The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, November 2, 1895, Page 2

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

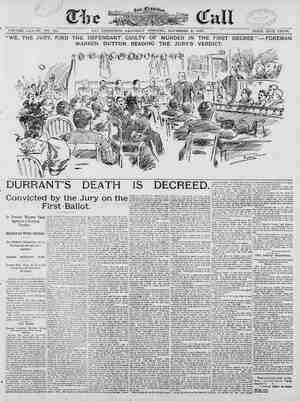

THE SA wherever his heavy hands fell upon it. He tore the {r: structure into shreds, and there stood Durrant “amid the wreck of his own defense.” But Durrant heeded it not. mmoved, but not i 3 After the bricf recess came the perora- tion. It was a disappointment to the gal- lery, but it proved that Mr. Barnes has wisdom sas well as eloquence. He could have done no wiser thing than he did. The time for embellishment was over. In a few hours the jury wouid decide the fate If there was still a lurk- any juror’s mind— equent events proved that there the District Attorn: him, in the jury mind, tl ¢ rather than of eloquence. comparatively quiet and unostentatious closing periods Mr. Barnes displayed something that is rarer dom, which js good taste. 3arnes’ exposition of the rements of gas, which he illus- ral large pasteboard boxes, on made several objections to Judge Murphy overruled these after Mr. Barnes explained that the boxes offered us exhibits, but merely as s remarks. the conclusion of the perora- me the court’s customary admon- isiment of the jury, delivered with more solemnity this time than ever befo; it was the last time. It was half- o’clock now, half an hour hour for the Others were place ¢ logi ted other magic own only to his own understand- women in the room turned their he doc tantly. *‘Pass and they re- fore the courtroom ba ed. afternoon crowded corridor: himsel in. and all p nd im tely outside the courtroom conducted with decorum and with an added air of The earliest comers found the prisoner seated in his usual ce, but Mr. and Mrs. Dur- rant did nof rive till w n half an hour of the convening time, Jud furpl four minutes late. minutes, seconds, now stood o like er time. Judge Belcher 1dge Murphy, and the lat- r beside the court on the r of Justice” occu- tiorm to the right of uadow of the model epochs walked behinc ter took a be The pied a seat on the the beach and in of the belfry t > gown and amont. Perched high rney wers two busy ileged spec- ound the District che La Judges, stood or sa ow per- table, ft of Judge s and Judges and of- newspaper men and of the bar, Mrs. ter has heard all of brilliant speech, and s been uenc: an @ ela d to the the attor- said—or the few Chat is M 2, the And the was that Mrs, s motk t couid not see the silent woe of that other mother and forego word of human sympathy. At the noon she stopped a moment when passi Durrant, took the little black-eyed 1’s palm in bers and whispered a word of sympathy to the other woman. But all this, of course, is quite irregular. It happened aiter the adjournment and vy has no place in a matter-of-fact record of this impressive and formal ses- sion of of the Superior Court of San of California against William Henry The- odore Durrant, ss. The bailiffs rap for order, “Call the jury, Mr. Clerk,” court. “Thomas W. Seiberlich,” reads the clerk from his big roll-book. “Here,” answers the juror. says the “Natban Crocker.” SHere “David Brooks.” Here.”" “Frank P. Hooper.” “Here.” “Horace Smythe.” “Here “Louis Gregoire,” ‘d “Here. “M. R. Dempster.” ‘‘Here. ‘“Samuel E. Dutton.” *Here.” “John H. Bartlett.” “Here.” “‘Charles P. Nathan.” “Here.” “Warren Dutton.” ““Here.” ““All here, vour Honor,” says the clerk, and the big black book closes over the names of these twelve good men and true, o be opened but once more. And while the jurors ace answering to their names those who look ahove the last row ot jurors see dangling from the row of hat pegs seversal overcoats. The day is warm aud pleasant. There have been cold and foegy days since the trial began last July—and no overcoats on those pegs. Does the presence of these great coats portend anything? If they do, what is ii? Do the six coats mean that there are six men in that box with their minds made up so firmly that they come prepared for an all-night seance if need be rather than join in a verdict contrary to their judgment? And. if.they mean this in which way are these minds set? You can see by Mre. Durrant's face that she is still hopeful. You can see hope as well as anxiety on the father'sface. You can see on the prisoner’s face—nothing. Judge Murphy adjusts his spectacles. A pitcher of water is passed to him. He moistens his lips from the glass. How stern and frowning he is. He looks up from the pile of .typewritten folios before him, and is in the act of— But it is Mr. Dickinson who speaks first. Heis on his feet. He speaks slowly and solemnly and more formally than usual, “If your Honor please, I desire at this time to take exception to certain remarks made by the District Attorney this morn- ing,” he says. I refer to those parts wherein he denounced the defendant and spoke in a manner to arouse the pubiic sentiment.” Judge Murphy doffs hLis spectacles and turns from the typewritten folio. The audience is breathless, hungry for a storm that seems to' portend from the Judge's eyes. “‘General Dickinson, if the District At- 0 in the case of the people | torney had been guilty of an impropriety during the course of his remarks it was the duty of counsel to cail the attention of the court to it at the time. The court is'not now aware that the District Attorney over- stepped the bounds in any sense, and at all events this objection comes at rathera late hour.” “Nevertheless, your Honor, we desire—"" persisted Mr. Dickinson, in a voice scarcely audible. *‘The court has heard enough on the sub- ject,” said the court. And then the court replaced its spectacles and turned to the folios. “I desire to take exception to the re- marks of the court, if it please your Honor.” This from Dickinson, still per- sisting—having the last word, as the rec- ord will show a hunared years hence. Now the court takes up the first folio. The court’s chair is pulled forward a trifle and the court itself leans partly over on the bench and begins to read the court’s charge to the jury. There are forty-three of these folios 1n front of the court, and there are nearly or guite 200 words on each page. It is now seven minutes past 2 | o’clock. The reporters figure out with their pen- cils how long it will take for the court to reach that last page. They allow him 180 words a minute, and they send “copy” down to the evening papers that “the jury retired at 3:15 o’clock”—which, of course, it didn’t. Now Durrant turns to the jury and tried to read his fate in their set, determined, attentive faces. The father also looks at the jurv. The mother—she looks at her | boy. She will read in his eyes the mean- | ing that he may find in the juror’s faces. Judge Murphy is ata disadvantage when | reading, especially now when the light is | bad and the tension of all strained. He is | used to these scenes, hardened in a way and secured against the grip they have on laymen’s hearts and sympathies. Yet a man cannot be very different from his en- vironment, and if the whole truth could be told there is probably an increased thumping of the judicial heart at this eriti cal hour, and may be that is why he some- | times lost his place in the manuscript, | and must repeat a word here and there to give it the inflection it deserves. Then the jndicial lips grew parched at times. Once there was an unseemly noise in the rear end of the room and oncea baby cried outrignt. All these things the | afternoon newspaper men could not fore- see when they wrote at 2 o’clock that “the v retired at 3:15,” and they all caused s. The last one—the incident of the ving babe—caused the longest delay. People were astonished when they heard that strangely incongruous sound in this solemn assemblage. *“There’s a mother that ought to have better sense,” people whispered to one another, as the judicial reading halted and the judicial eyebrows were elevated. And they said a good many harsher things than that about this foolish woman who brought a babe in denouement of a murder trial. ailiffs woman with a babe in her arms were also roundly criticized. The atmosphere w | within the room. So much was a physical fact. It wasalsoreeking with the air of tragedy and sensationalism; but this psychological, and the mother and the | bailiff could be excused for ignorance on | this score. But what an atmosphere for an innocent mite of humanity to breathe! Here is contrast enough for a Zol pen. voice of a child ecrying out at the phantom of the hangman! Maybe those tiny, bright eyes just over from the nether world could see plainer the grim wraith hovering over the prisoner’s chair—or was it the fetid air that made the babe whine? Some of the women that always sit near Durrant are reading the s pavers—reading how the jury retired 3:15. Noble and Maud Lamont listen at- tentively to the court’s reading, though in the nature of things they do mnot under- stand it. Un the same rowis a woman with a yellow chrysanthemum screaming | from the background of a shiny black silk | Bhe is looking the other way— ard those well-dressed young ladies ly opposite, who are chatting, about the next theater party. r the men’s faces are the most seri- in the room, as they are also in the minority. rtain Lees drinks in every word that falls from the judicial mustache. Now the Judge reads that Durrant’s testimony must not be discredited simply because he is the defendant. Captain Lees looks nervous now. He leans forward keenly and a shade of annoyance is on his face plainly. leaving the court. Of course, her leaving caused another flutter in the crowded room. “Gentlemen, do not leave your minds be distracted from this solemn duty by any exterior circumstance,” says the court. Then the court proceeds with the reading. He reads clearly. You can hear every word. Lawyers in the room look wise and whisper that it is an admirable docu- ment. It is now 3 o'clock. The court has reached that point of his charge where he deals with circumstantial evidence. He says that footprints in the snow would be circumstantial evidence, and yet better evidence that some one had walked there than would be the oaths of a dozen men who saw the person walking. A man at the reporters’ table leans over to say that the same illustration was used by Judge McConnell when he charged the Cronin jury in Chicago five years ago, and then another man adds that from time im- memorial all Judges have used this illus- tration because of its aptness. It is 25 minutes past 3o’ciock now, and the judicial reading has reached the point where “the jury has no option in the ques- tion of degree,” and ‘‘the time between the motive and the act may be as instan- taneousas the thoughts of the mind.” It sounds as though it were near the end, but those who can see the bench clearly know there are several pages still unread. Five minutes is a long time now. There are sundry coughs and sneezings in the room. The bailiff lowers the cur- tain on the front window to the left of the court, disclosing Durrant in the act of ex- changing whispers with his mother. He smiles as he looks back again to the jury. In the gray light his features look a bit drawn, as though the strain was telling— but perhaps it is only the peculiar, ghost- lige properiies of the light. Certainly he does not look pale and haggard as he did when he appeared between those folding doors in the infant-room before George King. Now the court reads that the jury may, however, take into consideration the in- terests which the defendant has at stake in judging his testimony. Captain Lees’ face resumes its composure, and he sits back in his chair and goes on chewing that same quid of fine cut. Captain Lees hasa face that artlists delight to draw—but it's not a preity one, It is 29 minutes past 3 o’clock, and the court reads, “My task is done and your solemn duty begins.” Even the screaming yellow chrysanthemum now arms into the | And the | nd Under Sheriffs who admitted a | | standing there at the side of his bench. By and by the mother is shamed into | | FRANCISCO CALL, SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 1%95 AN N St o R e = & = HON. D. J. MURPHY, JUDG OF THE SUPERIOR COURT, WHO PRESIDED AT THE TRIAL OF DURRANT. [Sketehed from life by a ¢ Call”? artist.] turns toward the court and the listening jurors. Had the court whispered the rest every syllable would have been caught. ‘‘Du { well performed its own best reward,” are | the last words of the charge. | Now the court rises and tells the jury to retire for deliberation. Four blank ver- dict forms are handed down to Juror Dut- ton, one of them for murder in the first degree, one for murder in the first degr fixing the penalty at death or life impris- onmert, one for murder in the second de- gree, ong for acquittal. From which shall the foreman read when the jury returns? | “Mr. Clerk, swear the bailiffs to take charge of the jury,” says the court, Bailiffs Rock and O’Connor step for- | ward—one a very tall man, with.a dark mustache; one a man not at all tatl, with a “red’’ mustache. ‘While this is being done the “minister of justice” comes out from the back- ground a bit. | “If your Homor please,” says Mr. | Barnes, “I am informed that the Grand | Jury has offered the use of itsrooms to this | jury.” *Very well; Mr. Bailiff, notify the | Grand Jury that this jury is now ready to retire,” says the court. “The Grand Jury has already vacated, | your Honor,” comes the answer. | *“Now, gentlemen, you will retire,” says | the court. * | ‘“‘Make way there for the jury,” shouts | the bailiff as the jurors begin to pierce the | great crowd. “*Mr. Sheriff, keep that passageway open for the jurors,” thunders the court. But Sheriff Whelan himself is already in | ill\e foreground and has managed things { skillfully. The jury passes out silently. | They take their greatcoats with them. Does that portend anything? Their faces are very solemn, but they walk with much | the same tread as they did when they en- tered the room at 2 o’clock, albeit more slowly. How differently they shall enter the room for the last time! But that is not known now. Durrant tries to fathom it—perhaps he does, as he | watches closely each set and determined face as it passes by. Now they are gone and there is disorder in the room. , Many leave, thinking surely i there will be no verdict for many hours. These have not heard the testimony. Others leave because they have seen and heard enough. The greaily lessened crowd breaks up into little groups. 'The afternoon paper men fly to the telephones and try to catch the last editions to change that3:15 to 3:33. The men go out in the corridor and smoke. Mrs. Durrant talks with Theodore and with the women who surround him, Mr. Durrant is pacing the corridor, gathering calmness for the end that is to come, it may be, from the blue smoke of a white cigarette, General Dickinson remains in court and talks with the defendant. Sometimes in the conversation the defendant accom- panies his words with a smile. Some policemen come in and take out the pasteboard boxes that the minister of justice used to illustrate his theory about the gas. That leaves a larger open space in front of the jury-box. Ten, fifteen minutes have gone by. Mr. Durrant returns. The defendant watches the outer door for the return of the jury. He alone seems to expect a speedy verdict. At 5 minutes to 4 o’clock a man enters the room and says: “They have agreed!” Durrant hears it, but gives no sign. Others who hear it wonder if the man | knows what he is talking about, or whether tnis is only a chance remark. Then another man enters and confirms the news. Those in the corridors have known it for a whole minute. Judee Murphy is seen entering the door. The bailiff raps sharply for order. No need of that. A hush falls as quickly as a shooting star, so quickly that the men {orget their hats. Judge Murphy takes his seat. ‘“Hats off, court’s in session.” says the bailiff. “‘See that the people sit down and keep out of the passageway,” says the court. “Now, Mr. Bailiff, go to the jury-room and see if the jury has agreed upon a verdict. If so, bring it in.” Mrs. Darrant’s friend, the lady in fawn- colored gown, takes a seat at the other side of Durrant, leaving him between her and his mother. Durrant leans back com- {fortably in his chair. Mr. Barnes, Captain Lees and all the other officials enter. Then the jury. How solemnly they walk now. to read their faces. You can see it in their You can feel it in the atmosphere. . Durrant bends her head low toward ber son, but nevertheless watches the | twelve grim men as they Behind them come Mr. Lord Dundreary limp Peixotto and his Curious that one | should notice the peculiarity of this limp at such a time. The crowd closes up and presses forward. The Judge is on his feet. “Stand back | there!” he roars savagely, and this relieves | tbe tension somewhat. *“Mr. Clerk, call the jury.” Thi=isdone. The ‘‘heres” are firm but aimost inaudible. The clerk kuows his part. e does notanswer *‘All here, your Honor,” as he has done twice a day and more since the 22d of July. What he says is this: ‘‘Gentlemen of the jury, have you agreed upon a verdict?” “We have.” voice. ‘“What is your verdiet?”” Warren Dutton,” standing there at the corner of the jury-box, opens a bit of pa- per and spreads it out. How long it takes bhim. How long, how slow he is, how—. But he is reading now. The words fall: ““We, the jury, find the defendant guilty of murder in the first degree!’” There is a wild, convulsive sob from the mother. Durrant straightens himself quickly and leans forward to Mr. Dickinson: then makes as though about to rise. “Let me make a speech,” he says to Dickinson. Then his mother's arms are about his neck and he could not rise to speak even 1f Mr. Dickinson had not whispered: *No; keep quiet now!"” A shout goes up from the far end of the room—from all parts of it; a shout of ap- proval; a shout like that of which 8 pack of hungry wolves vent themselves when the prey is cornered. “Silence!!” came in thundering tones from the court. Then the crowd felt abashed and only the mother’s sobs could be heard. “Gentlemen of the jury, I feel that you are entitled to the thanks of the entire community for the conscientious manner in which you have performed your duty,” said the court, and then this, aiter consult- ing the calenda *1 will fix Friday, November the 8th, as the day of sentence—one week from to- day—and until that time the prisoner is remanded to the custody of the Sheriff.” Agsin Mr. Barnescomes out of the back- ground. ‘'1 ask your Honor to also put down the case of the people against Durrant in the Minnie Williams case,’” he says. “That case will be called then and set for trial,’”” says the court. Then he adds: ‘“The court now stands adjourned.” Three Deputy Sheriffs stand close in about the women who surround Durrant, the mother still weeping in his arms. Her sobs are no longer audible. Allthe women in that group are weeping. It is left for Mr. Dickinson and Durrant to comfort them. “‘Step right outside please, step right on, please,” call the bailiffs asthe crowd lin- gers. Mr. Dickinson is deeply moved by the scene about him. Presently he leaves it and goes away. By this time more than half the people have gone out and the hailiffs are urging the others to use speed in leaving. Itis quarter past 4 o’'clock when the courtroom is finally cleared of all but the bailiffs and Under-Sheriffs, a few news- paper men and that group of weeping women. : The newspaper men exchange notes, with the result that all learn the jury was out just twenty-eight minutesand that the verdict was agreed upon at the first ballot. Now a bailiff approaches Durrant and lays his hand on the prisoner’s shoulder. “What do you want?’ asks Durrant. He is far less affected than the big-hearted bailiff beside him, who looks as though he were biting his tongue to keep back the tears. But Durrant must go. He walks out boldly, bravely, upright, unialteringly, two Under-Sheriffs in front It is Warren Dutton’s No need | e into the box. | |of him and three big policemen behind | him. | There is only left the mother and the | father and thres lady friends. The mother is weeping still. Presently she dries her eyes, but never the woe at her heart. She stands up bravely, and Mr. Durrant fastens hercape at the chin. Then | all go out. | The day’s work is done 1 T AT i THE SILENT BALLOT. | How the Jury With No Word of Discussion Chose Its Verdict. % | The jury retired to the rooms which were set apart for the use of the Grand Jury just across the ballway from the courtroom. The long months of listening to evidence,'the davs of being talked to by the lawyers and advised by the. Judge, were at an end. The time had come for them to'act—to express their judgment on it all. They had heard enough; they did hot care to talk about it—to ask an opinion one of the other. They were ready toact; it was simply a matter of how—the form of it. They had had no occasion before to organ- ize. 1. J. Truman proposed that ¥~ -an Dut- | ton be chosen foreman. By co: unsent the proposal was acceptea : uey sat down to do what they had to uo in form, no man knowing what that thing they had to do was further than that in his own mind he had determined to write “‘guilty” upon the ballot that might be handed to him. Mr. Truman proposed that they proceed at once to ballot and likewise this was con- sented to with no word of discussion. It was a matter of few moments. Each juror wrote privately his judgment upon the little slip of paper, folded it up and dropped it into the receptacle provided. Mr. Dutton was requested to read the ballots—what was written upon them. Stepping to the center of the silent, somber-faced little group he picked them out one by one and read them: “Guilty.” “Guilty. “Guilty. “Guilty.” “Guilty.” “Guilty.” “Guilty.” “Guilty.” “Guilty.” “Guilty.” Twelve of them—*‘guilty” every one. Even this called for no comment. Tru- man walked half across the room and back again and took his seat. “Let us now vote upon the degree, Mr. Foreman,” he said. Quietly the ballots were prepared. There was no hesitation, no suggestion of doubt, no word spoken beyond what was absolutely necessary to the transaction of their unhappy business. Again the ballots fell into the receptacle and again by a nod from Truman Mr, Dutton picked them out and read the death sentence in the twelve times repeated ““first degree.’” It was finished. The twelve men rose up and silently crossed the gloomy hall- way again back into the thronged court- room, where tothe waiting ‘multitude the solemn procession of ‘their quiet return told the story before they spoke it. ”» HOW THE NEWS SPREAD. Crowds in Front of the City Hall Waliting to See' Durrant—No More Luxuries. The news of the verdict.spread more rapidly than did ever a prairie fire fanned by a raging gale. Within ten minutes from the time Warren Dutton read the jury’s findings it was known to more than one-half the inhabitants of San Francisco, so keen was the interest of the public in the great trial. Every telephone in the new City Hall was tinkling for a switch at the central telephone station. Almost in- stantly the verdict was &nown and each one conveyed the news to the listener at the other end. Other switches followed in quick succession, and thus the result of the trial became known all over the City even before the crowd had dispersed from the courtroom. £ The news had also been passed about in the streets between the reading of the verdict and the time the prisoner was taken from the City Hail, and a thousand or more people had gathered about the Park- avenue and Larkin-street driveway frantic with curiosity to get a glimpse of the con- demned man. But they were all disap- vointed, for a Jarge force of police kept the crowd back and the prisoner was hurriedly rushed into the van and driven rapidly away. There was no demonstration on the part of the crowd other than curiositv. Three deputy Sheriffs rode inside the van with Durrant, and as many more as could crowd on the seat and steps on the outside were sent along asa precautionary measure. At the County Jail there was a wild scene. Broadway was for half a block either way from the jail blocked with peo- ple when the van arrived, and Sergeant Conboy, who was there in charge of a squad of police, had to telephone to Cap- tain ‘Whitman for twenty extra men to keep the mob back, albeit there was no at- tempt at any overt act. Like the crowd at the City Hall the peuple were agog with curiosity. Once safely landed inside the County Jail Durrant was no longer a privileged character, as he has been called by the other prisoners there who have not taken kindly to the idea of his being so much more comfortably quartered than they. Previous to the jury’s verdict he had, under the assumption of innocence, been permitted to be made comfortable by his people. He had a soft cot, a coal-oil lamp and a table to set it on and upon which he might do his writing. He had a large shelf well stowed with good literature, and in fact, barring the narrowness of tife cell and the confinement imposed, he was as well off as he would have been in his own home. Durrant did not return yesterday to his comfortable quarters. A jury had pro- nounced him guiity of murder and he was a common felon, and being no longer enti- tled to the assumption of innocence could no longer expect to_enjoy privileges other prisoners are denied. He was taken to the reception-room and siripped and bis clothes carefully searched by Jailor Satler. ‘When dressed once more he was placed in cell 27, along with Forger Sargent, no longer to be an object of envy of the other prisoners, for he must now partake of the same plain fare and sleep on the same sort of bunk that is provided the poorest among the prisoners. His parents will not be hereafter permitted to carry him delica- cies or, in fact, do any of the things that have made his life in jail a pleasure rather that a hardshi C R S BT MR. BARNES’ PERORATION. A Fitting End to the Most Dramatic Legal Battle of the Cen-~ tury. ‘When court opened in the morning Mr. Barnes resumed his argument. Thursday evening he had reached the end of his an- alysis of the State’s main case. He now took up the testimony that has been of- fered for the defense. We are led naturally and logically now toa discussion of the defense set up by this de- fendant, he began. I want to commence with the first and main element of that defense— the alibi. 1 shall consider the alibi first in_its general application, as a refuge for all mur- derers and larcenist$ unless they are caught red-handed in the act; and, secondly, with reference to this particular alibi set up by this particular defendant. Dr. Cheney's testimony amounts to only a belief. Mr. Barnes now read several extracts out of legal sheepskin, all of them bearing on the general aspect of the alibi in criminal jurisprudence, Then he turned to the promises made by Mr. Deuprey in his opening: 2 We were promised, he began, that this de- fendant would teil us in his own plain and simple words the events of ithat 3d of April. He would tell us that he attended Dr. Chenc{'s e by lecture that afternoon—which he has; and would be corroborated by the rollcall and Dr. Cheney. Now, what does Dr. C timony amount to?—to mere! b correctness of hisrolleall. Aud they ask you, upon the gauzy texture of such an alibi as this, to lock up in the limbo of unbelief all of the testimony of the people! Gentlemen, 1f this defendant has not told the whole truth he stands amid the wreck of his own belief a condemned and guilty man, The defendant’s story is all true or it 15 all false— youhave a lehl to so consider it, and I believe the court will so instruct you. The events of another day have been transposed. I claim that this whole defense is a fabrica- tion and a lie, and in doing this I wish especially to exempt General Dick- inson and Mr. Deuprey from -any eriti- cism I may make upon this defense. They have conducted their case ably and con- scientiously. But they have had to make a de- fense and they have had to take the case as furnished to “them by their client. What is that defense? It is this: The events of an- other day have been transposed to this 8d of April. Students Carter and Ross told you ithe truth. Carter did walk with this defendant; Ross did meet them walking. But, gentlemen, neither of them fixes the date. Who does fix it? This defendant. Out of the mouth of his own witnesses has this defendant shattered and scattered the fabric of the alibi he had so carefully reared. I could never have attacked it so successfully as he has done. He has been working on historical parallels—repeating the history of every great criminal, condemning himself out of his own defense. Gentlemen, with a genuine rollcall why should this col- lateral testimony be necessary? Carter and Ross pass into the golden book. When the defendant introduced the testi- mony of Rossand Carter he overstepped the line between demonstrable truth and de- monstrable falsehood. Ross and Carter, in- stead of corroborating the defendant, have contradicted him. It was not on the 3d of April that they were with. Durrant—they did notsay it was. Ross and Carter have passed into the same golden book as Mrs. Vogel, Miss Edwards, Mrs. Crossett, Mrs. Leak and all the others. And now, gentlemen, we come— to—the rollcall. Will you let me have it, Mr. Clerk? The book in question was passed over to the District Attorney, along with a couple of magnifying-glasses. Mr. Barnes laid them together in front of the jurors and asked them to examine carelu]iy the erasure after the name of Durrant. He discussed the imperfections of the rollcall then, and the manner in which it was kept, and at the end of this vivisection he called it “the weakest plank he had ever seen to stand between acquittal ame;fl by alibi and a righteous convic- ion. Mr. Barnes illustrates the measurements of cubic fect. The District Attorney then followed the statement of Durrant, who says he left the college after Dr. Cheney’s lecture and went to the church to fix the sunburners, arriv- ing there at five minutes to 5 o’clock. The agenker stopped a moment to_dilate upon the strange and unfortunate (for Durrant) fact that he went along all_the route from the college at Clay and Webster streets way out to the Mission, which was the de- fendant’s home, without being seen by any living witness. Then he went with Dur- rant into the church. He tells us that he took out his wateh when he went ix.to the ){brary-room and laid it aside. Why did he do this? To keep it from falling out’of his pockét while he was fixing the gas. Whatdid that mean? It meant that thisde- fendant’s head was to'be lower than his heels at some time. show you the dia- gram Durrant himself has-drawn to show you his position when . fixing the gas- jet of the sunburner.. What does all this irresistiblylead to? Itleads to this fact— that when the head is lowered like that there is a rush of blood forward. That is a simple fact. Hold your head down for half & minute —instead of three or five minutes—and your face is red and-flushed. Couple this fact with the fact that science tells you that gas ‘inkala- tion turns the blood red end gives the flesh a flushed appearance, and then consider that this defendant, out of his own mouth and from his own witness, tells you that he appeared be. fore George King pale and haggard—as pale and as haggerd as the body of the girl in the beliry. Mr. Barnes has :lrumed to be fair to the defendant. In conelusion, I can truly say thatin opening the case for the'people I have endeavored to the best of my ability to state without exag- geration and 10 thelx proper. Ghranology ihe facts upon which the State relied to prove beyond reasonable doubt the guilt of Theodore Durrant. 1strove to perform this most respon- sible task fully, fairly, and without prejudice or passion, official or personal. My obligation as & prosecutor required of me such an effort, and Plelieve that 1 have hing more nor less than my duty as God bhas given me the power to discern it. Imey add tnat so far as my personal feelings are concerned, 1 have struggled, not without difficulty, all through this investigation, to be more than iair to the defendant. Guilt a necessary and incvitable conclusion. 1 have tried to lay aside for the moment my sentiments of utter horror and detestation of the man of whose guilt the proofs absolutely convinced my judgment; sentiments which have daily more and more opy d and hin- dered me as in noother criminal case in which I have heretofore perticipa On the other pand, I may say that nothing been or is ain by or on behalf of the e whi has not been and is not now completely esta lished by competent evidence, Link 1 the unbroken chain has n providential welded. Step by step you have siowly, but surely advanced to the necessary and inevi- table conclusion and conviction beyond all reasonable doubt, that Theodore Durrant was the willful murdérer of Bianche Lamont; that on Wednesday afternoon, April 3, 1895, he e her life by means of strangulation in the Em- manuel Baptist Church. Mr. Barnes feels he has done his jull duty. 1f, by your solemn verdict, he shall be pro- i guilty of this feariul crime I shail v in every tiber and particle of mind and fence, official and individual, thatitis in a true verdict, weil rendered by e 3 has faithfully discharged the obli- gations 1t is under to the law, and to the munity that anxiously waits to hear its an- nouncement. 1If, on the other hand, vou shall be induced to pronounce him guiltiess I shull equally be assured that the responsibility of so dreadiul & miscarriage of justice does not rest upon my shoulders, and Will not rise to re- proach me in the time to come. This borrible d. ha; « FIT, FABRIC AND FINISH.” Who rare America’s Ready-to-Wear Clothes? Rogers, Peet & Co, and Brokaw Bros. of New York. Have they any competition? Yes—Two-edged. They compete with “ready-made’’ clothiers on price; with the swell made-to-order tailors on fit, fabric and finish. How do their goods differ from those of other clothiers? As day and night. How much difference between prices and those of 8. F. tailors? Fully one-third. ‘Where are those goods sold ? On the fourth floor, ROOS BROS. Full Dr Si finest tailors of their s Suits, Prince gle and Double Overcoats, Ulsters. All the hatters’ shapes and qualities away below the hatters’ prices. Roos Bros. 27-37 Kearny St. Champions on Mail Orders. The powers that e are the powers of Hudyan, A purely vegetable preparation, it stops all losses, cures Prematureness, LOST MANHOOD, Consti- ation, Dizziness, Falling Sensations, Nervous ‘witching of the Eyes and other parts. Strengthens, invigorates and tones tne entiro system. It is as cheap as any other remedy. HUDYAN cures Debility, Nervousness, Emis- sions and develops and restores weak Organs: pains in the back, losses by day or night stopped quickly. Over 2000 private indorsements. Prematureness means impotency in the first stage. It isasymptom of seminal weakne barrenness. It can be stopped in twenty days by the use of Hudyan. Hudyan costs no more than er remedy. 2 Blood diseases can be cured. Don't you goto hot springs before you Tead our *Blood Book.” Send for this book. 1t is free. HUDSON MEDICAL INSTITUTE, Stockton, Market and Ellis Sts., San Francisco, Cal. BROOKS’ KUMYSS cUoRES DYSPEPSIA. 119 Powell Street. BARGAINS N WALL PAPER, ROOM TTOLDINGS AND WINDOW SHADES. Large Stock of Fine Pressed Paper at Less Than Cost. Paper-hanging, Tinting and Frescoing. 811 MARKET STREET. JAMES DUFFY & CO. Dr.Gibbon’s Dispensary, G25 KEARNY 8%, Estblished in 1834 for the treatment ol Private Xhen&'& lx:t nngmdud. Debillty or 6 wearing on bodyand mind| skg;n_ Disceses The dector curesw b, otbersfail. Try him. Charges low, esgunranteed. Caliorwrite, GEBBON, Box 1957, San Francisco, NEW WESTERN HOTEL. “EARNY AND WASHINGTON STS.—RE- modeled and renavated. KING, WARD & CO, European. plan. Rooms 50¢ to $1 50 per day, 4 a&wwa&&!mlw per month; free baths; t xeo 'and €old water every T00m; fire grates in every 0 elevator runs all night. NOTARY PUBLIC. HABLES . PHILLIPS, ATTORNEY-AT W ESESANSY BILLS! - unfl"u € o