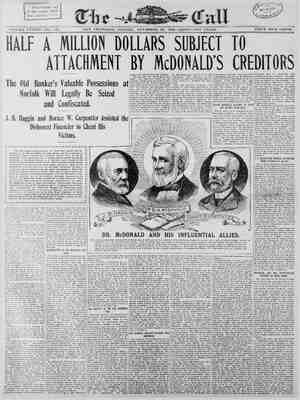

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, November 20, 1898, Page 24

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

24 *M so turrible afraid he's goin’ to keep Thanksg of his kitchen, was in the privacy serious, long countenance more “It looks like it this very mornin’ e o’ raisins on hand for? Bolere Bigg groaned. It Bole gs merely Philup was * to celebrate again this year. the This'll make the third one. I did needn’t tell me Mister Philup a 1 reckon I know that as well it, ar thing as the softenin’ o' time. round in.” For time there was a ¢ and only the sharp little explosions under the stove a bell rang with an impatient twang. “There he goes again!—third time t spices!” On the way his rough softened on the way down, Biggs. Wh & chair at your heel Philip Lattimer s His refined, p ster Philup? ad been sitting to that It alv oke sharply, n the e e spoke. >hillp Lattimer woke cut of a revery at the g accH 3 S e : were cvers .. They hurt him most. “Zounds, man, you here? How long in the name of common “Trere are only two things to do, and then I can get out of it,” ve you been tilting on that chair?” i he n]vx(lex.d : : u rung for me, Mister Philup—no longer nor no shorter,’ There were the flowers to select for the table, and the turkey to i cheerfully. He was used to this. see about. Then, thank the Lord, he could go home—away from the ~ "0, did I ring membe for to-morrow’s ordeal? : HiPea lobken e cheer faded out of poor Biggs' face and left it lusterless. The flowers were soon chosen and ordered sent up. Then Philip the hi . ‘Tlh x“(‘:”{lrj f\:(’l:. 1‘"(!‘4‘(\',f"‘:yn' that I «\.;1 attend to that part—the Lattimer turned wear! toward the meat markets—the very centers them that has,’ turkey. You are to : all th ‘ou understand. I shall have and pivots of all the cheery bustle and confusion. Philip Lattimer ¢ everything as it w Now, go.” A little group of sLabby children had h lted in front of the one them that ha And Bigg! 0000 SHORT STO BY TH HERE is no mistaking the re- turned whaler, just landed with his pock full of dollars after a a profitable cruise. He is not to be seen at the docks, where the | squat, old-fashioned New | curious, Bedford sailing ships lie. Bv the side of the modern steamer, these bluff-bowed, square-sterne Aft look like sur of & prehistoric period of nav But all the same they are strong viceable vessels; y have bitter cold and the crushing ice Arctic for years, and now th slowly di smelling oil, whalebone. But the men who, with infinite toil and hazard, made these great catches are nat there. The ship they have look- ed upon as their home for years has no longer any interest for them. The more modern steamers at the Arctic Oil works are similarly deserted. The whaler has bought himself a new rig- out and is taking in the town. Down on Mission street, close to the water front, you will find a curious lit- tle office. It is modest and retiring. The dingy glass doors bear no indication of the buziz=- carried on within. There bundles of and great 18 simply the name J. Laflin, and that is | all. bounded as to its northernmost end with a high counter. The walls are hung with wonderful and fearful nau- tical prints of a past genetation, In which huge whales are to be seen de- vouring boats at a mouthful, and sturdy ships sail with ease over the top of icebergs. A few roughly dress- ed men are seated on the benches, but no business is going on. “You won’t find the now,” said Laflin. “Try the outfitting houses.” Laflin is a kind of broker or financial agent for the whaleman; h signs him on the articles at the com mencement of a voyage and adjusts the delicate question of ‘lays and shares” at the end, so that each man receives fairly what is due to him. Therefore none know the habits of the returned whaler better than he. He was right about the outfitting houses. The first place I struck was simply crowded with recently landed saflors. Their boxes and bags covered the floor; dunnage of all kinds was scattered about, relics won from the Arctic after a three years’ voyage. There were huge mammoth tusks, care- Don’t that mean Thanksgivin’ fixin's? AS YOU ¢ He's had most tkb sation of the imperative tick of the Kkitchen ‘“PATSY : YOU BOOST HIM.” one without hope. and T as v solemnized ned aloud ened and kitchen, among vegetabl shelves of his neat little pantry there w no pleasant elation on anticipation among his oth pic Once Philip Lattimer v only once. Then it was to s ‘Rémember the little pies “0, ‘e Bolero Bigss, under Li his gettin vep them in th TeL i in’. What'd he say to Biggs, see't there he say what'd he Answer that, if you can, he ain’t erable, Mister raisins settled was unans Th He set to work on the little pies. plates of graduated sizes. They flaky, as little children like them. “Phill; Con placed them away on a shelf. little pies! The 'big grand dining-room we opened on Thanksgiving day now. polish, and the aken and the pictures dusted. Mr. Philup’s library wa Philup could hear everything. and a faint shade face for a moment hope he was gettin’ over it! - kind, Bolero ch a years to come low. monotonous voice, clock and oc lids broke the silence. his evenin’. More raisins an ath, when his master was gone. over them three little grado 1 on it last year—but, lordy, this! He made three of them, came oven brown and e were two days left before Thanksgiving day. 1 es and spicy aromas. illed up from end to end. his face, there was no spice of forgot that!” T w out of the reautiful shining floor as well. Biggs tried to whistle as he s next door to the dining-room and He heard Biggs' plaintive whistle of appreciation lightened the gloom of his bitter ed the kitchen during those two days— tersely: Biggs—three of them, graduated.” groaned Biggs, w I did reckon on ated pies by this time! ort’s an’ the Little Un's,” he told them off, as he How many times he had made those set in prime order—it ‘was only he chairs were rubbed to a new hangings All the “That whistle comes hard—the poor beggar!” he murmured. ‘Biggs spent Rapidly he paused a minute outside. “Now you choose, Patsy. or-r-ful big ’un.” 3 “So do I, too—huh, you s’pose I'm goin’ to choose a little 'un, Minervy Bemis?"’ ~ Minervy was evidently the commander-in-chief. She had mar- shaled her little forces in shipshape order, in a straight row facing the line of dangling turke: All the small, lean faces were thrown back to command a good view. “Now you, S'lome—quick, choose! all da. We've got to go home and cook it. ““The big 'un,” cried S’lome, glibly. “The big 'un! the big ’'un!” shouted all the little sharp voices. “Tken it’s the big 'un, 0’ course. It takes everybody to make a majority. Now, you can all poke him. I'll begin, then Patsy, then S'lome, down to Cornwally—Patsy, you boost him.” One by one in a grave procession they tiptoed up and prodded the great, plump body of the largest turkey in the line with little forefingers. Patsy ‘“boosted” the baby “There!” sighed the commande -chief, “that's done. I'm goin’ in now. Patsy, S’lome, don’t you pinch nobody.” Mipervy and Philip Lattimer went in together. Philip Lattimer was oddly resentful toward the small, brisk little figure. That chit of a child going to buy the finest turkey of them all! She was wizened and shabby—very shabby. The whole little tribe out there was very shabby. Didn’t look as if the lot of 'em together ever ate a whole drumstick in their lives! And here was their governor gen- eral marching in here to buy a costly turkey—the turkey Philip Lattimer wanted. The proprietor hastened forward, rubbing his palms together. “Ah, Mr. Lattimer—glad to see you, sir. Ah—what can I do for you to-gay?” “Wait on the child first,” Philip Lattimer sald, briefly, standing back for the little shabby figure to advance. Minervy felt about nervously in the pockets of her dress, and produced a few pennies. She held them out in her little open hand. “I want them wuth o' meat,” she piped, importantly. “The kind that's cheap, with bone an’' gristle in, you know. If—if you could put in quite a hunk,” she added, rather wistfully. ‘When the bundle was ready she trudged away with it contentedly. In utter amazement Philip Lattimer followed her to the door. “I've got him in here,” announced the commander-in-chief to her little trcops outside. *“Now we’ll go along home an’ cook him. Come on—" But suddenly her eyes flashed indignantly. Salome was look- ing up at the great bird on the line wistfully. “S’lome Bemils, ain’'t you a Didn't T say 'twouldn’t be no fair to look afterwards? pointed in you; yes, I am! What's the good o' makin’ b'lieve if you ain’t fair?” Minervy’s shrill voice was tremulous with growing wrath. S'lome, diminished and ashamed zht up the baby and hid her face be- hind his mop of soft h ‘I didn’t look, Minervy,” cried Patsy, pinching Salome’s arm ously. *I never.” “Nor me neither,” trilled little Grissel, turning her back resolutely to the display of turkeys. ‘“Me neid,” piped Cornwally. Ah! Philip Lattimer turned back into the market slowly. Now he understood the little tableau. The shabby children were making believe. A make-believe Thanksgiving—well, what was his Thanks- giving to be but that? He smiled bitterly, bitterly. “I'll send it right up, sir—right up’—the proprietor was saying blandly in his ear. He heard him distantly as if he were far off in another world, or in a dream. “It's a fine bird, Mr. Lattimer, the biggest one on the street. You're in luck to find it here as late as this. Only come in this morn—" “Do you know anything about that child?” Lattimer's crisp tones. “Child—child, sir?” questioned the man in perplexity. , yes, the child who bought the turk—the lump of meat a v minutes ago.” —yes, that little beggar. No, I don’t know—hi, Jim, ever see that Httle scrub that was in here jest now buyin’ scrap meat?” Jim laughed easily. “See her every mornin’ an’ night. Lives died an’ there's a whole raft o’ young uns. Pa’s a wiper down to the vards—he’s in the horspital. Got pretty nigh wiped out!” or turned to his customer with a wave of his hand. it, sir—whole story,” he smiled. “Yes, yes—the whole story, peated Philip Lattimer, absently. Already his interest in the little episode had waned. That evening a curious whim seized him to go out into the kitchen and watch Biggs dress the turkey. He had been pacing restlessly up and down—up and down, till he could bear the monotony no longer. And certainly he could not bear to sit still. Biggs was whistling gloomily over his work. The great turkey reared its plump side from the dripping-pan on the table. To Philip Lattimer's suddenly awakened imagination the dents of little prod- ding fingers were visible in it. Minervy's—Patsy’s—S’'lome’s—the baby’s—he saw them all. Biggs’ great hand rested for a minute on ths bird’s side, as he plied a needle back and forth across the breast; and new dents appeared. The new ones and the old were much alike, but Philip Lattimer refused to see the resemblance. He had remembered suddenly the whole strange little scene of the after- noon. It built itself anew out of the flickering shadows of the little kitchen and rehearsed itself before him, uninvited. He was watching the row of uplifted, lean, eager little faces again—choosing the “big 'un” among the dangling uncomely turke:; “I choose the big 'un,” the commander-in-chief was shrilling in his ears. “The big ’un! the big 'un!” all the shrill voices were crying. Which one’ll you take? I choose that We ain't goin’ to stan’ here Hurry up!” with evident relief, you keep ’em behavin'— interrupted Philip 'longsider me. Ma's ing that, beginning like a sot:, In whistles Biggs found vent \ 5 " -%es, Mr. Philup. Biggs' voice quavered with someth ended in a queer, ux:icanny whistle. 11 his warm emotions. 5 i’!n thcfl s‘:illness that followed Phillp Lattimer slipped away to his i ks and haunting memories. mm”ll‘h?elg yk']é:x:‘fmree years it had been since he had brooded there s v softening —chutting himself out of human fellowship and the sof ?x:%?fenc:.su[(:fl E It had been three years since he and a light heart arted ways. 2 To-night the heaviness weighed upon him more thanflegerkr{ze could not stifle it in books as sometimes—it could not be stifle 2 ({ a while he gave up the attempt and loosed thev bars 0_}( restraint an let his grief have its own way. Why not? Why not? tonasa atiiis Biggs crept along the hall on his way to bed, and stopp ) master’'s room as usual to see if all was well. The door stood a i aj eered in. s hmso?‘fi.rrd’;'}d Sflé’my he cried, Inwardly, with a tug at his heart- strings. “He's at it ag'in! He's LR'(".d lhe‘ btlt“(;;ls all OHL an that’'s he sign. “He's at it ag'in—Lord, Lord, ain’t there & : 5925 was on his kgees, and might have been praying. The tears were rolling down his creased brown cheeks. Through the opening a chink of light escaped, and made a bar across his face. Within he saw Philip Lattimer sitting with bowed -head before a little row of pictures on the table. He had set them up before him with gregt care—hers first, then Philly's, then Comforts and then the little one’s. The sweet, still faces regarded him serenely—there was no grief, no heartbreak in them, as there was in his. Now and again he put out his hand and smoothed one of the faces—hers oftenest. The room was perfectly still, except for the terrible, dry sobs in the man's throat. “0, Lord! O, Lord!” moaned poor Biggs in his stricken heart. He crouched there in the dark hall, with the bar of light athwart his homely, working features—grieving his master’s grief. It was all the grief he had ever known, but it broke his heart. “Lord, Lord, couldn’t you a’ took ’em one to a time—one to a time, Lord? He might a’ got over-it then. Look at him in there, touchin’ the faces—now he's touchin’ the Little Un's. Look at thg Little Un smilin’ back! An’ she’s a-smilin’, too—they're all a-smilin but him. He's makin’ them awful sounds in his throat. O, Lord, I do’ know but it'll kill Mister Philup! If I could jest cry for him—" Biggs was crying for him now. He let his big ungainly body slide noiselessly to the floor and curl up in abandonment of sorrow. But he made no sound. Inside the quiet room the faces in a row smiled on happily—and Philip Lattimer sat on before them hour after hour. He lived over all the tragedy of his life, scene by scene. Once, with one of his sudden whims, he drew the pictures into the playing of the tragedy. When she had died, he put out his hand and turned her sweet face gently downward on the table. Then Comfort’s—Comfort had.come next—and then Philly’s picture and the Little One’s. He had had the Little One the longest—but she went, teco. Afterward he put all the pictures back again in their row. It was late into Thanksgiving morning when he went to bed. Biggs went a minute or two before—he had just time. Thanksgiving day was clear and brisk and sun-flooded. There was joy and thanksgiving in a thousand homes, and in the others— God pity the others! In Philip Lattimer’s home there was a ‘“make-believe” Thanks- giving. Biggs worked steadily and faithfully, whistling all the while. He arranged the beautiful table with neat precision. He let in the sun- shine upon all the dainty glass and silver, till they dazzled his reddened eyes and hurt them. The flowers came and were arranged as Mister Philup Iiked them—roses at her plate and little Comfort’s, and gay, bright flowers at the Little Un’s and Philly’s. At last everything was ready. “‘But he ain’t,” muttered-Biggs. ‘“He’s gone out—I see him goin’ a spell ago. He was stridin’ right along, with his shoulders dreadful high an’ square. He never done that before.” Biggs went back to the kitchen and waited. An hour past the time appointed he heard his master coming in, and “Lordy, lordy, if there ain’t somebody with him! There was—hark—O, Lord, little voices! Little voices.” Biggs stole out into the hall and listened with a startled face. A subdued chorus of excited little voices reached him and one above the other was saying, admonishingly, “Step easy, all o' you—don’t you see there's flowers in the carpet? Step round ’'em if you can, like I do. They won't smash, but it don’t seem right to step on 'em. There, while the Kind Man’s gone upstairs, you all listen to me— I'm goin’ to talk.” The high, imperative little voice “carried” easily to Biggs’ aston- ished ears. He heard every one of the slow words, with pauses, for emphasis, between them. “Listen!—if there's butter—to your—bread, don’t none o’ you— look—surprised! ~Spread it on—kind of—indiff'rent, if you can. If there's turkey—" Turkey!"” shrieked all the other little voices. “Sh! -he'll hear you. If—ther’s—turkey, eat it slow as if you'd always eat it since you was born. That's all.” “But we ain’t ever eat it, Minervy Bemis!” np cauadie vou aln't ever? Can't you make bilieve? e smal eet shuffled about nofsily. - voice began again, y. Then the motherly little “When it’s come time, you go ahead. Patsy— s then Gylssel. I'm go}n' clear behind where I can 132§“a{°t‘;{e Srel':{ng; ry minute. I'll take the baby. Sh! the Kind Man's coming® m, are you standing up for when there’s with short n e face was set in unbroken gloom. of a chair five minut Yes, yes, it was about the turkey. Now I re- : | friend zing huge casks of evil | Inside is a large, square room, | whalers here | led y. Their faces were father coming from the station faced, staring little count mother not selemn. Now ous jerks in his with a wait- for her dinner to-morrow. mothers and the little children. he selected. Their shrill, high voi roaned intermittently, RIES TOLD E RETURNED WHALERS canvas; mountain whal tusks. It was these tusks which furs and skins | caused all the trouble. The skipper got along with his repacking very well, for fully wrapped in | sheep and deer hor | in every variety. The fat little Jewis proprietor had much ado to get about his own store and transact any busi- at all. the most curious sight was the | ., a great, burly, blue clad man, off in a hurry to visit his the B For this purpose it wi ack his belongings in a uitable for a long car jour- ney. Obviously the chest he had brought ashore with him would not do. It vod in the center of the store, a mas- ve wooden structure, as large as a 11 house,” and weighing about half | a ton. ! “They charge 50 cent a pound for ex- | tra baggage,” growled the captain. “It| won't do. Bring me a trunk.” An obliging salesman produced a | modern trunk of the usual pattern. When the skipper threw open the lid of his box—it had once been the ship’s trade chest—the most astonishing col- lection of odds and ends was revealed to view; all the leavi of a long voy- | age. There were pip and tobacco, | packages of medicines and herbs, deer skin coats and moccasins and,most | prized of all, 2 very fine pair of nar- g WITHIN | “THE BOAT _APPROACHED | TWELVE FEET AND THE BOMB WAS | FIRED.” | he packed after the simple masculine | method, which is to throw the bundles of clothing or what not into the box | and stamp them down with your foot. | The trunk was nearly full when he | came to the narwhal tusks. and here | he stuck. No device known to nautical | ingenuity could induce these tusks to | fit in; whichever way you tried them, | they were alwavs just an inch or so too ) | long. There was nothing for it but to begin all over again, and. as the re- | sources of the store were exhausted, to | ransack- the town for a Saratoga of suitable proportions. On the benches around the wall sat the less important men, mates and boat 1steerers and so on. They all wore new | clothes of a distressing similarity in cut and pattern; their shirts were of soft striped silk, their neckties of gor- geous hue. They were all sober and sedate, with fresh, clear complexions and tough and wiry frames, as become men who have spent their years in a healthy open-air occupation. g They talked willingly enough about “THE BLIZZARD CAME UP SUDDFNLY AND THE HUNTERS WERE LOST.” e afternoon preceding Thanksgiving Philip Lattimer put by and went out among the holidaying crowds on the streets. him and peered—some of them—into his solemn face, and then he v children—or a big son with his old father Now and then he met a house-mother out for the last And children—children ‘What kind of preparation were they es assailed his ear insis P EPEPOPPOPPOPOOPORPOPOPOPCRPPRPPOPPEPEPPPOO® fat met a following of eager- when the child, siving—" “Bigg: me, M “No, I never.” tently, as how many more? Salome, dangling still above his not been equal to the cruel strain upon it. round quick Then he saw them stretching up on tiptoe to touch the big 'un’s des—there were the little dents they made now. Ana last of all in the little drama of shadows, he saw the look of keer resentment on Minerv, “What's the good o’ s face and heard her cry in making b'lieve if you ain’t fair?” had looked bac Poor little Lot’s wife! head. Her " Philip Lattimer said, abruptly. ster Philup. ou ever make belie e anything in your life?” “Then of course you never made believe a Thanksgiving?” The lamplight on his face showed “I vever, Mister Philup. There's rious smile. aid, gently. niled gravely, too. “Yes, yes, wistfully at the big 'un Making believe a Thanks- Biggs There are men and little children, and w It's hard work making believe, Biggs.” @9@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@G@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ where are you, you rascal? man!" dignantly, That was faith had “Bolero Biggs,” he cried round!” Then Biggs heard Mister Philup’s steps. the stairs and joined the little shuffling steps below. were turning toward the dining-room—O, Lord, Lord! “‘Biggs,” called Philip Lattimer’s voice steadily, Biggs hurried back into his kitchen with wonder in it was drowned in joy. s et L They came rapidly down All the steps “Biggs, Biggs, Why don’t you serve dinner? Stlrggs. The exultantly, “do you hear, he's comin® In the great, brilliant dining-room the strange Thanksgiving din- ner began and proceeded slowly. the table, with the stamp of indelible pain upon his face. and refilled all the little plates with a steady hand and. now and then, on the little rank and file of beaming faces The other faces that looked up at him out of the moist, sweet flowers and shone dimly in the shimmer of sunlit silv 4 were smiling, too—serenely, as they had smiled at him o there's knows of pictures in the night. their adventures in the Arctic, making, vessels do not consider this latter prod- | the cask,” observed an expert, “it will light of the hardships the long northern winters. “It's not the cold one minds so much,” said an officer. “It's the mo- notony of being shut in so long, with nothing to do all winter. Once the ship is properly fixed in the ice undi covered in, with snow banked up all| around her we just have to sit down and wait and keep warm as best we can. We play cards and gamble and read all the books there are on board, but we get awfully sick of it all | There’s not more than an hour’s work | a day for each man to do. We have to ! | | haul fresh water ice from the shore, | keep the ship clean and so on, but that is all. Now and again, when the weather is fine, we go hunting, but it | is risky work. ‘If a storm comes on while you are away from the ship you stand a very | good chance of being frozen. Tiwo men from the Grampus lost their lives in ;this way. They were out hunting with a party, and when we got them back on board their case was hopeless. We did everything we could, but it was better for them to die. They were so badly frozen that, even if they had re- covered, they would not have had much left to live for. When a man loses al his limbs and various other parts of his body it isn’t much use living.” But in an ordinary way, for these strong healthy sons of the sea fros bite has little terror. Nearly all the men around had been frozen slightly generally in the face or hands. “I got | my nose frozen once,” said a fresh- | faced young fellow, “but it's all right now.” The man’s nose was of the normal | size and covered with clear, health | skin, so that it is evident frostbite, un- | less very severe, is not such an awful thing after all. “The great thing,” remarked another, “is to wear deer skin clothes, with the hair next to your skin.” Now this is contrary to the advice of all the doctors, who assert that under- wear should always be made of flannel. Yet these men of experience are warm in their praise of fur. They claim that the electricity from the hair imparts it- self to the body, and keeps up the tem- perature. But the skin worn must be from a land animal; the coats of seals, walrus or other sea-keeping beasts lack the requisite warming qualities. If a whaler can keep himself warm he has practically solved the problem of existence in these .inhospitable re- glons. Otherwise there is little dan- ger, for the pursuit of the whale is sad- ly lacking in excitement. The bow- head is a timid, gentle creature, widely different from the courageous sperm whale, which has wrecked so many boats in southern waters. Yet the| bowhead is the most valuable of the | Arctic fishes, for a single head will often yield 2000 pounds of bone, to say nothing of the oil which may be ob- tained from the carcass. Yet many| Still, at the Arctic Oil on Mission Bay, you will see great tanks full of whale oil, which is to be manufactured into all sorts of lubri- cating compounds. And in the yard there are thousands of pounds of | whalebone drying in the sun, getting ready to stiffen the corsets of European fine ladies. For as yet the Parisian dressmaker has discovered nothing “THE MEN |UMPED AS THE BIG WHALE CRUSHED THE BOAT IN ITS JAWS.” which will take the place of whalebone for this purpose, and hence the price is maintained at a satisfactory level at about $3 50 a pound. Many curious virtues are claimed for the Arctic climate, not the least being the curative property of extreme cold. “There was our mate,” said one sailor, “whose hands were doubled up with rheumatism before we left, yet, when he returned he was perfectly cured.” Perhaps the entire abstinence from all alcoholic stimuiants may have had something to do with this re- sult, for on board whalers the temper- ance rule is strictly enforced. At least it is so stated in the articles, no man being allowed to take on board any form of distilled liquor. Yet there are whispers of a certain mixture known as Duffy’s brew, compounded of potatoes, raisins, apples and anything else that comes handy. Its intoxicating proper- ties are highly commended. “If you put half a plug of tobacco in | Works, down ndured during | uct worth securing; the whalebone is | stiffen the whole crew.” | the great prize. It is remarkable, considering the ‘hazardous nature of the occupation, | that there should be so few accident: | The boat-steerer has to balance himself |in the how of a slippery, tossing boat and hurl the heavy harpoon, with a gun attached to it, through the air. As | soon as the iron pierces the whale, it | fires automatically a dynamite bomb | into the carcass of the poor beast. The whole instrument, with the inch and as | half Manila line attached to it, weighs |at least fifty pounds. I asked a boat- steerer how far he could throw it, and found out, by practical deduction, that about twelve feet was iis limit of effective range. So that the boat must be within twelve feet of the whale when the attack is made. Yet the pacific bowhead never makes any active re- sistance. He simply sounds when he is struck, and it is only a matter of time and line to kill him. | “It’s different with the sperm whale,” ! sald an old boat steerer, who has fol- lowed the profession for thirty vears. “When I first went whaling in the Southern Pacific we lost lots of boats and sometimes men. Once off the coast of Chile we made fast to a big sperm whale. Instead of sounding he simply turned and charged us with wide open ! mouth, his huge jaws completely tak- ing in the boat. I can tell you we jumped out of that boat in a hurry. We lost two men, though, because they | could not swim well enough, and it was some time before we were picked up.” | _Though Arctic whaling has none of | these thrilling moments, there is quite Philip Lattimer sat at the head of but he filled smiled down er and giass ut of the row That was not make-believe, ANNIE HAMILTON DONNELL., enough discomfort about the 1 make it an ungpsirable m:cupf:-lrteu):l0 Men facing all the Tigors of this north- ern clime ought, one would think, to be very highly paid. Yet it is seldom that the hsailors lcome back to port with much to their credit. It is of’;hance‘ all a matter his year many of the vessel 1 made splendid catches, and the ssa!l’lno o on the Grampus and a few other ships will have about six hundred dollars to their credit. From this, of course, must be deducted the advance before the voyage started, and the heavy demands of the slop chest. A sailor’s “lay,” or share of the total earnings, is only one two-hundredth. A boat steerer gets twice as much, and so on up to the cap- tain, who claims from one-twelfth to one-fifteenth of the total. The ship owners get the balance, which may amount to one-half the catch. All sailors, however, are not so lucky as the men of the Grampus. Here is a typical case of bad luck, told me by a boat steerer who had been absent for over four years and a half in the Arc- tic. He sailed away in the Wanderer, after getting an advance. He remained by the Wanderer thirty-two months, during which time they caught four whales, his share being $175. Then he joined the Newport and cruised two years in her, the result being only four whales more. He returned here in the Thrasher, which had no whales at all. Now, all that is coming to him by way of compensation for his years of toil in the most awful climate in the world is Just $80. Who would not be a whaler? J. F. ROSE-SOLEY. Away From The Rabblt--Say, won't you catch it fer stayin’ out so late? The Cub—Naw, my mother’s hibernatin' yet!—Truth. His Mother, and won't wake up for two months