The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, April 14, 1901, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

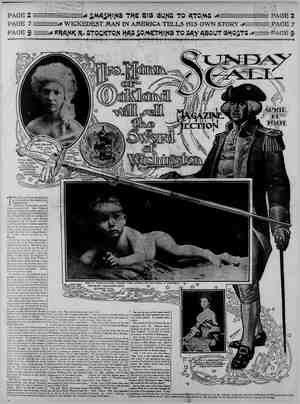

THE SUNDAY CALL. B OW to utilize the vast expanses of arid plain which characterize cer- tain portions of the section gen- erally designated as the “South- west,” is a problem that has long bafed the most ardent exponents of desert reclamation. True, thousands of acres of once utterly sterile land in vari- ous portions of the section referred to have, through irrigation, been trans- formed into regions of surpassing fertil- ity. But such possibilities are compara- tively limited, while beyond the friendly water zones there stretch away immense tracts which, a familiar Western proverb declares, “Will raise nothing but sand and cactus” So long and persistently has this idiom been bandied about, that it is scarcely a wonder the last mentioned of the two features excepted should come to be pop- ularly regarded as a product of absolute- 1y no intrinsic worth. The idea, however, ie deplorably erroneous, and so long as it continues to prevall immense acres, capeble of ylelding princely revenues, must remain in unclaimed idleness. That substantial profits may be realized from the cultivation of cactus and kin- @red desert products is being demonstrat- ed In various other countries where the conditions affecting thelr growth and the possibilities of practical utility are alike inferfor to those offered by this, their native clime. The species of cactus In- digenous to, the wilderness districts of New Mexico, Arizona and Southeastern ornia are upward of 500 in number, e most common of which are those L JosE DEQLIVARES N N AN R known as the Cactus Giganteus and Op- tunia Tuna. The former of these, as indicated by its name, is a monster variety, the elongated ribbed branches of which reach to a height of from 50 to 60 feet. The general aspect of this desert prodigy is grotesque in the extreme, its lower branches rear- ing themselves aloft with symmetrical stateliness, while those above reach down- ward and outward like the serpentine arms of a mammoth octopus. Anbther specimen of the giant cactus presents the appearance of a single towering col- umn, with perhaps a solitary abbreviated branch near the apex, causing it from a distance to closely resemble a telegraph pole. The commercial value that attaches to this specles of cactus is its adaptability to the manufacture of paper. Recent ex- periments with the pulp ylelded by the tough, fibrous element so prevalent in its constituency have demonstrated that a superior grade of paper can be produced therefrom, and, provided an adequate supply of the material can be developed, at & much lower cost than from ingre- dients commonly in use. The materials at present entering most extensively into the manufacture of pa- per in America are waste cotton and cer- tain wood fibers. The supply of such in- gredients, however, is by no means inex- haustible. According to the latest sta- tistics, there are at present operated in various parts of the United States no less than 1231 paper mills, with a daily pro- ducing capacity of 20,936,180 pounds of the perfected ware. This enormous produc- WORM THAT IS CONSIDERED A CHOICE TABLE DELICACY NE of the queer little animals of ( Madagascar, which is highly re- u . ¥ the natives as a table v, is the wormeater Tenrec, etes Ecaudatus, of the family of Cen- idae. His habits are strictly nocturnal. e his cousin, the mole, he dotes on and he has the family nose re- markably developed. There is little or no chance for & worm when T noses him from above; down through the earth like a knife into butter goes the proboscis, and subsequent proceedings interest the worm no more. The Tenrec has an anclent pedigree, and is one of the primitive types of mammals for which Madagascar is famous. He is the sole representative of his family, and ec e is especlally remarkable for the total absence of any tail (whence the name Ecaudatus), and for a unique arrange- ment of teeth, four upper tritubercular molars. This, say the naturalists, with his singular skull, proclaims his relation- ship to the marsupials of Australia and America, another family of extreme an- tiquity. The Tenrec is a spiny, bristly and hairy creature, of a general yellow- ish brown color, a foot or so in length, and takes things easy for half the year, hibernating below ground. Then it is that the worm has his re- venge, for just as Tenrec roots up worms, s0 do the natives of Madagascar root up Tenree, and for precisely the same reason. | Roast Tenrec is, in fact, one of the speclal dishes of the Malagasy culsine. GROWUP oF DESERT PRoDUCTS. | cumstance, & = '{*@ tlon represents an increase of 298 per cent within the last thirteen years, and, con- sidering the rapld inroads made on our native supply of white pine and poplar, Wwhich at present constitute the most economical basis in paper-making, the ne- cessity of & supplementary material must eventually be manifested. The presen‘ growth of cactus on our great Southwestern plains, while exten- sive, is under existing conditions too scattering to form a permanent source of supply gs a paper producer, which cir- however, could readily be overcome by propagation in districts suited only to thfs and kindred indus- tries. The whole organization of this desert product adapts it to the endurance of continuous drought, while little or no earth is required for its support. In its wild state the mere falling of a detached bulb on the arid sands is sufficient to in- sure the subsequent appearance of an additional specimen, which matures with great rapidity. Hence the cultivation of immense forests of this future commodity could be accomplished with the utmost facility.. In addition to its ‘value in a purely mechanical sense the glant cactus produces in its season a delicious fruit, the crimson pulp of which the Indians of Arizona and New Mexico make into pre- serves of singular excellence, which fact involves a suggestion as to what mignt be accomplished, similarly, on a more ex- tehsive scale. . A more immediately resourceful deni- : CACTUS 1 PLoom™m zen of the desert, closely allled to -the glant cactus, but of an.order distinctly Ppeculiar to itself, is the Yucca Brevifolis, or yucca palm, as it is familiarly but erroneously called. This strangest of trees is principally indigenous to the great Mojave desert in Southeastern Cal- ifornia, where it thrives abundantly and with no other nourishment thn‘n is af- forded b the perpetual sunshine of that otherwise desolate region. In appear- ance the yucca resembles, somewhat, a scraggy oak, entirely destitute of ver- dure, but bearing at the end of each scrawny limb & curious growth of brist- ling spines. 3 The principal peculiarity of the yucca, however, lles in the character of its wood, which possesses no grain, but con- sists of an iIntricate and compactly inter- woven mass of wood fibers. It has for years been an established fact that these Liers are specially adapted to the manu- facture of a comparatively indestructible grade of paper, such as is popularly |- ized in the printing of bonds and other In- struments requiring extreme durablility. Several years since an English company made extensive preparations for the man- ufacture of yucca paper in Southern Cali- fornia, to be exported to the British Isles, but it was finally decided that the trans- portation and duties on the commodity, added to the cost of producing, was ex- cessive and the enterprise was abandoned. Had the venture been dominated with the i spirit of American perseverance and the product intended for home consumption there is every reason to belleve the un- dertaking would have proved a success. In justification of this bellef a local com- pany of only limited capacity is at pres- ent actively engaged in producing from yueca wood a tough flbrous material which {s utilized for such purposes as book binding, as a substitute for felt and for certain accessories necullar to the surgi- cal sclence. The product, when subjected to speclal treatments, is also extensively used as an artistic roofing, its flexible character admitting of its conformity: to the .antique tiling effect so popular in aréhitecture. The method employed in producing this specles of yucca paper is unique inits very simplicity, and consists merely in placing the log in & rotary veneer lathe, where by means of a keen horizontal blade it is literally drawn out into a sin- gle continuous sheet, which may readily be - cut with shears, but, singularly enough, will neither break nor tear. The cultivation of the Opuntia Tuna cactus’ in the sterile foothill districts, ‘where it vegetates most profusely, offers a novel inducement in the restoration to this continent of the valuable cochineal industry, for which our elimate is pecu- liarly adapted. The native country of the cochineal is Mexico, but through sheer neglect the industry has been largely ab- sorbed by South America and the Canary Islands, whence comes the greater por- .| southwest part of tion of the supply. In rearing the cochi- neal insect immense plantations of the Tuna cactus, frequently representing 50,000 plants each, are maintained. In addition to the revenue derived from the insects it nurtures, the'fruit of the tuna, which is borne in great profusion, ylelds a rich crimson pigment of considerable value commercially. This fruit, which is com- monly known as the Indian fig, or prickly pear, is highly esteemed as an edible in Southern Europe, the Canarles and Northern Africa, in which countries it constitutes: an impertant product. The fruit 1s also possessed of certain medicinal virtues, being freely administered as a cooling drink in the case of fever, and re- garded as a valuable remedy for the cure of ulcers. The hardihcod of the tuna cactus is quite as remarkable as that of its elephantine cousin previously referred to. In the countries where its commercial status is the highest, its cultivation is often successfully carried on in dlstricts that have previously been absolutely in- cinerated by volcanic action. In such re- glons the planting of the shrub is fre- quently accomplished by merely thrusting one of the thorny sprouts into a cleft of lava rock, from which portion it speedily develops into a thriving tree. On its na- tive American heaths the tuna, by reason of its more-congenial environments, at- talns to much larger proportions than anywhers else in the world, yet its valus in these parts has, up to the present time, been almost entirely overlooked. Probably the most valuable product tm. digenous to the American desert is tha maguey or agave, a plant partaking of identically the same nature and tenden- cles as the cactus. In appearance, how- ever, it s of an altogether different order and represents a series of flat, armored blades radiating from a central bulb. In numerous arid districts of Mexico the ma- guey is extensively cultivated, its leaves and bulbs ylelding a variety of products, such as spirits, cordage and textiles. Some {dea as to the immense profits de- rived from the culture of the plant in our neighboring republic may be had from the fact that its combined products often Yield the grower upward of $500 In gold to the acre. It is well known that this desert shrul will thrive with equal redundancy nortw of the Mexican line and although the bev- erage it yields so coplously might well be dispensed with in this country its other products, if sufficlently developed, could be rendered important adjuncts to our present resources. —_——————— Experts sent out by the British South African Company to inquire into the re- ported find of coal In Rhodesia state that the coal fleld is situated some 130 miles northwest of Bulawayo and is known to extend over at least 400 square miles. The seams vary from five to ten feet in width, and as the coal lies within forty feet of the surface it will be worked by means of Inclines instead of by shafts. Some of the coal compares favorably with the best product of'[he ‘Welsh mines. o PITIFUL story, albeit uncanny, comes from Oklahoma. It is a story of Indian bellef in spirits— or, rather, of one great Evil Spir- it. And it is laying waste the lives of many poor Indian mothers. The Cheyenne Indians, who inhabit the the Territory, have been holding what they call “death dances.” They not only do this, but they have been killing their own children and doing other fearful things because they belleve that the Evil Spirit demands such sacrifice. The wrath of this spirit, they clajm, has fallen upon their tribe the past month. This, of course, sounds barbarous and absurd to white people, but the redskins have their bellefs about the Spirits, and + TERRIBLE DEATH DANCE OF CHEYENNE INDIANS do what they consider is the best under the circumstances. Mrs. Anna Yellowbear, the wife of a prominent medicine man, went blind and insane of grief from the death of her baby girl, which was buried some three weeks ago. Her afflictions were taken to mean that all the chiidren of the tribe must dfe, and several were smothered to death by their mothers and buried in treetops. Bands of how redskins gathered around these graves and moaned and prayed to the Great Spirit to save thelr tribe. Notwithstanding this, the children continued to die, and many of them wers buried in one large grave. Diphtheria is the cause of most of the deaths, but the Indians think the Evil Spirit demands the sacrifices.