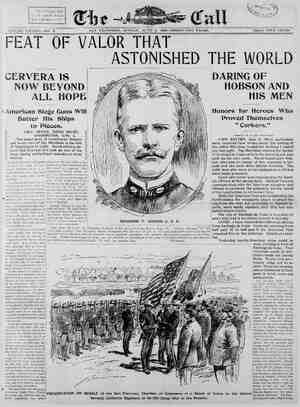

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, June 5, 1898, Page 25

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SAN FRANCISCO CAI;L, SUNDAY, JUNE 5, 1898. o i se. when the second bottles of beer mmanded silence apd leaned ttle table of Mother Revell's manner of an accustomed after- axcuse me bowldniss,” said he, “but oi'm rpouse hilth an’ long loife to Misthress tther be namin’ her Mother Revell whole rigiment names her, more ried the newly made sergeant, patting a hand of a bofled looking iry work in the old troop. “Good cried old Fin S the farrier. Wait till 1 g pencil to report that speech.” nt ould bl z couldn’t 2 be doin’ spakin faith, pril an imes over. ver mothe bin me ache a in’ owin' ms_ginerally, s bor-rn wid Johnny-come- dnifowld blessin’ Martin e, o rgint Revell—yez'1l thank yer mother, fur wt bin the bist frind uy ivery man he ‘ould th wuz in frocks, me son, saved bobtail discharge, an’ n hell, Go iss he An' what we r Mother Revell an’ her boy ain’t worth ' begob! Thi 1 now yez can blow Strait, fur oi'm in croaked. m no orator like . because I've t say. Only to wet Martin's str ’1l_open” another health. He was a bugler when he w 16 and , and now he's a sergeant and j of him, either. in, I s small for the love of you, relped to make a vou'll be Keep on, my son . , like your old troop in another ye Healy was selzed with an attack of sneezing, so that he buried his fa in his handkerchief. Little Mother 1 t {3 whitened an wrinklec h. i 1 red and oy said the sion. made a good one, ? 1 me much You never t 50, dear,” the laundress answered in p on the door, nd ope peremptory Tot and offi- ing into the room artin ros mpelling g Seddon! ‘hat's up? Come in!” ited and befurred, en- of oversh complime he knows to Mrs. R when stripes The order] the table.and he of the and placed two bottles of wine on t again to resume nis post at the najor commandi Mot Revell’s eyes, and her son “How kind of the a good friend to me. promotion. Martin.” “Ah, | ou he remembers, you think he aches gave him d major!” she said. ‘“He's been » think h e should réemember your mother,” cried Martin. orgets how you nursed him when the 1at bullet in the ribs?” 1th,” Healy muttered, “an’ maybe he moinds fur- back than that, me boy, when he wuz only a sargint hisself in the an’ yer mother nursed more nor him through the buliet fev i “He: !" eried Moth Revell, nervousty. fam.” said the long-legged, red-halred corporal, fther openin’ a bottle of wine?' it shampeen?” cried the farrier, excitedly, “or ybe sherry-wine?” in, av ve pleave,” said Healy, 1 vez. It's naythur. It's port, an 6lC shi »d gintleman's w A thre Revell, me grandfather had dozens uv it in his counthry castle in th’ ould the farrier cried. waving a corkscrew. said the corporal, sudden(y snatching d upon his friend. *In a matter of this koind enough to remimber me rank is huperior to vours.” And he opened the bottle with dignity. They had but once sipped the unwonted liquor, and were beginning to comment upon its taste. when once again there came a rap upon the door. a rap as peremp- tory and official as the first. Fin Straif, fearful of intrus. ively thirsty throats, hid the second bottle promptly. and Mother Revell nearer the stove, away from the draft of the opening door. Again the snow drifted in as Martin Revell answered the knock, and again a snow- bespattered orderly entered. This time it was the orderly * trumpeter from the sergeant major's office. “‘Sorry to disturb you, Mrs. Revell,” he said. “‘Order from the adjutant’s office, sergeant.” “r;“Hanl" shouted the sergeant. reading the order. ming up from Fort Nickerson, Healy. growled the corporal. “It's stony .l am.” Mother, I'm in charge of the escort to meet him at ‘Wolf Creek—start right ay—meet him to-morrow noon. That breaks up our part w!” the farrier cried. ¢ how to run a roster. It's nct your turn.” unior sergeart heads the list,” sald the orderly, ‘Thank you. Mrs. Revell—your health! My worg! You're tony!" “I'll report at the office with my men and the escort The sergeant major don’t GOT into politics naturaily enough and yet accident- ally—at least not purposely. I went into the army in 1862 when but 16 years of age, and before I had completed my education. I served three years until the close of the war, and then at 19 came home from the excitements of the field and resumed my studies. It was a time of great political events. There was im~ tense feeling. Great men were on the stage and great questions were engaging attention. We were working out the settlements of the war. I naturally took inter- est in all that was occurring and thus became familiar with politics befere quitting the academic life. I left school notwithstanding, without any thought of engaging in public affairs. On the contrary, I had a fixed determination to adhere strictly and exclusively to the practice of the law. I got along very well in that profession until General Grant’s second campaign in 1872. I was his great admirer, and could not resist the temptation to take the stump and make answer as best I could to the flerce charges of various kinds that were - made against him. This was the putting of the hand to the plow, and there was no turning back. The demands for campaign work grew with the vears, and before I knew it I was being mentioned favorably in connection with official position, and fin- ally in April, 1879, I had my first personal political suc- cess in the shape of an election to the office of Judge of the Superior Court of Cincinnati. Alter three years of agreeable official life T became ill, and on that account resigned. I quickly regained my health, however, and once more engaged in the practice of law. I had no thought of returning to pub- lle life. I was therefore surprised as well as gratified when the following year, 1883, 1 was nominated for Gov- ernor without opposition and by acclamation. Since then I have had a very active and at times rather tempestuous experience. i e TSR N Sindzihyy s | S &= - MOTHER REVELL RUSHED TO HER SON AND FLUNG HERSELF ENTREATINGLY ON HIS BREAST, BUT NOT BEFORE Hig REVOLVER HAD CRACKED. wagon in half an hour,” said the sergeant. “Good-night, mother!"” “It's a bitter cold night for escort duty,” said Mother Revell, anxiously. “Wear all your furs, Martin, and take as many blankets as you can manage for camp. Walit, I'll fill a flask of the major's port.” “‘She knows it all,” Fin Strait murmured admiringly, toasting his toes at the stove. ‘‘She’s an old warhorse, is your mother, Martin. Goodby! We'll finish the wine drinkin’ good luck to you."” Mother Revell let her tall boy out, kissing him good- night, and returned with a shiver to the fire. “Mam,” said the farrier, softly. “I beg your pardon for that s about his father. : 1 Iur%o 3 “Hush!"” said Mother Revell, paling. ‘“There's only you and Healy and the major left that knows the truth of it. The boy need never know. Come, you've all given toasts but me. Here's mine. The new sergeant! May he never know trouble.” There was a tear in her eye as she sipped the wine, The harness of the six-mule team shook merrily in the moonlight, but the wheels of the escort wagon were al- ss in the deep snow. The wind tossed up through which the mules plunged with snort- ing breath—breath that passed out on the freezing air in white clouds. Round and round, all about, west where the foothills cuddled close to the mountains, nortn, east and south, there was nothing to be seen but the soft, white moonlight, falling upon the bolder white of the flat and snowy plains. The escort, not yet appeased at their fortune in being turned out for such duty on so vold a night, growled within the canvas covering of the wagon or tried to sleep. The night passed thus monotonously, and it was nearly dawn when the junior sergeant awoko and was softly called by the teamster in front. They were fording an icy stream at a bend, where the creek split and broke about a wooded island, a bushy strip of land some twenty yards broad. The gray-beardeda citizen driver jerked his fur hat toward the isle. D'ye mind, Martin, when you w a kid at the post school, and the paym er's clerk was brought in dead and the money gone? ’'Twas there they done it—Wild Horse Bend. “I remember something of it,” Martin answered, “ten or twelve years back. One of them was shot. There's never been any trouble up here since, has there?” sald the teamster, yawning. day they made camp and rested their mules at k; lighted a roaring fire and ate steaks from an antelope a lucky shot had gathered in. At noon there dashed up, with a clatter of harness and a cléud of crisp snow, the paymaster’s ambulance, and, behind it, the escort from Fort Nickerson. The impatient officer, anx- fous to get on, announced his intention of resting just long enmlih to feed and refresh his team and then riding through the night, and paying off next day. Once more the escort climbed into their wagon, shortly before sunset, but now they had to dispense with the can- vas shelter and keep broadly awake, following closely the paymaster's lighter ambulance, precious with the treas- ure of two months’ pay for 400 men. The moonlight was gone; gray clouds had sullenly been driven up by the scourging wind. The snow drifted so thickly that the air looked as in a snowstorm. By 10 at night, when they came to Wild Horse Bend. the teamsters weére pressing forward their teams and thinking of blizzards. The es- cort was fifty vards behind, when the ambulance mules slowed down and began to ford the stream at the island, The soldiers’ sore eyes were weary, facing the wind and piercing darkness, and the teamster was too cold to swear much as he urged his wagon after the lighter vehicle. They were but a few yards behind. when from the bushes of the isle sounded the quick crack of a rifle and the am- bulance driver gave first a cry of pain and then a tempest of curses. The echo of the first shot still sang in the wood, when “bing, blng!" replied the revolyers of ‘the ready paymaster and his clerk. Somebody’ shouted a command, and four dark forms leaped from the brush. ‘“‘Hands up! Grab that bag, Jack, on the front seat! Hands up, d—n you! Quick!"” Drop that bag!” cried the paymaster. “Sergeant!” And then came a dreadful scream as a pistol cracked at his eye and he fell back dead. The soldiers were out of the wagon, plunging through the drifts. and even as the paymaster fell Sergeant Revell discharged his carbine and dashed to the rescue, followed by the men. At the ambulance the clerk was fighting furiously; the precious bag he had thrown between his feet. Then the soldiers were upon them and it was all over. The robbers had not been quick enough in their daring dash. The man at the heads of the plunging mules slipped off first, and the other three dashed across the half-frozen water at the sight of the blue and belted over- coats. The squad fired a volley after them, futile in the storm and darkness, but Sergeant Revell suddenly darted from the others. plunging kneedeep into the creek. One of the outlaws had slipped and stumbled in the stream. In a breath the agile lad was on top of him. and strug- gling, choking, half-drowned, but clinging like bulldogs. the two men rolled over the pebbly bottom. Martin held fast, and quickly others came to his assistance with ropes. In a few minutes the prisoner, bound cruelly tight, lay at the bottom of the wagon, a mat for the soldiers’ feet, and the teams were away at a swirt trot for the post, the pay chest safe, but the paymaster murdered. po sy Mother Revell, old cam{ml er and fearless of weath- ers, pulled on a warmly lined pair of rubber boots that showed honestly beneath her sensibly short skirts, wrap- C000000000000000000C000000000000 000000 .ped a warm shawl over her head and shoulders ar¥l ven- tured boldly away from her little cottage by the creek, plodding through the knee-deep snow. The blizzard which the teamster had scented afar had biown past, and ag: the wind was stilled, so that the drifts lay motionless, freezing crisply in the moonless night. Number One on the guardhouse porch, beyond the lines of barracks and officers’ houses, lonely in its grimne aw her coming, a cloth-covered basket on her arm, and challenged her with smiling ceremon; “Who comes there?” he cried, and she answered cheerily, “A friend. “You bet you are, Mother R said the sentry, and helped her onto the porch. Want to see the ser- geant?” He opened the guardroom door and pushed her gently n. “Another prisoner for you, sergeant,” heé sald, and grinned. “Holloa, mother!” cried the sergeant coming forward from his little office bedroom. brings you out in the snow “It’s Mother Revell!” the troopers called out, throw- ing aside cards and jumping from their bunks, “and a basket. What's in the basket?” “I thought.” said the little gentle-eyed woman, twho, for all her long, rough life with the army, could yet blush pleasantly. “I thought as it was Martin’s first guard &s a sergeant, you boys wouldn’t mind if I just fixed you ail a lunch, ‘seeing it's so cold.” The sergeant laughed and gave the little woman a boy's hard squeeze. “You ought to be brevetted colonel!” young trumbveter. “Ach! Mutter Revelll Why vas you not secretary of a_ Dutchman grunted. ked his head in at the door anxiously. :p some for me, Mrs. Revell,” he cried, f an hour yet to freeze out her pies and a can of better tha: messroom from the big basket, and thessoldiers ate with ous good humor. M 11 sat on the edge of a and eyed them . She knew them all, : f their s as she had known recruit and an, private and sergeant of the ok troop for twenty years and more. Her quick gray eyes glanced from one 10 the other motherly. “Brown,” she said, “is them your best boots? Mind you draw a new pair next clothing issue. You'll be on the sick report with pneumonia If vou dom't take care. Billy McNab, how's your arm? Thought you knew better than let vour horse Have you got enough coffee? Martin, b . mother Mrs. Revell glanced at the barred and closed door of the common prison room. “Mayn't_they have some, poor things?" “Oh, we're empty to-night, mother. There's only old Barney’ Constable—the usual thing—and he's sleeping it o2 of the guard, “What screeched the earnestly. Hot mince pie coffee cam throw you. “Poor old Barney! I doubt but they'll bobtail him in the end. Where's the—the stage robber?” she whispered. “Sulking in his there. I guess they'll ship him off to the civil authorities soon if the rpads open up. If it ard they'd have sent him before ve days now, and the adjutant v of keeping such a desperate en shack.” Mother Revell had a littie of a woman's curiosity and a great deal of a woman's tenderness. “He must be cold in that dark cell”’ she murmured. “Won’'t you give him a mug of hot coffee?” “He'd only growl and refuse it.” “Let me,” said Mother Revell, with innate Red Cross proclivitie: She took the tin cup and filled it steaming full, and took as well a piece of pie. With these she stépped lightly along the dark corridor to the rurthest cell, a dark and chilly dungeon, utterly lonesome, securely barred. She used timidly a foot away from the grating. By the smo light of the oil lamp in the corridor she it to see a bundle of blankets in the far corner. uld you like a cup of coffee and a piece of hot e?” asked Mother Revell. The blanket was slipped from a shaggy, gray-haired, earded head, and two eyes, redshot, stared out. “I've brought you a cup—'" The blankets were tossed aside, and the prisoner made a spring at the bars. His lips were apart in surprise; his hands shook: his eves were eager. “((i}oodf Lord! Are you still with the boys?" he whis- pered. & The mug of coffee shook in Mother Revell’s hand until much of the draft was spilled on the worn-out boards, but Mother Revell had courage and wit and presence of mind, developed by her unusual training. She neither scrp;‘amed nor fq!nted. but her breath came pantingly. You again!” she whispered at last, and they iwere silent, staring at each other, the man with an astonished, hnlg-}fleased smile, the woman white and dazed. At last :gs b:\:gd herself and pushed the coffee and ple between ;’{Dflnlg]{{té"tsh% m\lrn&uredA *T shall see e nodded to her an > t“"}i“hfi plel.z gulped the hot d other Revell had heen gone but two she cr)alr‘x;e(gafkbtn the guardrzom. minytes whon X at brute fright P g are white as your a P et St s pron. ‘Hush, Martin,” said’ the old lady with a shiver. hadn’t been for the bliz: We've had him this. pi ou again.” nk down and “Don’t call him that. It was only that lonely-cell that frightened-me." “Ha, ha!” the troopers laughed. ‘A veteran of the war frightened by the dark! Oh, Mother Revell!” The delicate flush, so readily provoked on Mrs. Rev- ell's cheek, saved her pallor from being again noticed. ‘‘Has the major seen him?” she asked quietly of her “No, only_the adjutant, but the fellow's cute. He won't talk. Nobody is allowed to see him. Angels of mercy are, of coursé, excepted.” He patted his mother's cheek, and she tried to laugh, then took her basket and bade them all goodnight an quiet guard. She walked steadily home, tramping brave- Iy through the drifts, answering cheerily enough . the greetings of a party of officers she met as they came.out of the club, but, once home, she lockea and barred ihe door, put out the light, and sat, her face hidden in her hands. until morning, by the stove. Before the bugles sounded reveille round the white counterpaned parade ground she was up and busy. poking into odd corners for something she frowningly sought. At last she found it, a little steel tool, and she slipped it in the bosom of her dr She fed the stove und made cof- fee again and filled her can. Then, while the dawn hung rously in doubt, and the sky in the east was slowly bling from violet to gray, she pulled on her boots and took her shawl, and once more started for the guard- .. There the men were weary, and.those not out on re sleeping. The young sergeant was wrapped in sound and snoring, and a_drowsy corporal charge. He brightened at sight of Mother Revell's the dark and cold of son. egum, but e the sergeant with yer cod- dlin’!” he said. *“S! 1 wake him?"” Mother Revell shook her head, and poured out a mug- ful for the gratefu s he asleep?’ d, nodding toward the priss “Just now he was swearin’ at the cold.” “Noj e 43 horribly cold in there,” she said. “Won't you give him a cup “Shucks, Mrs. Revell, ye're all "Twas him killed the pavmaste: “That's not certain yet,” said Mother Revell, sudden- 1y shaking. “But it would be cold for a dog in there. Let T heart. The corporal shrugged his shoulders. It was nard to refuse Mother Revell anything. So.again she slipped along the corridor. The prisoner must have heard her voice. for he was already at the bars. “Bessie,” he hoarsely whispered. ‘Youw’re the same as good old girl. And you haven't forgotten the old A corner of your heart for him still, en?"” She shrunk from his bloated face for a moment, the next she stepped determinedly to the grating. : ten,) she murmured hurriedly. “Don't touch my hand. I'm going to help vou, but not for your sake—for the same reason I helped you before, when, in your drink- ing craze, you shot the cowboy in Dodge. I wanted to save my boy the shame of hearing his father was hanged. I want to save him again. “Little Martin—the bz see him—Be! % “Never, to be p Let me Bessie, is he here? e cried fiercely. “He's doing well, he's a d of. He studies and will pass for a com- mission in time. He knows nothing of your life. of you, and never shall. T'd die first. Do vou think I'd see the boy creep about in shame for his father, a deserter, twice a murderer? Could he hold up his head among his com- rades when he's an officer and a gentlem he will be, as he deserv to be? See you! Neve You must go away—escape, else there are some here -will recognize you. She wa coffee sulkily. his stove. 5 “What name have yvou gone by? You dare not call yourself R 117" “Hardl; he grinned. “Take this.” she said..and gave him the tool from her dress. “It's all T could find—a gimlet. You bore hole af- ter hole in the planking of the floor. until a piece is loose. Tt's slow and you must be cautious of the guard seeing vou. Get through by night after next if you can, for they are eager to send you to prison. There's a foot and a half between floor and ground. You can crawl out. Tt was done once by a man at Fort McKinney. Look out for Number One. He passes around the guardhouse every quarter of an hour.” He took the tool eagerly and she turned away. “‘Bessie!" She paused. “T saw in a paper that Pollock was made a major. He always had luck. You and T remember him as a big buck private when I was a sergeant in the war. Say, Is he—is he stuck on you still? T cut him out for fair then, didn’ 1? T half thought you'd get a divorce ana marry him.” She looked at him flercely. “The major’s a good man, not fit for you to name. Get away from here as quick as you can, and remember this-- ther: only one thing I love in the world, and that's the boy. “She slipped quickly from him and through the guard- room, past the drowsy corporal and regained her home before the sun was yet ahove the plain's far rim. 11T The young sergeant came to his mother’s little break- fast table in poor humor. o ' “Mother, can you give me something to eat?’ he cried. “They’ve detailed & new cook, and he can't either bake beans or make coffee. The mess breakfast was ruined. This is something like. Nobody, alive or dead, ever made hash like you, mother, and this is coffee, not bootleg. Say, mother, you're pale. What have you been doing to your- self?"’ “I?" she answered, and the soft, sweet pink spread on her cheek. “I'm all right, Martin. Are you off duty to- day?” He shook his head. “No such luck. Guard,” he answered, and bent hun- grily over his plate. Mother Revell paled again and trembled. “Guard!” she said at last. “Why, Martin, you were on the night before last.” 5 z “Can’t help it. Scheidermann’s gone sick; Foley's act- ing sergeant major; McMillan'’s on detached service, trembling now, and he gulped the steaming The men snored; the corperal nodded over "JOOOOOOOODOOQOOOOOQQ 00‘0000000_0000’3000000 HOW TO SUCCEED IN POLITICS BY SENATOR JOSEPH B. FORAKER OF OHIO. i telegraph wires; Fairleigh's provost sergeant, :;,eéxd!ggon‘ ’.flwge's only Bob Otis amf 1 for duty—one in.” e ** she cried, jumping up in a passion of ‘hYou car;l't;’you must not!” 3 ‘Why, mother?” % You},' 'you—TI'll go and speak to the Major! What on earth! Mother, you know such things often happen. It's all in the five years. Don't get excited. “You—you'll be ill,” she began to cry. “Ill tire you said, stepping to her side and petting her, “you are ill. Why, You, of all people, know one night in is no hardship. It won't last. Look here, I'm going to ask the hospital steward!to send you dowa a tonic, and don’t you move from your. stove to-day. T'll run up and see you at dinner time. Now, I must hurry and clean my belts = bit.” He left her shaking silently, but turned at the open 00 r. 3 “That hangdog roadagent is to be serit to the railway to-morrow. The sheriff will take charge vf him there. Mother Revell huddled up in her chair as the door closed behind her and became a nervous bundle of anx- jous fears. “To-night,” she muttered. ‘‘He must escape to-night. And Martin on guard! If he should fail, if the guard shoots him—a son shoot his father down! O! O! And if he succeeds, Martin will be tried for allowing the escape, for neglect of duty and be reduced! It will ruin his chance of promotion. O! O!" She sat stunned until the bugles on the parade ground announced guard mount. She stole to the window, and watched. Crash went the band; all the familiar, surrmg' maneuvers were performed in the bright wincer sun. The band ceased; the adjutant and sergeant major saluted: the shrill bugles advanced, and the new guard marched off to the guardroom, the tall and bright-eved young ser- geant in command. She could hear his clear voice even when he was out of sight at the distant guardhouse— “New guard! Present arms!” Evening stable call and the troopers in white stable dress, trotting at double time through tne frosty air of the falling day—supper call—retreat and the sunset gun. Martin ran in to see her and found her so white ne re- solved to brinf the post surgeon in the morning. Dark- ness, but she lighted no lamp, and at last came tattoo and taps to usher in a windy night, with white clouds swiftly crossing the half moon.” Night—the final click of the bil- liard balls in the club, the final song at Captain West's evening party, the first silent round of the officer of the 'he sentry at the guardhouse lifted up his voice: amber One, 12 o'clock!” and from the corral, from the cavalry stables, from the haystacks and from the dIsuli.nfi sawmill came the swift replies of lonely sentinels—"12 o'clock and all's well!” Mother Revell rose up, unable to wait longer to bear the suspense. She stole from the house. Well she knew the old post and how_to hide in the shadows and how to avoid the sentries. Unseen, filled with a shuddering dis- gust with herself at having so to hide, she gained the rear of the guardhouse. There, there stood a little clump of scrub oaks by a spring of clear water, and In their shadows the little woman crouched and watched. Tramp, tramp, tramp, to the end of the porch; o the rear, march! and tramr. tramp, tramp to the other end; shift carbine to the other shoulder, and it's time to pa- trol round the guardhouse. So went Numpver One, monot- onously, distractingly. Once, twice, thrice and four times he passed round the building, and it was 1 o’clock. Again he sang the hour, and again came back the distant echo- ing sentries’ calls, “All's well!” Mother Revell was in a fever; she felt no cold; her eyves sought continuously the yawning blackness between the walls of the old guardhouse and the snowy ground. Again the faithful sentry passed around and went back to the porch. A minute passed, and something protruded from beneath the guardhouse, reaching out to the white snow, stealthily, on its belly, like a great, sneaking cat. Mother Revell clasped her hands and shook and watched. Inch by inch he came—the murderer, a big man, while the hole was narrow. The moon glanced upon him and she saw the glitter of his _excited, determined eyes. Inch by inch, without a sound, he dragged himself to_ freedom, and Number One continued to tramp the wooden porch unsuspectingly. The man was out and on his feet, stoop- ing low, glancing here and there to make sure of the right direction to run. g “Quick, guick! Oh, man, be off with you, quick! murmured Mother Revell. As if he heard her he started to run through the deep snow soundlessly. One step he took, and Mother Revell closed her eyes in despair. The man’'s legs. cramped by confinement, were uncertain. His toe struck a rock in the snow, and he fell, noisily bumping against the wooden wall. At that he forget himself, or became at once reck- less, and swore aloud. “Sergeant of the guard!” the sentry shouted, and dashed round the house, while inside tumult and clashing steel resounded. The prisoner picked himself up, but slipped and slid again before he could start afresh, so that Number One, .carbine loaded and cocked, was on his heels. It was no intention of the sentry's to Kkill, but rather to recapture aliv He brought the butt to the front swiftly and thrust viciously to knock his man over like a rabbit. The running blow missed. and in an instant the prisoner turned, a shaggy, wild-eyed image of desper- ation. They closed, but for a second. The next instant the sentry lay on the snow and the prisoner had the car- bine. He was off again with a dash, but now the guard came running out, Sergeant Revell ten paces in advance, revolver at the ready. “Halt, or I fire!” “The prisoner swung about and brought the carbine to his shoulder. A scream came from the spring, and mother Revell ran out. wringing her hands. “No! no! Both of you. Don't shoot!” She rushed to her son and flung herself entreatingly on his breast, but nét before his revolver had cracked. The prisoner was a second later. Unhurt by Martin's pullet, he returned the fire as Mother Revell clasped her boy. Martin heard his mother cry out in pain, and felt her fall heavily forward upon_his resculng arm. The guard rushed past, carbines ready, in pursuit of the fugi- tive,. but the sergeant of the guard paid no attention to them. He picked the little unconscious woman up in his arms and dashed away to the post hospital, terror in his eves. IV out. “Mother,” he “How Is she?" #Is she better?” “Is there any chance for her?" All day long the men came slipping up to the hospital and whispered their anxious inquiries in the attendants’ ears, and went off in gloom when the steward pursed his lips and shook his head. Toward evening she became sensible. and found Mar- tin in the room with the doctor, and a tall mustached fig- ure in the shadows of a corner. “Martin,” she whispered. ““are you hurt, boy?"" “T wish 1 were, dear little mother,” he cried, “so that you were safe.” None of that now, sergeant, or you'll have to " the doctor said. as the lad flung himself on his knees by the bed Mother Revell petted her-boy’ eyes sought the corner. “Is it you. major?’ she asked, softly commanding came silently to her' side 7 “Mother Revell,” he whispered, “don't you wish to speak to me?” She paused. closing her eves, and then opened them upon the doctor. i “I've seen many of the poor boys go, doctor,” she said. “Tell me:” And he told her. The doctor took Martin by the shoul- der and pushed him out before him gently. and the major and Mother Revell were left alone. At once she asked: “He was caught?”’ “He was shot down. dead, Bessie.” «And you recognized him?” “But nobody else, Bessie. Sergeant Revell.” “Thank vou, major,” she sighed. with a content that almost stified her pain. “Martin wiil never know when— When he's an officer and a gentleman. Major, you've been very. very good and kind.” “I'd have done more if you'd let me, Bessie,” he an- . hand weakly, and her and the officer Nobody shall know he was swered. “Do it for Martin,” she pleaded. ‘‘He's not like his father. “No. no, Bess—like vou, dear girl. like vou, Be: She looked at him with a faint shake of the head. ““Bess, give me a right to be a father to the boy. Thrice I've asked you, and you refused, though Revell was good as dead.” “For your sake, major. I'm only a laundress.” “T rose from the ranks.” he replied. “I don’t want to think that the rascal who spoiled vour iife wen to the end. I've been patient. Let me remember you as my wife—take my name.” Arain she motioned ‘“No.” “T've money. Bess, and Martin will he my son—T have influence, and Martin, as my son, wjll draw on it natur- y ““You attack the weaker wing, major,”” she answered, and pressed his hand. He stooped and kissed her and hurried out to send his orderly for the post chaplain. Martin, bew!ldered. was there, and the doctor. and these alcne saw Mother Revell acknowledge the mistake of her hasty girlhood, and mar- ry at last the man who had patiently waited. After that she lay in pain, sinking swiftly, and grew a little delirious. and saw into the future, mpeaking of her boy as “Captain Revell. a gallant officer and sentleman.” At 9 o'clogk she was very weak. but sensible, and sent messages t0 a number of her children—the grief-stricken troovers. Shortly. she whispered to them to open the window, although it was very cold. and they did so. “T want to hear the bugles.” she said. Soon they sounded—the last, last friendly, loving call to rest—taps. (4] be called upon to meet unforeseen exigencies that will turn his career into unexpected direc- ticns, but this much a young man can.always regard as absolutely essential to genuine success in any of the important walks or rela- tions of: life, public or private: he must be a hard worker. No matter what his intellectual endowments may be, investigation and preparation will al- ways be necessary to the satisfactory discharge 000000 0CCO000000000000000000000000000000000000C000000000C0C00000CC000CC00C0000 OOOOP o In my first campaign for Governor the liquor ques- tion was uppermost in the minds of the people, and I was defeated, but two years later, in 1885, 1 was re- nominated and elected. X was re-elected in 1887 and renominated in 1889 for the fourth time and for a third term and again defeated. I was a candidate for United States Senator in 1892, ‘but was defeated by Senatdr Sherman, who received fifty-three votes to my thirty-eight. In 1896 I was elected to the Senate without Republican opposition. I attended the National Republican Conventions of 1884, 1888, 1892 and 1896, each time as a delegate at large * and each time chosen by acclamation. In 1884 and again in 1888 I was chairman of the Ohio delegation, and both times presented the name of Senator Sher- man as Ohio’s candidate for the Presidency. In 1892 and again in 1896 I was chairman of the com- mittee on resolutions, and as such each time reported the national Republican platform to the convention. I also, in 1896, placed President McKinley’s name in nomi- nation. In all these years I have taken an active part on the stump, not only in Ohio, but also in other States. I mention all this because 1 am asked to do so and because it will indicate that I have not only had con- siderable experience, but that it has been of a varied character. While I have had some successes, I haye also had my full share of defeats and disapoint- ments. Some of these defeats have been because of my own faults and mistakes and some of them because of conditions and circumstances beyond my control. De- feats generally hurt a man, especially when attributable to his own mistakes, but they are not insurmountable even in such cases when accepted uncomplainingly and when they do not involve lack of integrity or sincerity. The people do not expect or really -desire perfection, or even a very close approximation to it. I do not know but that they like those who now and then show that they are flesh and blood by ordinary mistakes of judg- ment better than those who never fail to do exactly the right thing. It is the difference between hot blood and cold; impulse and calculation. o Mr. Ford has done a good work by his new book, The True George Washington.” He has brought that great character with all its work and sublimity into closer touch with mankind. He has established a rela- tionship between Washington and the rest of the*hu- man family, whereas according to Weems and most other biographers, there was none, and as a result there is a marked increase of affectionate regard and admira- tion for the father of his country. Since we know that with all his greatness and goodness he yet had many of the shortcomings that afflict other people, we feel / much better acquainted with him, and look upon him as a :i0re agreeable person to meet on the pathway of life. Recurring now to your questions, it is upon this kind of experience that I would advise a young man to con- sider well before he enters politics. Unless he has apti- tude for public affairs ke is not likely to succzed, and if he has power to succeed he must expect all kinds of ups and downs. To-day successful and popular; to-morrow, defeated and censured; sometimes justly, but more fre quently unjustly. To withstand all this he must have good nature and the qualities of self-adaptation. He must learn that his own .. >rsonality is not important to anybody but him- self, 1d consequently the people do not care anything about his grievances. He must keep them to himself. ‘When he meets with disappointment he must accept it as all right and be satisfied to abide by it no matter how permanent its consequences may be. If time should enable him to recover, as it probably will, it will not only be clear gain, but he will be stronger than ever, while if he does not recover he is no worse off be- cause of keeping his temper. I do not think any programme cen be outlined for a young man excepting in the most general way. of public duty. The men who depend upon nat- ural “genius” or upon the “inspiration of the moment” are not safe examples to follow. And not only must he be diligent, but he must be honest and sincere in all he does. Only temporary advantages can be obtained by a sac- rifice of these qualities, and they are never worth what they cost. There is ¢nly one safe rule, and that is to stand at all times for honest conviction without equivocation or dissembling of any kind. His views may be erroneous, or if correct they can- not prevail, but however that may be, a man is strong only when he advocates what he be- lieves. Following these ideas one should attain as high a success as his qualifications may fit him for. Assuming that they are of the best, and that he attains important place and high dis- tinction, are the rewards sufficient to justify the struggles and sacrifices involved? \ The salaries-of public officials are Inconse- quential. They are seldom sufficient to pay ex- penses. The honors are all that is left. Nine times out of ten they are flesting and unsatis- Situations are constantly changing and one is likely to - factory. = 4