings of the species, together with their grouping, are beauti- fully displayed n several of the doctor’s photographs. * For fully two hours on an ‘lshotographs of Fishes Swimming in T intensely sultry afternoon,” writes Dr. Shufeldt, “I was obliged to walt before one of these specimens came into the proper place to be photographed.” The result, however, has repald the trouble, as the pictures are as perfect as if taken through the medium of air in- stead of water. A very realistic plcture of the large-mouthed black bass is among the finest examples. Other photographs made include those of the naked star gazer, lying on its side and gazing up- ward witk that rapt expression so char- acteristic of its kind; the brook trout, a very fine picture, and the catfish, very well taken. From a photographer’s point of view perhaps the most interesting of the plct- ures Dr. Shufeldt has taken thus far is that of & school of rainbow trout, 450 strong, taken while swimming. It is by no means a perfect photograph, many of the fishes being out of focus and others being so shadowed as to be hardly dis- cernible, but not a figure exhibits any blurring from movement, and it is doubt- ful whether any other photograph extant shows so many living fish in one plate. Touching upon the matter of fish pho- tography, Dr. Shufeldt says: “To one having but little knowledge of the use of the camera it would appear to be a simple matter to photograph under such apparently favorable conditions, but such is by no means the case. In the first e at all,’ JStockton simply and 1its A : had heard it lleve In ghosts?” I asked. “I wrote a story once called “The Trans- ferred Ghost,” which answers that ques- tion in & way. I've always felt sorry for ghosts. Their profession is not half ap- preciated. It was partly this sympathy 1 feel for the melancholy destiny of ghosts that made me write the story just men- tioned; it was my appeal in their behaif.” “An appeal to encourage our sympa- thies for them?” “Somewhat. I always felt that there must be quite & number of ghosts out of a job, 5o to speak. Ghosts that we never heard of, because they have not been as- signed to haunt any one in particular. My transferred ghost was one of these unfor- tunateb. He had no position; he was walt- ing for some or to dle, S0 as to find a her Native Element place, in most Instances, the incessant, rapid and often erratic movements of the fish themselves have to be taken into ac- count; the aquaria being large, we have, in the second place, the difficulty of prompt foeusing to contend with, due to the latitude enjoyed by the smaller and more active forms; thirdly, there is the question of reflection, and this, taken in connection with the light, is a gerious problem. Reflections are especially trou- blesome, as the glass fronts of the aqua- ria receive them from all directions, so that after focusing a careful study of the image upen the ground glass will show these reflections, not only from some of the other aquaria, but possibly the pho- tographer and his camera besldes. All this must be carefully guarded against. ““The camera employed upon this occa- slon was an old model Blair touragraph, with 2 Voigtlander lens (No. 1), an in- stantaneous shutter of the Low pattern, Seed's gllt-edged plates (5x8); I used stops as any special case demanded. A tripod is absolutely essential to success in_ this kind of work. The instrument was set up in front of one of the more favorable aquaria and focused upon the part de- sired and an inch or two beyond the sur- face of the glass. An armed plateholder was inserted in_place of the ‘snap’ set. Patlent waiting for an exposure when the fish swims to the surface where you want it is necessa Care must be taken in drawing or pushing back the slide of the plateholder.”—Washington Times. the Prince of Wales, 1 was_turious to what wonld offend him.” tirued, 3:tlc 0T toncluded this remimiscence; in a_sad seft veice. offended & now place to be transferred from one abode of human crime to another. There can’t be a very extended fleld of labor for ghosts, industrious as they are when they do get & job, as we know."” It it were possible to describe the dry, quiet monotone in which Mr. Stockton un~ ravels these whimsical turns of his mental machinery, the pecular originality of his stories would seem to be the most natural result of his logic. We only get a blurred reflection,- at best, of an auther in his books; it requires a personal contact with a man to discover the true senses of his nature. I asked the question. “It is quite natural that you should ask me that,” he said; “every one does. I could not explain the method definitely. I use different lenses in getting my imag- inative focus. I'm like a photographer who puts up his camera in a crowded street, and, watching the procession as it glides on in shadowy semblance across his machine, instinctively walts till he sees a suitable picturs, and snaps it,” he sald, dreamily. “I don’t suppose he would at- tempt to record the jumble of objects about him, but his discretion, his taste, his particular eye select and approve.” “Do you write rapidly?” I asked. “I don’t write at all,” sald Mr. Stockton, *| stmply. “I know better!” I said. “Actually, literally, T don’t write at all 1 dictate everything that I sign. I prepare every page of my siories mentally, even to the title, and my secretary, having tak- en it down in shorthand, reads her motes to me, then reads the page when it is typewritten, and I never look at the words 411 T recetve the proof from the printers.” “In that way you carry the story with you everywhere all the time?” “No. I go into my study or sit on the porch of my house from 10 to 1 in the morning. I give my secretary something to read and I begin to dictate when the spirit moves. I have a hard time the first few days with a new secretary. They seem to be =0 interested in watching me and reading what I dictate. After a while they don’t care at all what I write. Fre- quently the indifference of my secretary morist estion: flnswer.' ell, ] wasn't what yor'd call a reporter, z enuInely ap¢ that fact = but Tused 1o write',on a’x/fer- ent swhrects’ scloses Some. £ the/Mbthods of a Literary 4 Jhe Oft~72€/oeated sz Ipvariable \ \ » *he con~ olo~ to what I am dictating discourages me. Then I try to arouse her by doing some- thing sensational. 1 suddenly make the hero stick a knife Into his sweetheart just to see If the secretaiy s really lost to all sensibility. “Only the other day T was telling Mr. Eggleston that 1 had done something I had never done before; I had interested my secretary.’ Love Interest Not Easential. “Have you always diotated your storiea™ “No; T couldn't do that at first, It's & development. My wife used to help me at first." “Which must have given a love interest to the atorte: 1 sugwested “Of course; but I don't belleve that the love interest is such an essential quality a8 many authors would have s belleve. It 1a & miatake to fores Into a atory & love affalr, for it Is always more or less ob- vious to the readen™ Mr. Stockton makes fiylng visits to the elty during the winter at short interval but he never doss any work except at his home in the Ehenandeah Valley, near Charlestown, W. Va. “We took a furnished house In Wash- ington once for a month,” he sald, some- what sorrowfully I thought, “but that is the only time we have ‘kept house’ in & elty.” “You received no inspiration to writs a soclety novel, as a result of the expert ment?” I asked. “No. The smart set are not In my lne. I do have society people in my books, but they are not remarkable in any distino- tion for that fact. I live on property that belonged to Washington, left in his wil to his nephew, Bushrod Washington. The road along which George Washington passed with General Braddock runs through my place.” “Then we may look for & Colonial story 7" “No. I'm purely contemporary. The novel I am working on describes this lo- cality and occurs there, but my charse- ters are not coples of my neighbors, how- ever much they may inspire me.™ ©Of all the plays accessible in New York, I was anxious to know which play would attract Mr. Stockton, and I asked him. “I dom’t go to the theater much, al- though I am very fond of it.” “What did you go to see?™” “] went to see ‘A Royal Family,’ be- cause I had heard it offended the Prince of Wales. I was curious to see what gave him offense.” *Why?" I asked abruptly. “Pecause I offended him once myself, or at least the English peopls, quits unin- tentlonally. I wrote a story called “The Great War Syndicate.” It was purely a fictitious description of a war between this country and England. controlled by & huge syndicate, In which the English ‘were beaten. There was no bloodshed, either, no one killed, but one man, and he accidentally, because a derrick fell on him. It was merely a contribution to Anglo-Saxon literature, and not partisan in its intention at all. Last year I re- celved & request from London Punch to writs & story for it, the editor stating in his letter that I might choose any sub- fect 1 ltked, so long as it was not im- moral. I aid not find the instructions dif- ficult to follow. Since they had written to an American author for an American story I gave them one. It was In three parts, & tale of the Cape Cod people, and I called it “The Gilded Idol and the King Corch Shell'—T've not heard how it has succeeded.” Mr. Frank R. Stockton is a humorist who wears no badge of humor to identify him as a specialist He has written his- tories, school books and storfes, all in the proper balance of the dutles they wers born to perform. His father was a writer of religlous articles, and there is a seri- ous, almost ministerial solemnity about him that adds a personal charm to his quaint fashion of sceing and saying things. His satire is always considerate, and his humor is ofgAmerica, for Amer- fea. PENDENNIS