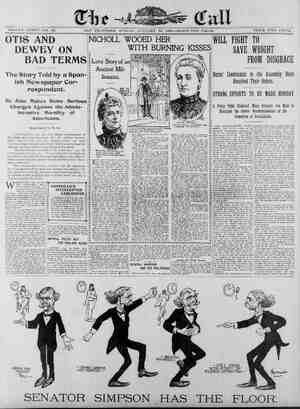

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, January 29, 1899, Page 20

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, JANUARY 29, 1899. e old proverb true? Will murder v Arthur Griffiths, one of 4 of prisons Ajesty's inspectors reful st of ¢ tnks that as a rule it wi Iges that there are nt exceptions to s of em ing as the e the endless to this side, w and or- torious in the ried patience, tion, 1dow g sagacity in fol- tlal capture—th r liately apparent. B Now and again, 1pidity run his head then the are not infallible. :ss oT overrun their open a door for escape. on Side of Police. and the com- tages of hunted and dent that the police have The machinery and or- modern life favor pursuit, nkage, the facilities of of the territory , the publicity that :l these are fcity is his > post and the wire; alls every- ternational ble bit of & eve: men and women le h people ar a There concealment, for avoiding dis- these are generally of a do- , not necessarily of a crim- = s who seek effacement do mnot sufficient_account the inquisi- mankind. the perpetration of some he culprit is unknown p, landlady, trades tor, raliway han i active amat to call in ion, or im- al circum- dissemination of news s undoubtedly se- he publication of ready decelvin, give out to ne 1 i to lul af ty by inti- )n_the wrong e newspapers as detectives Assistance of the Press. ¢t Lord Wil- r back 18 the man w a waiter. Only der he had of placing c iim a link that ier with the his capture mous murder of Mr. sed Briggs In ndon bound nd in the information that he hat at that maker's for ed Franz Muller, o former his. Muller t given his little a jeweler's cardboard box bear- ominous name of , Cheapsic ow, Mr. Death had ady produced the murdered man's which he said had been dis- by a man whom he be- There could now were He had started for America in a 1d was easily forestalled traced ng vessel detective officers, the jeweler cabman. and the Trifles as Clews. The smallest thing has often sufficed to establish a clew. Four letters, half a word upon a chisel, have led to the ion of its guilfy owner, A but- after a burglary has heen orrespond with those of a man for another offense, and the cvidence has been clinched by the fact that his coat lacked a button. In the famous Gervais case, in France, proof depended greatly upon the date when the roof of a cellar 'had been dis- rbed. This was shown to have been ne- arily some time before, for in the in- pund to c: in custody terval the cochineal insects had lald their eggs, which they only do at a par- ticular “season he Ineffaceable odor of musk and other strong perfumes has more than unce brought home robbery and murder to their perpetrators. An'interesting ocase is recorded in India, where in the plunder of a native banker an entire pot of musk, exactly as it had been cut from the deer, was carried off with a number of val uables, Musk is rare and costly, being obtained generally from far off Thibet. The police, in following up a band of da- coits, invided their tanda and were at once' conscious of an unmistakable and overpowering smell of musk. which was presently dug up with a number of coins of an uncommon currency, that were identified by t..e banker. The Murder in the Rue Mazarin. Tor close, hard, logical deductions from small Indications, growing gradually Into strong surmise and then into a certainty, the Frenchman Mace's detectlon of the famous murderer in the Rue Mazarin is better than anything ever invented by Gaboriau. On a January afternoon a ser- geant de ville hurrying home after being relieved from duty, was stopped by the owner of a small restaurant in_the Rue Princess with a horrible story. From the depths of the well in his courtvard he had fished up a package containing a human leg in_an advanced stage of decomposi- tion. The commissary of the quarter, M. Gustave Mace, then a young man on the threshold of a’distinguished detective ca- reer, was summoned to the spot. He made a close inv ation of the well and suc- ceeded in fishing up another parcel. The cover was a black glazed calico. Each end simply knotted, but the middie sewed with black thread. The re- al of this exterior covering revealed another covering made of a qart of a trousers leg in iron gray cloth. Inside of all was another human leg. Like the oth- er, which was probably its fellow, it was thin and shrunken and with little calf to it. There was only one tellt part of a sock bearing th 3 with a simple cross on each side of it, thus: x B X Now. ...y & week or two previous a hu- man_thigh bone had been picked up in the Rue Jacob. Subsequently a few mor- gels of human h had been fished out of the Sein nd the Saint Martin Ganal. Other Fragments Found. ent ran wila when fals of the Morgue reported that before Christmas a human _thigh, pped up In a common biue knitted \wl and bearing traces of having been a few days in the water, had been sited in the mortuary chamber. Then prietor of a riverside laundry Quay Valmy came forward with ¢ about midnight on Decem- nd tall h ngage n throwing or scattering some- thing in_the river by handfuls, They looked like scraps of meat. When inter- gated he had laughingly replied, “T am keen fisherman. To-morrow is'a holl- am balting the river for a big s sport.” . this date, the 19th, was just two ster than the discovery of the thigh ) in the old . Everything cold-blooded crime, and one natur Dr. Tardieu of the were those anced in A clearly , only recently healed, was i on one leg. Another fact had been shrewdly and quickly verified by Mace. The glazed callco cover, the peculiarly knotted ends, the stitching with black cotton—all these seemed to-him the handi- work of a tailor. From the conclerge he young seam- y glven up nd that decided that th drew out the fact that a Mile. Dard, had recent rtment in the hoi among her visitors was taflor who brought her occasional work ard who nsed to carry up water from her from the well. her Voirbo, the Tailor. rough Mile. Dard herself it was sub- o learvicd that the_name of the irrying tailor was Voirbo, She y his address, as she had ince his marriage, a few But she unhesitatingly Il information that she could. s Mace learned that tant_companion was a Bodasse, whose aunt, was__a bandage-maker, Mesles. The bandage- r ewed, described her nephew as a tapestry worker who had 1 money, but who was eccentric and 3 She had sen him for a s not anxlous, ot pp! en him previ for he had often dis The last time she had seen him was on Sunday, December 13, with his friend, Voirbo. “Pl e describe Voirbo.” “He is short, and generally wears a long overcoat and tall hat.” For the first time the scent was begin- ning to grow warm. Voirbo's trade and his intimacy with the old man whose name began with the initial “B” were good starting points. Mme. Bodasse was driven over to the Morgue. She iden fied all the fragments of clothing as hav- ing belonged to her nephew. She herself had marked the socks with the “B” be- tween the tw As to the scar on the leg, she remembered that her nephew had cut himself badly by falling on the sharp edge of a broken bottle. Voirbo and Bodasse. Mace traced Voirbo from his old address in the Rue Mazarin to a new one in the Rue de la Martin. From a woman who cleaned Voirbo's apartment more particu- lars were gleaned. She spoke of his in- timacy with Desire Bodasse and ex- pressed her surprise that the latter had not been present at Voirbo's marriage. Voirbo himself had appeared much an- noyed at this. “T wished him to be my principal wit- ness,” he had been heard to say, “but he has chosen to go off on & long journey the very day before the ceremony. There were differences between them in spite of thelr intimacy. Voirbo hated Bodasse for his avariciousness. Hs had begged his friend to hel’f forward his marriage by a loan of 10,00 francs, but the miser had refused. Here was a mo- tive for the crime if Bodasse was really the yictim. But Bodasse's apartments in the Rue Mazarin were fast locked. o concferge explained that he frequently lacked himself up for days or even Weeks suspicious fact. On arriving for work uite early on the morning of December % she had found her master already ug and dressed and the room swept out an arnished. It was not like Voirbo to do is own cleaning., More, he had actually taken pains to wash the floor. A part of the tiles were still wet and shiny. Then came another still more damaging reve- lation. The missing stocks were found in the new apartments to which he had re- moved on his marriage. M, Macptook him s s Nk g8 in steadily, so Voirbo resolved to kill and despoll him. The victim came unsuspectingly to his friend’s rooms and was taken from be- hind near the round table. A single blow from a heavy flatiron had stunned him, but the deed was not completed until the throat had been cut from ear to ear. Then the corpse had been dismembered and the fri ents gradually disposed of. Molten lead had been poured into the mouth and ears of the head, which, thus weighted, had been sunk in the Seine. The murderer, like our own Martin Thorn, “There Was an Immediate Change In Voirbo’s Demeanor. Terror Seized Him. He Could Hardly Keep His Seat, He Clinched His Hands, His Face Grew Ashy Pale, Fixed Upon the Water-Jug, Followed Every Movement and His Staring Eyes, of M. Mace's Hand.” She was sure that he was at she had heard movements and : windows during the last s decided to force the lock. The place was in perfect order, but there was a slight layer of dust on the furniture. The bed had n: 1 slept n. On the ce were the remai matches. at a time. home, as Above 2 lece were two paper candl one empty, the pther con- tainin candle. These boxes were of the at hold eight candles each. It would ar ore. that fifteen had been burned. As two of the matches had missed fire, this exactly corresponded with the number of burnt matches on the floor. In fact, the conclerge declared that she had noticed a light in the room just fifteen times during the previous six weeks. Wto Was the Visitor? Some one had evidently come there on that some one was probably e. The suspicion was in fact that a one-day clack ing with a regular tick, tick. Boda: hat—the only one he owned—his favorite walking stick and a large silver watch and chain, without which he never left the house, were found in the room. But a green pocketbook, in which Mme. Bo- dasse declared that he kept all his valu- and of whose secret hiding place was aware, had disappeared. A rap of p! paper, however, was found by M. Mace inside the watch. This con- talned a long list of numbers of securi- ties in Italian Government stock of the is- sue of 1861, all pay In the hopes that: the m: rooms might be caught on his next call, M. Mace organized a close watch and concealed two officers in an alcove of the principal room. But unfortunately they Bad “Rot been warned to look out for Voirbo, whom they knew, and befng fat- witted folk, they actually informed him of their surveillance. Thus he was put upon his guard. Foil- ed in this part of his scheme, Mace prosecuted his investigations into_ the character of the man. At the Rue Maz- arin_he learned that Voirbo, before leav- ing his apartments had paid his rent with a five hundred franc share of Italian stock of 1861, which corresponded with one of the missing numbers. Another Compromising Revelation. Voirbo's old servant revealed another by the $ne v B sy G He betrayed no anxlety, belleving prob- ably that he had left no traces of his crime. And now followed an extraordinary ne of the most brilllant bits of tive sagacity known to criminal an- A Brilliant Coup. M. Mace had been struck on his first survey of the apartment with a certain peculiarity in the room. The tiled floor sloped downward from the window to- ward the bed in the recess. He had also realized from the quantity and position of the furniture in Voirbo's time that the only part of the room in which there was room to move freely was #round a circular table which had occu- pled the center. He concluded therefore that if the murder had been committed there it must have been near that table, and further, that probably the dismem- berment had been performed upon it. ' aking up a jug full of water, e a slope on the floor. Now} if a bod cut up on this table the effu- sion of blood would have been great, and the fluid must have followed this slope. Any other fluid thrown down here must follow the same direction. I will empty this jug upon the floor, and we will see what happens.” There was an immediate change in Voir- bo’s demeanor. Terror seized him. He could hardly keep his seat, he clinched his hands, his face grew ashy pale, and his staring eyes, fixed upon the water-jug, {nllv;‘wed every movement of M. Mace's hand. The water flowed straight toward the bed and- collected beneath it in two great pools. The exact spot thus indi- cated was carefully sponged dry, and a mason summoned to take up the tiles of the floor. A quantity of dark stuff, presumably dried blood, was found below. The infer- ence was obvious. The blood had flowed from the body and percolated the inter- stices of the tiles, thus evading the was] ing of the floor and proving the in- completeness of Voirbo’s precautions, This terrible discovery effected in his own presence finished Voirbo. Then and there he made a full confession of the crime. Voirbo’s Confession. He had frequently begged of Bodasse to lend him 10,000 francs to help him to his marriage, but the miser had refused knew that the head was the part most recognizable and most valuable in estab- lishing the identity of the victim. It will be seen, indeed, that in many ways this crime resembles the Guldensuppe murder, but the story of its detection Is infinitely fuller of ingenious subtleties of infer- ence and deduction. Indeed, it 1s the most thoroughly repres ive story in the criminal annals of France. Volrbo foiled justice in the end. He committed suicide almost immediately on his reception at Mazas, the great celiular prison of Paris. ~He was waiting his turn to be inscribed on the prison register, when he tore open a long loaf he was carrylng under his arm, took out a razor blade and quickly cut his throat. Tact and Promptitude. The French detective often shows great tact and promptitude. One of them one day recognized a face without being able to put a name to it, and followed his man into a bus. “Don’t arrest me here,” said the other. “I'll_come with you quietly when we leave the omnibus.” It proved to be a prisoner who had escaped that very morning from the Prefecture whom the police officer had only seen for a mo- ment in the passage. Perpetual suspicion becomes second nature with the detec- tive; he has to be constantly on the alert, his imagination active; must readily invent tricks and dodges when the occa- sion demands. There is a positive order that an arrest must be made quietly, If possible unobserved, and not in any cafe, theater or public place. This obliges him to have recourse to artifice to entrap his prey. Fortunately, most criminals are simplicity itself, and readily give them- lves away. It is enough to send a mes- sage for the man wanted and he will ap- pear at the wineshop around the corner, bringing, say, his tools to do some Imag- inary job. Stupidity of Criminals. Crimmals continually ‘give themselves away'’ by their own carelessness, their stupid, incautious behavior. It is almost an axiom in detective work to watch the scene of a crime for the visit of a crimi- nal. He seems.drawn thither by an irr sistible impulse. The same impulse at- tracts the French murderer to the Morgue, where his victim lies in full pub- lic view. This is so thoroughly under- stood in Paris that the police station of- ficers in plain clothes are always among the crowd ever filing past the plate glass windows that sep- arate the ublic from the marble slopes on which the bodles are exposed. Numerous instances might be quoted in which an offender betrays his crime by {ll-advised ostentation, the reckless dis- plas' or expenditure of money after a F - riod of known poverty, the paradin around in the clothes or the jewelry o the murdered. A curlous instance of the neglect of ordinary precaution was that of Walnwright, the murderer of Hannah Brown, who left the corpus delicti, the damning proof of his guilt, to the pryin, curlosity of an outsider, while he went o in_search of a cab. Polsoners have repeatedly betrayed themselves bg their avowed study of toxicology. ne, a doctor, Castaing, ex- erimented on animals and kept a care- ul record of the effect of the poison he administered to his victims. The Marchioness of Brinvilliers, while await- ing trial, wrote a minute and detailed ac- count of her crimes. The polsoner Cas- truccio kept a careful record in his diary of the occasions on which he gave arsenic, and one of the facts brought against him was a demand for work on poisons pre- sented at a public library and signed in The Spanish pois- his own hnndwrilinfi oner Villamayor, who destroyed a whole family, laughed -openly at the doctors when they ignored the real symptoms and treated for gastritis the victims who were dying of poison. Ellison, the Bodmin murderer, went the very morning after the deed to have his hair and whiskers trimmed at the local barber’'s. The hairdresser noticed that his halr was ragged and that his beard was brown, while the hair on his head was fray. The murdered woman was found 0 have a handful of brown hair in one tlg‘hlly clenched hand, and of gray in the other. They had evidently been torn out in the flerce Slruggla for life, and they were positively identified as similar to those which had been cut and trimmed. Excess of Caution. The murderer's stupldity is sometimes &s clearly shown in the excess of precau- tion as in the want of it. Troppmann, the {outh of 19 who slaughtered a whole fam- ly, and whose intelligence was of such a high order that the prison chaplain celled him a genius, was_yet foolish enough to make a drawingy or plan,’ explaining exactly how the murder was committed bg Kinck, whom Troppmann accused of the murder. He described the scene of the crime so ac- curately that it was concluded he must have been there himself, and thus strengthened the suspicion against him. ‘The suggestion that death has been caused by suicide is often attempted, but hllal& fashion that provides its own de- nial. The fact of the knife or weapon being held looselh' must generally defeat the object of the murderer who places it in the victim's hand. As a rule, the weapon after suicide is tightly grasped. The force necessary for the act is continued, and passes into what doctors call the “‘cadav- eric spasm’; the hand becomes rigid, the bold contracted and clenched. octors are not quite agreed whether the mur- derer can or cannot create this effact. Many affirm that the hand of a dead per- son while still warm {s pliant and eannot be made to grasp anything so tightly as the muscular contraction which comes on at the last moment of life. On the other hand, it has_ been shown that if the weapon is held long enough and the fin- gers have been pressed around the imple- ment, it becomes more or less fixed when the second stage, that of rigidity, is reached. Jack the Ripper. The outside public may think that the identity of “Jack the Ripper” was never revealed. Major Griffiths acknowledges that go far as actual knowledge goes, this is undoubtedly true. But the police, after the last murder, had brought their inves- tigations to the point of strongly suspect- ing several persons, all of them known to be homicidal lunatics, and against three of these they held very plausible and rea- sonable grounds of suspicion. Concern- ing two of them the case was weak, al though it was based on certain colorable facts. One was a Polish Jew, a known lunatic, who was at large in the district of Whitechapel at the time of the murders, and who, having afterward develaped homicidal tendencles, was confined in an asylum. This man was sald to resemble the murderer by the one person who got a glimpse of him—the police constable in Mitre Court. The second possible crimi- nal was a Russian doctor, also_1 ne, who had been a convict both in England and Siberia. This man was in the habit of carrying about surgical knives and in struments in his pockets; his antecedents were of the very worst, and at the time of the Whitechapel murders he was in hiding, or at least his whereabouts was never exactly known. The Probable Culprit. The third person was of the same type, but the susplcion in his case was stronger and there was every reason to believe that his own_ friends entertained grave doubts about him. He was also a doctor in the prime of life, and belleved to be insane or on the borderland of insanity, who disappeared immediately after the last murder, that in Miller's court, on the 9th of November, 1888. On the last day of that year, seven weeks later, his body was found floating in the Thames, and was said to have been in the water a month, The theory in this case was that after his last exploit, which was the most flendish of all, his brain entirely gave way; and he became furiously insane and com- mitted sulcide. 1t is at least a strong pre- sumption that “Jack the Ripper” died or was put under restraint after the Miller's court affair, which ended this series crimes. It wouid be interesting to whether in this third case the man was left-handed or ambidextrous, both sug- gestions having been advanced by medical experts after viewing the victims. Cer- tain other doctors disagreed on this oint, which may be said to add another o the many instances in which medical evidence has been conflicting, not to say confusing. Yet the incontestable fact remains, un- satisfactory and disquieting, that many murder mysteries have baffled all in- quiry and that the long list of undiscov- ered crimes continually receives many mysterious additions. An erroneous im- pression, however, prevails that such fail- ures are more common in_Anglo-Saxon countries than elsewhere. No doubt our olice are greatly handicapped by the Yaw's limitations, which act always in protecting the accused. But with all their advantages and the power to make ar- rests on suspicion, to Interrogate the ac- cused parties and force on self-incrimina- tion, the police of Continental Europe meet with many rebuffs, Numbers of cases are ‘‘classed,” as it 1is officially called in Paris, put by, pigeonholed for- ever and a day, wanting sufficient proofs for, trial, in the utter absence, indeed, of any suspected person to try. In every country and at all times, past and present, thers have been crimes that defled de- tection. Secret Poisoning. It 18 generally held that secret poison- ing hds much diminished in these later days, and.no doubt the law, assisted by science, affords better protection to the general public nowadays. We are now closely safeguarded by the regulations that govern the sale of poisons; science has a de?er insight into the properties of lethal drugs and better aids detection by improved methods of analysis and a readler, more positive recognition of the traces and effects of poison. Again, the stringent and precise rules in force as to death certificates, the law that the cause of death must be in all cases attested by a properly qualified medical practitioner, is a great guarantee, a.mwush. as we shall see, its value may be diminished under new conditions of interment. A chief obstacle no 8oubt to a free, un- lawful use of poison is the difficulty of access to the person threatened. Now and again the reckless homicide, who kills for mere pleasure of it, casts his or her oisonous net over a whole circle, some amily, some gathering of people, by the casual’ distribution of polsoned food, cakes, confectionery and so forth, to taks effect as it may. But if thers is a definite, deliberate intention to murder a particu- lar victim, facility of access is a first indispensable condition, As a . naturai consequence the use of polson is very largely limited to particular agents, who enjoy special advantages of time and place, to women and doctors, in short, whose ways of life bring them into daily contact with those they have marked down. It will be found that this is al- most a general law. The most notorious oisoners of modern time have been mem- ers of the medical profession, chemists and females, whether wives, nurses, com- panions, cooks or servants, intimately as sociated with others by natural, family or domestic ties. American statistics show that some five-eighths of female homi- cides by poison in the United States were in personal service—housewives, house- keepers, servants, washerwomen and nurses. Does Science Aid the CriminalsP An uncomfortable feeling prevails that modern science is not altogether on tue side of defense. It may assist deteétion, vet it has multiplied the methods of pois- oning by many chemical and other dis- coveries. Some of the newer pro: fa- vor the criminal; many produets, animal, vegetable and mineral, are avallable which leave little or no trace if cau- tiously administered. Improved knowl- edge, again, has developed the practice of chronic or gradual polsoning, of &ap- ping life by small deleterious doses that eventually cause death, but only after simulating the symptoms of natural dis- ease. SIr Henry Thompson, in the spring of last year, when engaged In ‘a controversy as regards cremation and its possible ef- fects in encouraging - crime, strongly urged the appointment of a special expert medical officer to examine all bodies be- fore they are disposed of for cremation. He believed that in the future .“easily decomposed compounds are likely to be used, the existence of which it is difficult if not impossible to verify after two or three days.” Can it be that the present infrequency of criminal poisoning, as evinced by the daily records, is due to the employment of these safer lethal substances to which Sir Henry Thompson refers? An uncomfortable feeling has been aroused by the out- spoken evidence of another eminent med- ical man. Sir J. Crichton Brown at a public lecture stated explicitly there were organic poisons well known to experts which could be used with impunity with- out the slightest fear of detection. “A connofsseur_ in poisons could, by keeping microbes,” he explained, “slaughter hun. dreds of innocent persons without the slightest fear of his crime coming to light.” He, however, qualified this sweeping assertion by stating his belief that these poisons, In his wide experience, were rarely, if ever, illegitimately used. e The stories about Frenchmen eating snails are believed by many people to have no foundation in fact, but snails are eaten and to a very considerable extent in France. Nearly 100,000 pounds’ weight of snalls is sold daily in the Paris market, to be eaten by dwellers in that city. They are carefully reared for the purpose in extensive snail gar- dens in the provinces and fed on aro- matic herbs to give them a fine flavor. One such garden in Dijon is said to bring in to its proprietor several thou- sand francs a year. Many Swiss cantons contaln large snail gardens, where they are reared with great pains. They are not only regarded as a great delicacy, but are considered very nutritious. Hygienists state that they contain 17 per cent of nitrogenous matter and that they are equal to oysters in nutritive properties. Snalls are also extensively used as an article of food in Austria, Spain, Italy and Egypt and the countries on the African side of the Mediterranean. Indeed the habit of eating snails as food has existed in various parts of Europe for many centuries.