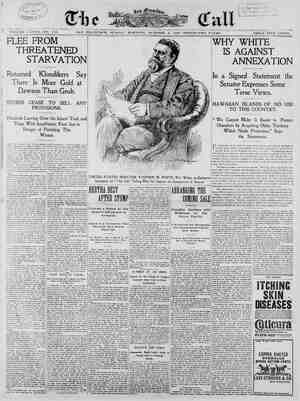

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, October 3, 1897, Page 22

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

22 THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, OCTOBER 3 1897. OAKLAND'S FAIR APOSTLE OF SPIRITUALISM Madame Montague and Her Wonderful Psycho- metric Readings and Powler of Looking There is a stir 0! expectation in the ball. A female figure glides swiftly and silently up the central aisl~ throws off a long cioak and steps unassumingly upon a platform all redolent of fragrant purity. Flowers entwined upon the platform cur- tains, flowers massed and scaitered onthe piatform pedestals, flowers breathing rich aroma from the platform steps. And, amid this suggestion of spiritual essence the Apostle ot Spiritualism, a plcturesque figure, her red robe caught in by a long scarf of old gold sitk, her short hair stand- ing like u dark aura round her clear-cut, sensitive face—a vivacious, pathstic, F¥rench face of the type which always suggests a strain of Slavonic blood lurking in its veins. Certainly “Madame” does not pose for effect. Her first movement is to subside meekly in a chair while her cengregation sings *Nearer, My God, to Thee.” Madame does not join in the singing, neither does she, to all appearance, take note of her surroundings. She has her own private duties to per- form, she is acquiring the receptive or “inspirational” attitude, and as I watch her mobile face I become aware of a marked transformation. Rapidly she passes, once or twice, her hand over her brow, across her throat, and gradually the clear, open glance is contracted, the pu- pils draw together, the sensitive mouth | becomes set, the delicate nostrils acquire a pinched look. So she sits for a few mo- ments, self-absorbed, as one in the mes- meric state. gesture, she motions for the hymn stop, and rising steps iorward, flower- framed, to address her audience. Her first words are not a lecture, but an apol- ogy. We have already learned that Mme. Montague is unable to lecture to the Psychical Society to-nicht. has been giving us his views upon vibra- tions and Madame's explanation now comes in liguid, sonorcus tones that at once awaken responsive chords. cent is French—markedly so. Baut it only accentuates ths precise in- tonations, the well-chosen rhythmic phbrases, which distinguish the utterance of an acquired and carefully tongue. As she tells of the mourning in which the society has been plunged, of the funeral of yesterday, the memorial | d services of to-day, the vacant chair mark by garlands of flowers, her hearers’ sym pathies go out to ber and to the poetic exposition of her spiritual doctrine which clothbes the departed with a new form and an ever-present magnetism. Then, with quick, graceful | to | A substitute | Her ac- | studied | Beyond the Veil. | strangers who have piled their possessions on that pedestal. I have no clew to the | mental question each asked while laying down a ‘‘subject,”” and my atten:ion limits itself to the picturesque, red-robed figure that handles the articles and flits gracefully about the platform. Every movement is dramatic, every word tells; but 1f this be art, then hae Madame acquired the perfection of spon- taneous art; for actions seem emotional and unstudied, glance and expression have the strained look of a soul at high tension harkening to far-away influences. “This is an old watch and chain,” says Madame, casting the chain round her neck and pressing the watch to her tem- ple; “you the owner 2" She pauses, walks to and fro rapilly, listens to the tick, tick. “Yes, you are.” And then follows an exposition of the owner's character, his physique, his am- | bitions, and in more veiled language, his | d ficulties, opportunities, duties and proper course of action. “And to your question the answer is yes. Now stand up, you, and say, do you understand 7" A tall, well-built man stands up with | the nervous air peculiar to the modest sex in such circumstances. Madzme | points at him with a litile bow. | i Am [ right?” 1 guess that’s so, Madame.” She has already turned away and is probing another watch, walking up and down, listening, thinking, with restless, supple movement. Again the character is read, directions are given, hope or pa- tience is suggested. And so through a strange gamut of trinkets linked to per- sonal histories. teresting to but one individual | rest it is an enigma. recipients look well content, how is the | critical outsider to be assured that they are not fooled by a lucky phrase or a trick To the | of imagination? Suddenly there is a | pause in the proceedings. Madame | speaks wearily: | “‘There are too many,” she says. I cannot read them all to-night; I am not | strong enough.” | Instantly 1 am seized with self-assertive egotism. 1too want my proofs and there is among those “subjects’’ a small, dull coin which is my psychometric test. Is | Madame going to overlook it? The rest may go, forall I care, but she must, she really must let me find out whetter there is anything in her professed insight. I try to start a brain wave: “Take up the little old coin, take up the “Itis your wateh? Do you understand? | And, though the | But each reading is in- | i 4 | “But the change is to us a pain,”’ adds | little old coin,’’ I repeat to myself stub- | the speaker, with her rapt look and her pretty trick of tongue. *The emotion of parting with what is familiar exhausts our frames, and that is why we have been too tired to address you to-night and why we must crave your induigence if we fail in the work we shall try to do.”” And herewith follows a little bit of ad- vice which does not sound inspirational, but exceeding human. Madame, insisting on the necessity for harmonious inflv- ences, requesis every one who is noten rapport with hersentiments and her work, any one who has adopted an antagonistic frame of mind, to “‘kindly consider them- | selves dismissed None ‘‘consider themselves dis- missed.” Every one, on the contrary, adopts the expeciant attitude, ewaiting developments, which are many in pros- | pect. Foron a small pedestal are heaped divers personal adornments appertaining to various members of the audience, and these are to be subjected to “psychometric readings.” Now, the interest of a psychometric reading is1n inverse ratio to your con- nection therewith. Iknow naught of the | bornly, and 1 know that a brain beside me | is exercising its will power 1n unison. Madame looks pathetically at the heap beiore her. “I feei so many currents coming to me,” she says slowly; *‘there | are so many people who are each wishing me to take their thing I cannot attend to all, I am tired.” [ake the little old coin, the little old coin, the little old coin,” repeatsitself over and over in my head, and my heart beais fast with the energy of my wish. “This is says Madame, taking it up quietly and eying it with a puzzled air, The brain wave nas quivered; I am sat- isfied. *‘Very sensitive nature,” 1 say to myself smugly; “evidently a telepathic business all through.” ‘A very curious coin,’” proceeds Mad- ame, “and you, you have mistaken your vocation.”” My telepathic theories are discounted. Iam quite convinced that I have fourd my vocation. It is only guesswork aiter all. “You ought to have been a—-"" Ismile as she names my suitable pro- | wise attuned to tne introductory hymn. | | * | | | fortune-telling business in her analysis of | the real object of my greeting. 4 | and nerves patently quivering to the ex- | a very singular little coin,” | fession; she hasapparently mistaken even my sex. “But vou have preserved the gualities | that made it suitable,”” continues the thoughtful voice, “you are—"" Then, in a flash of thouzht, T am taken | backward to the forgotten areams of youth, the longings for a profestion which circumstances never allowed me to enter, | the conviction that I should find therein a satisfying field of usefuiness. Do brain waves carry sleeping memories with them? | Modesty forbids me to mention the said qualities ; vanity compels me to add that 1bave had the same attributed to me by | enthusiastic friends. 1am very well satis- fied with Madame, Bui my satisfaction turns to astonish- | ment wnen she makes explicit allusicn to certain anxieties wuich perplex me, wind- ing up with the remark: “Your mental question is answered yes—you will have news of that very soon. Whose is the coin ?" *Mine,” I answer, and fall into a brown study, while some who have had no *‘read- ing’’ allowed them stand up for mental questions. My mental questions are all about Madame. Does she really speak nder inspiration”? Her last remark | might indeed have been the chance hit of | a fortune-teller, but there had been no | character. Whatever she may be—tel- epathist cr psychomeirist—one thing she assuredly is not—an impostor. I deter- mine to investigate further. Madame’s bright smile of welcome fades away in shy nervousness when she learns | “Ob no, please,” she protests. *'I do not like that, | Tamso afraid of publication, so fright- | ened of anewspaper.”’ I humbly point out that I am not a | newspaper, but & woman, with consequent | sex sympathies. “C’est vrai,”” says Madame thoueht- fully. Possibly the qualities she discov- ered in me are vouchers for my good faith: anyway, the smile steals back into her eyes. “Well, you will not judge me by to- night?’ she pleads, “1 am not well, 1| have done but half my work. Come to see me some evening when Iam in San Francisco. 1 may do better then.” AsIcome away I remember that my sex and occupation are the oniy informa- :ion she hasacquired by natural means. She does not even know my name. | The second experience is less poetic. | The San Francisco hall is large and cola | and half empty; the platform is flower- | less; the audience has been de-magne- | tized by a stereoscopic iecture and is in no | Madame, as she stops on, is plainly con- scious of the unsympathetic element and makes a pathetic little allusion to the difficulty of working under such condl- tions. Her work to-night consists in an- swering written questions. From a table heaped up with little slips of paper ques- tion after question is drawn and read aloud, while Madame, with strained ear tendea taper finger-tips, @stens, snatches, | tears up the paper almost ere tue reader bas finished, utterine her voluble answer without pause or hesitation. And if a club of select idiots bad combined to pro- duce the evening’s arrangements they could not have prepared a better list of | queries. Of test in the ordinary sense there is never a vestige. You might as well look for test questions in a page of Ollendort. But one marked test there undoubtedly is—of Madame’s extraordinary readiness, | command of Janguage and capacity for delivering an extempore harangue on the most unpromising texts. Whether she be | swer questions, she never troubles over | and straightway fell in love with them. | . asked her opinfon on stage qualifications spiritual communigz, social inequalities, the character of the Pa‘riarch Abraham or the prospects of the questioner, she never loses the fraction of a second in con- sidering her answer. It pours from her in a torrent of graphie, piquant phrase. The most trivial query makes a good text for the exposition of her views. And the views of Madame, or rather of the WE she introduces so quaintly, are by no means commonplace; rather they are calculated to make the hair of the ortho- dox stand on end. “No, WE do not con- | sider Abraham a model character,”” cries the speaker, and forthwith follows an analysis of the vatriarch which would petrify the ordinary Sunday - school teacher. *No, we do not wear the cross as areligious symbol, but as an emblem of tke forces of the universs,” is the pre- liminary to a discourse on electricity. But whatever the views expressed by Madame when in the plural state thev are invariably directed toward integrity of life, nobility of aspiration, development of the higher self. Naught but what is re- fining and purifying is to be learned from the active, excitable figure, with its eager gesture and impassioned words; while now and again comes a flash of keen hu- mor, as when it is said of the written American constitution that its most elo- quently suggestive items were its blanks, And of the woman herself, the unas- suming, winsome woman off the platform who is no longer WE, what shall I say? First and foremost that she has that faith which, according to George Eliot, is the true mountain-remover—faith in herself. Madame firmly believes in her mission: ks the earth as one ‘“‘encompassed with a cloud of witnesses”; she is never | alone, never iree from spiritual compan- | ionship. From earliest childhood she has heard *‘voices.”” From earliest childhood she has spoken words that seemed to be | dictated by an outer, not an inner, con- sciousness. And now, when she ascends the platform, whether to lecture or an- the manner or the matter of her speech; but she is the instrument through which some higher influence breathies its mes- sage. Yet Madame, spiritualist pure and sim- ple though she claims to be, talks theoso- phy, as Monsieur Jourdain talked prose, unawares. True, she prates neither of Devachan nor Nirvana. Yet, when she telis you that her “influences” are not | drawn down to her, but that she rises up to them, when she beiieves that something of Lerself passes out of her when under influence, that, while preserving her own | individual consciousness, she becomes two or three personalities, moving in various spheres, [ bethink me that a theosophist would surely open his textb ook and, pointing to certain oriental-looking words, | claim Madame as a fellow disciple. Shakespeare mentioned, a littie while ago, that there are more things in Lheaven and earth than our philosophy dreams of, Despite the progress of science we have not vet contrived to improve upon Shake- speare’s dictum. Science, despite itseif, works for immaterialism; all its provings reveal the existence of unsuspected, im- patpable forcee on which depend universal life, forces whose very strength lie in their | inberent delicacy. When natures like Mme. Montague's claim to have come in undefinable contact with some of these forces we cannot oppose the argument of our own less delicately organized systems. Till proof to the contrary be shown we | can but suppose that to certain finely bal- anced supersenses it is given to calch glimpses “behind the veil.” Rose pE BoHEME. | Why Wiggins Kfloved. Mr. Wiggins has moved again. Three weeks ago Mrs, Wiggins beheld a row of new houses up on Steen’'th street nere were seven of them in line, in every way modern and delightful, and the middle one was vacant, The nextone to it on the left was, moreover, occupied by the clergyman under whose ministrations LA NOVIA DE MIS SUENOS. (The Sweetheart of My Dreams). Written For THE CALL By GERTRUDE R. SPELLAN. | gotten to take with him. | paternal orders, an extremely indignant 3 : | | a wish for scme steam beer, he acquiesced | Mr, Wiggins manfully tries to keep awake every Suuday, and the occupants of the other houses were guaranteed by the agent to be everything that was lovely in the way of neighbors. The Wiggins family moved, ol course, and then Mr. Wiggins’ troubles began. The houses were charming, with bulging bay-windows, quantities of colored glass and unlimited . jigsaw adornments, but they were as like as peas in a pod, and Mr. Wiggins is both near-sighted and absent-minded. A few days alter taking possession of his new abode he came home and found a dog reposing on his doormat. Mr. Wig- gins abominates a dog, both a carrier | and distributor of fleas and for itself | alone, therefore he proceeded to kick this one down the steps with neatness and dis- paich, to the canine’s evident astonish- ment and loudly expressed dissatisfaction. No sooner did his ki-yis begin io rend the air than the door opened and a tall and extremely irate female, arrayed in a gorgeous teagown, appeared upon the threshold and demanded to know, in tones the reverse of amiable, what pessi- ble right he thought he had to come up there and kick her own dog—her blessed little Mopsy—off her own porch. He had made a mistake and turned inat the gate of house number two, instead of bisown, and although he made full ex- planations and & most humbla z2pology, it was quite evident that he had created against himself in the mind o!f his fair neighbor a prejudice that couid noteasily Le dispelled. | Admission day Mr. Wiggins passed in the bosom of his famlly, and, as usual, spent a good deal of his time in band-to-hand | conflicts with his various offspring, whom he declares are utterly spoiled by their mother while he is at his office, The youngest, a boy of 5, is especially obstreperous, and always appears to act his worst when his father is at hand toob- serve and lecture about it. He rather out- | did even himself on this particular morn- ing, and succeeded in getting an extremely | raw edge on his papa’s temper, although open hostilities were not entered into until, because he was not allowed to go downtown with his elder brother, he set up a yell that would well nigh cause a Comanche Indian to pale with envy, and kept it up regardless of parental com- mands and threats. At tbis juncture Mrs. Wiggins requested her husband to run after the departing one with a package which she wished him 1o carry to a friend, and which he had for- Mr. Wiggius obeyed her mandate, leav- ing the door open behind him, and coming back found his youthful antagonists ill sit- ting blubbering on the stairs. To pick him up, invert him, and place a few solid slaps were they would do the most good | ¥as but the work of a moment, but as be | put him down to cool off and meditate | upon the undesirability of defying the | gentleman came upon the scene from the interior of the house and “wanted to| know, you know,” in decidedly vigorous ana idiomatic English. It was his rignt- hand neighbor, whose door had also stood open, and his own son was stiil howling unchastised in the hall next door. ! Last Tuesday was unusually warm, and | Mr. Wiggins had a hard day at the office, So it was that when, after the chilaren | hed gone to bed, his brother-in-law, who | had dropped in for the evening, expressed in the idea at once. Provided with a large glass pitcher, he hastened to the nearest grocery and in- vested a dime in the foaming, ice-cold beverage. Deitly concealing his purchase \ with an open newspaper—since it is not | his babit to indulge in suen dissipations, | and be felt guilty according!y—he hurried | up the street, dashed into the area door, | threw the paper on the floor and set his overflowing pitcher in the center of tae dining-table. “Hurry up with the glasses, Susan,’’ he said, “and don’t make us wait until i's as | flat as a flounder. I can’t abide it that way.” And then—and not till then—he per- ceived that instead of his wife and her brother it was the Rev. Mr. Blank and his helpmate before whom he had set his per- nicious and reprehensible refreshments and that they were both shocked into horrified and stony silence by this sudden e = M MR TR T D TR SO X W R RS BB <ol b SN e T FES———_ — 3% { own home. YOUNG GALIFORNIA ARTIST HONORED IN GERMANY. Another California boy is rapidly climbing the ladder of fame. | many of the boys of the Golden State have done this during the last decade, but | few have risen as fast as the art student, A. Altman. Only a short time ago this young man was a student in the Hopkins Institut: now he is an acknowledged painter in Europe. would have been almost unrepresented at the fountain head of art this year. he has borne the standard sobly. Of course, Were it not for him California But At the last Salon Mr. Altman exhibited several pictures, that were hung in the best position, and brought forth the most favored encomiums from critics. tion to the Salon, he exhibited at different well received. In addi- places in Europe, and has always been At the special invita‘ion of the committee, he sent two pictures to the King of Bavaria’s big exhibition in Munich. The standard of this has bsen said to be the highest of any exhibition ever made. This exposition opened last May and closed a few weeks ago, when the awards were made. with an honorable mention. in this city. Mr. Altman on the eventful day was quite surprised to find himself Word to this effect has just been received by his father His two pictures—a landscape and a portrait—were well hung, and when the King found out who the artist was he called him up and congratulated him. He mentioned that the pictures were a surprise to him and that Calitornia must be a | great country to produce such a promising young artist. Not only has Mr. Altman improved in his art during his absence abroad, biit he ones with great ease. At present this young artist ison a abont two months. | has also become a thorough student of languages, reading and writing the principal tour of the galleries of Europe. After | finishing them he will start home, and is expected to arrive in San Francisco in He will bring a large collection of pictures with him. and unexpected revelation of his iniquit- ous proceedings in the retirement of his | Friday night Mr. Wiggine attended a | meeting of tue Society ior Ethnological Research, and returned a little before midnight. His latchkey did not work easily, but he had a number of others on | hisring, and one of them turned the bolt. Taking off his shoes he turned out the dim hall light, thoughtfully left burning on his account whenever he goes out of an evening, and went softly up the stairs. | There was a faint lightin the bedroom. He had removed his coat and vest and necktie, when a voice from the bed said sleepily, “Is that you, George?” Mr. Wiggins’ blood ran cold through his veins at that, for his name is not George, | neither was that voice the voice of his Susan. He was in the wrong house again, and, overcome with confusion, he caught up his discarded garments and without a | cently intruded. | rang word retirel in as zood order as possible from the room into which he had so inno- *‘Geor:e’’ himself, com- ing in at this moment, met hiri at the head of the stairs, and taking him-to be a burglar laden with booty grappled with him, and they both rolled to the lower floor together. Mrs. George's screams through the mneighborhood and brought two policemen to the spot, while they, each taking the other for a marauder, were vigorously dusting the carpet with each other's bodies in the lower hall. Mr. Wiggins bore away a cut forehead, a black eye and a sprained shoulder from the fray, and as soon as he was able to go out without attracting invidious attention he started house-hunting. To-day he occupies a houmse which in size, shape, color and position differs en- tirelv from all its neighbors, and he is once again at peace with the world. FunEcar McVamox, T ) S S SR R S S S S S < S S S~ M I S~ -