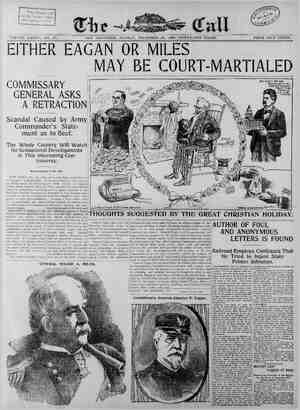

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, December 25, 1898, Page 18

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

18 THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL. SUNDAY, DECEMBER 25, 189s. % HALL CAINC CRITICIZES AND COMMENDS OUR STAGL. <% POPOP0O0PCO0000000000000000000600 MR. BRONSON HOWARD'S lish dramatist. were sent by The Call our actors and managers, a ard’s brief yet comprehensive reply: are concerned. P00 0006060606066606 0 yours, To the Editor of the Call: HAVE now spent six months in America, three months on a former visit and three months on the pres- ent visit. Half a year's acquaint- ance with a vast country does not entitle me to sit in judgment upon it, but since you ask only for impressions I am willing enough to give mine as simply as possible, without any pre- tensions to finality of judgment, and, of course, without any disposition to meke points at the expense of truth, Let me speak first of the things which come closest. I came to America to pro- duce a play, and hence the theater has covered a large part of my horizon. Your American theater differs from our English theater at more points than one. Your buildings are better for see- ing and hearing, but not always so gooa for ingress and egress, and they would, I fear, in some instances, be less able to cope with the dangers of fire or panic. In general comfort your houses are superior to ours, and incomparably better than almost anything in Paris or Berlin or Rome. Your prices of ad- mission vary less than with us or with the French, but the gross receipts of your houses, compared with those of any other houses I know of, capacity for capacity, are materially higher. Theatrical Management Good. The management of your theaters Wwould seem to me on the whole excel- lent. Even that tyrannical innovation, the Wednesday matince, has something to say for itself, the theater-going pub- lic in your outlying districts being so great and consisting so ]argel‘v of ladies. The Wednesday matinee of a new play in New York is probably the surest and swiftest test of success. If it §s good, if it grows, if it displays in- terest, if it shows sympathy, your man- agement may be content. They have then got the nucleus of the best public they can play to. Your audiences differ from ours in more points than one. It is often said in England that they are less demon- strative than our audiences. That is both true and not true. I have more than once seen the curtain fall in New York on an acceptable play, with no applause whatever, and in Boston the restraint of the audience has some- times seemed to me almost as marxed and painful. But, on the other hand. I have never even on a first Light at & popular theater in London * heard applause more sincere and prolonged than in Boston and New York. ‘° As a general view I should say there is less complimentary applause with you than with us, but I would even recommend to. your audiences the adoption of a little of that dubjous form of appreciation as a means of getting the best out of your actors. Our stage folks all the world over are grown up children. God bless them. and there is nothing which® inspires and cheers them more than “the clap- ping of hands in a theater,” Your American audiences have little or none Mr. Hall Caine’'s comments upon our stage, being those of a leading Eng- to American playwright, with the request that he read the English author's let- ter, and, if English and American views differed, that he would, on behalf of wer Mr. Caine's To the Editor of The Sunday Call : I have read Hall Caine’s letter, and cannot write a thing about it, simply because | agree with him from beginning to end, so far as all important matters treated He seems to be keenly observant, with perfectly balanced judgment, from beginning to end. Except merely to enlarge on what he says, I could merely sign my own name under his, Sincerely BRONSON HOWARD. 0002000900000 0099000000000900000999 ® @® ® @ ® - CRITICISM OF MR. CAINE Mr. Bronson Howard, a leading argument. This is Mr. How- P ZORCRCRCORORORCRORORRR R RCR X AR S S A d HALL GAINE, the English Novalist. From a Photograph Taken Just Beore He Sailed for Home, of that languor of dramatic satiety which 7~ use our own phrase) is “the most difficult propesition” the English dramatists and actors have to count with. Not long before leaving London I sat at a new play in a well- known theater behind two fashionable ladies and a fashionable man. At in- tervals during the performance they talked of their own affairs, and once between the acts the man said: "“Am— er—sorry I—er—brought you to this—er —play.” “Oh, don’t mention it; I'm not at all bored,” replied one of the ladies. American Theater-Goer Loves a Lover. Nothing of that kind is ever to be found in an American theater. Your leisure class is not large enough to bring the atmosphere of ennui into the playhouse. Your people go into the theater to be amused, not to kill time or to break up the weariness of idle lives. They are like children in the simplicity of their emotions, and, like children, they are not afraid to be made to feel. They do not run away from strong passions, and when they are appealed to they respond. Naturally they love to laugh, but’if they can cry and laugh together they like that best of all. The prevailing taste of your Ameri- can audiences it is easy to indicate. Nearly every kind of dramatic fare is acceptable to them, but what they love to feed on Is love. The manager who would produce a modern version of “Julius Caesar” would be a daring man indeed, but the crudest adaptation of “Manon Lescaut” would have its chance in America. Sensation, street life, character in its quainter forms, all these hold their places on the menu of your American public, but always the dish of the day is love. The man- ager who sees that sees well. He brings to his doors a charming and responsive . section of your public which is perfect- 1y certain to bring all the rest. American Actors Hold Their Own. Your foremost actors and actresses, with some exceptions, may be said to belong equally to 'England and to America, and therefore it would ill be. come me to say more about them than that we reckon them in the number of our best. And among those who are still unknown to our people there are a few who are sure to come into the heri- tage of their English fame when time and opportunity allow. But not to walk, however warily, on such dellcate ground, I could wish to say, after somewhat intimate experi- ence of at least two American.compan- les, that the rank and file of the Amer- jcan dramatic profession seem to me at all points equal to the rank and file of the dramatic profession in England. I notice points of difference. You have not so many imitators of great actors. A few vears ago every English com- pany contained two or more imitators of Henry Irving, and there are still but few traveling combinations without their colorable version of Ellen Terry. I do not recognize your Jefferson in embrvo, and if there was ever a line of Booths 1 fear the school (with the exception of two or three of your act- ors) has unhappily died out. English Scarcity of Stage Lovers. . I think T observe that your dramatic talent has in one respect adapted itself to a certain dramatic need. You have, perhaps, more young actors equipped by nature and the training to the role of stage lover than we have had on the English stage for years. Since the days of Harry Montague our young men have been obviously a little ashamed of playing the lover, and certainly no- body with us has deliberately set out to win the prizes of that character, with no other pretensions and nothing else to him. The recent revival of the romantic in English drama suggests the bility that the English stage may yet require to make drafts upon the American stage for the stage lover, in which case the scarcity of the type on both sides of the water will probably raise the reputation and emoluments to be gained by it to that of the fash- fonable poet in France and the foreign Ambassador in England, and settle for good the vexed question of “what to do with our boys.” Your American stage knows less than our English stage of that modern au- thority, the actor-manager, and so far, if I may say it without offense to friends and comrades, its state would seem to me the more gracious. Though I see that the actor-manager. has done excellent work for the English stage during the last ten or twenty years, I also see that he may have prevented other good work from being done, and I feel the constantly narrowing range of his possibilities. The most beautiful and attractive thing on the stage is youth, and while the actor-manager can remain young he can be in the heart of all the inter- ests whereof youth is.the rallying point; but as the years creep on him and he struggles to shift the focal cen- ter of fascination and charm—he must needs do so or let another push him from his place—he is playing a fast and loose game with public attention and sympathy and is likely to be stranded before he knows it. Impending Tragedy in an Actor’'s Life. This is a tragedy which has befallen more than one actor-manager in the past; it is happening to some of the actor-managers at this moment and will happen to others as time goes on. The life of an actor is a short life, the life of an actress is still shorter. That is the essential cruelty in the career of the stage. But there is one way to meet it—that of adapting yourself to the conditions as they change. One of the first of American actors has done this with great wisdom, but the theory of the actor-manager is to resist that necessity. He is fighting a law of nature and must, therefore, always in th2 end succumb. . The story which the stage tells year in and year out is the story cf youth, yet actors cannot always be young, and for the purpoSe of the drama (speaking broadly and generally) an old man's story is no good to anybody. The * Star” System. But if you have léss of the rctor- manager system than we have in Iing- .land you have more of the “star’ sys- tem, and I am by no means sure that the operation of the two is totally dif- ferent. Let me say at\once that I see much in your condition which explains if it does not entirely justify the star system. The public interest so gathers about an artist as to force him into the pu- sition of prominence. He is a favorite, and is usually nothing loath to be a center of sympathy in himself. But this “splendid isolation” is a position beset with dangers, with trials and with anxieties. I do not speak of the THE GREAT ENGLISH NOVELIST COMMENTS ON THE AMERICAN STAR SYSTEM AND SHOWS HOW IT CONFLICTS WITH : HIS IDEA OF THE DRAMA. Written Specially for The Call-Herald the Day Before He Sailed for Home. Jealousies it provokes, for these, how- ever vexatious, are often both natural and salutary as a spur and an inspira- tion. I would rather point to the es- sentially non-dramatic principle of tha star system. It conflicts with the idea of the drama. If a play were like a novel of Fielding, an organism center- ing in a single individual, the star sys- tem would have much to say for itseif, even on grounds of art. Occasionally a play does center in one character, as in the case of “King Lear,” but there the method of Shakespeare is the method of Homer, the method of Field- ing, the epic method, and glorious as “Lear” is as an epic poem it is poor as a stage play, and not even the greatest herofc actor can make it hold the stags. Now, the theory of the star system belongs to epic art, and any general attempt to make dramatic art accom- modate itself to the necessities of th star system would be to break dow the one without establishing the other. Dang:rs to the American Stage. Drama lives by the clash of incidents, emotions and impulses, and _its best work can only be done where all its forces are at full play, at white heat and at utmost strength. Any effort to secure the result without the means must surely fail. A good Romeo and a bad Juliet make a poor performance, and the system that tempts us to the danger of such a combination is folly. It would seem to me, however, that the worst risk your stage runs is not that of an inadequate support. It is the risk of the drama itself being made to take shape from the necessities of the star system. To make the dramatist play second to the star, however popu- lar and attractive, would be a cardinal error. Any attempt to do so would re- solve itself inbo a trial of strength be- tween actor and author—which has the greater appeal for the public—and there could be no question of the reply. The play is the thing, and always has been, and the most gifted actor cannot draw independently of subject. I remember ‘Wilkie Collins telling me that Fechter had said in his heydey that he could draw the town six weeks in an unpopu- lar play. Is there any English or American actor of whom even as much as that could be said now? Speaking for myself, I have no griev- ance against the star system, and the only star I have been imniediately con- cerned with during my visit to America has borne her trying position with the utmost artistic unselfishness and charm, but I will risk all misunder- ‘standing and say at once that your American star system as a whole is not good for the production of good plays. I will even risk all small witticisms and say that if you must have the star sys- tem, the best thing that can happen for the American drama is that you should “star” the American dramatist. That is a condition that is coming in any case. I think I see a time not far in the fu- ture when the dramatist will be the master of the theater, just as he was in the best days of the drama, both in England and in France. The dramatist will be the rallying point of public interest, as actors and actresses now are. When he has once established his right to be heard he will be engaged by business men for terms of years to write plays for a particular theater and the theater itself will be called by his name. The extraordinary disproportion of his present position will in the near fu- ture be altered by a violent change, and when the dramatist has come into his own again the drama will live and grow. i Here's a Question for Actors. It can hardly be hurtful, even for an English dramatist, to say that the American stage seems to be strangely dependent on the contemporary French and English drama. Traveling through your country I was constantly im- pressed by this fact. Nearly all your country playbills bore the names of French and English plays and play- wrights, and the picture posters every- where depicted French and English scenes. Naturally, I can have nothing but warm feelings toward the liberality Mr. Hall’ Caine has long held a prominent position in the world of les ters as a novelist who is a close observer of men and women of the day and with a keen insight into the strength and weakness of their character. Later he became noted as a playwright possessed of dramatic ability of a high order. Probably none of his books has created so wide an interest and pro- voked so much comment as “The Christian,” spring, stands head and shoulders above ‘hi which, among his literary off- Placed upon s other creations. the stage, it has become one of the dramatic sensations of the season. Mr. Caine througl this play has assumed a leading position among con- temporary dramatists of the English stage. For the past three months he has been here attending the production of “The Christian” and in his leisure moments observing and studying the American stage and At the request of The Call-Herald he here gives the result of his diences, American au- observations, contrasting the theaters and theatrical influences of London and New York. 00000000000000000 Q000000000000 00 which enables you to accept English dramatists with as much brotherly good will as if they had been born and bred among yourselves, but I am none the less amazed that a country so full of romance, of wonder, of surprise, of scenic splendors, of varying and con- flicting races, of many tongues and many dialects, of extreme wealth and extreme poverty, should lack for dramatists to present this vast mine of dramatic wealth upon the stage. Some representative plays 1 know you have, and no one admires these few preducts of your dramatic genius more than I do. But the day is surely coming when this teeming and impetu- ous life of your tremendous country will be enough for you, and you will come to us (as we will come to you) only for those plays which are beyond and above all limitations of race and time and place. One of the first signs of the coming of the good time will be an altered and elevated estimate of the theater as a force in modern life. The American attitude toward the theater differs from the English attitude in being at once more generous on the moral side and less respecting on the intellectual side. . You do not rail at your stage folk or regard them as outcasts or cling to the traditional slanders which the old English word ‘“vagabond” appears to imply. It may be that your dramatic profes- sion are a class more circumspect than ours in their walk of life, but I am con- scious of no such reservation of moral approval with respect to them as even the most liberal of our typical English people display toward all but the best of your actors and actresses. But on the other hand you do not count with your dramatists and actors quite so seriously, whether as public men and women or as artists. The Theater as a School of Morals. The theater is your place of amuse- ment, and in no other light do you re- gard it. As a temple of art it takes a secondary place. As a school of morals it has no place at all. It looms large in your daily pleasures, and there is probably no citv in the world where the theater is so flourishing as in New York. But it is only your show place, after all, and you regard the people who run it as ~our “show people.” I doubt if this is quite a hopeful con- dition for the birth of the great Ameri- can drama which is to come. If you want the best brain and the best blood on your stage you must begin by al- lowing them to have something to do with the serious affairs of life. Carlyle described a ballet girl as a “pair of scissors stretched.” You cannot expect the man of any mettle to settle down to the idea that under any circumstances he is expected to make a living by mak- ing a fool of himself. Theatrical Critics in General, Another sign of the good time com- ing for the American drama will be a more serious attitude of your dramatic press. Your newspapers give enough attention to the drama, and much of it is simple and 'dignified and of good effect. But much of it is also grotesque and fantasgic, unreliabie, insincere, un- duly persofj@l and even vulgar. As to its personnel I don’t know that there is much to choose between that of the dramatic press in New York and of the same class in London. Here, as in England, there is the entirely honest man who sets down in simplicity what he knows and feels, the ponderous egotist who is superior to everything and everybody, and the eynical young scribe who sits in judgment on other men’s plays with a play of his own in his breeches pocket. And here, as in England, the public makes up its mind for itself quite independently of 1> professed guides to critical opinion, whether good, bad or indifferent. Critics Don’t Make or Break a Play. One point of superiority you have in this regard over our people in England —our playgoers are prone to belleve whatever they see in the newspapers, and it requires an effort on their part to eonquer the effects of an unfavor- able impression made by the press. Your American people appear to have no such difficulty, and within a week of the general onslaught in the ne papers a play or a book in America may stand absolutely “‘as its own” and be in the full tide of its success. That is fortunate for all writers, and par- ticularly fortunate for some of them, the ultimate court of appeal being al- ways so just and even so generous. American Audlences. During my visit to America I have seen many plays in many theaters, and I cannot remember a single American audience whose heart did not ring true. That is not a common experience of the iraveler in many lands. 1t seems to be the accepted theory in America (only too well founded in fact, I am afraid) that the English visitor to the United States who has received honor and kindness here will make his bow on this side of the ocean and re- ‘serve his grimaces until he reaches the . other side. Perhaps in the sequél it will be found that I have reversed this order of things, for whatever ungra- cious criticism I may have had to make of that part of American life which has come closest to my experience is now made, and nothing,remains to me to remember but the generous apprecia- tion and cordial sympathy which my own little section of your great nation has given me from first to last. ‘‘Shake,” Says the Car Condugtor. Some freedom of handling I may have been conscious of at certain moments —perhaps some misunderstanding, and some personal misjudging, but nothing that has left any sore place in my mind, and grudge, any_ungenerous feel- ing, and for the rest I shall rethember my greeting on my second visit to America much as I remember the salu- tation of the conductor of one of your electric cars on Broadway. He was a boy of 20, with clear, bright eyes and a laughing mouth, and as I got on the car he looked me over from head to foot. “Will this car take me- to Fifty-sixth street?” I said. He didn’t reply to my question, but asked me another instead. ~ “Are you Hall Caine?” he said. “Yes—will it?” I asked. Again he did not reply, but holding out a grimy hand, he said, “‘Shake!” HALL CAINE. 00C0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 A Christmas Lynehing, lowa Hill, 54 HE night of December 22, 1854, witnessed scenes of mirth and tragedy in Towa Hill. The Queen City Hotel, the most imposing building in that prosperous min- ing town, was opened by its pro- prietor, John Roberts, with a grand ball, given under the auspices of the Jowa Hill Hook and Ladder Company. The elite of the mining camp were gathered, and among the merry makers were some forty ladies—an unusual number to be gathered in that day and in that country. The supper table, eighty-five feet long, was spread with every luxury that could be procured in the remote mountain town. It was tastefully decorated with ornamental cakes and imported confectionery. The dancing was carried on until the break- ing of the next day. The members of the fire company attended in their uni- forms of red shirts and black trousers. Thomas Montgomery was the man- ager of the principal store in the town —the store that supplied the army of miners that worked in the rich deposits in that district. = Incidentally to the sale of merchandise, the safe in the ‘store was the bank in which scores of miners deposited their gold dust. Mont- gomery was trusted and loved by the “hardy, toiling patrons of the store, ‘Willlam M. Johnson was a gambler, h native of New York City, and a man about 24 years of age. He had drifted to California with the first tide that followed the announcement of the dis- covery of gold, but instead of seeking fortune by toil at the sluices and in the tunnels chose the easier way—he dealt in cards and dealt to win. These two men were among the party that made merry at the opening of the Queen City Hotel. Why they quarreled will never be known. It was between the hours of 1 and 2:30 o’clock in the morning that they had a pre- liminary scuffle, which was quieted by the interference of friends. Thev met again between the hours of 4 and 6 and Johnson asked Montgomery if he thought he had struck him with a slung shot. Montgomery replied “no.” Some few words followed, when John- son knocked his adversary down. John- son suggested that Montgomery get a pistol that they might be on equal terms. Montgomery returned in a short time and the parties met in the street -nearly in front.of the hotel Then Montgomery commenced an at- tack on Johnson with a revolver. At first the weapon hung fire, but two shots were fired without effect. John- son fled into the bar room and in pass- ing out through another door encoun- tered Montgomery, as his friends claimed, unexpectedly, for he assumed that his pursuer would follow him in by the route he had taken. Instantly Johnson drew a knife and stabbed Montgomery four or five times—once in the lungs. Johnson was immediately seized by the bystanders and delivered to Deputy Sheriff Sinclair. The affair created great excitement. The fire company placed a strong guard over the prisoner and the town was guarded to prevent a rescue and to prevent a repetition of the several attempts at incendiarism that had alarmed the populace in the few months that had passed. 1In the forenoon of the 23d word was sent to the various mining camps in the vicinity that a tragedy had occurred and that an execution might be expected. About 2500 per- sons gathered in the town. In the afternoon the hook mnd ladder com- pany called a meeting and selected thirty-two men from whom twelve were chosen as jurors. The testimony was taken, and after being out all night, at sunrise of the 24th a verdict was returned of guilty of “an assault with intent tc kill.” The question was then left to the crowd as to what dispo- sition should be made of the prisoner. ‘When the vote was taken the majority was in favor of hanging him imme- diately. 7 The officers for the execution were chosen, and about noon the prisoner was taken a short distance from the town, up on the side hill, to a conven- {ent tree and informed of the fate that awaited him. A rope was brought and a couple of kegs. One keg was placed on top of the other for the condemned man to stand upon. After the rope was adjusted around his neck an op- portunity was given for whatever re- marks he desired to make. Johnson called for writing material, but as his hands were confined, a friend who was present noted his remarks. His dying sentiments were expressed in a very cool and quiet manner. - He protested in strong terms against mob law, and sald that all he desired was a fair trial under the law before a jury of his coun- trymen. He would abide the conse- quences of such a trial. He stated that some person present owed him $20, ‘which he asked should be paid to some other party to whom he was indebted. He also wished a ring to be taken from his finger and sent to his mother and sister, but his hand was so much swollen from being bound that it was impossible to remove the ring. He re- quested that the rope should be care- fully -adjusted and that he be permitted to climb on the limb of the tree and jump off. This was denied. Then he asked permission to give the word him- self, and that was granted. He was placed on the kegs, the rope was tight- ened and distinctly he counted “one, two, three” and jumped to his doom, thus partially being his own execu- tioner. During the entire proceeding he was perfectly collected and entirely indifferent about his fate. About 2000 people were present at the execuuon. The lynching of Johnson created a profound sensation in the public mind and for a time promised to lead to se- rious consequences’ Montgomery did not die from his injuries, nor did he die until many years afterward. The ver- dict of the jury did not warrant the extreme penalty. Warrants were is< sued for the apprehension of the parties that had engaged in the execution, and Sheriff Sam Austin attempted to serve them. One man was arrested, but was rescued. A posse was ordered out, but no further action was taken. The citi- zens of Towa Hill issued a circular to the people of Placer County, in which they presented the evidenme that had been taken before the People’s Court, the verdict of the jury and the charac- ter of ‘Johnson. It was claimed that the hanging was sanctioned by the de- liberate judgment of some 1500 people. According to the statements in the cir- cular, Johnson was greatly the aggres- sor; that he had dismounted from his horse to assault Montgomery, who was walking quietly along with a friend; and that when Johnson rushed upon him with his knife, Montgomery fired in self-defense. The friends.of John- son presented a counter statement. Speaking of the affair, one of the lead- ing dailies in the State said: “That Johnson was fully as desperate and depraved a character as painted: that he was wholly the aggressor, and made a wanton and unprovcked assault on Montgomery at the time he was stabbed; that he had as fair a trial as a man could be guaranteed in an ex- cited crowd of hundreds we do not doubt, but still the facts stare us in the face that he was sentenced to be hanged for assault with Intent to kill; that he was found guilty, sentenced and hanged by & body of men whose only right was based upon the power given by might and numbers, and that. too, within a few miles of the regularly organized seat of justice of the county, and while the man who was stabbed was living. These facts cannot be sup- pressed; they form one of the chapters of California history upon which our reputation abroad is founded.” In the sharp newspaper controversy that followed this lynching some light was thrown on the past career of John- son. A correspondent sald of him: “He has been a prowling gambler in Placqr County ever since 1851. Many of his fraternity loathed his presence; some _even forbade him addressing them. Men of business forbade him their stores, as he scrupled not to cheat and defraud whenever opportu- nity offered. Hlis name can be seen in almost every business man's baoks kept in 1851-52 in the localities he in- fested. In 1852 a gentleman named Pooley, late of Sacramento, was fol- lowed up by Johnson from Yankee Jim’s to some distance below the Griz- ly Bear House on the divide, with no other object but to rob him of some $600 in dust and to take his life to ef- fect that purpose if need be, for he was armed with a Bowle knife and a revolver. Johnson was secreted in the chaparral half a mile below the Griz zly Bear Houge, and as Pooley ap- proached on f66t Johnson arose, but, opportunely, a team approached, in which Pocley escaped. Two hundred dollars in a purse was stolen from a Chinese gambling-house in Auburn in 1852 one night when the gamblers were busily engaged. The theft was com- mitted by some one rushing in, grab- bing it and disappearing in great haste, The description given by the Chinese answered that of Johnson, who was then hovering about. It was also stated that in 1861 he came near being lynched at Coloma, but by reason of his en- treaties and youth was released on con- dition that he would leave the place immediately, which he did. However bad Johnson may have been he had friends who made a bitter fight to avenge his untimely death. , They were instrumental in creating a strong Sentiment against mob law. The in- cident created an impression in Iowa Hill that has not dled out In all the years that have passed. It was the first and only lynching that occurred in that mining camp. Even now a gray- haired pioneer will be met who will de- clare that divine retribution has over- taken many of the principal partici- pants in this hillside tragedy; that they have met violent endings. WINFIELD J. DAVIS, | )