The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, November 2, 1895, Page 3

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

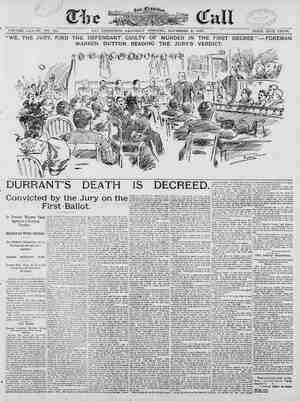

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 1895 murder of a young girl, perpetrated under cir- | cumstances cxlllfi(finc foen unparalleled and traordi depravity, has drawn to this ¥ the attention of a great part of the | Lt the verdict show the | supremacy of the law. | This attention we might well have wished to be spared. for it has accorded to our City & bad imminenc: olly to be deplored. I trust | rou will prove to mankind that while such a i¢ may be perpetrazed in San F co, it | ot avoid detection or g0 without v ment. You have it in your power to prove | at least that spirit of rude justice | und he often righteous indigna- of the mob, born of distrust of courts and v s of jurors o pun- , can have no reason | » is here n becanse g the adm! devotion of ju n, and, with reverence I say 10 that God who thundered spake as wi hou shalt n from ! the voice of many montns a al has been | wrought | kill in s and iragments to- fect whole, | 1 beauty Each of ings and } rlooking the | a, ov ich wili remain, it | » eloquent though and_courage of olds it. Few ¢ utiibuted to the parts knew or_could ch small con ection, but every to do without of his work vor done without : to others whose re- should be to assemble 1s due place, into one ich tempests should never :es prostrate in desolation. he did what was thou, hen e inthe cause entrusted esses have brought to | , their observation, their expe- wed facts, each of no great sig- 1f, are borne 1o you by many u_are building de- , the discernment, 10 One ImMAN Or one woman. | h its companion part withont Slowly has this mon- on end- tireless , each day stronger—each —as it has neared comple- | s weakness nowhere. There ison | at all heights that abiding moral certainty which the 1d together and cement the substance of the case and andid and houest mind to the con- st this defendant, and none other, | ver of Blanche Lamont. ! of the people Durrant is ended. re which has thus been butided, h & mass of indisputable facts his guilt, and absolutel hany reasonable hypothesis of his s 10w before you. W At ust b e end it with the sublime her garb of law, her re lambent purity of the her hand the doer of ve it to 10 ing at the paralysis of hugging to his devil's diul murder, per: er of a church of God peakable and measure- <0 far as the people tragic story, the case is - THE JUDGE'S CHARGE. Full Text of the Court’s Exhaustive Review of the Law of the Case. hv throughout the long trial | late the conduct of the trial. incon- | Itis for you to | 0 a grinning | are concerned in the | ment of the guilty that socloty is protected, thereby affording protection to the innocent. The guiity are punished Lo protect society.. It is not in a spirit of revenge or retribution, or even in a spirit of satistaction, that tne minal law inflicts punishment uvon the guilty; the object of the law is to deter from cruce by force of example; hence, if & person clearly proven guilty escapes punishment the law so far fails of its object, society fails to that extent of protection, and something is taken from the security of life and property. Iam sure, gentlemen, you need nothing fur- ther from me by way of admonition to impress you with the deep sense of your responsibili- ues; Iam equally sure thai these responsibili- ties'you will discharge without fear or favor end without prejudice and with conscientious | fidelity. Ifeel, gentlemen, that it is justly due to the cheerful patience you have exhibited during the many weeks we have been engaged in this trial, and to the attentive care you have given day after day to the vast mass of testimony you have heard to thus publicly recognize and commend your course and conduct as jurors. It is both prover and useful for me here to state, gentlemen, that there is a division of duties between the court and the jury; each has its peculiar duty, and each has the Tespon- | sibility of that alone. The Judge defines his peculiar province. It s the province of the court tostate clearly the rules of law applicable to the_fects and circumstances biought before the jury by the evidence; to decide what shall or shall not be admitted in cvidence, and generally to regu- In some courts, notably those of England, in our own Federal courts, and in some of our sister State courts, itis the practice and custom for the court in its charge to the jury to recapitulate and com- ment on the evidence in the case. Such a course is rarcly, if ever, permissible under our system. Our constitution provides that “Judges heli not charge juries with respect to matters of fact, but may state the testimony and declare the law.” But even were it permissible for the court to comment on the testimony, yet in this case the respective counsel have €0 ex- haustively referred to and rehearsed the evi- dence, which you have heard. that it would be a waste of time and & work of supereroga- tion. It seems almost needless for me to say to you that you shouid consider this case without re- gard to what you have seen or heard or read side of this courtroc Whatever verdict you may find should be, and 1 have no doubt will be, based upon the evidence and the law as will be given you in this charge; therefore, 1ask your calm, earnest and careful attention while I give vou such instructions and explain to you such principles of law as are applicable to and involved in this case. The court ox the great responsibility of the jury. That you fully appreciate the great responsi- bility that resfs upon vouas citizens >f our State and as jurors I am convinced. The ques- tion for you to determine is one of first magni- tude. On the one hand the defendantisac- cuted and charged with one of the most serious crimes against the laws of the land, a convic- tion of which will be of terrible consequences to him, and therefore, Jooking at the case from this standpoint, it requires and demands at your hands the most careful and deliberate consideration. There is another reason which equally_demands at your hands this care- ful and earnest attention, and_ that is the public interest and safety. You have a duty to perform—it may be a pain- | ful one—still, it s & duty and ?t is to be faith- fully and firmly performed. It is a double | duty, guarantecing to the accused that i, after | & fair and impartial trial, he is not found guilty he shall be acquitted; tosociety and the public that justice shail be administered, and the guilty, if so proven, be brought to punish- ment. the solem dates of the law, you are not at liberty to indulge inany sentiment inconsis- tent with or in violation of its strict per- | formance. A limit to the court’s province. You will distinetly understand that in this charge the court in 1o manner or form is ex- pressingz ot desires to express any opinion on the weight of the evidence, or any part of it, or on the truth or falsity of any witness’ testi- | i | | | | or is ot proved. With questions of fact, the welght of the evidence, the credit that you should ive 10 any Witness swo; i the court has nothing to do. These are mat ters entirely within your province and which you as jurors under your oaths must deter- mine for yourselves. The duty of the court, as before stated, is simply to announce to you gllance and p arly demonstrated delivered to the Murphy's charges t the country, and full text of the important document rday herefore given as follows: vas pee r; ior Court of the City and County | of Californis, Depart- te of California vs. W. ith murder. 1 of the jury: It must be s source atification to the counsel in this case, as :d it is to the court, that our respective s are drawing to a ciose,and to you, emen of the jury, it must be doublya congratalation that your protracied s are soon to come to an f us in the discharge of our duties long and toilsome, but far of active stirring oceupa- confinementand restraints e hes imposed upon you; nber, gentlemen, that it is required of all good citizens. is 1Ot of your own choosing 1 you to perform tnfs fm- h is todetermine the great n_this trial between the State r 5t the bar. d s high and responsible public are chosen to perform. Sitting 1 judgment upon the life or responsibility for dministration and ment criminal law rests upon Il constitution and laws of our State ribe that every person accused of crime led to trial by jury, and in mandate you have been our respective avocations < evidence and to determine the 1t question of the guilt or innocence dant. scd was representcd by threc able gentlemen. - constitution and law is gnaran- person the right to be repre- 1. In this case the accused aseif of the services of the three en who have appeared for him, able in their protession, and how well have discharged their duties dant you all know. On the people ars represented by the t Attorney and his assistant, tiie peopie for the purpose of seeing minal laws of the land are en { these gentlemen have ably and v periormed the duties of their office duty tha YOu & rty of a f. : faith for and ab toward t e deic other hand D Jearned elccted b jurors you represent the f the highest achievements of nt is to place twelve good e juis-box to pass upon ¢ the issues submitted to them. his, with twelye honest jurors dual safety, liie and reir just and impartial he enforcement of the law is to the case based upon the testimony which | you have hieard in as concise a manzer as is | consistent with its duty and the importence of the issues involved. re defendant at the bar, William Henry Theodore Durrant, is accused by the District Attorney of this City and County, by an in- formation filed in this court, with the crime of murder, aliezed to have been committed as follows t he, the said Durrant, on about the 3d day of Apri City ana County, did wilifully, uniawfully, feloniously, and of his malice o forethought, kill and murder one Blanche Lamont, othe wise known and called Blanche Lemont, human being. To this information upon his arraignment, duly had in this court. he has entered his plea of “Not guilty,” which puts in issue every allegation of the snid information and charge this plea of not guilty piaces the burden upon, | and makes it the duty of the prosecution be- fore a conviction can be had, to establish to | your satisiaction and beyond’ all reasonable | doubt by lezal and credible evidence, that the defendant is guilty as charged. Act and intent must be in union. In every crime or public offense there must intent, or criminal negligence; the intent or intention with which an act is done is mani- fested by the circumstances connected with the offense, and the sound mind and discretion of the accused, All persons are of sound mind who are neither idiots, i with insanity. As to the intent or intention with which the act charged is alleged to have been done, you must arrive at it from all the testimony in the case, and ali the acts, conduct and circumstances shown by the evidence in the case. Each and every one of you undoubtedly know thet we cannot 100k into the mind of a person and sec what the secret workings of that mind ! are; we cannot read it as we do a book, nor can we produce & photograph of the mind and exhibititto you, and thus demonstrate its exact conditions and workings; hence it is t the law says, and this is based upon = that the intent or intentions with wh act isdone or committed, is to be ascertained and gathered by the jury from all the conduot and circumstances surrounding the commassior. of the act as shown by the proof. hat h an Presumptions of law in regard to intent. There are eertain presumptions of law re- | garding & person’s intent, by which you should | be governed; these are, that & malicious and guilty intent is conclusively presumed from the deliberate commission of an unlawiul act for the purpose of injuring another; there are other presumptions of law bearing upon this question of intent, which the code provides are satisfactory, if uncontradicted, but they may ntradicted by other evidence. They are what are denominated disputable presump- tions, and are as follows: that an unlawful act was done with an unlawful intent, that a person intends the ordinary consequence of his volundary act. The word ful” when epplicd to the intent with which an act is done or commit- ted, 1mplies simply a purpose or willingness to commit the act or make the omission referred to. The words “malice” and *‘malicious” import & wish to vex, nnoy or injure another person, ell we hold most dear; with- | or an intent to do awronginl ret, and aré estab, nt enforcement the law af. | lished eitl.er by proof or presumption of Inw. furds no protection; it is only by the punish- | Your power of judging of the effect of ey WAITING FOR THE RETURN OF THE JURY. Such being your duty, prescribed by | | mony, or that any alleged fact in the case is | in the case, | P’ such general principles of law asare applieable | of | that he has made at other times statements in- A.D. 1895,'in this | exist & union or joint operation of act and | lunatics or affected | ity, | w. H. T. DURRANT, CONVICTED OF THE PENALTY OF DEATH. MURDER OF BLANCHE LAMONT, WITH THE [Drawn from the latest photograph by Taber.] | dence s not arbitrary, but s tobe exercised with legal discretion and in subordination to | the rules of evidence. It is not a question. of number of witnesses. You are not bound to decide in conformity | { with the deciarations of any number of wit- | nesses which does not produce conviction in | your mind, agninst a less number, or against & | presumption of law or other evidence satisfy- ;fng our mind: in other words, it is not the | greater number of witnesses that should con- trol you where their testimouy is not satis- | factory to your minds, against a less numgber | whose testimony does satisfy your minds and roduces moral conviction that they are tell- | ing the truth. It is upon the quality of the testimony rather than the quantity, or the | number of witnesses, you should act, provid- | ing it produces in your mind this moral con- | viction and satisfies you of its truthfnlness. All witnesses are presumed§ tn speak the | truth. This presumption, however, may be | repelled and overcome by the manner in which | | t ¥ testify, by the nature and character of | | their testimony or by contradictory evidence. | A witness may be impeached by the part | against whom he is called by contradictory | evidence or by evidence that his general repu- | tation for truth, honesty or integrity is bad. A [ witness may also be impeached by evidence | consistent with his present testimony. | A witness willfully false in one partof his testimony is to be distrusted in others, and you may reject the whole or any part of the | testimony of any witness, if such there be in this case, who has willfully sworn falsely to | any material fact in the case. | All the presumptions of law in favor of innncence. | Al the presumptions of law, independent of | evidence, are in favor of innocence, and every person accused of crime is presumed to be in- nocent until his guilt is established to a moral certainty and beyond all reasonable doubt. This is a substantial right given by the law to | every person accused of crime, and this de- fendant is entitled to this presumption of in- nocence until your minds are convinced of his guilt beyond all reasonable doubt. You have observed that I haye just used the term “reasonable dount,” and I charge you that these words mean just what their fan- guage import. The term ‘“reasonable doubt” does not mean o mere possible doubt, a con- jectural doubt; nor does it mean a doubt which is merely capricious. It does not mean a mere speculaiive or possible doubt, having | | no warrant, no reason or foundation in fact, | because the issues dependent upon moral evi- | dence cannot be proved in many cases so that there cannot be some possible doubt, but it { means that the evidence must be such that it | will satisfy the mind, conscience and judgment | of thejuror, and satisiy him of the guilt of the i party to a’ moral certainty and beyond this reasonable doubt. Probably no criminal | chargo can be proved beyond the possibility of | & doubt or crror, or to a_perfcet certainty. Moral certainty is all the law requires to prove any fact. The prosecution must prove to this al certainty, and beyond this reasonable bt, all and every material fact and circum- stance upon which they rely for the conviction of the defendant. In the words of our own | Supreme Court, a “reasonable doubt” is that | staie of the case which, aiter an entire com- | parison and consideration of all the evidence, eaves the minds of the jury in that condition that they cannot say they feel an abiding con- viction {0 & moral certainty of the truth of the charge. The prosecigion not bound to prove gt The prosecution is not called upon or bound | to prove the guilt of any person accused of i crime to a demonstration, to_an absolute cer- | tainty and beyond the possibility of a doubt, for, as I have just stated, such evidence is i y, if ever, ‘attainable; as before stated, moral certainty of guiltisall that the law de- | mends, such cértainty as satisfies and directs i the mind of those that are bound to conscien- tiously act upon it. Our Supreme Court says that when the jury Is satisfied to a_moral | certainty and beyond a reasonable doubt that then they are entirely satisfied. A mere pre- ponderance of evidence against an accused | JATtY is not sufficient to warrant a conviction. | | The true medium, as I have just stated to you, { 1s that in order to warrant a conviction the evidence must satisfy vou to & moral certainty and bevond e reasonable doubt of the guilt of the defendant. A different rule, however, applies to a de- fendant accused of crime and on trial. A de- fendant may establish any fact necessary for bim to establish by a preponderance of evi- dence and is not obliged to establish such fact in his defense beyond a reasonable doubt. This means that any fact or proposition sought to be maintained and proved by the defendant may be established by a preponderance of evi- dence in his favor, that is, that the evidence in favor of the fact sought to be proved is in some slight degree greater and of more weight than that whicl is againstit. This rule is not applicable to the defense or question of alibi, &5 will hereafter be explained. As 1o the testimony of the defendant. The defendant has offered himself as a wit- Tess, and has testified in his own behalf. This { is his legal right, and you are not permitied under the iaw to discredit or reject his testi- mony simply on the ground that he is the ac- cused and on trial on a criminal charge. A defendant in & criminal case, testifying as @ witness in his own behaif, occupies a posi- : tion 1o the case different, perhaps, from that occupied by the other witnesses; and In con- | sidering the weight and cffect’ to be given to i his testimony s & witness you should notice 1 his manner upon the stand, his relation to the | case, the propability or improbability of his 1 testimoy taken in connection with all the other ey nce in the case; how far the same 1s supported or contradicted by other testi- mony in the case. You may aiso consider the consequences to him resulting from this trial; you should treat his testimony fairly, weigh it carefully and give it such weight and 'aredit as ¥ou believe it entitled to, These same tests, so far as they are applica- ble, and such others as may propor!!anxsest themselves to your mind you should apply to all the witnesses in the case in waisl‘nn‘ and determining the amount of credit and reliance you will give to their testiisony; and in view- ing and weighing the testimony of each and all of tne witnesses in the case you should con. | calculated to make & lasting impr, | reasonable doubt raised by the evidence, and sider thelr demeanor and manner upon the stand; their_interest in the result of this trial; how far their testimony appears consistent or | inconsistentin itself; how faritis contradicted, | if atall, by other facts and circumstances and testimony in the case; whether their recol- lection as to matters 10 which they testified is clear and distinct; whether or not there are contradictions and discrepancies on this trial from what they may have said and testified to | on other occasions, and if so, whether they are | of material matters, which would be likely to stamp themselves foreibly upon the mind of | the witness, or immaterial matters and circum- stances surrounding the transaction and not sion, Hon- est mistakes of memory in certain particulars may not be looked upon as evidence of false- 1oad, but where such exist the imperfection of the witness’ memory shouid be considered and taken into account in the examination of his | or her testimony, and give 1t, the testimony of | each of the witnesses, such weight as under all | the circumstances you believe it to be entitled | to. The motive of witnesses | to be considered. It is proper for you also in determining the | welght that you will give to the testimony of | the witnesses in the case to consider whether | or not any of the witnesses have anv interest | ornotive which would affeet their testimony | in any particular; whether or not by reason of their fniendship for, or hostility to, the de- fendant. thelr testimony has been affected or | colored; these and such other suggestions as | may fairly arise in your mind you should con- | sider in weighing the testimony of each and | all of the witnesses. The proof of a_chargein & criminal case in- volves the proof of two distinet propositions: First—That the crime charged was commit- ted, and Second—That it was committed by the per- son accused, and none other. These two propositions must be established by the prosecution to this moral certmnty and be- yond a reasonable doubt, as I have defined. The court clearly defines the law as to altdi. I am requested to give you in charge the law 8s to alibi, which simply means that the ac- | cused was at another place at the time of the commission of the crime, and therefore could not have committed it, and I instruct you that such a defense is as legitimate and proper as any other defense. All the evidence bearing upon this defense should be carefully consid- ered by you. If the testimony on this subject, considered with all the other evidence in the case, is suflicient to raise a reesonable doubt in your mind as to the gnilt of the defendant you should acquit him. The law does not require the accused to satisfy you as to his where- abouts every moment of the time necessary to cover the period when the offense is charged to have been committed. He is required to prove such a stafe of facts or circumstances as to create & reasonable doubt s to his presence at the place where and the time when the crime is al?egcd to have been committed, Entitled to the benefit i of a reasonable doubdt. The accused is entitled as much to the bene- fit of a reasonable doubt, as 1o whether he has or has not established his alibi, as to any other if its welght. alone, or added to that of any other, be suflicient to raise & reasonable doubt of his guilt, you should acquit him. The ques- tion for you to consider is, whether the theory of the prosecution against the defense of alibi is supported by the evidence beyond a reason- able doubt. The fact, if fact it be, thet an alibi was set up and maintained throughout the subsequent proceedings, should be taken into considera- tfon bv you in connection with all the evi- dence in the case in de‘ermining whethera | reasonable doubt of the defendant’s guilt has been raised. The accused is not required to | prove the defense of an alibi beyond a reason- | able doubt, or even by & preponderance of evi- dence; it i$ suflicient if the evidence upon that point raises a reasonable doubt of his presence at the time and place of the commission of the crime charged, and if e has done so, he is en- titled to an_ acquittal. The attempt of the ac- cused to prove an alibi does not shift the bur- de. of proof from the State. As to the personal identity of the accused. The question of the personal identification of the accused and his doings and whereabouts | on the 3d day of April last, the day on which it is claimed the deceased met her death, is of undoubied importance in this case. 1t may be taken as true that many persons arc and have been mistaken in the identity of others. The change in the appearance of the person whose identity is in question, the Want of perception and discrimination in the identitying wit- nesses and other causes have. probably, led to numerous cases of mistaken identity. "It may also be stated as a truth that persons are liable to be mistaken as to the identity of others, but whether they are so mistaken will probably depend upon’ the circumstances under which they claim to have seen such other person. The identity of persons by their appearance and close scrutiny may, in some cases, be far from satisfactory, certain or conclusive, and 1s often the mere opinion of the witness. Insuch cases the jury must form its own opinion; but if a_person has an object in noticing another, under perhaps peculiar circumstances, and his mind and eyes are attracted to the face, fea- tures and dress of such person, it will prob- ably be admitted that the chances of mistake in the identity of such person will not be as great as if he had no cause or reason for par- ticularly notfeing the person sought to be identified, and simply had & casual passing look or glance at him; of course, face, features. size, dress and general appearance and former acquaintanceship are important factors in the matter of identification. Itmay also depend, in a great measure, on the means of jdenti- fication which the identifying witness may have had; the clearness of vision of such wit- ness, the ‘time and place and all the circum- stances and surroundings under which the wit- ness claims to have seen the party sought to be identified. Eviaence oi ldentification shouid be as certain as human recollection will per- mit; caution and prudence should be used b ou’in considering this testimony. You wi ring to iis consideration your experience and good sense, and give to it such weight as it is entitled to. Weight of proof of good chardceer: When the proof adduced by the prosecution | You must consider and ragard. tends to overthrow the presumption of inno- cence with which the law clothes the accused, and to fix upon him the perpetration of the crime, the latter itted to support the | original presumption of innocence by proof of the fact that his personal character in the traits involved in the charge has previously been good, and evidence thereof is relevant to the question of guilty or not guilty. There- fore, you are instructed that the good charac- ter of the accused, if proved, is a circumstance His good char- acter, when proved, is itself a fact in the case. It is a circumstance tending in a greater or less degree 10 establish his innocence, and it is not to be put aside by yon in order to ascertain whether the other facts and circumstances considered by themselves do not establish his guilt beyond a reesonable doubt. Good char- acter, when proved, is to be kept in view by vou in all your deliberations, and by you con- idered in connection with all the other facts in the case, and if, aiter a consideration of all the evidence, including that bearing on the good character of the accused, you have & rea- ;‘(;xmhlc doubt of his guilt, you should acquit m, 1t is proper and legitimate on the part of the defense to lay before you evidence ol the good character of the accused, to induce you to be- lieve from the improbability that a person of £ood character should have committed such a crime as that with which the accused stands charged, and that there is some mistake or misapprehension in the evidence on the part of the prosecution, and in this connection you must consider it. There may be cases where good character in and of itself would create a reasonable doubt, when no doubt wonld exist but for such good character, and there may be cases so clearly proven.that no amount of good charecter would or should create such Teasonable doubt, Al sane criminals actuated by motive. It is undoubtedly a truism that all sane per- sons committing crime are actuated by some motive. Therefore, the presence or abscnce of any motive to commit the act of homicide, if homicide was committed as charged against this defendant, is a circumstance to be consid- ered by you in connection with all the evi- dence in the case. An accused person has the right to have every fact and circumstance in his favor weighed by the jury. Motive for the killing is an important essen- tial fact in the trial of murder, particularly so when the charge is sought to be maintained solely by circumstantial evidence. 1f upon a re- view of the whole evidence no motive is appar- entor can be fairly imputed to the accused in the commission of the erime charged against him,then thisis a circumstance in favorof inno- cence and should be so considered by you. The motive may not be apparent in many cases of homicide; there may be no motiye discerni- ble, except what arises at or near the time of the commission of the act, and yet the killing is not without a motive. It may be in many cases impossible to show or to establish affirm- atively a_motive, for the reason we cannot fathom the mind of the accused on trial and ascertain if there is not a hidden desire of ven- geance or some passion to be gratificd; be- sides, there is no rule of law which determines what'is or what is not an adequate motive even were it necessary to show one. Now, it is im- portant for the jury to determine, from all the evidence in the case, if any motive exists and appears in the present case on the part of the deiendant to commit the offense charged against him. You have heard various theories advanced by the respective counsel in the case, which they claim are based and founded upon the evidence, ana it is for you to determine from all the evidence in the case whether or notany motive existed for the commission of the crime (“si\nrgcd against the defendantby this informa- on. No limit to the 1inference of motive. With regard to the grounds from which mo- tive may be inferred, the law has never lim- ited them; therefore it is immaterial whether tne motive be hatred. wealth or the gratifica- tion of desires or passions, or arisiug from any other cause, 0 long as the motive exists. You must bear in mind that motive, being an auxiliary fact from which, it established in connection with other necessary facts, the main cr primary fact of guilt may be inferred, it may be established by circumstantial evi- dence, the same as any other fact in the case. 1f the motive of A‘P‘I\Hy in committing a erime has been delared by him, or direct evi- dence can be given of it by-the prosecution, then such proof wou'd be admissible, and might tend to the conviction of the accused; but the law does not require at the hands of the prosecution any direct afirmative proof of the motive of any person committing a crime, and one of the reasons for this rule, among others, is that the individual whose motive is sought to be ascertained may remain silent, or if he speaks and has & crime to conceal may speak untruly, and thus our minds are com- pelled from necessity to revert to the actual hysical manifestetions of the motive exhihited gy the results produced as the safest, if not the only proof of the motive. Thereiore, in deter- mining the question of presence or absence of motlve in the commission of a crime, it is in accordance with our general observation and experience to infer motive by reference 1o the laws which have been geuerally and usually found to control human conduct. This rule is based on sound reason and universal experi- ence. When a motive may be inferred. To illustrate this principle: If a man being of sane mind, and in the absence of asudden impulse, without any quarrel, or a word of explanation or warning, should draw his pis- tol, and take aim and deliberately fire its con- tents into the breast of another,and death should immcdiately follow such shooting, and upen hus arrest, and_ever after, he shouid re- fuse to give any explanation or excuse for his criminal act, upon the trial of such a man it is certainly clear that the prosecution would not be called upon to prove by affirmative testimony what motive, or that any motive, impelled the accused to commit such homicide, for the reason that the law will presume that he acted from motive, and that his actions were prompted by reason end were the result of causes acting upon his mind and deemed suflicient by him to inspire his action. The law of circumstantial evidence. 1 have been requested to charge ¥ou upon and it is eminently proper that I should give HD“ the rules of law upon that species of evi- ence called circumstatial evidence and ex- plain to you the difference between it and that :}weles called direct or positive evidence. Much hes been said of the nature of circum- stantial evidence and of the credit that ought to te given to it. Whatever may be the nature or quality of the evidence, if the mind isfully | satisfied we must act upon such conviction, altktough on acecount of the uncertainty of ali material affairs mistakes may be possible otherwise the business of the world must stand still. Tknow of no language more approprigte or better in explaining circumstantial evidence than that used by Chief Justice Shaw in the celebrated Webster trial, in which he lays down the correct rule as follows: Houw it differs from direct evidence. _The distinction, then, between direct and circumstantial evidence is this: Direct or positive evidence 1s when a witness can be called to testify to the precise fact which is the subject of the “issue in trial; that is, in & case of homicide, that the party the death of the deceased. fact to be proved. But suppose no person was present on the occasion of the death—and of course no one can be ealled to testify 10 it—is it wholly unsusceptible of legal proof? Ex- crience has shown that circumstantisl ev ence may be offered in such a case; that is, that a body of facts may be proved of so con: clusive a character s to werrant a firm beliet of the fact. It would be injurious to the best interests of avail in judicial proceedings. If it were neces- sary always to have positive evidence, now meny criminal acts committed in the com- munity, destructive of its peace and subver- sive ol its order and security, wouid go wholly undetected and unpunished ? The necessity, therefore, of resorting to cir- cumstantial evidence, if it ve a safe and reli- able proceeding, is obvious and absolute, Crimes are secret. Most men, conscious of criminal purposes and about thé execution of criminal acts, seek the security of secrecy and | darkness. Itis, therefore, necessary to use all other modes of evidence besides that of direct testimony, provided such_proofs may be relie on as leading to safe and satisfactory conclu- sions; and, thanks to a beneficent Providence, the laws of nature and the relations of things to each other are 80 linked and combined to- gether that a medium of proof is often fur- nished leading to inferences and conclusions a5 strong as those arising from direct testimony. No evidence is proof against accident. True it is that no witness has been produced here who saw the act of killing committed, and hence it is urged for the prisoner that the ey dence is only circumstantial and consequently entitled to an inferior degree of credit; this consequence does not necessarily follow. As before stated, cireumstantial evidence may be just as strong and convineing as direct evi- 'dence. A fact positively sworn to by a single eyewitness of blemished character may not be as satisfactorily proved as is a fact which is the necessary consequence of a chain of other facts sworn to by many witnesses of undoubted credibility. Innocent men may have been convicted and executed on circumstantial evidence, but inno- cent men may have been also convicted and executed on what s called positive evidence. What then? Such convictions are accidents which must be encountered. You will therefore understand that there are two classes or kinds of evidence which are used incourts in determining questions of fact, each of which is recognized by the law as legitimate | and proper evidence. An illustration or two muy here be proper to show you the difference between direct and circumstantial evidence. Ezamples of different kinds of evidence. If a witness should come upon the stand be- fore you and swear he saw another strike the fatal blow, by which his antagonist was killed, saw him stab him pistol and shoot him dead, all that you would Emve todo would be to judge of the truthit ness of his statement. If you believe such ness, there is no reasomng process to be carried on; your verdict would follow such testimon If youdid not believe him, you would reject h’ testimony and would not act upon it; but in a case of circumstantial evidence, where no wit- ness can testiiy directly to the fact to be proved, you arrive at it by a series of other facts, which, by experfence, will be found so associated with the fact in question as, in the relaiion of cause and effect, they lead to a sat- isfactory and certain conclusion. To illustrate this: When footprints are dis- covered after & recent snow it is certain that some animate being has passed over the snow since it fell, end from the form and number of the footprints it can be determined with equal certainty whether it was a man, a bird or & uadruped. Perhaps a better illustration is that if & witness testifies that a decensed person was shot with & pistol, and the wadding is found to be a part of a leiter addressed to the risoner, the residue of which is discovered in is pocket, here the facts themseives are directly attested and sworn to, but the ey dence thus offered is termed circumstantial evidence, and from these facts, if unexplained by the prisoner, the jury may or may not de- duce or infer or presume his guilt according to their satisfaction of the nature of tife connec- tion between similar facts and the guilt of the person thus connected with them. witness appears in court ana swears that he saw the fatal blow struck, or act done, whiech | deprived another of his life, the only question is, Does he swear to the truth? Does he commit perjury? Or is he mistaken in regard to the circumstances named? Circumstantial evidence as good as direct. When evidence is circumstantial it may be fust us satistactory ns direet evidence; as, for nstance, where a series of circumstatces are proved by many witnesses all tending to the same point, and when the circumstances are shown bevond all reasonable doubt, which lead neccssarily to one conclusion and are | reconcilable with each other, they may be as satisfactory as direct evidence, it is possible that &n injustice may be done. From the na- | ture of human tribunals, whether the evidence | be direct or circumstantial, in all cases there | is a possibility that perjury may be committed | or error occur. No human téstimony is su- rior to doubt; the machinery of criminal Fslice. like every other production of man, 8 necessarily imperfect, but you are not, therefore, to stop its wheels. Because a marn may have been scalded to death or torn to gieces by the bursting of & boiler or manglea v the wheels of & railroad car you are not to lay aside the steam engine. Indeed all evi- dence is more or less circumstantial, the dif- ference being only in the degree; and it is sui- ficient for the purpose when it excludes aisbe- lief and satisfies the mind to a moral certainty. The law exacts a conviction wherever there is legal evidence to show the guilt of the pris- oner beyond all reasonable doubt, and eircum- stantial evidence is legal evidence. this case I charge you that if the evidence con- vinces your mind beyvond all reasonable doubt that this defendant is guilty of the crime charged against him, then, although the prosecution has produced 1o eyewitness of the fact of killing, you should find him guilty. Each mode of proof has advantages. Each of these modes of proof has its advan- tages and disadvantages. Direct proof is enti- tled to great weight where the witnesses are | accused did cause | Whateyer may be | the kind or force of the evidence, this is’the | aciety if such proofs could not | d{ but | intelligent, honest and had a good opportunity to know the facts of which they testi; ¥ while, on the other hand, this direct prooi may be rendered worthless by mistake, interest or the perjury of the witness. Circumsiantial eyie dence has this great advantage, that various circumstances from various sources, all tend- ing to the same conclusion, are not likely to be fabricated. The principal disadvantage of | it is, that the inference drawn from the cir- | cumstances may be erroneous. The proper adminisiration ‘of justice renders a reliance upon circumstantial evidence necessary, for crimes seek concealment, and justice must re- sort to such evidence, or eriminals may go un- punished. It is, therefore, resorted to and relied upon; all that is necessary is that it should satisfy the mind of the jurors beyond all reasonable doubt. The rules that should govern you in the examination of this kind of eyidence are: 5 The rules of that kind of evidence. First—Each and all of the facts ana eircum. stances from which you would be' authorized toinfer the guilt of the aefendant musibe proved beyond all reasonable doubt; each material, independent fact or circumstance necessary to complete the chain or series of in- | dependent facts tending to establish_the guilt of ihe defendant should be established to the same degree of certainty as the main fact | which these independent circumstances taken together tend to establish; that is to say, each essentizl, independent fact in the chain or series of facts relied upon to establish the fact | of the guilt must be established to & moral | certainty and beyond a reasonable doubt, or you must acquit the defendant. | Second—The facts must be consistent with each other to make the chain of evidence come plete, and must all tend to the same conclu- sion, viz.: the guilt of the defendant. Third—They must a1l be consistent with the fact to be established, and must all tend to the seme conelusion, and be inconsistent with eny other reasonabie hypoth Therefore, when a criminal charge is sought to be proved and established by circumstantial evidence, the proof must be not only consistent with the prisoner’s guilt, but inconsistent with every oiher rational and reasonable hypothesis: each essential fact must be proved, they must be consistent with the conclusion to be arrived at, and not inconsistent with_each other, and they must establish the guilt of the accused beyond a reasonable doubt. Great care and caution should be used by you in drawing ine ferences from proved fac The Supreme Court on that subject. It is not sufficient that the circumstances proved coincide with, account for and there- fore render probable the hypothesis sought 1o be established by the prosecution, viz.: the guilt of the deferidant, but they must exclude | to a moral certainty every other hypothesis but | the simple one of guilt, or you must find the | defendant not guilty. In conclusion, on this subject I can use no better and more appropriate words than those approved by our own Supreme Court in tho case of The People vs. Morrow, in which the following language is There are two classes of evidence recognized and | admitted in courts of justice, upon either of which | juries may lawfully ‘find an accused guilty of crime. One is direct or positive testimony of an eyewitness to the commission of the crime, and the other Is proof by testimony of a chain of cir- s trong to the com- mission of the crime by the defendant and which is known as circumstantial evidence. Such evidence may <onsist of admissions by the defendant, plang | Iaid for the commission of the crime, such as put- | ting himself in position to commit ii: in short, any any acts, declarations or circumstances sdmitted tending to ¢ the acfendaot with There i3 nothing in e hat renders 5 of evidence. to_the heart, or presents | When & | And in | ely (o an absolute 10 a number of facts acts on which the guilt or inevitabiy follow. ¢ is superior to possible doubt and t I8 required, if under the forego- ing rulesthe testimony is suflicient to convince ¥0u, a8 reasonable men, 10 a moral certainty and beyond a reasonabl abt that the ndent committed the d in- th ormatiou, then I charge you it is your duty to convict. innocen No hur Cases recited by counsel to be | weighed. It frequently occurs in the trinl of criminal cases that the connsel for the defendant reads and reciles caseswherein it is clzimea that convietions have becn sought and had upon strong circumstances of guilt proved against the accused in_those cases, and afterward it has transpired that the accused was innocent notwithstanding the strong circumstances against him; and some like intimations we had in this case. These cases read and ed are extreme cases and probably oceur | very seldom in cases decided upon circum- stantial evidence, and if much search be mede it might be found that a greater number of | cases could be cited wherein improper con- | ions have been had from direct positive evidence through inattention or perjury of witnesses. All human testimony is iallible, but jurors in their decision mnst take and con’ sider cirenmstancgs and if sufficient act upon them, although the main factis proven by no | eyewitness. | “Tam requested by the defendant to charge | you,and I do charge you, that the mere. nsser: | tions of counsel are not evidence; butin con- sidering this case yon may look at and con- sider the theories advanced by the respective counsel claimed to be based upon the evidence and give them such weight as you think they are entitled to. Of course, you must act upon the evidence you have before you. | | From generalities to the case in hand. Heving thus given you in charge these gen- eral rules and principles of law that should | guide you in considering and weighing the ev- idence in the case, it becomes my duty to call your attention to the particular offense with the commission of which the defendant stands accused. As I understood the theory and claim_of the prosecution it is that the de- ceased, Blanche Lamont, met her death in the Emmanuel Baptist Church in this City and County during the afternoon of the 3d day of April fnstas the result of the unlawiul and felonious act of the aceused; and in order to convict the defendnnt of this charge you must be satisfied of the truth of this to a moral cer- tainty; therefore it becomes important for you to understand what constitutes the crime of murder and its essential elements. As before stated, the charge against the defendant, Wil liam Henry Theodore Durrant, 1s murder, and that cherge is specifically set forth in the in- formation which lins been read to you. Murder is defined by our Penal Code as the unlawful killing of & human being with malice | aforethought. Such malice may be expressed | or implied; it is expressed when therg is mani- i fested a deliberate intention unlawfully to | take away the life of a_fellow-creature. 1t is | implied when no considerable provocation appears, or when the circumstances attending the killing show an abandoned and maliznant heart. All murder which is perpetrated by means of poison, or lying in_ wait, torture, or | by any other kind of willful, deliberate and | premeditated killing, or whieh is committea | in the perpetration or atiempt to perpetiate arson, rape, robbery, burglary or mayhem, is murder of the first degree, and all otier kinds of murders are of the secona degree. In dividing murder into two degrees the Legislature intended to assign to the first, as deserving of greater punishment, all murders of u cruel and sggravated chardcter; and to the second ail other kinds of murder which are CAPTAIN I. W. LEES, THE MAN WHOSE DETECTIVE BRAIN DIRECTED THE GATHERING OF THE EVIDENCE ON WHICH DURRANT WAS CONVICTED.