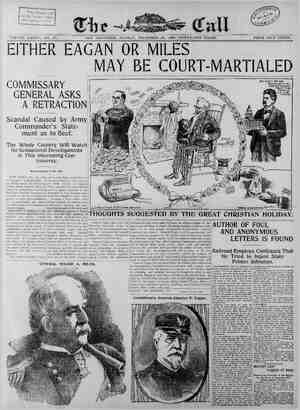

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, December 25, 1898, Page 19

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN FRANC CO CALIL, SUNDAY, DECEMBER 25, 1898. 19 OUR CHRISTMAS AMID THE TERRORS OF DEATH VALLEY. For the First Time Since 1850 Mrs. Julia Brier, the Only Woman of the Party, Re- lates the Awful Experiences of the Trip. MR, 0404040 the edge Rev. J. home Lodi his wife f the town of W. Jr, Mrs. and two sturdy lives Julia her son, Brier modest, wee old lady, now in her eighty-fourth nous Death Valley party. This is the first since 1850 that she has spoken of that awful experience to a news- paper representative. ‘n( sine of the @040+ 04040404C Kirk gave out a nd I carried him on my back, barely seelng where 1 was go- >w how to tell you about ing, until he would s fother, I can ggle through Death Valley Walk_ now Poor little fellow! He the Christmas we Would stumble on a little way over the horre I never ex. Salty marsh and sink down, crying, “I can’t go any farther.” T about it for WALKED ACROSS DEA-rn VALLEY 404 0404040404040 40404040404 04040409040+0+@ 404 04040404040 40404040404040404040 4040 40+04+04040+ 6RIER THE WOMAN \WHO 49, .- n WJJ:'T{Tl"‘“"' 0404040404040+ carry him again, and soothe him as Iw only wo- best I could. arty—Mr. Brier, our three Many times I felt I should faint, and s, and Kirk, the as my strength departed I would sink ing nine yes: two young ©n my knees. The boys would ask for John and Patrick, made up Water, but there was not a drop, Thus s laie we staggered on over salty wastes " s ir to keep the con w and d the top of the ide be- hoping at every step to come to the t Death and Ash valleys and, oh, springs. Oh, such a day! If we had Death what a desolate countr e looked Stopped I knew the men would come ea into. |The next.morning we DACK S night for us, but T didn't want: “No; iv miles farther,” he said. 1 nen said they could “‘\.’*h‘h‘)j’&“‘ a drag or hindrance. 1 was ready to drop and Kirk was i it in the ¢py }Etf‘fl;;“, down and we lost all almost unconscious, moaning for a always ahead oLack of those @head. I would get drink. Mr. Brier took him on his back y. 3 ; : y @ ahead down on my knees and look in the star-' and hastened to camp t ave his little to explore and find , 50 1 was left light for the ox tracks and then we life. It was 3 o’clock Christmas morn- with our three bo » help bring up Wwould stumble on. There was not a ing when we reached the springs. I the cz We e: 1 to reach the Sound ZA{\d I didn't know whether we only wanted to sleep, but my husband gs in a few 1d the T “"\J“"Ju“"‘;r“:,~l‘;'t;’x!u"fln1x‘ or not. 5 said I must eat and drink or I would ahead. I was sick ar- sbouts we came around a never wake up. Oh, such a horrible 1 .r):" i T ] 2 4‘?(“‘}“1:"“]{": s big ,g\ and there was my husband at day and night! ; ope of a good camping pl a small fir We f ings the kept me up. Poor little Is this camp?” T asked. R B > OO 0O 0 @ ® R and washed and scrubbed and rested. LR R R SRR R R R R R OB RO L ORI R OR Y That was a Christmas none could ever forget. Music or singing? My, no. We were too far gone for that. Nobody spoke very much, but I know we were all thinking of home back East and all the cheer and good things there. Men would sit looking into the fire or stand ~azing away silently over the moun- tains, and it was easy to read thelr thoughts. Poor fellows! Having no other women there, I felt lonesome at times, but I was glad, too, that no other there to suffer. The men killed an ox and we had a Christmas dinner of fresh meat, black coffee and a very little bread. I had one small biscuit. You see, we were on short rations then and didn't know how long we would have to make pro- visions last. We didn't know we wers in Californ Nobody knew what un- told misery the morrow might bring, so r >casion for cheer. r’ d to me that night: “Don’t you think you and the children had bette xcmdln here and let us send back for u? P 5 kxw\\ what was in his mind. “No,” I said, “I have never been a hindrance, I have never kept the company wait- ing, neither have my children, and ever ep I take will be toward Cali- fornia Then I was troubled no more. As the men gathered around the blazing camp- fire they asked Mr. Brier to speak to them—to remind them of home—though they were thinking of home fast enough anyway. So he made them a speech. It was a solemn gathering in a strange r/' ‘/,/A/ i S The Brier Family Struggling Across the Arid Wastes of Valley. place. So ended. I believe, the first Christ- mas ever celebrated in Death Valley. The next morning the company moved on over the sand to—nobody knew where. One of the men ahead called out suddenly, “Wolf! Wolf!"” and raised his rifle to shoot. “My God, it's 2 man!” his companion cried. As the company came up we found the thing to be an aged Indian lying on his back and buried in the sand—save his head. He was blind, O@@@@@Q@@@@. ® UGCGSS 01‘1 C : & 4 TR Y PPPPIPPIOVIPPPPPOPOPOOOGSPDOS® @fl@@@ve@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@9@@09«)@®©®O®®@6®©®®®0000 RE is only one way to learn | hands all through the scene. And of | Annapolis. Our family was not very [about it. Worse yet, th2y said I to act, said Stuart Robson, | course, 1 had been doing flumuhmg prosperous when we removed to Balti- | couldn’t play in their company any that is to go on the stage ‘u.:th them. Now, it is not so es s | more, and my mother opened a gen- | more, for they weren't goinz to be ight think to your ha that before do nothing w In all the history cf the staze the two great expon- art-whose success 4 u\hm way. They and ac I could compass it. went up to its fin.1 fall. getting on before that night. knew it. that they were path of ordi- at to go on the sta the advice from me I should say get a place not ged to \.u.‘li , and it was some time afte One night I realized that I had not thought | of them from the time the curtain first I hoped I was Then I| If you were a young man, determined | and anxious to get to your best course, in a company | h eral boarding house, which in time | came to be a theatrical boarding house. “AII boys, as you know, are fand of the theater, and the fact that actors ate | at my mother’'s table, where they were | | | natural infatuation for the stage. the time I was 12 I was fully deter- mined to be an actor, and nothing could | change my mind. One of my closest | companions was a boy named Theo- | dore Hamilton, 2 member of my com- | ) inderstand I have|and begin. It would not matter how | pany this season, by the way, and one 1ted ons who gnificant the role, so long as you|day, as we were talking in the streat o act acceptably after i‘)\':‘}“""dmn‘_viurrn-( (10'1 Z0 “x”i it .\'nxu- together, he pointed out a tall, awk- ¢ Balio _ | had Yyou to act it would come oul. | ward boy on the opposite side of th in the/echacle but whato|No, I wouldn't “advise a preliminary | wa y ieaR SR a ned of true success | course in any of HF e schoo! b 3 * red of true st | course in any of the dramatic school That boy’s father.” ‘said’ Theodora, of their teaching in led, for on the stage you would | “is a very big actor. Hig narme 14 cause of it. Act- e to unlearn most of what you had ¢ 2 £ t be m most other profes- of law, theology be learned in | - of these princi- | with those who | been taught. ing ycung actors and actresses how forget what they have been taught the schools. 7 After you had got your rlmnce tread the boards, I should say pay sions. d the hool & s is the m become 1 divines, teachers, | attention to the instructions chemists a e. You may, after | stage manager. The success of each | a7 dasnl hat are termed the | production depends on the conduct principles dramat art, but their | | stage manager’s bu | all appear to the best advantage pos application can irned before the | footlights only. ble, both individually and as a I was led to comprehend this truth | pany. yeéaraiago, when only a man. I| Next to the stage manager, voung was playing with Be 3ar, after Mr. Burton, one Of the most capable com- edians of modern times. I had reason to that T w etting o et 1 was tion. each other, and I have yet to learn hope 5 g with De I m-.u;,m I would get | We are constantly show- | som- | Edwin's brother, actor will find older members of the profession the best sources of instruc- | 0f pleces manufactured expressly for Actors generally delight to help | 0uT own company by its older mem- from satis yself. So, one | would not go out of his way to give zht, after a which I had n on t some minutes | telligence and ambition. In a way I must say that my earliest | nius Brutus Booth, and the boy's aame | is Edwin.” I remember that I looked at that boy with awe and wished he were a friend of mine, but you know how it is with | boys of 15 and boys of 12. He was a to in ln S Clone | big boy, and we were little boys, There was a great gulf between us. that Later Edwin Booth, my older ot | heard each and all the actors, and it is the | brother, and a few other big boys wcre iness to see that | 8€tting up a little dramatic compan: | Still later they said we small boy: John Wilkes - Booth | being among the number—might ome. ‘]‘c.\mm"‘[imeh take part, and we actually did 80 a few times, the performances being of | bers.” Our admission prices rangel a player of experience and ability who | ffom 1 cent for a boy to 3 cents for i { Irish washerwoman, and we ased . | points to an inexperienced actor of xmildk? in enough money to buy candm for the footlights. however, My own appear- ances, were few, since my some instru I told him T was not | instructions were received from Edwin | mother objected to so small a boy as ple d with my bearing in that scene; | Booth, continued Mr. Robson, but they | I appearing on a stage, even in nlay, that 1 was especially “disturbed ,muuq“p.p not very elaborate, since we |and one night she climbed to the lof: 1 managed my hands. g t worry over your hands, Robson,” he “Forget them.” You see I had been thinking of my 'in Baltimore, though I was born Mr. | given. | were both youngsters when they wers Most of my boyhood days were spent where our show was going on and tcox me away by force. That almost broke my heart and in ! the older boys jeered me unmercifully mstantly talking shop, added to my | By | bothered with boys not old enough to be untied from their mother’s apron strings. But they did consent to let it in the audience, deadhead, and vas a regular attendant. One night had a big house. There were sev- pay boys, another deadhead be- eral sides myself, and at least four wash- erwomen present. Just as the curtain went up an unusual thing occurred. A man paid his way in and came climb- ing up the ladder. He was all mufflcd up in an attempt to hide nis face, but 1 noticed that his eyes were piercing and that he had a broken nose. The boys before the footlights paid little or no attention to him at first, but the time came when he held the center cof the stage. Edwin had just come on and was rolling off his lines at a great rate, when the muffled-up man sudden- ly exposed his face, with ihe piercing eyes and the broken nose, and, stridiLg from auditorium to stage—both being on the same level—seized the boy hy the ear, cuffed him soundly and hauled him struggling down the ladder. It was the elder Booth who had broken up the performance. He was of one | mind with my mother as to the pro- priety of boys playing at theatricals. Edwin was then sent peremptorily to the family farm at Bel Air, Md., and I never saw him again till after he had become famous, and I had myself been a professional actor for years. ‘When I met him T asked him if he re- membered how his father had yanked him out of that loft. He did perfectly, and we had a good, hearty laugh over the remembrance. * —_———— “Do _yez b'lave in frinology?” asked Mr. Dolan; “meanin’ be that the sighnee of tellin’ a man’s charackter be the lumps an’ 'is head?” “Iv coorse,” answered Mr. Rafferty; “there’s nothin’ gives a better clew 'to a man’'s habits than lumps, black eyes, patches iv shtickin' plaster, and the rest iv such signs."—Washington Star. shriveled and bald and looked like a mummy. He must have been one hun- dred and fifty years old. The men dug him out and gave him w dlux and food. The poor fellow bless pickaninnies!” Wherever he had learned that. His tribe must have fled ahead of us and as he couldn’t travel he was left to die. When we reached the Jayhawkers’ camp they were about to burn their wagons and pack their oxen to hurry along. That made us still gloomier, b none complained. The men that ‘to stop or go back meant death, and they determined to ruggle on while strength and life lasted, trust- ing to-morrow to bring them to the land of plenty. Then we . struggled through the salty marsh for miles and miles. Oh, it was terrible. We would sink to our shoetops and as water gav: out we were nearly famished. I have heard since that Governor Blaisdell of Nevada found our tracks there ‘twelve years later and still encrusted in the hardened salt. A march over twenty miles of dry sand brought us to the mountains, with hope almost gone and not a drop of ater to relieve our parched lips and swollen tongues. The men climbed up to the snow and brought down all they could carry, frozen hard. Mr. Brier filled an old shirt and brought it to us. Some ate it white and hard and relished it though it was flowing water, enough was melted for our frenzied cat- tle and camp use. Here we lived reali on jerked beef and miserable pancak Some of the com- pany told us they were going to leave their cattle, bake up their provisions and push ahead as a last resort. Dr. Carr broke down and cried when we would not go back to the springs. I felt as bad as any of them, but it would never do to give up there. Give up— ah, I knew what that meant—a shallow grave in the sand. We went over the pass through the snow into what they named Panamint Valley, and found a deserted Indian vil- lage among the mesquite tree: We were rejoiced by seeing hair ropes and bridles and horse bone: had reached civilizati The men ahead, however, could nnl} report more sand and hills. After two days here we struggled away into the desert, car- rying all the water possible. We grew more fearful of our provisions and watched each mouthful, not daring to make a full meal. Coffee and salt we had in pienty. The salt we picked up in great lumps in the sand before com- ing over the last mountains. Our cof- fee was a wonderful help and had that given out I know we should have died. New Year's day was hardly noticed. We spent it resting at the head of Panamint Valley. Sometimes we went south and again north, not knowing whether or not we should get out of that death hole of sand and salt. On January 6 two of our mess decided to leave us and take their provisions. These men—Masterson dand Crump- ton—owned the only flour we had, so they baked up their dough, except a small piece, which I made into twenty- two little crackers and put away for an emergeney. Then with tearful eves they gave us their hands, with averted faces, and turned away without a word. That was our last bite of bread until we reached San Francisquito Ranch, six. weeks. later. From that on my husband and I and the poor children and St. John and Patrick lived on coffee and jerked beef, except when we killed an ox for a new supply. Even then there was not an ounce of fat in one and the marrow in their bones had turned to blood and water. Did I blame the men for leaving us as they did? Oh, it happened so long ago 1 can hardly tell now—and thev felt that they ought to try to save their own lives. The valley ended in a canyon with great walls rising up—oh, as high as we foot of the: could see, almost. Wi out, for it ended almost in £ ght wall. I know many of the company never expected to leave that narrow gorge. By that time most of them could hardly stagger more than a few eps at a stretch; some were beyond even that. Mr. Brier managed to keep erect with the aid of two sticks. Providence was with us that awful night, or the morning would have risen on the dead. Seeping up from the sand Mr. Brier found a little water, and by digging the company managed to scoop up about a pint an hour. Coffee and dried beef kept us alive till morning, but the moaning’ of the suffering cattle was pitiful. At daylight we managed to reach the lowest bench of the cliff by holding to the cattle. ‘Father Fish came up by holding to an ox’s tail. but There seemed no could go no farther. That night he died. I made coffee for him, but he was all worn out. Isham died that night, too. It was always the same—hunger and thirst and an awful silence, so I'll just tell of one or two more experiences. Everybody knows how the company went across:the Mojave Desert and fin- ally reached ‘San Francisquito ' Ranch. Our greatest suffering for water was near Borax Lake. We were for forty- eight hours without a drop. A mirage fooled us. "We went to bed hoping against hope. In the morning the men - returned with the same story: “No water.” Even the stoutest'heart . sank then. for nothing but sagebrush and dagger trees greeted the eye.* There: were wails and lamentations from lips that had never murmured before. ~ My hus- band tied little Kirk- to his back -and staggered ahead.. The child “would ur occasionally, “Oh, father, the water?”; His pitiful, deliri- ous wails were \\Ur?. to hear than the killing thirst. = It was terrible. I seem to see it ‘all over again. 1 staggered and struggled wearily behind with our other two boys and the oxen. . The lit- tle fellows bore up bravely and.hardly complained, though they could barely talk, so dry and swollen were their lins and tongue. John would try to cheer up his brother Kirk by telling him of the wonderful water we would find and all the good things we could get to eat. Every step 1 expected to sink down and die. I could hardly see. At last we came upon two Germans of the company, who had gone. ahead. They were cooking at a tiny fire. Any wate asked my husband. here's vasser,” one said, pointing to a muddy puddle. The cattle rushed into it, churning up the mud, but we scooped it up and greedily gulped it down our burning, swollen throats.' Then I boiled coffee and found the pot half full of mud, s0 you can see what that water was like. It ¥ wful stuff, but it saved cur lives. A little later we came to a beautiful cold spring. Oh, how good it was. I have always belleved Provi- dence placed it there to save us, for it was in such an unlikely place. Sometimes we found water and grass in plenty, but never a thing to eat, save where we tried making acorn bread, and that was a failure. And the silence of it all!, At night I would go to bed praying ~for God to help us through. “Oh.” I thought, “if I could only see something to show the end of our journey.” But I didn’'t dare speak of it for fear of alarming the childre: But I never lost hope. I couldn’t gi up. We needed all our hope and faith. I knew before starting we would have to suffer, but my husband wanted to go, and he needed me. When near the place where Mojave is now Robinson said to me: “Mrs. Brier, I have a presentiment I shall never reach California.” None of us knew then that we were well across a section of the State. “Oh, yes, you will; don’t give up,” I \\ ‘fi \ k\ ‘r); said to cheer fell off his pon: a shallow grave laid him to res Father Fish said he thought the Lord would bring him through because he came in such a good cause. He in- tended to raise enough momney to pay off his church’s debt, back in Northern him. The next day he and died. The men dug with their knives and Indiana. Then there was Gould. He would pick up aveérything the rest threw away, until he bad so much that Mr. 3rier gave him an ox to carry his load. Gould repented and had a most happy n out in the desert. - bread gave out one man, in_our party com- ort allowance of bread. I told him we must save it as long as possible, and he said, with an oath, that he would have it while it lasted. “You shall,” I said, “but that won't be long,” and it wasn’t. Then he left our me Before we were through that journey I he: for even the ent: Did I nurse the s little of that to do. I could for the poor fellows, but that wasn’'t much. When one grew sick he just lay down, weary like, and his life went out. It was nature giving up. Poor souls! So'we went on and on until the morn- ing we arrived at San Francisquito ranch. Oh, that was a beautiful morn- ing. Just ' before this the men had killed a wild mare and two coits and the:company: ate the meat with a relish, but it tasted-too' sweet.- This morning, February- 12, 1850, the sun was bright and .the grass and flowers seemed like paradise after the awful sand and rocks of the desert. One of the men shot a hawk and another a rabbit and we were preparing to ‘have a feast on them, when we heard more shooting ahead. The: wind blew toward us the sound of lowing cattle and.-we were. in great wonder. The Jayhawkers came rush- ing back with dilated eyes, saying they had. seen ten thousand:head of cattle and \\agon tracks and believed we were near a farm." Oh, what an excitement came over -us! Soon we came up to where the Jayhawkers had killed some cattle and saw thousands of head all around, and the men eagerly cut off pieces of the warm, raw meat, ready to devour it, when an old Spaniard and some Indian vaqueros came galloping up on fine horse: Our men expected trouble and held their guns ready The Spaniard was amazed at our appearance, I suppose. ‘We looked more like skeletons than hu- man beings. Our clothes hung im tatters. My dress was in ribbons, and my shoes, hard, baked, broken pieces of leather. Some of the company still had the remains of worn-out shoes with their feet stickine through, and some wore pieces of ox hide tied about their feet. My boys wore oxhide moccasins. Patrick knew a little Spanish and said to the Spaniard, pointing to Mr. Brier, “Padre.” The old man took off his hat, bowed and said in a broken voice, “Poor little Padre!” He led us up to his house and the old lady there burst out crying when she saw our condition. They were very kind and cooked us a grand feast, killing the finest animal among their cattle in honor of the “padre.” Our stomachs were too weak to di- gest the solid food and we nearly died in fearful agony after eating so heartily. In the midst of our awful pain Dr. Irving of Los Angeles happened along and by the use of medicines relievea us. But for him some would have died, for the men were rolling in fearful pain, all bloated, on the ground. We rested at the ranch and then traveled on to Los Angeles without trouble, being aid- ed all the way. It was like coming back from death into life again. It was a long, long, weary walk, but thank God, he brought us out of it all. ard that man begging of a crow. Ah, there was I always did what i"’ il \\‘" (i} il m‘ Al "t‘\\“ Rewe .«\\\\“““ s K " \\\i ““Is -this 'camb?" I gasped, as | staggered into the firelight.