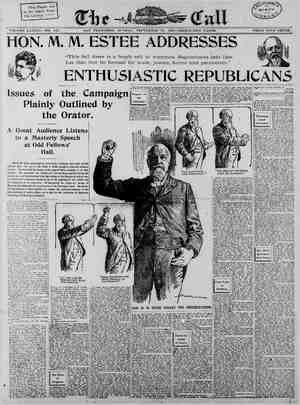

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, September 25, 1898, Page 19

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE ‘SAN FRAXCISCO CALL, who retur years after the time w have been lost. It appes ran the gamut of savage experi on a tiny island to the chiet of tralla. His story, the most rem: thirty Every Morning | Anxiously Scanpned the Horizon for a Sail.” HE ation of the hour in Europe is M. de Rougemont, Robinson Crusoe, ed to France a short time ago, more t en he disappeared, and was sup] ces, cannibal able of modern times, has deeply the “modern during this time N de Ro from that of the lonely castaway tribe In the interfor of Aus- nter- ested such men as Drs. Keltie and Mill, the eminent geographers, who have investigated it and are sati attraci any ied of i week he appeared g published cement with last mont the man of the hour. The title of nerally a great deal of attention wherever he appears, and has rec r of invitations to address geographical and scientific socie- before the Bristol Congr: i of erially in George Newnes’ Wide World Magazine, Altogether M. de Rougemont may the modern Robinson Crusoe, which has placed upon him, is in no way a misnomer, for the weird M. de Rougemont red perfect accuracy. s of the Bri h His account of his cience. be called nd remarkable experiences which he has been through have never been so carefully verified: 1563 T left home a mere aged in a pearl-fish- T board the Dutch er Veielland. Our pearling unds lay between the Australian and Dutch New Guinea. After s the v was 2 .aall coral island, situa- thirteen - degrees south and ast, off the northwest coast y alia. 1 was absolutely alone, ve that I had the captain’s dog with N th on isl thi or, rather, sand-spit, and underwent ring. At the end of that e a party of blacks, who had been from the Australian 2 cast upon the island on a raft, such as is used in fishing expeditions. After a further period of two years, h suffc = Defoe wrote the story of his famous hero. nt is the first account that M. de Rougemont has and covers briefly the whole ground that will be the numerous installments of his magazine story. t he related to the British sclentists, the truth of which has It is the who found their way back with me from the little islet by steering by the stars. For some little time I remained in the eamp of their tribe, where I was received in the most friendly way in consequence of the introduction and representations of my native wife. This woman was one of the family of blacks that had been cast upon my islet. When we landed nearly all the mem- bers of the tribe and many individuals from other tribes were gathered to see the first white man they had ever be- held. They were not-so much sur- prised, however, at my personal ap- pearance as at the form of my foot- prints, which differed very greatly from theirs, and the few articles I pos- sessed filled them with amusement, es- pecially my boat. This -koat, which I built on the island from the wreck and in which I reached the mainland with the party of natives was, unfortu- nately, lost in an encounter with a whale, and with it disappeared my “| Drove the Ravenous Sharks Away by Beating the Water With My Oar, and so Reached the Unconscious Castaways.”” six months’ walting for favorable winds we set out together in a boat buiit from the wreck of the schooner, and I landed with my companions on the coast of Australia in the year ]866—the exact locality was C(ambridge Gulf, on the northw coast. Of course I made many excursions in various directions, always with the hope of reaching civi- lization, either overland or by sea. E ntually, however, 1 drifted into the center of the continent, and only ached civilization in 189 after an ex- ile of upward of thirty years. When 1 first landed on the® Australian main it may be necessary to bear in mind that I was absolutely destitute— without clot tools or instruments of any Kkir a stiletto Testament in the French sh languages; all maps and ad been swept away by the hat preceded the wreck. I Dt anc charts heavy seas & had no writing materials whatever; it was therefore impossible for me, even if at that time I had had the wish, to make any scientific vbservations, or to record my wanderings. For a time, however, I did make notes on the blank jeaves and margins of the Tes ament, using blood for ink and a quill from a wild boar as a pen. This book was, un- fortunately, losi after my return to civilization in the wreck of the steamer Matura, which was lost in the Strait of Magellan in the present year of 1898, When I landed on the continent I believe vast tracts of it were unex- plorei and certainly my own knowl- edge of Austranan geography was very small and vague. If I'had known even the exact outline of Australia it would have saved me many terrible journeys and years of suffering. As I have already said, I landed on the east side of Cambridge Gulf, as nearly as I can. now remember, that is to say, Queen’s Channel, which was the home of my native companions, hopes of reaching Somerset at Cape York, a settlement of which I had often heard the pearlers speak. Thus 1 was obliged to make the attempt by land, and I started with my wife about October, 1867, intending to travel due east to the Queensland coast. After eix or seven months’ traveling —at first over a flat coast land diversi- fied by isolated hills and then through an elevated and very broken country— I reached a desolate and waterless re- glon covered with spinifex, where we both suffered terribly from thirst, and but for the skill of my native wife In finding water and procuring food I should probably never have come through it. We soon found that we had come considerably farther south than we in- tended, and so we struck due north, and eventually reached a flooded river flowing eastward, which presently led us to the sea. This river was probably the Ropa, entering the Gulf of Car- pentaria, but as I did not know of the existence of such a gulf, I belleved we had reached the Queensland coast, and 1 at once inquired of the tribes we met for the nearest settlement of white men. These natives, by the way, were the most savage and hostile I ever en- countered in all my wanderings. They attacked at night; but having been warned by my native wife, we retired from our gunyah or shelter of boughs, and slept In the bush without a fire. In the morning we would find our shel- ter riddled with spears. In reply to mv inquiries, for these people were appar- ently frlendly in the daytime, they pointed to the southeast and to the northeast, indicating that settlements were to be found. Then, after staying a few weeks with the tribes living on the islands near the mouth of the Ropa, probably the Pellew Islands, I set out in a frail duz-out, borrowed from these tribes, to ascend, I believe, the Albert River, but on account of the floods which at that season affect all the rivers on HOW I WAS CAST AWAY ALONE AMONG THE SAVAGES OF THE SOUTH SEA SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 1898, ISLANDS FOR OVER 30 YEARS. FEIFE LA+ Tried for Thirty Years to Reach Civili= zation, Married a Native Cannibal Woman. Found a Lost Ex- plorer in the Wiids. R R R R R R S R R P R R R R R R R RS Sy Sy the coast, I changed my mind. I then determined to coast along to the northward, hoping to reach Somerset, and having not the slightest idea that the great Gulf of Carpentarta and Cape York peninsula rated me from the Pacific Ocean. The smalin of the craft, which quite unfit to 80 far beyond shelter, and the nece: ty for keeping a close lookout for a set- tlement, compelled us to follow every winding of the coas At length, after several months of coasting, we found the land trending to the west, and here at Raffle’s Bay we found a Malay proa. The themselves, who were beche-de- hers, were willing to take us to Kolpans. but as my native wife had a great dislike and distrust of the Ma- tle inclination to make another at- tempt, and for three years I lived among the natives, becoming accus- tomed to the life and finding it not dis- agreeable. I was interested in study- ing their customs, and the customs and languages of their neighbors. For this I had a motive. In those early days it was always my object to make the ac- ance of tribes who could render nce in escaping overland. re to reach civilization re- and about the ear 1873 I with my wife, resolving this the continent to the started time to cross south, as I knew In a vague kind of way that there were great towns on the coast somewhere to the south. I had only the very haziest idea, how- ever, of their position. On our way south we first crossed a range of gran- ite mountains running east and west. After crossing this range we came to a low and slightly undulating coun- try covered with dark chocolate col- ored loam of great depth. I found here a most extraordinary richness of vege- tetion and animal life, especially a kind of water rat. I found creeks with very deep channels cut in the soft, rich loam. We were, I should think, about a week crossing this rich country, com- ing more or 1 outh. The tribes were very numercus, and altogether it was very thickly popu- lated. I never traveled due south, but found it expeditious to go from tribe to tribe and from water hole to water hole. As far as possible I kept on my BY LOUIS DE ROUGEMONT. PR R R R R R R e + + ! Was Made a Can- ? + nibal King. + ¥ Amassed an Enor- § + mous Treasure in + + + + Pearls. 26 ! Rode Wild Turtles } + for Amusement. : + R R R R R R e of all resemblance to a European. Re- pulsed in this way more than once, I despaired of ever making my real character known. Two or three weeks after the en- counter my wife came upon the tracks of a man whom she described as a White man, and as a man no longer in his senses. She deduced this latter fact from the eccentric circles which the tracks followed. Following up these tracks we did find a white man alone and dying fro.. thirst. He was hope- lessly imbecile. He lived with me for two years, a serious incumbrance, and never regained his intelligence until just before he died. He asked who I was and where he was and then he sald his name was Gibson, and that he had been a member of the Giles expedi- ‘Every Day I Performed Extraordinary Acrobatic Feats for Them, and so Held Their Wonder and Awe lays, and could not be prevailed upon to go, I felt I could not desert her so for from her own people, and I also considered she had already saved my life a great many times; thus the op- portunity passed. Here at Raffles Bay we met a native who spoke English and who had served on a British man-of-war. He told us of the settlement of Port Darwin, lying to the southwest, and he warned me to avoid Van Diemans Gulf, partiy on acount of the alligators and partly, also, on account of the innumerable creeks I should have to ascend in search of the settlement, for it must always be borne in mind that none of my informants gave me exact and pre- cise information, some of them simply indicating the direction. We landed on the northern coast of Melville Island, and after we had agaln reached the coast of the mainland through Apsley Strait we experienced a terrible storm, which must have driven us past Port Darwin. For whole nights my native wife and I would be immersed in the sea, clinging to the gunwale of our frail craft. At last, about. eighteen months after we had left my wife's home in the Cambridge Gulf region, we one day recognized certain islands and also the coast, and soon afterward we found ourselves, to our great surprise, at the very spot from which we had started. Of course, I had to pretend that my return’ was anything but In- voluntary. ¥ The next attempt I made was to the southwest, starting after some months of rest, and coasting in the dugout as far as King Sound. I landed upon and explored many of the islande dotted along that extensive stretch of coast, and in some of them I found caves with rude drawings on the rocks. On what was probably Bigges Island I found a cairn of stones, which I readily saw must have been the handiwork of a white man. ‘We returned to the old camp over- land, crossing the King Leopold Ranges, which were finely wooded, and appeared to be largely composed of granite. Beyond those ranges the country was a moderately elevated plateau, intersected by many very fine creeks and rivers, and covered with long grass from twelve to fifteen feetin height—so high as to make traveling difficult. We even had to fire it to clear a track. There were also on this plateau a number of curious looking abrupt pinnacles of bare rock rising above the general level surface. We next struck an undulating country, covered with sharp broken pebbles of white quartz, with ledges of slate creeping out. In this quartz I saw gold for the first time I had ever looked upon it in its native state. We n>xt struck what was probably the Orde River, which we followed down to Cambridge Gulf, and returned along the coast to our own home. On returning from- this journey I felt lit- own course, bidding the tribes adieu when our ways lay in diametrically op- posed directions. Besides having my native wife with me I was armed with a certain mystic message stick, and, best of all, T had the power of amusing the tribes by means of acrobatic per- formances, my steel weapons and the bark of my dog, who could also go through a little performance on his own account, dancing to the tune of my reed whistle. I emphasize these things because they saved my life over and over again; somenow I always managed to ingratiate myself with even the most hostile tribes. When we had been three or four weeks out we traversed.a rough coun- try of low limestone ranges, abounding in caves, in contrast with the granite ranges - further north, in which I had found no caves. In these caves I found bones, also the skull of a kangaroo, which was so large that at first I took it to be that of a horse; its skull was probably two or three times larger than the skull of the largest kangaroo I ever saw. It belonged probably to an extinct species. In traversing the desert belts, which we crossed on this journey, and indeed at all times, we were in the company of the various tribes we met, conse- quently our course was often east and west instead of directly southward, ac- cording to the water holes, the nature of the country and other circum- stances. Thus we wandered from place to place, sometimes accompanying par- ties of the natives on their hunting and fighting expeditions, but always mak- ing for the south whenever possible, crossing ranges and desert tracks. In the desert country water is ob- tained from the roots of the Mallee tree, a species of eucalyptus. The roots, which lie near the surface, are dug out for a length of about twelve feet. They are about two inches in diameter, and .are cut in lengths of about two feet, and sucked or allowed to drain Into a vessel or skin water bag. These roots yield pure and refreshing water of a slightly earthy flavor. ‘When we were perhaps seven months out we came suddenly upon four white men. At this time we were with a small party of blacks, who were on a punitive expedition.’ The party had al- ready been attacked by these same white men and had retaliated, and therefore they were by no means dis- posed to be friendly. Naturally, in the excitement of the moment, I forgot that I was virtually a black man my- self, and rushed upon them, but they promptly fired upon us and retreated. I now know them to have been the Giles expedition of 1874. I should point out that I was perfectly naked, like the savages, and was anointed withthe same protective covering of black, greasy clay, which is used by the na- tives to ward off cold and the attacks of insects, but, apart from this, the sun had long since tanned my skin out tion. The place where he was lost was, I now understand, called by the Giles expedition “Gibson’s Desert,” and it lies in the southeast of Western Aus- tralia. After Gibson's death I made up my mind to end my days in solitude, and the reason for this was partly ‘that I seemed doomed to disappointment every time an opportunity offered it- self to return to civilization and part- ly, also, on the urgent solicitations of my wife and the tribes with whom I lived. They pointed out to me that I had everything a man could want and that I could be king among them. It was moreover quite evident to them that my fellow white men did not want me. Thus for something like twenty years I made my home with them in the mountainous region near the cen- ter of the continent, where I ultimate- ly became king, or ruler over a num- ber of large tribes. From this moun- tain -home I made frequent long jour- neys, and traversed at one time or an- other a great part of the interior of the continemt. Once I foilowed on the camel track of a white party with the tribe for the purpose of picking up empty tins and for other things useful to us, and I came upon an Australian newspaper. I remember it was the Sydney Town and Country Journal, bearing date some- where between 1874 and 1876. It was a surprise indeed. I read it over and over until I had learned it by heart, and I preserved it in an cpossum skin cover until it was literally worn to pieces, Much of the information this news- paper contained puzzled me greatly, and I nearly worried myself into in- sanity over a statement that “‘the dep- uties of Alsace and Lorraine had re- fused to vote in the German Parlia- ment and had walked out.” Turn it over how I might I could not under- stand how the representatives of two great departments In my own country could possibly be in the German Par- liament—knowing absolutely nothing, of course, of the war of 1870. The tribe over which I reigned was composed of beings who were certainly low down in the human scale, but at the same time they have elaborate laws, which govern their daily life pre- cisely as in the case of clviized peo- ple. Briefly described, they are sav- ages, repulsive in appearance, who have not even risen to such a point of civilization as to have permanent houses, addicted to cannibalism, and altogether of a very degraded type. But, nevertheless, I must say that’they have many ~ood qualitles and that their code of honor would bear com- parison with that of any civilized na- tion. # Although no permanent houses were erected, the natives with whom I lived did bufld habitations, which they oc- cupled during the two or three months of cold weather. These were made of sticks driven into the ground, around which branches, twigs, roots —and brushes were interwoven like a basket. The spaces in the walls were covered with mud or with the material uged in the construction of the white ant's nest. In cold weather the huts were lined with emu and kaugaroo skins, and they are much more comfortable than can probably be imagined from my description. Frequently the number of these huts gathered together in one place forn a large village, though at other times the communities split up into tribes of twenty or thirty families each. Each family, on the aver: , consists of one man, three women and five or six chil- dren, so that even a single tribe makes a very considerable gathering. While mv natives did not, as a rule, paint the body, on greai occasions, such as corroborees, initiation ceremo- nies and other festivities, they paint and decorate themselves elaborately, each tribe having its own design of decoration, and even a geometrical de- sign for each ceremony. The pigments used In decoration are of many colors, but chiefly yellow, red, white and black. Ordinarily the only clothing known consists of a coating of greasy clay, mixed with charcoal. This serves many purposes. It keeps off the cold during winter and is also a protection against the attacks of ‘insects. In sum- mer a special kind of pigment is used to keep off insects, and this material is scented with a kind of pennyroyal. They occasionally stick on to this clay clothing the feather-down from cockatoos, geese, ducks, turkeys and other birds. This serves as a further protection, and when they want to im- prove upon the touches of red, they use blood obtained from the arm of a man. 1 Other ornaments are the wing and tail feathers from all the large birds, such as the emu or native ‘companion, these being worn in the hair usually. They also make use of feather turis on the breast and shoulders, while the bones and teeth of animals are made into jingling necklaces.. From this brief description, it will be evident that my subjects presented a most fantas- tic appearance on full-dress occasions, and it must be added that they are cannibals. Cannibalism prevails to a very great pear that my natives were not a pleas- ant people to live among. But I found the reverse to be the case. They were always che ient and deferen- tial in the rful, ol le to devise h were at 1 to pass the time. For amu: A used to search the heds of the wa for curious stor In a great th R er-courses 1 found th coarse a d, and the cr were: e rich in alluvial gold. In som bed of cement or con Ve at the bottom of a cre he sides, whi vas a large proportion "o that precious metal in the concrete. I frequently pi d up large nuggets, cases a found promptly gave them away to some chil- dren wherewith to amuse them. Al- luvial gold was found to the north of my mountain home, and reef gold to the south, the richest deposits of all occuring in the southwest. In several localities we found low ridges of iron stone mixed with red clay, very similar to those I beheld in the vicinity of Mount Margaret when I reached civilization at these Western Australian gold flelds. Among these iron stone ranges broken iron stoneand quartz were lying in immense heaps or hillocks, and in almost every piece of stone coarse gold could be seen. There are thousands of tons of thi auriferous stone. Lying on the sur- face, in another locality, an iron stone formation stands up above the ground to a.height of about four feet; it is twenty feet wide and over three hun- dred in length. In all the depressions of water-courses in the neighborhood both coarse and fine gold is plentiful. The surface here for some distance ap- pears to be full of gold. In another district I found large quantities of native copper lying about in pieces. All these localities, though far removed from a settlement, can be reached without much dificulty by properly equipped transport parties, and I hope before long t@ have the sat- isfaction and reward of leading the first prospecting expedition to exploit them. My w-d life came to an end at last. “lI Was Obliged to Take Part in the Orgies of the Corrobore.” extent, but is governed by many rules. Usually it is the slain victims in bat- tle that are eaten by the victorious side, and as the object seems to be to ac- quire the valor and virtues of the per- son eaten, I endeavored to wean the tribes from cannibalism by assuring them that if they made bracelets, ank- lets and necklaces out of the dead man’s hair they would achieve their end equally well. When a family grows too large, and the mother—being the beast of burden —is unable to carry one of the chil- dren, the father orders it to be clubbed and eaten. This, however, is entirely actuated by love, as the natives have a horror of natural decay. Maimed and deformed_children are also killed and eaten. Women and people who die a natural death are never eaten. ‘When a man hes to be eaten there is always. a grand corroboree. All parts are consumed, the brain, heart and kid- neys being considered special delica- cies. Some of the bones, such as those from the ankle, are used as ornaments. Often they are strung together to form jingling necklaces, but they are chiefly made up into war belts, which rattle when the owner dances. Other bones are used in connection with sorcery to bring about the death of enemies, and these are known as the death bones. The skulls are kept and hung in trees to commemorate t}? victory, but are never carried about’ Any bones that are left are burned and are never given to the dogs. Human flesh is not prepared or cook- ed in' the usual cooking places, but a special fire s made for the purpese in an oven dug in the sand. The natives are not ashamed to con- fess cannibalism, nor is an individual considered unclean after joining In a feast. Fx:am this account it may ap- An epidemic of influenza swept over the country and carried off my wife, who had in the most literal e been my guardian angel for so many years. My surviving children were also swept away. y Thus left alone, without the old in- - terests that had made life tolerable, I determined to make a last effort to reach my own people, and leaving my mountain home I set out for the south- west. On this, however, as in all my journeys I never able to take a direct lipe, but had to go hither and thither with the tribes among whom I was sojourning. After a time I found a tree markea Forrest, the name of the explorer whq had passed that way, and turning south I at length met a party of prospectors many days north of Mount Marga, the nearest camp. = Taught by bitter previous experience I knew that before I could appear among the whites I should have to get some of my natives to procure some clothes for me by any means known to them. When at length I presented myself before the white men I am afraid they did not at first look with favor on their guest. I answered thelr questions and when they heard I was without mates and had been journeying. hither from the interior for nine or ten months they were convinced 1 was a person of weak intellect. A question of my own, “What year is this?’ convinced them alto= gether that they were right in their conjecture. However, in the end I obtained help and work, and in 1895 I reached Mel- bourne, whence by slow stages and not without many difficulties I got back thig year to Europe. LOUIS 'DE ROUGEMONT.