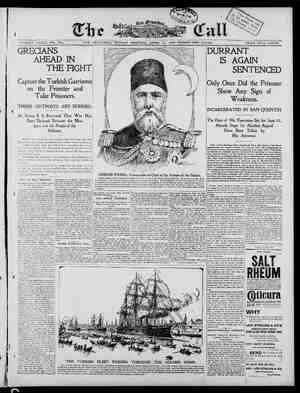

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, April 11, 1897, Page 19

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

| THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, APRIL 11, 1897. 19 In one of the charming villas at Belve- | dere lives George W. Miller, who, some- | thing mere than forty vears ago, was first | lisutenant of the volunteer company | raised at Port Orford, Or., to aid the regu- | lars in the defense of homes and the sup- | pression of the Indians in what is called | the Rogue River Indian w An allusion to the massacre in a recent publication has awakened in his mind personal reminiscences of that struggle, in which a little band of whites success- fully resisted the desire for their exter- nation which lurked in the breast of old Chief John of the Tootootneys. Port Orford was at that time a collec- tion of perhaps a dozen houses, with the | fort, in which Major Reynoids of the United States army was stationed with ibly thirty-tive regular soldiers. he cause of the outbreak was, un- , 8 system of indignities prac- ticed upon the Indians by a number of lawless whites,” said Mr. Miller to bis visitor from THE CALL. | “One of the outrages kitterly resented by them was that of robbing their burial grounds of the boards with which it was customary for then to protect each grave. | These boards were hewn with much labor | from great cedsr trees and with tools that | a carpenter would have scorned. They were Irom 2 foot (o0 two feet in widih and | of various lengths. “Whenever lumber for certain purposes | was needed, there were those in the com- | munity who did not hesitate to appropri- ate the ed boards, without re- | zard for the icance applied to them by their lawful owners. Protesta- tions upon the part of the Indians or set- tlers possessing & sense of justice were met with either insult or indifference. ‘At that time there was no dearth of the tiotsam which society ever casts upon the frontier. A certain number of young men, whose ages ranged from 25 to 30, were banded together and gave full play to inclination without regard | 1 They affected the long- wless cor haired, buckskin-suited style of the dime- ces. eq 0. Someof them deferred to the law of purchasing their squaw rs defied the custom, and, in- friends and relatives into re- shing the squaws on whom their | v lighted, bore them away after the fashion of barbaric conquerors. “Before the feeling generated by these and other indignities had arisen the In- dians were peaceful and friendly. On | finding that their primitive shell coin could not purchase the white man’s sup- | plies they willingly gave labor in ex- change. This work was done principally by the squaws, who dug gold or helped in unloading vessels when tiey ventured into the dangerous, breaker-beset harbors. “The Indians were four years preparing for the war which they fancied would rid them of the whites and avenge their wrongs. “Sea otter were at tbat time plentiful and numbers were caught by the Indians. The usual price paid by the traders for a skin was three rifies, and in this way arms and ammunition were purchased. These were carefully cached for the contemplated | outbreax. “The greater part of the guns traded to the Indians were what was termed the United States suger gun. These were short-barreled affairs holding an ounce i, which was discharged with a rotary I'he cash price paid for this gun motion. was $12. “When rumors of impending trouble were noised about, the traders, the ma- jority of whom were what is termed squaw men, remarked with complacency that under any circumstances they had no cause to fear the Indians, as the presence of their squaws was a protection. It was significant that these traders were the first to fail victims to the wrath of the savages, and were all mercilessly tor- tured. The most prominent among them was Ben Wright, known as an Indian fighter, who for such services drew a pen- | sion from the Government. The succes- sive slaughter of other weli-known char- acters followed and soon brought us to a realization that a bloody war was full upon us. Plans for resisiance were soon put into operation. A numoer of men in | whaleboats started to aid the settlers liv- g at the mouth of Rogue’ River. The | effort was futile, as the Indians attacked them when about to land, killing all save | one of their number, who escaped to the | fort. Among them was a merchant named | Jerome, who bad taken advantage of the | expedition to collect a debt from & debtor | at that point. “The instigator and leader of the In-| dians, Chief John, was acknowledged by | the white officers to be a warrior inde-d, | a crafty tactician, who tried to the utter- | most the military skill of his white ad- versaries. Thus the message was called from mouth to mouth with rapidity and suthenticity. *“When Colonel Buchanan came to the relief of the disheartened soldiers he re- quested John's presence at camp, sending men as hostages, and endeavoring to treat with his red foe, but the warrior listened to bis propositions disdainiully. He de- sired no treaty, and, looking the officer steadily in the eye, declared that he pre- | shore were their provisions, their stores of | ammunuition and their families. For a long time they successfully resisted the efforts of their enemies to cross. “The story has often been told of the | construction of canvas boats in which the | soldiers reached the opposite shore under protection of howitzers planted upon the bank above them, and of the destruction by them of immense stores of dried fish, Besides employing the usual | ferred to fight him man to man—a state- [ which at that sea<on of the year formed | signal fires resorted to by all savages, he | ment which the angry general could not | the chief article of Indian food. The ber- effective human Knowi that the invented a unique a; telephone system. resent, as he felt inclined to do, owing to the dangerous position of the three sol- | ries upon which they might have subsisted | bad not yet ripened, and their attempts to i yet rip women of his tribe would be safer than | diers held by the Indians until the return | catch further supplies of fish were frus- men from the guns of the soldiers, he sta- | tioned young squaws at intervals of 300 | yards from one point to another between | whicn he desired communications to pass. | of their chief. “The Indians endeavored to keep the waters of Rogue River between themselves and the white men. Upon the further trated. Siarvation or surrender stared ‘lhem in the face, and a dreadful scourge of sickness, caused by lack of food, set in among them. | ful; “When General Buchanan sent word | main at home upon a certain night. for Chief John's surrender, the Indian re- plied that through necessity he yielded to the great Tyee’s command. When the order ‘was given for them to leave the vicinity for the more fruitful northern reservation a chief called Tagrnatia sor- rowfully protested. z *“*I was born here,’ said he, ‘and here I hope to lay my bones when I die. I have always befsiended the whites and in my heart is no enmity toward them.’ His request was unheeded and with the Indians well known to be hostile he was commanded to take his departure. “Tagnatia was an Indian of fine phys- ique, being fully 6 feet tall, of a benevo- lent and intelligent countenance. He was noted among his people for his ingenuity, and among other useful things could make an excellent saddle similar to those used by the Mexicans. “When the Indians, some 1500 in num- ber, took their departure they passed through the lines of the soldiers stationed at Port Orford. They formed a procession which was the personitication of wretch- edness, poverty and despair. Old men and women were led in their blindness by younger members of their tribe or family. Women weak irom sickness bore heavy burdens or children upon their backs. ‘Woll-eyed warriors stepped with an air of haughty nonchalance and a look of baf- fled hatred upon their dark faces. Troops of children crept along, ragged, dirty, piti- and leading his people was Chief John, mounted upon & sorry mule, a look of indifference on his face, his eyes, which seemed to observe nothing, fixed straight before him. *Port Orford was never attacked by the Indians, though scouts were often sent by them to take account of and report any opportunity for slaughter. These scouts traveled at night, running swiftly upon the beach and in the water's edge to hide their jootprints. In spite of this precau- tion, however, they were usually seen by the watchful sentinels and a shot sent them precipitately into the sea. ‘A number of peculiar incidents of that bloody period remain in the memory aiter the general dark background has worn dim. At the beginning of the outbreak, I remember, a blockhouse, two stories in eight and forty-five feet square, was builton the outskirts of the little town; | in this blockhouse families found shelter at night. “There had been no indication of the presence of Indians for some time, and one of the families, growing tired of the constant moving to and fro, decided to re- Be- fore morning, however, an alarm of In- dians was sounded, and the husband and wife, each catching up a child, started for the blockhouse. “They had gone but a short distance when it was discovered that some much needed belonging had been forgotten. The husband decided to return, bidding bis wife hasten on to the blockhouse, which there was two ways of reaching from their dwelling—one a short cut through the thick bushes, and the other by a wagon road. “The wife chose the former, whilein returning the husband took the road. Not overtaking her the safety of his wife ana child weighed upon his mind, and the necessity of silence was entifely forgot- ten. “He loudly called her name and she, though realizing the danger of such an outburst, felt compelled to answer. “‘Her exact location and the progress she was making next caused him anxiety, and his call was repeated. As expostula- tion was impossible the wife again re- lieved his anxiety by, loudly calling her answer. So through the strip of wood- land they went proclaiming themselves an easy prey to the tavages, who fortu- nately for them were biding their time or committing depredations elsewhere.” Although surrounded by dangers the younger portion of the community felt the need of amusement, and a dance was ac- cordingly given. They congrezated in the only hali the place afforded, stationed pickets to guard sgainst surprises, and, stacking their arms conveniently at hand, proceeded to enjoy themselves to the accompaniment of a brace of fiddles. As young children formed an import- ant part of the community, and nurses were not a feature of the frontier, each mother participating in the gayety—and young mothers were in the majority among the women—placed her child upon a convenient bed in the dressing-room and unincumbered joined the dance. One of the babies so disposed of is to- day a prosperous business man of our city. The sympathetic members of that party received a shock in the unexpected appear- ance of an elderly woman who but two weeks before had a son murdered in the whaleboat expedition. Yet in spite of his awful fate sbe joined in dancing and made merry with the rest. Her utter heartlass- ness was a circumstance never forgotten by those who were present. Mr. Miller exclaims bitterly azainst the blindness of the Government to the inter- ests of its law-abiding citizens in depriv- ing them of fertile and accessible lands | and bestowing them upon the unwilling Indians, who preferred the thick woods and barren shores from which they were driven and which were best suited for their savage needs. “God made that wild country for the { Injuns,” dectared Mr. Miller in conciu- sion, "'and the Government made a fool of | itself in driving them away and giving them land that the white man was bound | to need some day.” CLARA 1zA PRICE. Wi\erZEQarflzld Was Shot. The marble tablet that rested in the south wall of the ladies’ waiting-room of the Baltimore and Potomac Railway Com- pany’s depot and the brass star placed in | the tiled flooring of the apartment to mark the spot where President Garfield fell | when assassinated have been removed. A superstitious dread on the part of the | traveling public of a constant reminaer of & tragedy seems to have led to the removal of these monuments. The immediate | cause of the removal of the tablet and star was the fire which occurred in the depot on the night of March 4, which damaged the tablet to such an extent that the offi- cials of the company declared it was not in condition to be repiaced. A portion of the marble tiling also had to be removed, and although the metal star placed where the President fell might have been put back in its old place, it was permanently removed, and the spot is now marked only by a piece of red tiling, which would pass unnoticed excent to | those familiar with the place and the | tragedy that was enacted there. Officials of the company stated that there Was no purpose In removing the monuments except that they haa been damaged by fire. From other sources it | was learned that there had been wuch | complaint onm ths part of the travei- ing public of having the horrors of the assassination constantly recalled to their | minds when going through the depot or | waiting for trains. To such an extent has | this feeling prevailed that the company has long regarded the reminder of the | tragedy as a disadvantage, and it is be- | lieved by many that the oflicials were only | too glad to have an excuse to obiiterate | the monuments.—St. Louis Globe-Demo- crat. L sy | There is but one monarch of Europe who can show the scar of a wound re- ceived in war. It is King Humbert, who received a severe saber cut at the battle of Custozza. TRYING A young woman from New York, with whom I became acquaint:d while she was visiting San Francisco and stopping at one of the City hotels, de- scribed to me a “chloroform spree,”’ which she declared was in vogue among some fashionable women in the East, and which *‘came nearer to being a bit of nirvana to order” than anything e knew. determined to indulge in one of these ” for “an experience.” Ihave had the experience | I stopped at the drugstore nearest my home, and, with what I trusted seemed like my usual unconcerned and rather superior manner, asked the dapper clerk for “four bits’ worth of chloroform.” He looked at me with wild but decidedly dis- composing surprise. ‘How much of what, Miss?”’ he asked, and when I repeated my order with sever- ity, conscious that my ears were beginning to burn furiously, he disappeared behind tne fence erected to conceal him and his associates from the public eye when en- gaged in putting up prescriptions. Evidently he consulted the proprietor in his lair, for he returned looking trou- bled aud interrogative, though smiling | feebly. “What did you say you wanted it for, Miss?” he asked, and my face turned the color of an overripe tomato. What did I want it for, indeed ? I certainly could not confide my intentions to him, o I grasped at the first nebular idea which floated across my confused brain. “For my cat, of course,” I answered with asperity, and my questioner looked | relieved. *“Concluded to do away with old Tom?" he said cheerily. “That’s all right, of course, but we have to be particular, you see. Ican'tsell you that much anyway without a prescription, but 10 cents’ worth | will do the business all right.” And then while he was making a thing of beauty out of the small bottle by means of snowy paper and pink string he toid me just how to arrange mstters so as to make poor old Tom’s taking off a painless certainty, and I departed smiling. Arrived at home I made my prepara- tions with eager haste, and Jying upon my couch uncorked the vial and tipped it up on my handkerchief two or three times. Then I pulled the cover up over my head and snuggled dow: among the pil- lows to enjoy my “bit of Nirvana.” Ugh! Was ever anything so intensely, burningly, disgustingly sweet as the smell of that chloroform? I shuddered from head to foot s the first whiff of it went up my nostrils. The second sniff was not o bad. At the third 1 became conscious of a singular rhythm- ical buzzing and throbbing, famnt and far off, to which I seemed compelled to listen with the greatest intentness, and which grew momentarily louder and louder until it seemed like the deafening rush and roar and rattle of a locomotive comingat full speed through alon %moun- tain tunnel. A thick cloud of pitchy smoke seemea surrounding and hali-suffocating me, and then suddenly a shower of tiny fiery sparks glittered and danced in the dark- ness like millions of fairy fireflies, The roaring grew fainter and fainter, ana became again a rhythmical murmaur, a droning undertone, to the vibrations of which the sparks began to arrange them- selves, as fine sand does on a shect of glass A CHLOROFORM SPREE® when a violin is played close to it, in a| beautiful series of geometric figures, squares, circles, triangles, and_every con- | ceivable modification of those forms. A moment or two and the bits of fire, as they ranged themselves side by side, lost their individuality and. merging into each | other, became an intricate lacework of | The threads grew thick and heavy; the hues, barsh, aggressive and disagreeable, |and the artistic marvel changed into an | closer and closer. | immense curtain of coarse woolen che- |cold and dank, as if it came from a char- | nille, oruamented with row after row of | nel-house, struck against me with 1rre- thick and heavy chenille fringe. A sudden sense came 10 me that every- | thing, until it seemed as if it were going | colors a confusea mixture of conflicting | to envelop and stifle me in its horrid The rushing roar came A sudden blast of air, | crawling folds. | sistible force, and I felt myself falling. I caugnt desperately at the lower fringe golden threads hanging between me and a | thing around me was made of the same | of the living curtain, but the slimy, twist- dusky background, which now began to | material, that I myself was covered with | ing strands stipped through my fingers or glow with asoft crimson radiance, deepen- ing to purple, then brightening to vivid | scarlet, as if a forest fire were raging fiercely but fitfuliy behind a light screen of drifting fog. a chemlie-like fur, and that my fingers were pieces of thick chenille stiffened with bits of wire. The aroning undertone of sound-beats gathered force and volume until it be- DAYy ——— } broke in my grasp, and then — | Topened my eyes to fina myself lying | limply over the urm of the sofa, with my | brother-in-law and the doctor bending | over me, slapping my hanas and shaking \ 4 ffi'”\ e ““1 opened my eyes to find the doctor and my brother-in-law bending over me.” The shimmering meshes of the lace grew finer and closer. The glitter and glow faded, and before me hung a priceless piece of rare old tapestry, a marvel of de- sign and workmanship, in which the colors were softened and harmonized and blended as only time himself can soften and harmonize and blend the crude re- sults of human invention. It was an exquisite fabric, but even as I gazed upon it with wondering delight a creeping shiver passed over it, spoiling its beauty, as a sudden squall roughens and darkens the clear surface of a lake. came once again a rushing, roaring, pur- suing terror. The heavy curtain swung toward me as though a strong wind was blowing against it from behind, and as it came nearer a great wave of disgust end horror swept over me, for I saw that the whole fabric was composed not of chenille but of millions of earthworms, which began wrigghng, squirming, twisting, writhing, stretching out and contracting until the entire drapery was a revolting mass of 1n- cessant, loathsome movement. Nearer and nearer swung the odious and rolling me about with a vigor which was decidedly painful. I was deluged with cold water. There was a choking smell of ammonia in the air. The windows were wide oven, and my sister was in the midst of a frenzied attack of hysterics in & near-by armchair, under the sympathetic care of the parlor- maid and the nursegirl. } Let us pess over the scene that followed my return ‘o consciousness. It seems that instead of ‘‘behaving like an angel” I had groaned so sepulchrally that some one had come in to see what was the mat- ter, and jumping to the conciusion that T had tried to commit suicide had made things pret!y decidedly lively in that vi- cinity without delay. I exclained matters as best I could and was scolded and then forgiven, of course; but my punishment came all the same. For three days and nights 1 shuddered through existence, smelling, tasting, thinking of nothing but the nauseating, overpowering, all-pervading odor of that abominable drug! I lived and moved and had my being, apparently, in the center of a cloud of chloroform vapor, and it made me s-i-c-k! So sick that I could neither eat nor drink nor sieep, nor do anything but shiver and squirm and writhe internally and hate myself for be- inga weak-minded idiot envugh to get into such a state of utter wretchedness. When I confessed the truth to our doctor he looked so grave, and told me such dreadful things about the effects of such “sprees” on mind and body, that nothing could tempt me to do anything of the kind again even had my initial ex- perience been pleasurable—which it most decidedly was not. Thank heaven, our San Francisco girls do not feel the need of indulging in such dissipations! And as for the -girl from New York, she can go to—New York, for all me, and spend the rest of her experi- mental existence there, and no tesr of regret from my eyes shall saaden her de- parture. FuNEGAL McVAHON. An Easter Birth. Again the flower-shoot cleaves the clod, Again the grass-spear greens the sod, Again buds dot the wiliow-rod. The sap released within the tres Is like a prisoned bird set {ree, And mounteth upward buoyantly. Once more at purple evening-dream The tender-voiced, enamored stream Unto the rush renews its theme. How packed with meaning this new birth Of all tne growing things of earth— Life springing after death and dearth! Thou, soul, that still dost darkly grope, Hath not this, in its vernal scope, Some radiant resurrection hope ?— —Clinton Scollard in April Ladies’ Home Jour- nal A Georgia Negro Prodigy. Robert Gardhire is a negro and an un- educated one, but when it comes to figures he can’t be stopped by any mathemati- cian in the worid. Heis a humble res; dent of Augusta, and is employed as a iaborer at the Interstate Cotton Oil Com- pany. In multiplication Gardhire is as quick as thought. Belore the average person can set the figures down with a pencil Gardhire has giverf the correct an- swer, and yet he cannot say how he does it. He was asked what was the sum total of 99 times 67, and without repeating the fig- ures to himself, Gardhire answered off- nand *6633.” *“How much,” asked some one, “is 501 times 32?” Without stopping a second Gardhire replied, 16,032.” And thus for over half an hour numbers were thrown at him and he gave the correct maultiplication like a flash. 1n the multi- plication of fractions the man is equally proticient, and there seems no limit to his powers, which are almost occult. Gardhire cannot remember when he first became aware of his power and does not even know how he discovered it. He says thut when the fizures are given him ne sees their answer immediately. Simply by glancing at a long line of figures he can tell immediately what the addition is. Augusta Chronicle. ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERY An srcheologicel specimen has been presented to the University of Pennsyl- | vania by the Bucks County Historical Society which proves that the symbol of the cross was known and used in ancient America before the birth of Christ. The importance of tne facts proven by this relic of ancient days was first made known by Henry C. Mercer, curator of the sec- tion of American and prebistoric arch- #ology of the Museum of Science and Art of the university. The object which has demonstrated the interesting facts stated is a spindle whorl. This whorl or weight used to give mo- mentum to the spindle-stick, a thin rod about a foot long pushed for an inch or more through an oifice in the center of the whorl. In discussing thess facts Pro- Strange Spindle Whorl Just Unearthed Symbol of the Cross, Proving That Before the Birth of Christ. the otherday. It was recently obtained— the specimen—by J. W. Detweiler of Beth- | lehem, Pa., from an ancient and probably | pre-Cotumbian grave in the Rio Cauca | Valley, in the Republic of Colombia. Here | the idea of cross symbolism in ancient America, rather than mere decoration by means of intersecting lines, is well brought out by the eight smaller crosses between the arms of the central cross. “To my mind the specimen shows— | First, the cross symbol existed in ancient | America before the coming of Christian- ity; second, the cross symbol carved on a spindle whorl by ancient Americans in just the same manner as ancienv Asiatics and Europeans had carved crosses on spindle whorls before the birth of Chris- third, the identity of a peculiar From a It Was Known in Ancient America [From a photograph taken by Professor Mercer.] fessor Mercer said to tne writer: “The thread materia! used in this spindle at- tached io a distaff held in the left hand | ran to the spindle, which being twirled on the knee and being left free to act, spun or wound the thread. These whorls prove a strange coincidence in the thread- making processes in the Old and New Worlds. Dr. Schliemann founa several thousand whorls at Hissarlik and, strange 10 say, many of them were decorated with the swastika or bent armed cross. Others were marked with the ordinary cross. By the bent-armed cross is meant a cross which resembles two letter Z's, one placed across the other just as if each was a singie bar. 5 “Some of the Mexican spindle whorls are marked with crosses, but none show the design in its symbolic form so clearly s the specimen which I brought to light process for spinning in the Old and New Worlds before the discovery of America by Columbus.” A study of the face of the whorl found in South America showsit to be of ex- ceeding age. [ts general style and work- manship make it plainly apparent that it is the result of the labor of the people who inhabitated that part of South America now known as Colombis, before the star of Bethlehem startled the shepherds. In some particulars it resembles in great degree stone objects - found . in the monuments of the mound-puilders, and also calls to mind certain carvings on im- plements of stone used by the Aztecs, Mexico's early :ettlers. Directly across the center, or rather around it, is a belt, large on each side in point of width, nar- rowing down until in the center the long tudinal lines come close together.