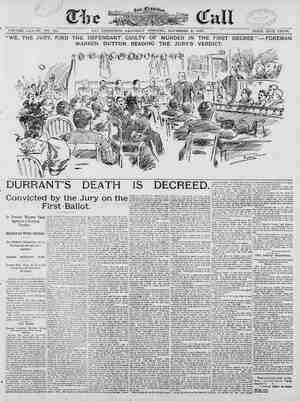

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, November 2, 1895, Page 1

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

VOLUME LXXVIIL—NO. 155. SAN FRANCISCO, SATURDAY MORNING, NOVEMBER 2 =ty 1895. PRICE FIVE CENTS. “WE, THE JURY, FIND DURRA THE DEFENDANT GUILTY OF MURDER WARREN DUTTON READING THE JURY’S VERDICT. %,L €. i | SUN Wil T A NT'S DEATH Convicted by the Jury on the First -Ballot. In Twenty Minutes They| Agree on a Hanging | Verdict. ; RECEIVED WITH CHEERS, The Mother's Despairing Shrick | Drowned by the Spectators’ Applause. BARNES' POWERFUL CLOSE. Durrant Talks About the Trial—His Counsel Says He Will Never Be Hanged. The jury yesterday found Theodore Dur- rant guilty of murder in the first degree. The verdict was reached on the first bal- Jot, and it was less than half an hour after Judge Murphy had . finished his charge that the jury was back in the box and the verdict was recorded. Judge Murphy will sentence Durrant to death next Friday. Durrant received the verdict stoically, | but his mother broke down utterly, and when her arms were around him and her tears were wetting his chaeks his stoicism deserted him and he showed at last some sign of feeling. The verdict was received by the crowd in the courtroom with a cheer that was quickly stopped by the court. e e THE WAIT. Twenty Dreadful Minutes While Durrant’s Fate Was Belng Settled. Durrant had borne up splendidly throughout the long trying day. And when the Judge had spoken the last words and the jury had passed out of the room they left him apparently as impassive and well-nerved as he has been at any time since he was brought back in his soldier uniform to answer for his crimes. His eyes were perhaps a little brighter than they had been and the effort to maintain his composure may have been more severe, but there was nothing in his mien to indi- cate it. He sat very still, chatting with his mother and with the few women who had gathered in a small circle around him. His very quietness was the strongest indi- cation of a strain. 1 do not know what they talked about, but asmile was often on Durrant’s lips,and sometimes the anxious faces of his friends mirrored the smile. It wasa grave smile, with nothing of the sneer which has been 80 noticeable abont the a smile as was on his lips earlier in the | day. When District Attorney Barnes was completing his speech in the morning Dur- rant sat like a man of stone, his eyes fixed extraordinary ' prisoner during his triai. It was not such | it scemed that every carefully worded sen- | have noted evi on the animated figure of the District At- | torney, his head supported on onre hand. He kept two fingers up against his cheek, the other two fingers being bent against his face and his thumb under his chin—an attitude of studious attention. For more than an hour he had preserved this posi- tion, saying no word and making no move- ment. He hardly seemed to wink. The rst time he changed was when the Dis- trict Attorney was smashing his alibi. Durrant bad testified that on the 3d of Avril he had gone on a long walk with a fellow-stndent. He had said that on that day he was not feeling well and did not feel that he would be able to eat a full | eal; so, instead of Junching, he boughta | etiul of nuts and munched them as he walked along. An exasperatingly long| cross-examination had followed. The trivial circumstance of the nuts engaged the time of the court for a long time, and everybody wondered why. | How much he had paid for the nuts? Whether he had paid for them with a | el, a dime or a quarter? What change | ‘z‘ he had received ? and adverbs. He never used one alone. The jury was charged to be fair, impartial, honest, unprejudiced, unbiased, unmoved by sympathy. All the law’s tautology was employed to tell the twelve men that they must do their simple duty and decide according to the law and the evidence. The spectators shifted uneasily when the Judge had been reading an hour or more. But Durrant still sat with his two fingers up against his cheek and his face telling mothing. In the midst of the Judge’s forensic lore a child in the rear of the room began to cry. A baby’s voice at such a time and in such a place was gro- tesque. Some of the women—and the courtroom was packed with them—snick- ered and giggled. The prisoner looked once toward the rear of the room and seemed as amused as the rest. The noise was soon stilled, and the audience, re- buked by the Judge, sank to silence again. But the smile lingered on Durrant's lips for sume time. It was over at last. The jury had the slips of paper on which were written the four fates, any one of which might be that of the prisoner's—death, life imprison- ment, long immurement, liberty. Dur- rant’s eyes followed the papers frem the Judge’s hand to the jury-box and re- What he had done with | | . ¥ nuts left at the end of his walk? | },vv?ry minute circumstance of the simple | incident was gone into, and the District | Attorney in argument read to the jury | mained there while the procession moved | all of this, and again everybody wondered | from the courtroom to the chamber where hy. | they were supposed to deliberate on their Then the District Attorney turned to | vardict. Everybody watched ~Durrant. the testimony of his companion in that | He did not withdraw his eyes until the walk, and showed that on the day when it | back of the last juryman 1n the line was really occurred Durrant and his friend | lost through the door. lunched together ata Fillmore-street res-| It is hard to say what his eves asked. taurant. And then the people knew why. | There certainly was not entreaty in them, It wasa lr:fl.o t a crushing one, and | or defiance either. It was not an air of when Barnes began to thunder and bring | not caring what happened and nobody the contradicting circumstances together | could read fear in his looks. . Durrant and everybody else realized that | On one side of him his mother’s glances | alm():jf, the last of the few poor points that | paralleled his own. For the first timedur- | rflmalnefl to the defense had been broken | ing the trial she dropped her air of confi- | down. Then it was that Durrant smiled. | dence and independence and if ever there | He mxnefl to his mothe: d spoke to her, | was dumb entreaty it was when this | and the llulc‘\vmm:x in black patted his | woman waiched the jury go out to decide hand and smiled back. Then Durrant re- | whether her son should live or die. The sumed his old stony pose and keptitalmost | poor, tired little mother frankly begged to the end—not quite to the end. for as the argument drew to a close the la. earnest and emphatic, and his ce rose in one of the few flights of eloquence in which he indulged. The summing up was strong—wickedly strong. Inafew words [the lawyer heaped the damning facts | against Durrant mountains high, and some of the thrill that all the other peonle | there felt must have penetrated the cold im- passiveness of the prisoner himself, for | | again be shifted, and again he spoke to his mother, and again he smiled. During the reading of the Judge’s charge the prisoner gave no sign. When Jmi;;e‘ | Murphy rolled out the long sentences in- | | Is and the paper bag. Whetner he the door long after the arbiters of her son’s fate had gone. On the other side of Dar- on his face. The mother hoped. The father seemed to know there was no room for hope. Durrant’s lawyer sat biting his mustache with the look of a man who knows be has done his utmost and that that utmost has not been enough. Usually when a jury retires from a courtroom there is a rush of the people to get out iuto the air and shake off the | strain. But the spell of the Durrant case was stronger than this inclination. The peopie did not leave the courtroom. A E | few moved around in order to see what mitted to do and what they were Dot per- | Durrant was doing, but most of them re- mitted to do, what they could take in de- | mained seated ; the women on the verge of ciding the case and what they must ignore, | hysterics; the men too interested even to | it seemed as if the Penal Code had been | talk. Three or four women, whose hearts wnitten precisely with the Durrant case in | had been touched by the loneliness of the | mind, E-.Ter.r sentenAoe of cold law sccx_nr«l l little group—father, mother and accused | to bear directly against the marble little | son—have during the last weeks of the imnn wli_xh the scowling face, who listened ‘ trial manifested their friendliness and so stolidly. The lawyers say it was a fair | sympathy by sitting with them day after and an able charge; that the law was|day. These and the Deputy Sheriffs clearly told and the prisoner’s right pre- | formed a hedge about the stricken family served. This may be so, but to the layman | to shield them from the eyes that would ery gulp of emotion and tence pushed the murderer a step nearer | every glance of terror. These ladies were the gallows. toa decply impressed with the solemnity of The Judge’s charge was very much of a | the time even to chat, as they chatted at literary effort. He heaped up adjectives | every previous interval of the case. A few | structing the jury what they were per- = %\\} “:fig\@ :%@MZ;):@» - O); | them and her eyes remained directed at | | rant sat his father, dumb misery written | ] ] IS DECREED., was all the comfort they could give. - Durrant knéw that there was an ordeal | coming when the jury went out—an ordeal the more dreadful to bear because he did not know whether it would last five min- utes, an hour, a day or several days. You could see him bracing up and straighten- ing his snoulders for his term on the rack, and when the torture actually began he was strong and able to bear it. | This waiting, unable to help or hinder, | while somewhere twelvé men are making | up their minds whether a human being | shali live or die is the climax of every murder trial. Many men have endured it | before that same Judge, but not one of them bore it as Durrant did. Isaw an- other young man, not as old as Durrant, | everybody else knew was his sentence to | death. He was an artist, who had mur- | dered his schoolgirl sweetheart, a man as | hot-blooded as Durrant is cold, as imagin- ative as Durrant is unimpressionable, as vicious as he, perhaps, but still human. And: there was something about his de- | meanor during this hideous hour that | came back as I watched Durrant. | There was the same air of sullen realiza- | tion of his powerlessness, the same deter- mination to shew no sign of fear or auffer- ing, the same endeavor to stare down any | pair of eyes whose too bold glances met | his own. Goldenson’s mother also sat be- | side her boy in his supreme hour. But | her recognition of the act that the rest of | the world counted her son as a devil who | must be removed from the face of the | earth was very different from that of the | birdlixe little woman who sat benind | Theodore Darrant in Judge Murphy’s | court yesterday. | Mrs. Durrant had apparently recovered from her breakdown of the day before, and as the minutes passed by her hope grew and she began to talk. Durrant answered her gently, but did not say a great deal. The women about her felt the hope com- municating to them, and she and they spoke brokenly together. The courtroom was deathly still, though the Judge was not upon_the bench and there was no visible restraint. When peo- | ple moved, they moved on tiptoe; when | they spoke, they spoke in whispers. There | were a hundred women and girlsin that | attendance where there should not have been one, for the strain was not one to which a woman should have been sub- jected. They had on their gayest dresses ana their prettiest bonnets, and the looks they cast on the hapless group were cold and curious. They had no business there. | It did not seem so bad when the lawyers | were talking, for the women had a right to | be intarested in the eloquence of the de- | bate for the murderer’s life. But when the talking was done and the ghastly business of the day was on, it was dreadful to think of these ladies waiting with the men to hear even Durrant’s doom. Most of them seemed to have some perception of the feeling. They were awed into unconscious- ness of each other’s finery. But curiosity kept them there until the last. Presently Durrant’s glances stole toward the clock. Hardly five minutes had passed cince the jury had gone out, but it must have seemed hours to him. He tried to join in the small talk that was going on about him, but the effort was too | much. The strain was telling, Gradually he became silent, and he slipped down into his chair until his head was pillowed upon the back and his eyes looked at the ceiling. Then his eyes closed and for sev- eral minutes he lay there asif asleep. And his mother, as silent as he, held his hund and looked with dry eyes at the empty jury-box.. The father sat like a man inadream. i People forgot all about the jury in their T i \% | | | words of comfortto the mother, an en-|interest in the silent, reclining figure. couraging pat to the son, a8 look of sym-| What did Durrant think? What dia his pathy and understanding for the fatherlmother think? Those who had sat in court from the beginning to the end of the | trial knew the force of the evidence that had been heaped up against the man. They remembered then the extraordinary statement of the veteran head of the police force, who said when he placed the charge of murder against Durrant that he had evidence enough to hang ten men. They knew the charge had been proven. They knew the defense had failed, and that the last hope of the Durrants, the erased roll of the medical college, was too light a thing to help him. Did Durrant know that when the jury came in it would only | be to name him for death? He, of course, knew the truth. Did the tearless mother and the ghost- | faced father still believe in their son's in- | wait nearly. an hour for what he and | nocence? There was no answer to these questions from the three unbabpy people who sat there so still. The boy remained with his eyes closed and his limbs relaxed. The mother stared at the empty jury-box. The father kept his eyes cast down in his misery. Every minute that passed meant a little more hope for Durrant. It wasnota case for argument in the jury-room and every- | body realized that if there was one man on that jary. who had not been convinced there would be no conviction. “If they stay out an hour they will stay out a week,” whispered a lawyer to a po- liceman. Duorrant heard the remark and opened his eyes and again looked at the clock. The jury had been out just twelve minutes. Thers was nothing yet on which to base a hope of a disagreement. Presently people beean to notice another figure a little apart from the group.’ Gen- eral Dikinson was as pale as his client. People had crowded about District Attor- ney Barnes when the jury was gome, to congratulate him on his speech and shake his hand. * They remained by him to talk and hear the congratulations of other men. Nobody went near Dickinson. They could not bid him hope that he was on the winning side or congratulate him upon the result of the trial. Except for the four women who hovered about the Durrants the prisoner had no friends in that courtroom. The people were waiting to hear him condemned to the gallows. When they snoke of the pos- sibility of a disagreement—the rpossibility of acquittal was not present in any mind there—they spoke as of a calamity. So Dickinson sat alone. There was an occa- sional word of sympathy for the attorney, for Dickinson is popular, and the people knew that there was neither fame nor fortune for him in his championship of Durrant. But no one came to whisper his sympathby into the ear of the attorney for the defense, Quarter of an hour had gone by, and Durrant shook himself together. He spoke a comforting word to his mother, and she pressed his hand. People began to move about a bit. In the slight bustle the dressmaker’s figure on which was draped the clothes of mur- déred Blanche Lamont was overthrown. 1t was caught before it crashed to the floor. Even this trifling incident stirred the assembly. The women shuddered and escorts hurried to bring a glass of water to their charges. Then again there was si- lence, and the ticking of the clock was audible all over the courtroom as the min- utes dragged by. The sun was in the west. Because of the glare only one window was clear to admit the light. Half of every face was in deep shadow. It was probably imagina- tion, due to the time and the surround- ings, that made this Rembrant effect seem 80 sinister. For five minutes more the courtroom re- mained in silence. Suddenly there was a whisper at the door. It rippled through the crowd of women, and where it passed it left scared faces. What they felt was coming had come. The whisper zig- | zagged across the room. It reached Dur- rant. He straightened up, bade his mother be brave, and waited. Every man and woman sought a seat, not too close to the defendant, and if possible our of the range of his eyes. The women particularly wanted to see how he took it, but they were afraid to gratify their desire. | The quick return of the jury could mean only one thing: There had been no dis- agreement. Not even one man -in’ the twelve had had doubt enough to need a moment's argument. | Durrant’s face hardened still more. His | high cheekbones seemed to stand out ;under the tightly drawn skin. His lips drew a trifle away from his teeth. The slight color that months of strain and im- prisonment had left vanished. There | seemed to be livid bars across his cheeks for an instant. Only hiseyes told ot no fear. The self-control of the man, which has been marveled at from the moment of his arrest, did not desert him. The Judge hurried back to the bench. Dickinson grasped a pencil. It was not even sharpened, and the movement | seemed simply mechanical. He felt he | ought to do somethirg and there was nothing to do. ¥ The court gave the order for the jury’s recall and after.a breathless wait, which | was really only a few seconds, the solemn | procession marched back. The twelve ! men came in like pallbearers at a funeral. They were pale and moved slowly, as men |do whe have performed a momentous duty. Durrant looked at each face as they passed him. The mother looked as hard as he. Tne father. gave one sweeping glance. Dickinson did not even turn. They took their seats and presently the voice-of the clerk broke the silence. It is an old formula they went through, but it never loses its impressiveness. “Gentlemen of the jury, have you agreed upon your verdict?” ““We have.” “Gentlemen of the jury, what is your verdict?” The white-haired foreman rose slowly, and slowly and steadily unrolled a paper he held in his hand. He read: *“We, the jury, find the defendant, Wil- liam Henry Theodore Durrant, guilty of | murder in the ficst degree.” The mother gave one cry, half moan, half shriek. It was the ery of one struck in the breast by a bullet. From down in the courtroom came an- other cry. It started to be a cheer. It came from all over the room. In anin- | stant deputy Sheriffs sprang up from everywhere and ordered silence. The | Judge on the bench thundered for silence and the cheer was throttled. It was an awful sound, that cut-off ‘cheer. The shrill voices of the women | were in it as well as the growl of the men. It was like the cry given by a pack of | hounds wheu they overtake their quarry. | It seemed thateverybody in the courtroom had joined in it, and when it was over nobody remembered uttering a sound or recalled that his neighbor had shouted. | It was the spontaneous exultation of the ! people,and really was not meant to be as cruel as it seemed. It was applause for the jury that had done its duty rather than a triumph over the wretch doomed to death. I wonder what Durrant felt and thought when he heard it? When the mother uttered her ery of anguish she lurched forward. Her son half sprang to meet her. They were locked in each other's arms; their cheeks were together and her lips sought his. The tears were coursing down the mother's cheeks and she rocked in her agony. The son tried to comfort her. He patted her gloved hand as she strained him to her bosom, and he tried to speak; but words would not come. The father, too, rested his hand upon her shouider. But there was no comfort for her. The women [ IN THE FIRST DEGREE ”-—FOREMAN | about cried with her, and still she clung to | her boy and shook with sobs. | Then people were ashamed of the yell of triumph with which they had welcomed the jury’s verdict. Men still shook hands on the doom of | Durrant, but forebore to look at the poor | mother. The women in the courtroom | hysterically wished they had not come, and at the same time watched the mother’s every convulsive clutch anda listened for every moan. The jury sat and saw it all. Pity for | the mother was plain on every face; but | not one man in that box would have changed his vote if he could. The shuddering stiliness was broken by the Judge on the bench giving notice that on next Friday he would set a day for sentence. *‘And, if the court please,” said District Attorney Barnes, “I would ask that on | that same day the trial of W. H. T. Dur- | rant for the murder of Minnie Williams ve | set.” | The cold, undistressed tone of the law- | yer with his legal business was grateful to | the overwrought spectators. The order was made as he desired, and the Sheriff’s men set about driving the people from the courtroom. They went at last and left the condemned boy still foided close in his mother’s embrace. ' CrARLES MICHELSON, S THE DREAD SEQUENCE. The Long Day Ends With a Mother’s Sobs—Durrant Would Have Made a Speech. This is the story of the day in court, told in detail chronologically. The usual jam in the morning; an extra force of po- licemen in the corridors; hundreds failing to gain admission. Inside not a vaeant seat as early as 9 o’clock in the morning; the aisles jammed and scores standing when at 10 o’clock the bailiff pounds his gavel and calls, ‘‘Hear, per Roll of the jury called; all answer, “Proceed, Mr. District Attorney,” from the white-haired Judge on the beach. “The Minister of Justice'’ rises and faces the jury, looking every inch the ap- pellation first bestowed upon him by him- self, but now te cling to him till the end of his career as District Attorney. He goes at once to his task, conscious that he has talked longer than he prom- ised; conscious, also, of not having cov- ered more than two-thirds of the points in the case, and desirous to leave no point undissected—undiscussed. The prisoner sat as usual, calm and im- perturbable. His mother, that little woman in shining black behind him, not as restless as she used to be, not as smiling and as confident as she wasa week ago, but also calm and outwardiy composed. The father sat at the end of the row of chairs behind the prisoner. Throughout the whole day he gave no sign. His is the woe that feeds on the vitals, finds no sur- cease but time, is uncomplaining, un- demonstrative. All morning the “Minister of Justice” talked, save for the brief recess that was taken at 11 o’clock. His flights of oratory were few and far between. He had now | something of vastly more importance to do. The trial must end with the day. He felt that. Everybody in the room feltit. 8o be must hasten on with the argument, pausing only an instant here and there to robe a passing thought with the white and sparkiing pearis of speech that fall so readily from his lips. | He dealt with the defense of Durrant, touching it not entirely, but touching it with master strokes of logic and lucidity Were your last cards, invita- tions, announcements, Jbadly engraved ? ) Crockers’ didn’t do them. 227 Post. street 215 Bush street