The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, August 8, 1921, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

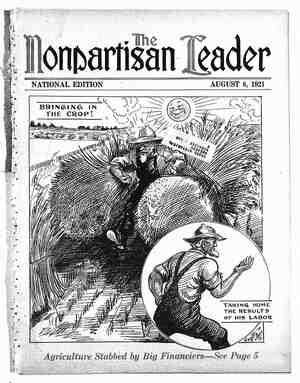

e oo S , way eked out a precarious living, pay- ° " ported them, and the financiers and _There was also the corruption of legis-" ¢ i A which to hold his erop. The latter is a matter of history and you readers will recall that the various farmer organizations held a hurriedly called con- vention in Washington and called Governor Hard- ing of the federal reserve banks on the carpet, much to that gentleman’s discomfiture. Now, these are the facts about the deflation of the farmers. It may be said that grain, cotton and meat prices were too high and that in charity for the starving populations of Europe we ought to have reduced - our prices. The answer to this is that if the farmer has anything to give away he ought to have the Will the Farmer Ever Get Justice? privilege of giving it himself. He is unwilling, however, to have his products stolen from him in the name of charity. : It will also be said that deflation is necessary. Granted. But why begin on the farmer? Why didn’t the federal reserve banks begin on the steel trust and deflate the price -of steel? Why did they not deflate the railroads—squeeze out the water from ‘the stock on which the govern- ment guar®ntees dividends? Just the contrary oc- curred with the railroads. While those in control of the nation were DEFLATING the farmers, they were actually INFLATING the rai]ro‘ads by in- creasing the rates and guaranteeing rates high enough that the railroads were sure of dividends. Why did they not deflate the lumber trust, the cement trust, the paint trust and the brick trust so that people might erect buildings again? - Instead they planned a tariff to protect those industries. ‘Why did they not deflate the landlords 'and bring down the price of rent so that wages in the cities - might be lowered ? Why did not the federal reserve banks deflate themselves, and thus reduce the price of interest? The reserve banks/now print all.the money we use. (Continued on page 15) Another Installment From a Book Published 48 Years Ago Showing That Then as Now the Farmer Was Thlnklng and Organizing HE first great agrarian movement in the United States commenced soon after the Civil war and was at its first intensity in the early seventies, 48 to 50 years ago. It was a fight that began with the old Grange, or Pa- trons of Husbandry, then a radical, fighting organ- ization whose leaders were branded as crocks, in- cendiaries and seditionists. It came to a climax in the old Farmers’ Alljance, Knights of Labor and Populist party, whose victories and threat to over- turn political conditions caused the first great farmer reforms. Great progress was made by agri- culture as a result of the farmers’ movement be- ginning a few years after the Civil war and end- - ing in the early nineties, when the People’s party passed out. Six years ago, with the birth and rapid organiza- tion of the Nonpartisan league, a new farmers’ movement was started, facing the same kind of a fight, seeking relief by solid organization and participation in politics. It is interesting, therefore, in the midst of a new era of farmer awakening, to read what the old farmer leaders of 48 and 50 years ago said and did. We have before us a book pub- lished in 1873, entitled “The History of the Grange Movement, or the Farmers’ War Against Monop- olies,” written by Edward ’Winslow Martin, from which we quoted a chapter in our last issue. Writing in this book in 1873, Martin said: “Every farmer will doubtless remember the ex- pectations that were held out to him, when the rail- road on which he is principally dependent was seeking the right of way and subscriptions toward defraying the cost of its construction. How he dreamed of the days which were to come when he could send his grain cheaply and rapidly to market! “But alas, these dreams were never realized! The road once built, the rates were based upon a scale to meet the fmanclal needs of its managers, and the farmers’ interests were never considered. The road was built to make money for its stock- holders, and the farmer must pay its tolls or his crops_can not reach the market. The inducements and promises made by the corporations at the out- set were never fulfilled. * * *- “The cost of transportation eats up about one-half of the value of the products, and the farmer’s r-ofit is made small in order that the heavy freights may be paid and the large profits of the middlemen gained.” GRANT TO RAILROADS ROUSED THE FARMERS It was not rates alone, as the old book shows, that caused the farmer to center his activity against the rail- roads. The railroads were built through government grants, but run for private profit. The railroad stock gambling made millionaires, while the . toiling farmers along the rights of mg the greater part of their earnings in freight rates. The government paid for the railroads, the farmers sup- stock gamblers made ‘the profits. lators, public officials and courts by the railroads. Their free passes, favors and graft to public men, their connection with the money :power, made it possible for them to dodge taxes, charge excessive rates, obtain Last issue the Leader published a speech by S. M. Smith, a farmer and leader in farmer orgamzatlons, deliv- ered in 1873. We found the speech in an old book called “The History of the -Grange Movement, or the Farmers’ War Against Monopolies.” It showed that- the farmers’ problems 48 years ago were much the same as now—the same fight against low prices, high frelght rates, unreasonable. middle- men’s charges and profits, bad credit conditions, etec. This rare old book, by Edward Winslow Martin, published in 1873, is so interesting and throws so smuch light on the present agricultural crisis, that we have decided to give our readers another installment from -it. " The present confiscatory railroad rates and other transportation evils recall the old fight of the farmers against the railroads. The present article deals with the railroad problem as the farmers saw it in 1873. valuable privileges and dominate the political and economic Situation. The old farmer organizations, as the book shows, exposed the wildcat financing of the railroads. The following story of the organization of the Northern ‘Pacific railroad is an interesting chapter in the book: ““In 1864 congress gran‘ed a charter to the North- ern Pacific company and by this charter and subse- quent acts authorized this company to build a rail- road from Lake Superior, through the state of Min- nesota and the territories of Dakota, Montana and Idaho, and Washington to Puget sound, by the valley of the Columbia river, through Portland in The president of the New York Stock exchange announcmg the suspension of Jay Cooke & Co., the famous financial house which went bankrupt 50 years ago as a result of attempting to finance wildcat railroad promotions. The picture is a cut from the old book from which the Leader has extracted the account on this page of the farmers’ fight against the railroads in the early seventies.: DA PAGE SIX e the state of Oregon. In aid of this roa.d congress -made large grants of land, the amount now being about 50,000,000 acres. B “The charter was granted during the last year of the Civil war, and matters were too unsettled then to allow the company to commence the work at once,-and it was not until long after the close of the Rebellion that the construction of the road was fairly begun. EXPECTED GOVERNMENT AND / PEOPLE TO FURNISH CASH “It was proposed to construct this road through the most northern portion of the United States, and from Lake Superior to the Pacific, a distance of 2,000 miles. The expense of the undertaking was enormous, and the road was to be built through a section of country that was simply a wilderness. There were scarcely any settlements along its line, a great portion of which lay through the territory -of hostile Indians. Much of the region through which it was to pass was barren and unfit for set- tlement, and a large part of the proposed route lay through the sterile region of the Yellowstone. The entire route lay through the extreme northern portion of the Republic, a country which, it was popularly believed, would long rémain unsettled by reason of the severity of the climate and the in- hospitable nature of the country. The best-inform- ed men expressed grave doubts of the practicability of the scheme. They did not believe that this re- gion would be sufficiently settled to warrant the con- struction of such a railroad for many years, and they based this belief upon the fact that the region offered scarcely any inducements to settlers. - Con- sequently people regarded the road with doubt and when its bonds were offered held aloof from them. “By the terms of the company’s charter a share capital of $100,000,000 was authorized; but of this amount “only $2,000,000 was required to be sub- scribed in advance, and but $200,000 to be paid in. The last-named sum perhaps covered the prelimi- nary expenses of the scheme, such as the cost of surveys, of legislation and such other operations as were necessary for the commencement of the enter- prise. The cost of building the road was to be paid by the people, congress had given a criminally large drea of land to the company, and the proceeds of the bonds which were issued were to constitute the capital with which the road was to be built. The $200,- 000 subscribed and paid-in by the stockholders was the only contribution they seem to have expected to make to the road. » “This was a slender provision, it would seem, for a road 2,000 miles long, through an uninhabited country, without commerce at either terminus, and without an important town on its whole route. - tended that congress should build the road and put them in possession’of it. They - secured a grant of nearly 50, 000,00¢ acres of public land, and on the security of this magmficent estate they proposed to negotiate a loan of $100,000,0€0. As the estimated cost of the road was only $85,000,000 this loan would pay for the whole wark and tingencies. The land is now. worth, say $125,000,000%. or perhaps more; *That was in 1878, It is worth billions, per- ham, hOW.: | 3 ; But the projectors in- - leave a handsome surplus for con- -