The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, July 25, 1921, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

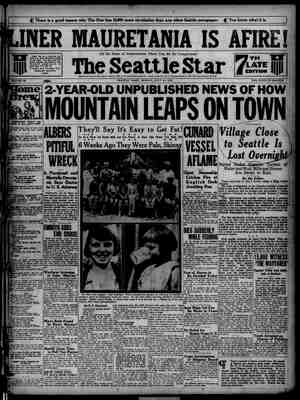

_, When Poultrymen Are Co-Operators What They Can Do for Themselves, as Proved by the Success of a Big Organization in the State of Washington BY E. A. KIRKPATRICK HERE is no magic in the word “co-op-~ eration” itself that can do anything for poultrymen, but if poultrymen in any section make up their minds to get together and STICK, no telling what they can do. The sky is the limit. At least, that is about the only conclusion I can draw from the doings of the Washington' Co- Operative Egg and Poultry association. The two branches of this association at Lynden and Belling- ham, especially, have remarkable records. This as- sociation is surpassed in size only by the much- talked-about poultrymen’s organization at Petu- lama, Cal. Whatcom county, in which Lynden and Belling- ham branches are located, is, to tegin with, a strong poultry section, and in addition the poultrymen are, almost to a man, enrolled in the association’s mem- bership. These men sell their eggs, fatten and market their fowls, and buy their feed and supplies co-operatively, with no more wrangle than a board of deacons sitting down to a pastor’s reception dinner. : “ Take the Lynden branch for an ex- ample of what co-operation can do. This was started about a year ago. The headquarters were in an old store building. Now there is a 60x140 build-~ ing, and managers needs more room to handle the average of two cars of eggs a week from the 200,000 hens represented. There is a fattening sta- tion where 15,000 birds can be handled. At this station 1,000 birds are received daily, fed for 10 days, then sold on the same pooling basis as eggs. The plant has a feeding floor, a balcony for dressing and a storage room. It is located near the creamery owned by the county dairymen’s association, and a pipe carries buttermilk from the creamery to the feeding station, for mixing up mashes. CHICKEN FEED BOUGHT AT LOW WHOLESALE PRICE The feed business began when the members pooled their orders for one car of feed. Then they decided to carry a stock of feed. This led to the grinding and mixing, and now the as- sociaton does those jobs at a saving that has made this service more popu- lar than the marketing or fattening service. The members buy a sack of feed at the same rate per pound as a ton would cost. Prices ran $5 or $6 under local quotations during April. All eggs handled by the association in Whatcom county are candled, ship- ments are pooled and are shipped to favorable markets designated by the head office at Seattle, which keeps its finger on the pulse of the egg marketing situation. Thus the best markets are found for every car of eggs. “The growth of the association was very rapid " the past year, as the fact that the membership dou- bled between November 1 and December 31 shows,” says J. L. Craib, manager of the state association. “On December 31 there was 1,196 members who had signed the producers’ agreement, and between Janu- ary 1 and March 1 the association gained members at the rate of 100 per month. At present we have branch stations at Tacoms, Bellingham, Lynden and Winlock. They have not only been of great ad- . vantage to the members, but have relieved Seattle from handling a large part of the eggs which usual- ly are shipped in there. In a large number of in- stances members have received for their eggs the same price as if they had shipped to Seattle. .In this way they have not only saved transportation charges, but have also avoided breakage in trans- portation, usually amounting to a good deal. These branch houses have to some extent increased the i THE GOVERNOR GOT LEFT Y l On a recent trip to Ortonville, Minn., Governor Frazier of North Dakota was invited to accompany the above party of Nonpartisan leaguers and Equity boosters on a fishing trip. They promised the governor good sport, but he said he had heard “fish stories” before and declined. And so he wasn’t in én this catch. The party pictured, left to right, consists of E. H. Van Krevelan, A. A. Rowe, F. E. Oshorne of the Equity Co-Operative exchange, and George Brewer, Nonpartisan league lecturer. They fished in Big Stone lake, on the border be- tween Minnesota and South Dakota. Let’s have more pictures of Leader readers doing interesting things! cost of operation, but even with this additional ex- pense you will note that the operating charges per case were less than in 1919. “The net gain from operations in 1920 amounted to $9,123.32, as against $4,001.06 for 1919. In addi- tion to this gain the shipping account of the asso- ciation shows a gain of over $5,000 up to January 1, 1921. The shipping account includes all eggs that were shipped on consignment to outside mar- kets and were charged out at the price of eggs in Seattle on the date of shipment. This profit is the difference between this price and what the associa- tion actually received for them. HANDLING COST IS LOW; SHIPS HALF TOTAL PRODUCT “On January 1 the net assets of the association were over $46,000, against net assets of a little bet- ter than $13,000 for 1919. The number of cases handled in 1920 was 85,060, against 32,716 in 1919. Since January 1, 1921, we have been handling about 20,000 cases per month, and if this volume of re- ceipts is maintained throughout the year we will handle at least a quarter of a million cases of eggs. At present we are the second largest distributors of eggs in the United States and our membership only 300 less than the membership of the Poultry Producers of Central Cali- fornia, which is reported to be the largest of its kind in the United States. eggs of all grades was $16.55 per case in 1920, or just 1 cent less per case than in 1919. The members received in checks an average of $15.56 per case and this difference of 99 cents between the gross selling price and the amount remitted to the shipper is accounted for as follows: Fifty cents per case deducted for the association’s selling charges, 15 cents per case for candling, and about 85 cents for new ‘and second-hand cases supplied to the members. The actual expense was " 45.9 cents per case, which is about 2 cents less than the handling cost of 1919. Of the total sales, the per- centage of cost for handling eggs amounted to 28 per cent, or a little less than 3 cents for every dollar’s worth of eggs sold. “You will note from the *financial statement that the association derived considerable revenue froin several other departments, and it is the inten- tion of the trustees to develop the dressed poultry and the feed depart- ments to a far greater extent than in 1920. At the present time the asso- ciation is receiving about 55 per cent of the total number of eggs produced west of the mountains.” - How Concrete Storehouses Help Farmers to Success BY F. H. SWEET zgs] OT so many years ago, when I first | came to the section of Virginia where I now live, eggs were 10 cents a dozen, wagonloads of nice apples given away to anybody after being offered in vain at 15 cents a bushel, and all cuts of beef sold by the one market at a uniform price of 12% cents a pound, first come best served. I knew of large quantities of corn fed to hogs because the 20 cents offered would not pay for hauling. Wheat was almost a drug at 60-odd,cents. And all this was less than 15 years ago. Of course under such conditions, grain and other food products were indifferently cared for. Any old damp cellar or poor shed space, or a pit in the ground to be covered with straw, was good enough for apples and potatoes and turnips. As for grain, its accessibility made red-letter days for rats and mice and squirrels, while the penetrating weather mildewed hundreds of bushels of corn for ‘many a farmer. But what of it? Corn wasn’t B AR o P TR SO SR T S S e L worth anything anyhow—not enough to build good cribs or granaries: ) Now the best kind of concrete storehouses are none too good. Permanent storage structures, proof against rodents and squirrels and rain, are going up more and more everywhere. . Hand in hand with the great importance of pro- viding proper storage for grain, has come the neces- sity for more adequate and safer methods of stor- ing vegetables. Conservative estimates place the blame for the loss of one-fourth of the potato crop each year on improper storage. In some other per- ishable crops the losses are ewen greater. The cel- lar under the house has served for many years— just as the old wooden plow at one time did. Cellars near or exposed to heat are generally too dry and the ventilation in any case poor or entirely lacking. As a result many farmers are erecting separate storage for their vegetables—a storage far better than the home cellar to keep the produce in good condition through the winter and well into the spring. Among other popular designs are concrete under- PAGE SIX § . RMSARNT L |- Hip S i ground cellars with arched roofs, with a capacity of perhaps a thousand bushels. Flat roofs, if desired, are as easily constructed. Ventilation is usually afforded by a ventilator in the roof at one end and by air intakes over the door opening at the end op- posite the entrance. The fresh air is let down into the false bottom of the cellar through channels. In this way the air reaches all parts of the chamber. The intake ducts have dampers, which may be open- cd during cool nights in the fall to prevent over- heating of the cellar. During warm days in winter they may also be opened to give the needed ventila- tion. The false bottom is raised above the concrete floor, the boards so placed that there are broad spaces between. It is well known that practically all vegetables keep best under a certain and un- varying amount of moisture, onions being the prin- cipal exception. In small storage cellars or build- ings this may be obtained by wetting down the floors occasionally. No better or surer siens of our state’s growing presperity can be found than in this enlightened way of caring for the produce. = “The average gross selling price of-