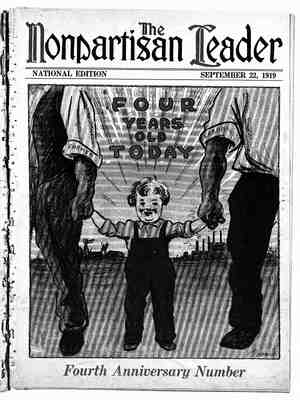

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, September 22, 1919, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Industria | Democracy in England Nationalization, Co-Operative System and Employer-Employe Councils Suggested Methods of Change Now Recognized as Needed BY PAUL FUSSELL GLAND is the most highly de- veloped industrial country in the world. Ships flying the British flag bring raw ma- terials from every continent, and return loaded with finished products manufactured in Eng- lish workshops. For genera- tions her industrial supremacy has been unquestioned, but today it is being chal- lenged by America. With our new merchant ma- rine, added to our own supply of raw materials, we are creating an industrial organization which will equal that of England. It may be well, then, to consider the present situation of labor and capital in England, for the problems which England faces today are the prob- lems which America will face tomorrow. At the outset we must recognize that the present system of industry, directed solely by capital and facing the constant threat of labor strikes, is con- demned. Labor demands a voice in the direction of its efforts; capital demands that the risk of strikes be minimized. The question of the hour is, What is to be the new industrialism? Three forms of industrial democracy have been suggested in England: The co-operative system, councils of employers and employes, and the na- tionalization of industry. First in origin and in present standing is the co-operative movement, which we have examined in detail in the earlier articles of this series. It employs more than 162,000 men and women, and has a payroll amounting to $62,000,000 a year. In each society, control is vested in a board of direc- tors responsible to the members of that society. We should not forget that the aim of the found- ers of the co-operative system, and the aim of its leaders today, is not only to enable working people to buy the necessities of life as cheaply as pos- sible, but to establish a co-operative commonwealth, where trade and industry are controlled by the vast army of consumers. Striking as the suec- cess of co-operation has been, we should not be blinded to its limitations. It is co-operation, we should remember, from the standpoint of the consumer and not of the producer. The employes have no share in the profits of the factory and no voice in its oper- ation. Their sole advan- tage lies in the fact that their employers are working people and nat- urally are in sympathy with the rights of labor. The co-operative system, from the point of view of the employe, is not in- dustrial democracy, but benevolent capitalism. The co-operative movement, also, is neces- sarily dependent for support upon the free will of- ferings of its members. The state can tax its citi- zens; the corporation can assess its shareholders; but the co-operative society can obtain new funds only from the profits of past business or from the shares of new members. Often desirable oppor- tunities to extend trade must be neglected because of the inelasticity of co-operative financing. POLITICAL NEED NOW SEEN BY CO-OPERATIVES For many years, also, co-operation has suffered because of its traditional attitude of political neu- trality. Having no friends with either party, it suffered from both. This may be illustrated by the fact that co-operative organizations, though not operated for profit, have been subjected to the same war profits taxation as corporations con- ducted only with a view to dividends. Wearied of these injustices, the co-operative leaders entered the political arena in 1918 and elected one of their leading men to the house of commons. The co-operative congress in June, 1919, ratified this action, and decided to associate itself with the Labor party in future political action. Industrial democracy, even in so limited a form as co-operation, requires the helping hand of political democracy. Hereafter British co-operation, for its own protection, will be a tremendous factor in British politics. Second in origin are the councils of employers and employes. Several years ago a government committee was appointed, officially -termed the Committee on Relations Between Employers and Employes, but unofficially termed the Whitley com- mittee. It has issued a series of five considered reports recommending industrial reform. Its chief recommendation was that joint standing industrial councils should be established, each council to rep- resent equally the employers and the employes in a given industry. These councils are to be advisory to the employers and, employes in such questions - as industrial training; utilization of inventions and industrial research; and advisory to the govern- ment in all questions affecting industrial legisla- tion. They give employes an opportunity to make suggestions and to meet their employers on an equal basis. : Today there are 16 joint industrial councils in operation in 16 of the most highly developed in- dustries. In addition, a national industrial con- ference was held on February 27, 1919, with 800 delegates representing capital and labor in all in- dustries. This conference, too large to work well, appointed a joint committee of 30 employers and 30 employes. After a month’s consideration this committee published a unanimous report, recom- mending a maximum week of 48 hours; minimum time rates of wages to be set by a joint commis- sion; adequate provision for maintenance during unemployment, and the immediate creation of a permanent industrial council of 400 members, with a standing committee of 50 members, represent- ing capital and labor equally, to be recognized by the government as the official consultative I SHOW PLACES OF LONDON I *LONDON - THAFALG AR SQUARE. Above—Buckingham palace, official residence of the British royal family. Despite the pomp that surrounds the king, he has practically no real power. authority in industrial disputes in Great Britain. On May 4, after a week’s study of the report, Lloyd George stated: “Foreign countries are look- ing to Great Britain to give them a lead in the foundation of a newer and better industrialism, and this report marks the beginning of such a foun- dation.” In detail, he agreed to the fixing of maxi- mum hours and minimum wages and the creation of a national council. The program unanimously adopted by capital and labor became a part of the program of the British government. MANY LEADERS OPPOSE JOINT COUNCIL PLAN The industrial councils, like’ the co-operative system, have their limitations. They may only recommend. Labor can not be sure that capital will follow its advice if it urges shorter hours; capital can not tell whether labor will comply if the' council recommends against a strike; and neither can be sure that the government will enact the legislation desired. Creation of these joint industrial councils is opposed by many labor lead- ers. They see in it an attempt to patch up the system of industry for private profits which is, in their opinion, beyond repair. Their solution is neither co-operation nor joint councils, but nation- alization. Their means is neither business nor ad- vice, but immediate political action. Nationalization of industry is the third proposal for industrial democracy. By nationalization is meant state ownership, with control exercised jointly by the state, the managers and the em- ployes. So far it has been proposed only for cer- tain industries which materially affect the public interest—mines, railroads and shipping. In March, 1919, Great Britain faced a severe in- dustrial crisis. More than 1,000,000 men, many of them ex-soldiers, were out of work, drawing week- ly unemployment pay. The Triple alliance, a league of the three strongest trades unions, the miners, railway workers and transport workers, was on the point of calling a national strike of its 2,500,- 000 members. England, faced industrial paralysis. At this troubled time, the coal industry commis- sion issued a report which cleared the air. This commission consisted of three representatives of capital, three of labor and six of the government. It recommended, not merely an increase in wages and a decrease in hours, but a reorgani- zation of the industry itself. “Upon the evi- dence already given,” declared the report, “the present system of ownership and working in the coal industry stands condemned, and some other system must be substituted for it.” The commission continues with the statement that the time at its disposal did not allow it to make recommendations on the subject of nationaliza- tion, and it added: “We are prepared, how- ever, to report now that it is in the interests of the country that the colliery worker shall in the future have an effective voice in the di- « rection of the mine.” The recommendations of the commission as re- gards hours and wages were adopted by the government as the basis of settling the threaten- ed strike, and the com- missibn was ~ continued for a further study of the subject of nationali- zation. Briefly stated, the pro- posal for the nationali- zation of mining is as follows: The prime min- ister shall appoint a minister of mines who shall be a member of the cabinet. This minister is to be chairman of a mining council of 10 members, five to be ap- pointed by the miners’ federation, and five to be Little by little this power has been taken from the kings of Great Britain, - appointed by the state, until now it is almost all lodged in the house of commons, elected by the people of the islands. Below—Trafalgar square, with the Lord Nelson monument. is named after the famous battle in which England’s foremost naval hero won his greatest victory and died. The monument, too, was erected in his honor. PAGE EIGHT three to represent mine owners and two to rep- resent consumers. This council 'is to buy at a (Continued on page 15) The square eip