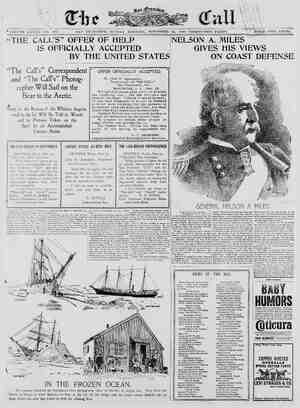

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, November 14, 1897, Page 18

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

S Iked i Thomas Flannelly w om Yorridor. He took a seat where the light from the barred window showed clear and tro He looked at m» idly, uninter- stedly, and 1 looked at nim He sat waiting quite patiently, altogetber in- different. 1 might question it I would. He would answer readily enougzh, if the words came to him, and if my questions bor: not too sirongly upc the very de- of the murder. He had not sought \e interview, but be did not care enough 10 avoid it. He coras very little for anything, this man of 31 who shot bis old father lying of a business quarrel. objected to your having a Iy always speaks of e wanted to double call rent. e as much r body to pay t ez him—to try to make him change his mind ?” He noddec when you came back?” back to the ranca 1 went to 1 you be officers? Had e up mind that you 1ldn’t be tak He looked at e coidest, the s ever met. yes are knew I- wou'd be odd wouldn’t it2” came,’” the question nis story. “I 1 knew they broke aid and was in ey riff McEvoy well?” at ked for 1im election he am said Fla the other a sorry,” leg over the wo mig g out of when e price of mi I couldn’t | SAN FRANCISCO CALL, UNDAY, N (s 18 OVEMBER 14 “That’s natural,’ forg of the officers of the jail at fau Jose. | *“When you go out to take a man like that you must expect such thin But to kill | his own father, a man 65 years oid, lying | in bed—why, I never saw a man like him! | And ne doesn’t seem to care—nota bit.” | || | No, Fiannelly doesn’t care. I he:itated ptau i when I spoke Lis tatber's nime. Butit | was quite unnecessary. There was more | €motion 1n my voice as I questioned him | than in his when he answered. He shows no grief, no remorse, because he feels | none. "The man’s nature is as cold and | as lacking in emotional depth as those | unblinking, clear light gray eyes that meet so incuric His is not the | quiet of despair. Itis the silence of dull, passive stolidity. Flannelly is merely | | waitmg now. He Isn’t thinking. He | never has thought. There isn’t place in that round, b acked head, with those | greav mis-hapen ears Iying flat and close, | for a cont in of tho i—much | less for repentance, for remorse, or even \2iy said one one ous t ‘o, he wasn't frightencd when we | bt bim from Redwood here,’ said bis juler. “He's got nerve—grit.” Then Flannelly’s courage is the courage | | of an unimaginative rudimentary mind. He betrayed no fear of the mob be- cause that tremendous expression | | of the people’s horror of the parri- cide could not' appsal to a nature 50 cold, so simply se.fish, so animal-like 111s qu ek 2imost passionless revenge, Flanneily cannot suffer mentally. He 1s | as lacking in self-criticism, in even the | | faintest analysis of motives, as though there were some phvsical omission in the make-up of his brain. And he is asinsen- | sitive physically. While the surgeons | probed and a:it-nded to bis wounds he ! smoked his pipe in stoical silence. He ! didn’t wince. He took no anesthetic, merely because he has all the degenerate’s lack of sensibility. didn’t feel the n, he told me, quite simp! TR This man doesn’t brag. He has no pose. His is too uncemplicated & nature to be seli-consciot His manner while | we sat and talked was quiei, with no pre- Not that | not that he resented my | ly that nature has not e ed this ne of her creatures w those intellectual tentacles which reach | out for knowledge of other tentacled be- tense of courtesy or cordiality. sulile was tio he do One cannot jeel sympathy for this man. | 1 I never thought iman being, real give his 1 blood he has shed, that last qu rai in the t ire here— to the worla. some strong qualit con'd look upon a he must per- bution for the o s not kin behind One look out upon the world from ndy lashes. THOMAS FLANN o5 feeling to is not de- soded. Do you get | fiant, not crushed, held in the |anszry quickl k secking some 2 ows strong | excu-e deed. er Iknow t i i 1o some i g long to get angry.”” natures to conceal depthsof suffering fro “You were angry that night?” tive eyes. Oane respects “Wkten I rode in town?"’ 150 faras I can ju fe e behind F.annelly’s crude, I was a little excited te men, rded sentenc saye the de ot to ! after I left Redwood."” 0 condemn the | injure his case. And his capacity for su: “A httle 1 bav, turns on his g is as deep as the sentiment in those | And you kuew that your father was for life or freedom. lodc, distrustful, steady, small eyes, that | dead ?” ) | < P = = < = ¥ 5 & LS LA RSt Wiy HL LAY /Ks/ .»g/ > N SAPATAIA, ;]/ b /4\// | & — ( ool of Mechanical school is pt Its The industrial in- cours ntoa boy in order that s of observation may be awak- g t ngthened and his 1l developed. The student demic instruction also. ol here,” said Mr. Merrill, *is ly a trade school, and in such a ndustrial education is itself the t. Its pupils are tauzht to earn living. But the New York trade )C make the mistake of taking and handling them just as i bedone in a shop. They follow closely the old apprentice sys accomplish greater ons. The object of to turn out more lents m. is not a trade school workmen, but better. “It has in reality three functions, | theuch the general outsider does not see than one point of view at a time. | ust benefit the in- dividual by gi m the best possible cquipment for his life work. must be suited to the local needs of the commun and better them, tending often to im- prove an old trade or create a new one. Third, the first two functions of the school having been fulfilled it necessarily foilows that the last will be carried out in the benefit to humanity in general. It is the development of skill in trade «chools that has given Germany the lead in tie manufacture of fabrics, weavins erc., and caused it to take away much de from England in these lines. Trade hools were in existence manual ining schools, for the reason did not undertake to do an 1 is done for apprentices in the with the added wisdom gleaned schools the California Arts, though but years, has raised tbe standard in indus trial educaiion, aiming to turn out a few students at each graduation who will go into the shops and become superior work- men and citizens. ‘It is the first time,”’ continued Mr. Merrill, “that any school has tried to combine manual training with training in the industrial arts. But these two ideas are really supplementary to an extent which an outsider cannot comprehend. “And so,” concluded the principal, “this school has been successful for the very reason that it has had a high aim irom the beginning, and vet has always met different conditions as figured out be- forehand and proved later.” The Lick School, founded through the wenerosity of James Lick, contains this year, 220 boys and 80 girls. This number is limited on account of the present ac- commodations, which the school is fas outgrowing. Forty counties of this State e represented in the attendance, and no students from other States are admitted except those born in California. On en- trance, all the students are on the same foouing, each going through a two-year from School of Mechan- in existence three r Merrill, princi- | preliminary course, which is substantiall it will elevate | long before | the failure of tbe Eastern | HUY (s {@\g Fagevia 3.113@1&*9. 1 But even if the country boy ays only two years in the <chool, he is | the general course in tool wor -called | z the time ven in chools, dividi, same as that t b e manual training equally between academic and industrial fore the younger city boys are | branches. The former iucludes English, | given a good foundation training and are thematics, history—in fact, | encouraged to remain longer in the school. a general hig hc >urse, with Herein lies the very weakness of these emphasis on the sci nd math | ols—they do not give the in- In the industrial b hes of this pre- | dusirial foundation., But we are nearer liminary course the pupil takes the ele- | the German idea of a irade school. work, During the iirst year every boy spends an hour and a half daily in working department, where he learns the use of tools and makes simple studies ot joints, dove-tail mortises, ete. Later, as a young apprent ne makes drawers, cabinets, benches and drawing desks, and besides these, Mr. Merriil exhibited with just pride certain woodwork, both useful | and ornamental, about the buildings m s of tool making, forgi nd practice in the mach op. There are also the in- custrial art branches, including ireehand and mechanical drawing, modeling and wood-carving. In place of the tool w the girls take domestic subjects such plain sewing, dressmaking, millinery, cooking, sanitation and household art and science in general. pattern- arpentiy, i {end o tha wood- | | Y N answered, with un- “Yes, I knew he t the officers to follow frer—afterward ?’ “Didn’t you e tto the I didu’t exp w did 1ink as you rode You kno a child dreads ment after lie has done wrong.” ily looked uninterested. e cia not answer. “Nothing,” he answered. It is quite possible to imag: thinking nothing. the zirls in their own department proved fully as intarestin In the sewingroom, which wus un Miss Crittenden’s able management, the long tables were neatly kept, and each irl was provided with a pretty littie s ing-basket, tiel with blue ribbons. Dur- ing the first year the giris are zed on picce-work, draftine and cutting patterns | accorhne to the McDowell system, and the planning of white garments. At the the second year a woolen dress is During the third r the girls the designing and fitting of toys, the work of er finish take np dresses and make a wrapper or iea-gown at the close. The fourth year embraces the making and finishingof tailor-dresses, jackets, etc. Sometimes the girls work on orders which tbhey bring in from out- side persons. One young girl made a very pretty waist and sold it to a companion for §3. Another girl in the third year | class made a wedding dress for a friend. In the cooking-school a doz'n girls tted about the room 1n dainty caps and h white apre One et was making and some cornstarch. An engaged mixing dough for soda-biscuu's, while a third learnel.how to steam rice. Atone side « om was a large cook- | ing range, sn of the six tab esin the center tal its own tiny ges stove. Here | also was used the Aladdin oven, with its double wals lined with asbestos. All 4 ‘ | | | { IN THE COOKING SCHOOL. After passing through the prescribsd | which his boys had made, The forge- elementary course each student selects | presented a busy scene with one of the thirteen different trades taught l | | apprenticeship. = A premiam is put upon | welded rings or tempered steel. | good work, and th:re is no stated time of | In the machine-shop, the students were graduation, now engaged in the manufacture and This course of study in the school is | polishing of whesls tor engines and arranged to meet, as far as possible, the | dynamos, baving just compleied a large varying age ot the students, which forms | number of sets of tools for an industrial | & large factor in the problem. For in- |school in Nevada, Near this shop stood | stance, the average age at entrance of the |-another building containing a large brick city boys is between 16 and 17 years; of | kiln, whe“e the students iearn how to the rnral boys, over 17, and the latter are | bake their own clay modeling. not as lixely to remain all through the | Althoughsolargely outnumbered by the Toom | about the room were charts displaying the the sparks | differex fiying in all directions as the boys in caps | Out and then sp2nds two years more in formal | and overalls hammered out iron bolts, | girls are | | l cuts of limb, beet and pork. all the cooks each week certain | chicsa2n 1o Gothe marketing, whila, three of the class act as housekeepers to attend o 1he dish-washing, stove-cleaning and general dus! * P In 1884 the Polytechnic High School or- zanized as an offshoot of the Boys' High School. A vear's commercial course was then given in the present Normal School building on Powell stree, and the boys went there from the High 8chool to stu bookkeeping, shorthand, business arith- | daily papers. Of thisyear’s pupils George | Judging by the present appearance andi )&WWMM i cared to tell me. | trades or office work in | hopes | vanced course in the construction of elec- HIS = GEEL} “*And you went to bed?” He nodded shortly. ¢ d to sleep?'” “The same as usunal.”” Aud two miles away old Patrick Flan- nelly lay dead ! O course one hesitates to believe even a Thomas Flann so little affected by committing murder, and the murder of his own r, 45 10 be able to fall asleep ‘“the same as usval’’ that night. It is to | be hoped, for Fiannelly’s sake, that he has a better story to tell a jury than he For it takes more of an excuse for Kkilling one’s father. He has acknowledeed in other interviews that he knew the officers and spoke 1o them be- fore firing. I trust Flannelly is not rely- ing npon suen flimsy falsehoods to make his fight for life. - w Once when I questioned hiim too closely about the events ¢f tbe night of October 26 Flannelly said: *Now, 1 think you're askin’ too much.” But Le was not in the least restless. There isn’t a nerve in this man's body. His attitude is reposeful, easy, ard he changes it seldom. His hands, strong, hairy, with their short nails, lay crossed in his lap. They show the effect ot seven years’ work on the Fair Ocksranch. He touched his snort, licht mustache occa- sionally and rubbed his small, weak chin. His voice never faltered, his eyes nev fell. Hespoke of his youngest sister as his favorite, but with no more emotion than when he mentioned his mother or father. The degree of affection Thomus Fiannelly has to testow upon h's favorite si. serve as & measure of the kindly f that stirs that cold heart for the rest the world. *‘She knows—of your trouble?"’ ‘“Yes. She must know it now. They must have sent her word from home. She’s at the convent.” “You haven’t seen her since?”’ *Noj; she can’t come out.” “Have you written—can you write ?’ “Yes, I can write, if I want to.” ¢1 mean is the wound in your arm not too painful 2" #*No. Idon’tfeel thei.” =5 e * of * 1t is interesting to hear Flannelly’s esti- mate of his father. **We had trouble some months before. Then when I went to the house—I used to deliver milk there every day—he'd never care to see me unless it was to seold.” “But after that, again?” *Ob, he was always cross — always cranky. He was pretty close, too. When | I or the others wanted anything we'd go to maw. He was always cranky.” There is no resertment in Flannelly’s | voice. He seems 10 bear no ill-will to the | dead man; and tbere is no tenderness | when he speaks of “maw.” ~When will the trial be?” I asked Flan- nelly. ““When they get ready, I suppose.” *You would wish it soon ?” It can’t be no sooner ’'n when they get ready,”’ he answered. He hasn’t thought about He doesn’t care. He cares for nothiugp. When I thanked him for the Flannelly didn’t answer: not because he weren't you iriends the matter. whether 1 thanked him or not. When | the juiler brought him a glass of whisky— for Flannelly is not yet so sirong that he | can sit up for any length of time without | becoming tired—he empti=d the glass and returned it without even a nod of thanks, | Ceremonies—even the most rudimen: | ary—are not in Flannelly’s line. When I | said good-by he didn’t. He looked at me he passed out into the corrigdor—the slighter, <horter jailer with an arm half | assisting, half guarding, about his shoul- | der —as he will look at the people { who will crowd the courtroom at his trial ‘| had sent her a message, she interview | was surly, simply because he didn’t care | and as he will look when he sees for the last time human faces upturned in puz- zled, cutious, shuddering questioning— cold, unintercsiine, unmoved. s SOl SR Thomas Flannelly’s mother sits in het/\ orderly litile parlor, whose blinds are de- cently closed. She is dressed in black and she rocks gently to and fro as she sits, her wri:nkled hands folded in her lap. Opposite to her sits a Catholic priest, and I envy him his power to comfort Patrick Flannelly’s widow. For 1t is not from his mother that Thomas Fiannelly inherits that surpris- ing insensibility. is woman is suifer- ing. Like herson—like most uncultivated natures—she has that sirong reticence | which makes speech, when it describes | emotion, an effort. Mother and son look alike—the same small eyes, though hers are dimmed and dulled and softened by age and suffering, and the same peculiar narrowness across the ey But in the mother’s sirong, homely face, with 1its reddish hair, which grows gray slowly, there is all that is lacking in Thomas flannelly’s, the humanizing touch that makes the witnessing of her sorrow very painfal. When I told Mrs. Flannelly that I had seen her son taat morning, and that he t quite still for some minutes. Her poor, old face worked pitifully, and finally she asked in a voice har!ly audible: *What is i1?"” *‘He said to tell you that he is siting up, that he is getting better and that he feels pretty well.”’ It wasn’t much of a message, and ¢ remembered the toneless, indifferent voic in which it* had been spoken it seemed | hardly worth while. ‘When [ offered to deliver a messagce to his mother Flannelly hesitated, partly through distrust, I syppose, but chiefly ‘because he lacked words, it seems to me. He was like a ciiild, ignorant of the form in which the thought shouid be cast. “Your son told me that he was your favorite, Mrs. Flannelly,” I said. “Well, he’s not now.” There was anger in the tone and griet ard acute suffering. “‘He said that his father had been harsh | with him.” | *“Well, he was not. His father wanted rent from strangers, not from his own son.” She sat thinking for a time, and then she sdded slowly: “But he was a good boy—a good child until he got in with those Doyles.” Poor M F¥lannelly! Poor widow, | whose husband was killed by ber own H her faverite son. Themas Flanneliy’s mother—it seemed | to me when first I spoke to her—had cast him off. 13ut back of the anger that makes ber rough voice vibrate, behind the hor- | rible complication that it is her husband 1[ whom this man has killed, 18 the fact | tbat, after all, this is her son, her boy. | See, she is already making excuses for | him. Before her neart has been eased in the slightest this sorrowing Irish mother | of thirteen children is saying that of her | wayward boy which mothers have said since there were two boys in the world to | play together—it is some other boy who | has spoiled hers. Her own boy was nat- | uraily a good son, a good child. MirraM MICHELSON. metic and commercial law. As the school rapidly increased in num- bers it finally moved to its present site on the corner of Bush and Stockton streets, where a new building was added three vears ago. 7Jo-day the school contains 76 pupils, ana is redited to the Col- esin Engineering at Berkeley. the educational side is particularly em- i On acconnt of the exceedingly cramped accommodations such a plan of study as foliowed in the Lick School can- not be carried out. The subjects oifered during the three- year course in the Polytechnic High School are classified under two heads The commercial course, for pupils desir- ing a strictly commercial training; sec- zed. | ond, the general course, intended for pu- pils who may wish a commercial training ) but desire more latitude in the selection of study than the commercial course | offers; also for pupils premaring them- sel s for other schools, for tho different architecture or engineering. In this course are the sub- ts embraced in manual training, a shop work, drawing, etc., and the a demic studies related to them. All t does not include the night school, whose principal is Mr. Kirkpatrick. There are 700 puplis attending st night and taking a commercial course, with incidental work in instrumental drawing. Small wonder tkat when the Grand Jury visited the school two weeks a;0 they pronounced the accommodations out of all proportion to the number of students attending. [n the elementary drawing class the pupls were making pen-and-ink sketches with rafererce to industrial work, such as illustrating, enlarging pictures and in- terior design Bach student 1in. the manual trainicg depirtment here con- | ceives and draws the aesign of some pro- ject that he will tinally complete in his | senior year down in the carpenter and machine shops. Along with this ele- mentary drawing he takes a course in the wood-working shops, where he learns the construction of various kinds of joints. After this he makes drawings of vurious vatterns, which he turns outon the iathes. Later still, he learns how to cast his de- | signs, for arrangements have just been | completed with the firm of Garratt & Co. | whereby the b | taken on one afi of the school will be rnoon of each month to iheir casting wo! In the junior year the boys begin with forging, and in the second year take work | in the machine-sbop, togetLer with lec- tures on the practical menufacture of iron and steel, the strength of these, and | also study the eonsiruc ion of steam en- gines, pumps, valves, etc. The third year is chietiy devoted to the study of electricity and electrical coustruc- tion. The instructor, Mr. Carniglia, in ancther year to start an ad. trical dynamos, motors, etc. Alreedy one of the nighest students in the senior class, Sidney Phillips, has con- structed by his own efforts a switchboard and various meters, a gas engine and an electric dynamo. In the manual-training course the girls study free-hand drawing, pen-and-ink sketches, wood-carving and modeling. The last two are taken by those inteading to make a specialty of iuterior decoration and a study of ornamental desizn of a historical nature. Besides these a few girls in the machinesshop were engaged in making fancy screens and frills of aelicate Venetian iron work. The work in the art department, which isin charge of Miss Van Vleck, is espe- cially interesting. OF last year's class of rising young artists M. Igoe, Tom Dorgan and Miss Elsie Hinrici are doing work for Here | Magee, George Steele, Anna Gorham and Belle Mclvig all took prizes offered for posters. Six other students have already sentin posters to compete for the prize to be given by a soan company. Miss Jane Marvi calendar in black and white, and is now engaged in making two calen: ning Chinese babies. and-ink sketches in paper. Miss Marvin has sold | these calendars. As for Miss Garham and Miss White they will be busy clear till | Christmas filling their orders for menu cards. 1n this art department all the oneyear's instruction in modeling before they take up wood carving and free-hand drawing is taken throughout the three years’ course. The giris in the wood- carving class were engaged in making There will be pen- | 1 | from their own designs grills for win- |dows and doors, fancy chairs, and | tabourettes. Two of the students, Miss | Flint and Miss Morse, are making grand- fathers’ clocks. One girl is making a Renaissance chair ornamented with elab- | orate dragons, another has almost fin- | ished a piano-bench highly caryed, and a third is carryinz out a curious desizn of | her own—a snake of white holly wood set | in a piece of ebony, the whole to forma panel of acabinet of holly. PREHISTORIC CITY [Continued fiom Pege Seventeen.] the crudest description. Those found on | Black Mountain were a little cruder than | those that have been found in Arizona. ! They did not know how .to hew stone, | but made the walls of their houses sim- ply by piling up the rough volcanic | | rocls. | Taking these factsinto consideration, | there seems a_po: ‘resiJen‘.s of Black Mountain belonged to the paleolithic period of the stone age. Certain it is they are below those that have been accepted as belonging to the neolithic period. Here is another impor- tant sci=ntific fact, as it has always been a matter of doubt as to whether man ex- isted on the North American oontinent during the palsolitaic p:riod of the stone age. But only long and careful study can set these vexed questions at rest, One of the most important features of the Black Mountain <city is the fact that the houses are in a more perfect condition than any that have heretofore been found. While a number are merely piles of rock, there are others which could be put back into their original condition in a few hours. One on the peak is almost good | enough to move into, if ithad a roof. In the debris of the Arizona ruins decayed wood has been found, indicating that timbers had been used for the roof. On Black Mountain the only traces of wood were patches of charcoal, mixed with the earth that filled the centers of the houses. From this it would appear as if the inhabitants had been driven from their homes by fire. This, however, is hard to conceive of unless it be that the crater just to the south of the city became slightly active, and so heated everything as to cause combustion. In this case the ashes from the crater must have all blown away. But this theory can be supported by the fact that the entire lower portion of the mountain is covered with ashes. has completed'a horse | s of cun- | pink and green | three of | ility that the former | sz’mmmlg This shows one of the 3 é J sun-worshipzrs’ abodes in Arizona, as restored by an eminent professor of anthro- pology. 229202929222929222222929%. : : | aridity of the surrounding country, it { would seem strange that a big t of & | people could manage to exist in such y barren locality. But here it must b2 borr in mind that the country was different then than it is now. Thereisa strong probability that at that time Death Valley was am inland sea. Salton Lalke was also full of water, and consequently there was vegetation on the mountain sides. Trees grew where now only rocks exist, and the rainfall was consequently copious. Scientific research points to this, which being the case explains perfectly the ques- tion of sustenance. Taking into consideration the sizcvof | the prehistoric city on Black Mountain, | it must have had a large population. It | covers at least eighty acres, and judzing i by the closeness of the buildings, and add- l'ing to this the knowledge of how the aborigines packed themselves into their houses, there must have been about 5000 | people there at that time. Where are | they now? Simply gone to join the ! countless millions who sleep in the bosom of nature, as all present inhabitants of the earth also must when the time comes. S KEATS' LAST SONNET. Bright star! would Iwere steadfast as thou art— Notin fone sp endor hung aloft the night, i watchip eternal Lids apart, Akt matures patient, sieesless Eremite, oving waters at their priestilke task {ution round earth’s human shores, the new soft-{alien mask ow upon the mountuins and the moors— Mot ottt steadtast, sciil unchaageable, Pillow'd upon my fair love’s ripening breast, To fesi forever 1 s soft fall and sweil Awake for unrest, £U0, stiil to aken breatn, And'so live ever—or eise swcon to deatk. ———————— Lik The m Of pure a Or gazivg © FIEEEITETEEEVSBTB800¢8 The photographs from which the illustrations on page 22 were made were taken by Hodson of Sacra- mento especially for “The Sunday Call” : Connnnnsnannng