The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, January 29, 1899, Page 21

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

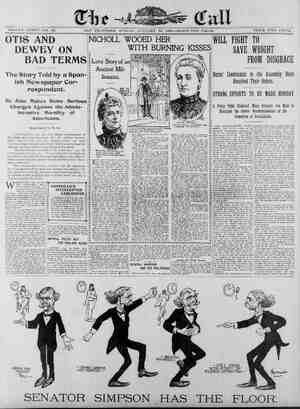

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, JANUARY 29, 1899. 21 SRR N : i e T Bk e TAPESTRY \WORKER AT HIS FRAME: .. were all Gobelin tapestry workers, and now my son and my grandson are follow- emarkable,” I said, “‘but Gobelin topestries to do with Genevieve Green. Te have much to do with the Bievre, safe to say AST May I spoke before my peo- ple at home on the subject of Imperialism. 1 took my title, as I take now my text, from Kip- ling’s “Recessional,” the noblest hymn of our century: “Lest we forget. For {t seemed to me then, Jjust after the battle of Manila, that We might forget who we are and what we stand for. In the sudden intoxica- tion of far-off vietory, with the con- sciousness of power and courage, with the feeling that all the world is talking of us, our great stern mother patting us on the back, and all the lesser peo- pies looking on in fear or envy, we might lose our heads. ® But greater glory than this has been ours before. For more than a century our nation has stood for something higher and nobler than success in war, something not enhanced by a victory at sea, or a wild, bold charge over a hill lined with ma: .ed batteries. We have stood for civic ideals, and the greatest of these, that government should make 5 Y they could men by giving them freedom to make e Pt : themselves. The glory of the American 3 ' he sald, blowing Tepublic. is that It is the embodiment I was de of American manhood. It was the dream of the fathers that this should always be so—that American govern- ment and republican manhood should be coextensive, that the nation shall not go where freedom cannot go. Colonial expansion is not national growth. By the spirit of our constitu- tion our nation can expand only with the growth of freedom. It is composed not of land but of men. It is a self- governing people, gathered in self-gov- erning United States. There is no ob- jection to national expansion where honorably brought about. If there were any more space to be occupied by American citizens, who could take care of themselves, we would cheerfully overflow and fill it. But colonial ag- grandizement is not national expan- sion; slaves are not men. Wherever degenerate, dependent or alien races are within our borders to-day, they are not part of the United States. They constitute a social problem; a menace to peace and welfare. There is no solu- tion of race problem or class problem until race or class can solve it for itself. s of history very rarely re is no diversion in sting 1, forgotten pidated r I ex- e. “A river I have never bout for some one to in- a corner brass- younger of tune was sure ave to travel “No, I don't b If it were about tapestrie bit ins Ge nd my the for the first s pipe from his mouth. he world more fa- t he was Napoleon I he could not have ex- Unless the negro can make a man of s reater pride or dignity. himseif through the agencies of free- continued, “my father, my dom, free ballot, free schools, free re- gra her and my great-grandfather ligions, there can be no solution of the It was yonder,” he sald, pointing! to a group of buildings, *‘that Jean Gobelin, in the days of the middle ages, established an institution for dyveing. Th arlet that he produced was the most wonderful that e world had ever seen. t, men had never known the real beauty of scar- let before the d of Jean Gobelin, and of the waters the mag qualities for turning th: Its appearance is certainly deceptive. It looks as though it could only turn things brown."” old man. The n proces ¢ Sievre, the but truly we are indek this little river for the first Gobe tries. Had it not been for the be durability of the coloring w Gobelin produced, the idea of makin beautiful pictures in wool would have been born. There are people nowa- days who declare that the Bievre never po: ed this quality; that it is all a played-out tradition, but I know that true. I had it from my grandfather, who learned it from his grandfath “And the tapestries are manufactured race problem. Already Booker Wash- ington warns us that this problem un- settled is a national danger greater than the attack of armies within or without. The race problems of the are perennial and insoluble, for titutions cannot exist where free nnot live. territorial The templated would not extend our institu- expansion now con- tions, because the proposed colonies are incapable of civilized self-government. It would not extend our nation, because these regions are already full of alien races, and are not habitable by Anglo- Saxon people. The strength of Anglo- Saxon civilization lies in the mental and physical activity of men and in the growth of the home. Where activity is fatal to life, the Anglo-Saxon decays, mentally, morally, physically. The home cannot endure in the climate of the tropics. Mr. Ingersoll once said that if a colony of New England preachers and Yankee schoolma’ams were established in the West Indies the third generation would be seen riding bareback on Sunday to the cock-fights. Clvillzation is, as it were, suffocated in the tropics. It lives, as Benjamin Kidd suggests, as though under deficiency of oxygen. The only American who can live in the tropics without demoraliza- tion is the one who has duties at home and will never go there. The freedom of Spanish America is for the most part miiltary despotism. It is said of the government of Russia that it is “despotism tempered by as- sassination.” That of most of our sis- ter republics is assassination tempered by despotism. Mexico, the best of them, is not a republic; it is a despotism, the splendid tyranny of a man strong and wise, who knows Mexico and how to govern her, a humane and beneficent tyrant. We shall find in Cuba all the prob- lems that vex Latin America. There are three things inseparable from the life of the Cuban people—the cigarette, the lottery ticket and the machete. These stand for vice, superstition and revenge. We are pledged to give self-govern- ment to Cuba. This we cannot do in full without the risk of seeing it re- lapse into an anarchy as repulsive, if not as hopeless, as the tyranny of Spain. Only the splendid apparition of the man on horseback could bring this to an end. The dictator may bring law, but not democracy. Its ultimate fate and ours is annexation. It is too near us and our interests for us to leave it to its fate, and to the schemes of its own small politicians, It therefore re- mains for us to annex and assimilate . for 90000903¢ 900000 “MARIE ANTOINEJJE AND HER GHILDREN.” The Picture That Is Being Reproduced in Gobelin Tapestry for By Mme. Vigee Lebrun. the Gzarina of Russia. over there?” T inquired, nodding toward the group of buildings. *I have intended a long time to visit this institution If T may enter I shall go to-day. “Yes, this is Saturday. It is open to- day to the public. If you hurry you will yet have time to see a good deal,” he said, leaning forward to look at the clock of the brasserie. “Very well, I will go, but first tell me if there are other families who have been employed at thls occupation threughopt Is generatons. our case & uniqyk one®” K he answered, “there ve been making Gobe- s for a longer time than my connection with nturies. You know it the institution by c is a great honor to be a Gobelin tapestry work We do not money for our labo! h ernment gives u receive very much but when we are old each a pension nd a house and garden and we pass our last days in peace. I have not taken a . but my son stitch for a number of y as s eded me and h son will suc- st be sure to look at the tapes- are making for the Czarina,” he thanked him and had in my ears, naturally at 1 sought was the which will be a x Faure. Two ars ago when the visited Paris craved a beautiful picture of sweet hung in the forsaken gal- It was Mme. Lebrun's Marie Antoinette and her If a young mother and a s said to have touched What e could the lery at Versailles. por rait of dren. Hers the picture Czarina to tea Que th Cuba, but not at once. We must take and do it in decency and or- s we have taken Alaska and Ha- We take Cuba, Porto Rico and Hawali, not because we want them, but use we have no friends who can :anage them well and give us no ouble, and 1t is possible that in a cen- tury or so they may become part of our nation as well as of our territory. American enterprise will flow into Cu- ba, no doubt, when Cuba {s free. It will clean up the cities, stamp out the fevers, build roads where the trails for mule sleds are, and railroads where the current of traflic goes. - Doubtless a great industrial awakening will follow our occupation of Cuba when we have taken away the barrier of: our tariffs. The Anglo-Saxon nations have cer- tain ideals on which their political superstructure rests. The great politi- cal service of England is to teach re- spect for law. The British empire rests on British law. The great political service of the United States is to teach respect for the individual man. The American republic rests on individual manhood, the “right divine of man, the million trained to be free.” The chief agency in the development of frée man- hood is the recognition of the individual man as the responsible unit of govern- ment. This recognition is not confined to local and municipal affairs, as is practically the case in England, but ex- tends to all branches of government. It is the axiom of democracy that “government must derive its just pow- ers from the consent of the governed.” No such consent justifies slavery; hence our Union “could not endure half slave, half free.” No such consent justifies our hold on Alaska, Hawaii, Cuba, Porto Rico, the Ladrones or the Philip- pines. The people do not want us, our ways, our business, or our government. 1t is said nowadays that wherever our flag is raised it must never be hauled down. To haul down an American flag is an insult to Old Glory. But this patriotism rings counterfeit. It would touch a truer note to say that wherever our flag goes it shall bring good gov- ernment. Take the Philippines or leave the: No half-way measures can be perma- nent. To rule at arm’s length is to fail in government. These islands must be- long to the United States, or else they must belong to the people who inhabit them. If we govern the Philippines, so in their degree must the Philippines govern us. There are some economists who intel- ligently favor colonial extension to-day because to handle colonies successfully must force on us English forms of gov- receive for all this evesight and patience? After five or six years of apprenticeship if the worker be more than 22 years of age he receives the equivalent of $180 or $200 a year. The veteran workers recelve ordinarily $400 a year, and the cleverest in the institution not more than $300, with $1000 for the superintendents. Of course the pension and the house for old age amellorate these conditions. The honor too, as my old man indicated, counts for much. Twelve or fifteen years of constant la- bor are at least necessary before one is considered an experienced worker and sufficiently qualified to labor on the finest tapestries. We wlll never have any Gobe- lIn tapestrles in America I thought when this last statement was made to me. To leave a man in a Government po- sition until he was qualified to do some- thing would be considered a sin crying out to heaven for vengeance. Imagine a Gobelin tapestry being executed under our system of position holding. A Dem- ocrat would, perhaps, be working on the nose of Marie Antoinette; a change of administration would oceur, out the Dem- ocrat must go and In would stalk a ruth- less Republican, who had never seen a tapestry, to finish the poor little nose. The principal pictures that are now be- ing translated into tapestry at the Gobe- lins and that all the world will be ad- miring at the exposition of next year are “Two Episodes From the Life of Jeanns @'Are,” by Puvis de Chavannes, the “Ex- ploration of Africa,” by M. Rochegrosse, and six subjects from the life of Jeanne d'Arc by Jean Paul Laurens. The Gobelin tapestries are beyond the power of money. The Government of France will not sell them under any con- ditions, but reserves them for the decora- tion of public bulldings or for gifts to Gobalin Tapestry Atelier on the Banks of the River Bievre, give her the original; it was not his to bestow, and so he promised her a copy of the picture done in Gobelin tapestry. The tapestry makers commenced the work at once, and although four persons have given their entirg time to it since, it is not yet more than half completed. So beautifulis the tapestry even thus in- complete that one longs for a few Czar- ina tears, those that were sufficiently ef- fective to precipitate such a presentation. If the tapestry can possibly be finished, it Is expected that it/ will be one of the attractions of the exposition of 190, where it will be exhibited before its presenta- tion. Can an artisan produce a work of art is a question that natura suggests it- self in watching the tapestry workers. The tapestri re surely wor the laborers as surely artisans, clever and skiliful in a remarkable degree but not art Bach worker fias his partic- ular corner, at which he stitches away without the slighest attention to his neighbor. He is seated always behind the frame, the picture that is being copled be- hind him; .thus he does not see either the model or the work that he is execut- ing—two inconveniences which there seems to be no way of rectifying. In the olden times the cleverest workers were employed exclusively on the faces and figures, others passed their lives with draperies, backgrounds, leaves and flow- ; but nowadays the much better sys- tem exists of training the young people to execute heads and flesh as well as ac- ories. The cleverest worker cannot ibly complete more than three and a halt yards in a year, while an average worker does not execute annually more than one yard. And how much do they ernment. A dose of imperialism would stiffen the back of our democracy. It is true, no doubt, that our standing in the world is lowered because our best statesmen are not in politics to the degree that they are in England. The rules of the game shut them out. But I believe that we can change these rules by forces now at work. Wiser voters will demand better representa- tives, but these must keep in touch with the people, acting with them and through them, never in their stead. For reasons 1 shall give later on I believe that to adopt British forms, with all their unquestioned advantages, would be a step backward and downward, The chief real argument for the re- tention of the Philippines rests on the belief that if we do not take them they will fall into worse hands. This may be true, but it is open to question. It is easy to treat them as Spain has done; but none of the eloquent voices raised for annexation has yet suggested any- thing better. We must also recognize that the nerve and courage of Dewey and his associates seem spent to little avail if we cast away what we have won. To leave the Philippines, after all this, seems like patriotism under false pretenses. But nothing could have in- duced us to accept these islands, if of- fered for nothing, before the battle of Manila. So far as the Phillppines are con- cerned, the only righteous thing to do would be to recognize the independence of the Philippines under American pro- tection, and to lend them our army and navy and our wisest counselors, our Dewey and our Merritt, not our poli- ticlans, but our jurists, our teachers, with foresters, electricians, manufac- turers, mining experts and experts in the various industries. Then, after they have hdd a fair chance and shown that they cannot care for themseives, we shouid turn them over quietly to the paternalism of peace-loving Holland or peace-compelling Great Britain. We should not get our money back, but we should save our honor. The only sensi- ble thing to do would be to pull out some dark night and escape from the great problem of the Orient as sud- denly and as dramatically as we got into it. As for trade, to take a weak nation by the throat is not the righteous way to win its trade. It is not true that “trade follows the flag.” Trade flies through the open door. To open the door of the Orient is to open our owne® doors to Asia. To do this hurries us on toward the final “manifest destiny,” the leveling of the nations. Where the barriers are all broken down, and the friendly monarchs. Under the old re when kings and palaces were the fashion in France there were more opportunities for the tapestry workers—there were more whims to grati However, one feels that it is well that these hands have not lost thefr cunning, for the days of kings and whims might come again. After visiting Fontainebleau and Versailles and Baint Germain, where these silent palaces are always ready for one receives an irradicable im- pression that France is half expecting the king to arrivé at any hour of the night. The swallow has a larger mouth in pro- portion to its size than any other bird. There is no part of the world which has such a black record for wrecks as the n ltic seas. The number in some averaged more than one a d est number of -wrecks recorded ear being 425 and the smallest 154. About 50 per cent of these vessels became total wrecks, all the crews being lost. Probably the most expensive dinner ser- : in the world is the Sevres service at vi Windsor Castle. It is said to be worth £150,000. This sum appears a fabulous one at first sight, but if we consider that at the Bernal and other similar sales sums amounting to thousands were pald for a pair of pieces of Sevres ware it is not so marvelous after all. e e Does anybody want to count a billlon? If so, Professor Wagstaff can tell him how long it will take. It is not an easy job—not the kind of thing you can do in a hurry. In fact, aceording to the pro- fessor, if Adam had begun counting as soon as he was created—allowing this to have been 6000 years ago—and had count- ed steadily through the centuries without dying, without sleeping, without stop- ping. at the rate of ‘“one, two, three” second, he would only have counted 648,000,000, which is 1ttle more than half a billion. 4 ANTIIMPERIALISM: BY DAVID STARR JORDAN. & world becomes one vast commerclal re- public, there will be leveling down of government, character, ideals, as well as leveling up. “We want,” some say, “‘our hands in Oriental affairs when the great struggle follows the breaking up of China.” Others would have “American freedom upheld as a torchlight amid the dark- ness of Oriental despotism.” We can- not show American civilization where American institutions cannot exist. But the spirit of freedom goes with its deeds. I do not urge the money cost of hold- ing the Philippines as an argument against annexation. No dependent colony, honestly administered, ever re- paid its cost to the government, and this colony holds out not the slightest promise of such a result. In fact, the cost of conquest and maintenance in life and gold is in grotesque excess of any possible advantage to trade or to civilization. Individuals grow rich, but no honest government gets its money back. But with all this, if annexation is a duty, it is such regardless of cost. But America has governmental ideals of the development of the individual man. England has no care for the man, only for civie order. This unfits Amer- ica for certain tasks for which England is prepared. But though one in blood with Eng- land, our course of political activities has not lain parallel with hers. We were estranged in the beginning, and we have had other affairs on our hands. ‘We have turned our faces westward, and our work has made us strong. We have had our forests to clear, our prairies to break, our rivers to harness, our own problem of slavery to adjust. ‘While England has been making trade we have been making men. We have no machinery to govern colonies well. We want no such machinery if we_can help it. The habit of our people and the tendency of our forms of govern- ment are to lead people to mind their own business. Only the business of in- dividuals or groups of individuals re- celves attention. Our representatives in Congress are our attorneys, retained to look after our interests, the interest of the State or district, not of the na- tion. A colony has no attorney, and its demands, as matters now stand, must go by default. This is the reason why we fail in the government of colo- nies. This is the reason why our con- sular service is weak and inefficlent. This is the reason why our forests are wasted year by year. Nothing is well done in a republic unless it touches the interest or catches the attention of the people. Unless a colony knows what g00d government is and insists loudly on having it, with some means to make itself heard, it will be neglected and abused. This is why every body of people under the American flag must have a share in the American govern- ment. When a celony knows what good government is it ceases to be a colony and can take care of itself. To do what England does we must take lessons of England's methods. Toward: the English system we must approach more and more closely if we are to deal with foreign interests in large fashion. The town-meeting idea must give way to centralization of power. We must look away from our own affairs, neglect them even, until the pressure of growing expenditure forces us to attend to them again more carefully than we ever yet have done. One reason England is governed well is that misgovernment anywhere on any large scale would be fatal to her credit and fatal to her power. She must call her best men to her service because without them she would perish. Our government must be changed for our changing needs. We must give up our whole protective system at the demand of commerce. I, for one, shall never weep at that. But we must abandon our childish notions that America is a world of herself, big enough to main= tain a separate basis of coinage, a free- man's scale of wages or a soclal order of her own. We must give up the checks and bal- ances in our constitution. It is said that our great battleship Oregon can turn about, end for end, within her own length. The dominant natlon must have the same power. She must be capable of reversing her action in a minute, or turning around within her own length. This ‘“our prate of statutes and of state” makes imposeible. We shall re- ceive many hard knocks before we reach this condition, but we must reach it if we are to “work mightily” in the affairs of the other nations. If we are to deal with crises in foreign affairs we must hold them with a steadier grasp than that with which we have held the Cuban question. The Spanish Peace Commission knows well that it is no empire with which it has to deal. An empire knows its own mind and never ylelds a point. As matters are now President, Senate and House check each other’s movements, and the State falls over its own feet. The question is not whether Great Britain or the United States has the better form of government or the nobler civic mission. There is room in the world for two types of Anglo-Saxon nations, and nothing has yet happened to show that civilization would gain if either were to take up the function of the other. We may not belittle the tre- mendous services of England in the en- forcement of laws amid barbarism. We may not deny that every aggression of hers on weaker nations resuits in good to the conquered, but we insist that our own function of turning masses into men, of “knowing men by name,” is as noble as hers. Better for the world that the whole British empire should be dis- solved, as it must be late or soon, than that the United States should forget her own mission in a mad chase of emulation. He reads history to little purpose who finds in imperial dominion a result, & cause or even a sign of na- tional greatness. Infinitely stronger for the cause of freedom, says Justice Brewer, “than the power of our armies, is _the force of our example.” We may have a navy and coaling stations to meet our commercial needs without entering on colonial expansion. It takes no war to accomplish this hon- orably. Whatever land we may need in our business we may buy in the open market as we buy coal. If the owners will accept our price it needs no im- perialism to foot the bills. But the question of such need is one for com- mercial experts, not for politicians. Our decision should be in the interest of commerce, not of sea power. We need, no doubt, navy enough to protect us from insults, even though every battle- ship, Charles Sumner pointed out fifty years ago, costs as much as Harvard College, and tLhough schools, not battle- ships, make the strength of the United States. Some great changes in our system are inevitable, and belong to the coursa of natural progress. Against these I have nothing to say. Whatever our part in the affairs of the world, we should play it manfully. I make no plea for self-sufficiency, indifference, or isola- tlon for isolation’s sake. To shirk the world-movements or to drift with the current would be allke unworthy of our origin, our history and our ideals. In closing let me repeat what seem to me the three main reasons for oppos- ing every step toward imperialism. First, dominion is brute force. To fur- nish such power we shall need a colon- ial bureau, with its force of extra-na- tional police. A large army and navy must justify itself by doing something. An army and navy we must maintain for our own defense, but beyond that they can do little that does not hurt, and they must be used if they would be kept alive. The other reasons concern the integ- rity of the republic itself. This was the lesson of slavery, that no republic can ‘‘endure half slave and half free.” The republics of antiquity fell because they were republics of the free only. for each citizen rested on the backs of nine slaves. A republic cannot be an oligarchy as well. Whatever form of control we adopt, we shall be in fact slave-drivers, and the business of slave- driving will react upon us. Slavery itself was a disease which came to us from the British West Indies. It breeds in the tropics like yellow fever and leprosy. Can even an imperial republic last, part slave, part free? . Meanwhile, the real problems of civi- lization develop and ripen. They care nothing for the greatness of empire or the glitter of imperialism. They must be solved by men, and each man must help solve his own problems. The de- velopment of republican manhood is Jjust now the most important matter that any nation in the world has on hand. We have been fairly suc- cessful thus far, but perhaps only fairly. Our government Is careless, wasterful and unjust, but our men are growing self-contained and wise. De- spite the annual invasion of foreign il- literacy, despite the degeneration of congested cities, the individual intel- ligence of men stands higher in Amer- fca than in any other part of the world. The bearing of the people at large in these days Is a lesson in itself. « . e The day of the nations as nations is passing. National ambitions, na- tional hopes, national aggrandizement— all these may become public nuisances. Imperialism, like feudalism, belongs to the past. The men of the world as men, not as nations, are drawing closer and closer together. The final guarantee of peace and good will among men will be not the parliament of nations, but the self-control of men. Whatever the fate- ful twentieth century may bring, the first great duty of Americans is never to forget that men are more than na- tions, that wisdom is more than glory, and virtue more than dominion of the sea. The nation exists for its men, never the men for the nation. “Th only government that 1 recognize, said Thoreau, “and it matters not how few are at the head of it or how small its army, is the power that established justice in the land, never that which established injustice.” The will of free men to be just one toward another is our best guarantee that ‘‘government of the people, for the people, and by the people, shall not perish from the earth.” Gad of our fathers, known of old— Lord of our far-flung battle line, Beneath whose awful Hand we hold Dominion over palm and pine,— Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet, Lest we forget—lest we forget! Far-called our navies melt away, On dune and headland sinks the firej Lo, all our pomp of yesterday Is one with Nineveh and Tyre! Judge of the Nations, spare us yet, Lest we forget—lest we forget! ~The New World.